User:Gravislizard/sandbox

A modem – a portmanteau of "modulator-demodulator" – is a hardware device that converts data from a digital format, intended for communication directly between devices with specialized wiring, into one suitable for a transmission medium such as telephone lines or radio. A modem modulates one or more carrier wave signals to encode digital information for transmission, and demodulates signals to decode the transmitted information. The goal is to produce a signal that can be transmitted easily and decoded reliably to reproduce the original digital data.

Modems can be used with almost any means of transmitting analog signals, from light-emitting diodes to radio. A common type of modem is one that turns the digital data of a computer into a modulated electrical signal for transmission over telephone lines, to be demodulated by another modem at the receiver side to recover the digital data.

Speeds

[edit]Modems are frequently classified by the maximum amount of data they can send in a given unit of time, usually expressed in bits per second (symbol bit/s, sometimes abbreviated "bps") or rarely in bytes per second (symbol B/s). Modern broadband modems are typically described in megabits.

Historically, modems were often classified by their symbol rate, measured in baud. The baud unit denotes symbols per second, or the number of times per second the modem sends a new signal. For example, the ITU V.21 standard used audio frequency-shift keying with two possible frequencies, corresponding to two distinct symbols (or one bit per symbol), to carry 300 bits per second using 300 baud. By contrast, the original ITU V.22 standard, which could transmit and receive four distinct symbols (two bits per symbol), transmitted 1,200 bits by sending 600 symbols per second (600 baud) using phase-shift keying.

Many modems are variable-rate, permitting them to be used over a medium with less than ideal characteristics, such as a telephone line that is of poor quality or is too long. This capability is often adaptive so that a modem can discover the maximum practical transmission rate during the connect phase, or during operation.

Overall history

[edit]Modems grew out of the need to connect teleprinters over ordinary phone lines instead of the more expensive leased lines which had previously been used for current loop–based teleprinters and automated telegraphs. The earliest devices that satisfy the definition of a modem may be the multiplexers used by news wire services in the 1920s.[1]

In 1941, the Allies developed a voice encryption system called SIGSALY which used a vocoder to digitize speech, then encrypted the speech with one-time pad and encoded the digital data as tones using frequency shift keying. This was also a digital modulation technique.[2]

Commercial modems largely did not become available until the late 1950s, when the rapid development of computer technology created demand for a method of connecting computers together over long distances, resulting in the Bell Company and then other businesses producing an increasing number of computer modems for use over both switched and leased telephone lines.

Later developments would produce modems that operated over cable television lines, power lines, and various radio technologies, as well as modems that achieved much higher speeds over telephone lines.

Dial-up modem

[edit]A dial-up modem transmits computer data over an ordinary switched telephone line that has not been designed for data use. This contrasts with leased line modems, which also operate over lines provided by a telephone company, but ones which are intended for data use and do not impose the same signaling constraints.

The modulated data must fit the frequency constraints of a normal voice audio signal, and the modem must be able to perform the actions needed to connect a call through a telephone exchange, namely: picking up the line, dialing, understanding signals sent back by phone company equipment (dialtone, ringing, busy signal,) and on the far end of the call, the second modem in the connection must be able to recognize the incoming ring signal and answer the line.

Dial-up modems have been made in a wide variety of speeds and capabilities, with many capable of testing the line they're calling over and selecting the most advanced signaling mode that the line can support. Generally speaking, the fastest dialup modems ever available to consumers never exceeded 56 KiB/s, and never achieved that speed in both directions.

The dial-up modem was once a widely known technology, since it was mass-marketed to consumers in many countries for dial-up internet access. In the 90s, tens of millions of people in the United States used dial-up modems for internet access.[3]

Dial-up service has since been largely supplanted by broadband internet[4], which typically still uses a modem, but of a very different type which may still operate over a normal phone line, but with substantially relaxed constraints.

Dial modem history

[edit]

Mass production of telephone line modems in the United States began as part of the SAGE air-defense system in 1958 (the year the word modem was first used[5]), connecting terminals at various airbases, radar sites, and command-and-control centers to the SAGE director centers scattered around the United States and Canada.

Shortly afterwards in 1959, the technology in the SAGE modems was made available commercially as the Bell 101, which provided 110 bit/s speeds. Bell called this and several other early modems "datasets."

The Bell 103A standard was introduced by AT&T in 1962. It provided full-duplex service at 300 bit/s over normal phone lines. Frequency-shift keying was used, with the call originator transmitting at 1,070 or 1,270 Hz and the answering modem transmitting at 2,025 or 2,225 Hz.[6] The 103 modem would eventually become a de facto standard once third-party (non-AT&T modems) reached the market.

The 103A2 gave an important boost to the use of remote low-speed terminals such as the Teletype Model 33 ASR and KSR, and the IBM 2741. AT&T also produced reduced-cost units, the originate-only 113D and the answer-only 113B/C modems.

The 201A and 201B Data-Phones were synchronous modems using two-bit-per-baud phase-shift keying (PSK). The 201A operated half-duplex at 2,000 bit/s over normal phone lines, while the 201B provided full duplex 2,400 bit/s service on four-wire leased lines, the send and receive channels each running on their own set of two wires.

Throughout the 1970s, acoustically coupled modems compatible with the Bell 103A de-facto standard were commonplace. Well-known models included the Novation CAT and the Anderson-Jacobson. A lower-cost option was the Pennywhistle modem, designed to be built using parts from electronics scrap and surplus stores.

In December 1972, Vadic introduced the VA3400, notable for full-duplex operation at 1,200 bit/s over the phone network. Like the 103A, it used different frequency bands for transmit and receive.

In November 1976, AT&T introduced the 212A modem to compete with Vadic. It was similar in design, but used the lower frequency set for transmission. One could also use the 212A with a 103A modem at 300 bit/s. According to Vadic, the change in frequency assignments made the 212 intentionally incompatible with acoustic coupling, thereby locking out many potential modem manufacturers.

In 1977, Vadic responded with the VA3467 triple modem, an answer-only modem sold to computer center operators that supported Vadic's 1,200-bit/s mode, AT&T's 212A mode, and 103A operation.

The Hayes Smartmodem

[edit]

The next major advance in modems was the Hayes Smartmodem, introduced in 1981. The Smartmodem was an otherwise standard 103A 300 bit/s direct-connect modem, but it included a microcontroller that watched the data stream for certain character strings representing commands, which it used to control functions like dialing and answering.

The Hayes command set used by this device became a de-facto standard supported by devices from many other manufacturers. It included instructions for picking up and hanging up the line, dialing and answering calls, among others. This was similar to the commands offered by internal modems, but unlike those, the Smartmodem could be connected to any computer with an RS-232 port, which was practically every microcomputer built.

The introduction of the Smartmodem made communications much simpler and more easily accessed. This provided a growing market for other vendors, who licensed the Hayes patents and competed on price or by adding features.

Standards

[edit]Modems must share common standards in order to communicate. Since many dial-up modem standards have been developed over the decades, it is important to know which standards are supported by a given modem. Some modems support multiple standards, with more recent models often having extensive backwards compatibility. Most modern modems will perform a complex handshake procedure to discover the best communication standard that is both supported by the devices on both ends of the connection, and possible given current line conditions.

Early standards

[edit]Frequency-shift keying

[edit]From 1958-1963, Bell produced several standards utilizing frequency-shift keying, achieving speeds of 110-1200 bit/s.

FSK utilizes a pair of set frequencies to represent digital values. In the Bell 103 system for instance, the originating modem sends 0s by playing a 1,070 Hz tone, and 1s at 1,270 Hz. To prevent interference, the answering modem transmits its 0s on 2,025 Hz and 1s on 2,225 Hz. These frequencies were chosen carefully; they are in the range that suffers minimum distortion on the phone system, and are not harmonics of each other.

| Model | Introduced | Baudrate | Speed | Encoding | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bell 101 | 1958 | 110 bit/s | FSK | ||

| Bell 103 | 1963 | 300 bit/s | FSK | ITU-T V.21 is a similar but incompatible standard | |

| Bell 202 | 1976 | 1200 bit/s | FSK | To achieve 1200 bit/s with plain FSK, the Bell 202 can only achieve this speed in one direction at a time. |

Phase-shift keying & QAM

[edit]To achieve higher speeds than the early FSK standards, new encodings were adopted. Phase-shift keying still used two tones for any one side of the connection, but transmitted with slightly different phases. QAM used a pair of carriers modulated with amplitude-shift keying to achieve higher bitrates at the same symbol rate.

| Model | Baudrate | Speed | Encoding | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| v.21 | 1988 | 110 bit/s | FSK | ||

| v.22 | 300 bit/s | FSK | ITU-T V.21 is a similar but incompatible standard | ||

| v.22bis | 1200 bit/s | FSK | To achieve 1200 bit/s with plain FSK, the Bell 202 can only achieve this speed in one direction at a time. |

V.22 600 baud - 600 / 1200 bit/s

V.22bis QAM, 600 baud, 2400 bit/s

A V.22bis 2,400-bit/s system similar in concept to the 1,200-bit/s Bell 212 signaling was introduced in the U.S., and a slightly different one in Europe.

The use of smaller shifts had the drawback of making each symbol more vulnerable to interference, but improvements in phone line quality at around the same time helped compensate for this. By the late 1980s, most modems could support all of these standards and 2,400-bit/s operation was becoming common.

Impact on computer networking

[edit]Throughout the 1980s, increasing modem speed greatly improved the responsiveness of online systems, and made file transfer practical. This led to rapid growth of online services with large file libraries, which in turn gave more reason to own a modem. The rapid update of modems led to a similar rapid increase in BBS use.

The introduction of microcomputer systems with internal expansion slots made the first software-controllable modems common. Slot connections gave the computer complete access to the modem's memory or input/output (I/O) channels, which allowed software to send commands to the modem, not just data. This led to a series of popular modems for the S-100 bus and Apple II computers that could directly dial the phone, answer incoming calls, and hang up the phone, the basic requirements of a bulletin board system (BBS). The seminal CBBS for instance was created on an S-100 machine with a Hayes internal modem, and a number of similar systems followed.

Proprietary standards

[edit]Many other standards were also introduced for special purposes, commonly using a high-speed channel for receiving, and a lower-speed channel for sending. One typical example was used in the French Minitel system, in which the user's terminals spent the majority of their time receiving information. The modem in the Minitel terminal thus operated at 1,200 bit/s for reception, and 75 bit/s for sending commands back to the servers.

Three U.S. companies became famous for high-speed versions of the same concept. Telebit introduced its Trailblazer modem in 1984, which used a large number of 36 bit/s channels to send data one-way at rates up to 18,432 bit/s. A single additional channel in the reverse direction allowed the two modems to communicate how much data was waiting at either end of the link, and the modems could change direction on the fly. The Trailblazer modems also supported a feature that allowed them to spoof the UUCP g protocol, commonly used on Unix systems to send e-mail, and thereby speed UUCP up by a tremendous amount. Trailblazers thus became extremely common on Unix systems, and maintained their dominance in this market well into the 1990s.

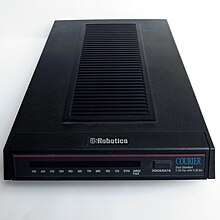

USRobotics (USR) introduced a similar system, known as HST, although this supplied only 9,600 bit/s (in the early versions) and provided for a larger backchannel. Rather than offer spoofing, USR instead created a large market among FidoNet users by offering its modems to BBS sysops at a much lower price, resulting in sales to end users who wanted faster file transfers. Hayes was forced to compete, and introduced its own 9,600 bit/s standard, Express 96 (also known as Ping-Pong), which was generally similar to Telebit's PEP. Hayes, however, offered neither protocol spoofing nor sysop discounts, and its high-speed modems remained rare.

A common feature of these high-speed modems was the concept of fallback, or speed hunting, allowing them to communicate with less-capable modems. During the call initiation, the modem would transmit a series of signals and wait for the remote modem to respond. They would start with standards supporting high speeds and progressively fall back to slower standards until there was a response. Thus, two USR modems would be able to connect at 9,600 bit/s, but, when a user with a 2,400 bit/s modem called in, the USR would fall back to the common 2,400 bit/s speed. This would also happen if a V.32 modem and a HST modem were connected. Because they used a different standard at 9,600 bit/s, they would fall back to their highest commonly supported standard at 2,400 bit/s. The same applies to V.32bis and 14,400 bit/s HST modem, which would still be able to communicate with each other at 2,400 bit/s.

Echo cancellation - 9,600 bit/s

[edit]

Echo cancellation was the next major advance in modem design.

Local telephone lines use the same wires to send and receive data, which results in a small amount of the outgoing signal being reflected back. This is useful for people talking on the phone, as it provides a signal to the speaker that their voice is making it through the system. However, this reflected signal causes problems for a modem, which is unable to distinguish between a signal from the remote modem and the echo of its own signal.

For this reason, earlier modems split the signal frequencies, so that the devices on either end used different tones, allowing each one to ignore any signals in the frequency range it was using for transmission. Even with improvements to the phone system allowing higher speeds, this splitting of available phone signal bandwidth still imposed limits on modems.

Echo cancellation eliminated this problem. During the call setup and negotiation period, both modems send a series of unique tones and then listen for them to return through the phone system. They measure the total delay time and then set up a local delay loop to the same time. Once the connection is completed, they send their signals into the phone lines as normal, but also into a delay line. When their signal is reflected back, it is mixed with the inverted signal from the delay line, which cancels out the echo. This allowed both modems to use the full spectrum available, doubling the possible speed.

Additional improvements were introduced via the quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM) encoding system. Previous systems using phase shift keying (PSK) encoded two bits (or sometimes three) per symbol by slightly delaying or advancing the signal's phase relative to a set carrier tone. QAM used a combination of phase shift and amplitude to encode four bits per symbol.

Transmitting at 1,200 baud produced the 4,800 bit/s V.27ter standard, and at 2,400 baud the 9,600 bit/s V.32. The carrier frequency was 1,650 Hz in both systems. For many years, most engineers considered this rate to be the limit of data communications over telephone networks.

The introduction of these higher-speed systems also led to the development of the digital fax machine during the 1980s. While early fax technology also used modulated signals on a phone line, digital fax used the now-standard digital encoding used by computer modems. This eventually allowed computers to send and receive fax images.

Breaking the 9,600 bit/s barrier

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

The first 9,600 bit/s modem was developed in 1968, and sold for more than $20,000, but had high error rates.[7]

In 1980, Gottfried Ungerboeck from IBM Zurich Research Laboratory applied channel coding techniques to search for new ways to increase the speed of modems. His results were astonishing but only conveyed to a few colleagues.[8] In 1982, he agreed to publish what is now a landmark paper in the theory of information coding.[9] By applying parity check coding to the bits in each symbol, and mapping the encoded bits into a two-dimensional diamond pattern, Ungerboeck showed that it was possible to increase the speed by a factor of two with the same error rate. The new technique was called mapping by set partitions, now known as trellis modulation.

Error correcting codes, which encode code words (sets of bits) in such a way that they are far from each other, so that in case of error they are still closest to the original word (and not confused with another) can be thought of as analogous to sphere packing or packing pennies on a surface: the further two bit sequences are from one another, the easier it is to correct minor errors.

Dave Forney introduced the trellis diagram in a landmark 1973 paper that popularized the Viterbi algorithm.[7] Practically all modems operating faster than 9600 bit/s decode trellis-modulated data using the Viterbi algorithm.

V.32 modems operating at 9600 bit/s were expensive and were only starting to enter the market in the early 1990s when V.32bis was standardized. Rockwell International's chip division developed a new driver chip set incorporating the standard and aggressively priced it. Supra, Inc. arranged a short-term exclusivity arrangement with Rockwell, and developed the SupraFAXModem 14400 based on it. Introduced in January 1992 at $399 (or less), it was half the price of the slower V.32 modems already on the market. This led to a price war, and by the end of the year V.32 was dead, never having been really established, and V.32bis modems were widely available for $250.

V.32bis was so successful that the older high-speed standards had little to recommend them. USR fought back with a 16,800 bit/s version of HST, while AT&T introduced a one-off 19,200 bit/s method they referred to as V.32ter, but neither non-standard modem sold well.

On-the-fly compression

[edit]V.42, V.42bis and V.44 standards allow the modem to transmit data faster than its basic rate would imply. For instance, a 53.3 kbit/s connection with V.44 can transmit up to 53.3 × 6 = 320 kbit/s using pure text. However, the compression ratio varies based on the transmitted data, for instance the transfer of already-compressed files (ZIP files, JPEG images, MP3 audio, MPEG video) leads to negligible on-line compression.[10] When using an on-line compression standard, the data rate varies during operation, compressed files might be sent at approximately 50 kbit/s, uncompressed files at 160 kbit/s, and pure text at 320 kbit/s.[11]

In such situations, a small amount of memory in the modem, a buffer, is used to hold the data while it is being compressed and sent across the phone line, but in order to prevent overflow of the buffer, it sometimes becomes necessary to tell the computer to pause the datastream. This is accomplished through hardware flow control using extra lines on the modem–computer connection. The computer is then set to supply the modem at some higher rate, such as 320 kbit/s, and the modem will tell the computer when to start or stop sending data.

V.34/28.8 kbit/s and 33.6 kbit/s

[edit]

Consumer interest in these proprietary improvements waned during the lengthy introduction of the 28,800 bit/s V.34 standard. While waiting, several companies decided to release hardware and introduced modems they referred to as V.FAST.

In order to guarantee compatibility with V.34 modems once the standard was ratified (1994), manufacturers used more flexible components, generally a DSP and microcontroller, as opposed to purpose-designed ASIC modem chips. This would allow later firmware updates to conform with the standards once ratified.

The ITU standard V.34 represents the culmination of these joint efforts. It employs the most powerful coding techniques available at the time, including channel encoding and shape encoding. From the mere four bits per symbol (9.6 kbit/s), the new standards used the functional equivalent of 6 to 10 bits per symbol, plus increasing baud rates from 2,400 to 3,429, to create 14.4, 28.8, and 33.6 kbit/s modems. This rate is near the theoretical Shannon limit.

When calculated, the Shannon capacity of a narrowband line is , with the (linear) signal-to-noise ratio. Narrowband phone lines have a bandwidth of 3,000 Hz so using (SNR = 30 dB), the capacity is approximately 30 kbit/s.[12]

56kbit/s technologies

[edit]While 56,000 bit/s speeds had been available for leased-line modems for some time, they did not become available for dial modems until the 90s.

In the late 1990s, technologies to achieve speeds above 33.6kbit/s began to be introduced, colloquially referred to as 56k. Several approaches were used, but all of them began as solutions to a single fundamental problem with phone lines.

By the time technology companies began to investigate speeds above 33.6kbit/s, telephone companies had switched almost entirely to all-digital networks. As soon as a phone line reached a local central office, a line card converted the analog signal from the subscriber to a digital one, and vice versa. While digitally encoded telephone lines notionally provide the same bandwidth as the analog systems they replaced, the digitization itself placed constraints on the types of waveforms that could be reliably encoded.

The first problem was that the process of analog-to-digital conversion is intrinsically lossy, but second, and more importantly, the digital signals used by the telcos were not "linear" - they did not encode all frequencies the same way, instead utilizing a nonlinear encoding (μ-law and a-law) meant to favor the nonlinear response of the human ear to voice signals. This made it very difficult to find a 56kbit/s encoding that could survive the digitizing process.

Modem manufacturers discovered that, while the analog to digital conversion could not preserve higher speeds, digital to analog conversions could. Because it was possible for an ISP to obtain a direct digital connection to a telco, a digital modem - one that connects directly to a digital telephone network interface, such as T1 or PRI - could send a signal that utilized every bit of bandwidth available in the system. While that signal still had to be converted back to analog at the subscriber end, that conversion would not distort the signal in the same way that the opposite direction did.

For this same reason, while 56k did permit 56kbit/s downstream (from ISP to subscriber), the same speed was never achieved in the upstream (from the subscriber to the ISP) direction, because that required going through an analog-to-digital conversion. This problem was never overcome.[13]

Early 56k dial-up products

[edit]The first 56k dial-up option was a proprietary design from USRobotics, which they called "X2," because 56k was twice the speed (x2) of 28k modems.

At that time, USRobotics held a 40-percent share of the retail modem market, while Rockwell International held an 80-percent share of the modem chipset market. Concerned with being shut out, Rockwell began work on a rival 56k technology. They joined with Lucent and Motorola to develop what they called "K56Flex" or just "Flex."

Both technologies reached the market around February 1997; although problems with K56Flex modems were noted in product reviews through July, within six months the two technologies worked equally well, with variations dependent largely on local connection characteristics.[14]

The retail price of these early 56K modems was about US$200, compared to $100 for standard 33k modems. Compatible equipment was also required at the Internet service providers (ISPs) end, with costs varying depending on whether their current equipment could be upgraded. About half of all ISPs offered 56k support by October 1997. Consumer sales were relatively low, which USRobotics and Rockwell attributed to conflicting standards.[15]

Standardized 56k (V.90/V.92)

[edit]In February 1998, The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) announced the draft of a new 56 kbit/s standard, V.90, with strong industry support. Incompatible with either existing standard, it was an amalgam of both, but was designed to allow both types of modem to by a firmware upgrade. The V.90 standard was approved in September 1998, and widely adopted by ISPs and consumers.[15][16]

The V.92 standard was approved by ITU in November 2000[17], and utilized digital PCM technology to increase the upload speed to a maximum of 48 kbit/s.

The high upload speed was a tradeoff. 48 kbit/s upstream rate would reduce the downstream as low as 40 kbit/s due to echo effects on the line. To avoid this problem, V.92 modems offer the option to turn off the digital upstream and instead use a plain 33.6 kbit/s analog connection in order to maintain a high digital downstream of 50 kbit/s or higher.[18]

V.92 also added two other features. The first is the ability for users who have call waiting to put their dial-up Internet connection on hold for extended periods of time while they answer a call. The second feature is the ability to quickly connect to one's ISP, achieved by remembering the analog and digital characteristics of the telephone line, and using this saved information when reconnecting.

ISP compression

[edit]As telephone-based 56k modems began losing popularity, some Internet service providers such as Netzero/Juno, Netscape, and others started using pre-compression to increase the throughput and maintain their customer base. The server-side compression operates much more efficiently than the on-the-fly compression done by modems because these compression techniques are application-specific (JPEG, text, EXE, etc.). Website text, images, and Flash media are typically compacted to approximately 4%, 12%, and 30%, respectively. The drawback of this approach is a loss in quality, which causes image content to become pixelated and smeared. ISPs employing this approach often advertise it as "accelerated dial-up".

These accelerated downloads are now integrated into the Opera and Amazon Silk web browsers, using their own server-side text and image compression.

Methods of attachment

[edit]Dial-up modems can attach in two different ways: with an acoustic coupler, or with a direct electrical connection.

Acoustic couplers

[edit]

While Bell (AT&T) provided modems that attached via direct wire connection to the phone network as early as 1958, their regulations at that time did not permit the direct electrical connection of any non-Bell device to a telephone line. However, the Hush-a-Phone ruling allowed customers to attach any device to a telephone set as long as it did not interfere with its functionality. This allowed third-party (non-Bell) manufacturers to sell modems utilizing an acoustic coupler.[19]

With an acoustic coupler, an ordinary telephone handset was placed in a cradle containing a speaker and microphone positioned to match up with those on the handset. The tones used by the modem were transmitted and received into the handset, which then relayed them to the phone line.[20]

Because the modem was not electrically connected, it was incapable of picking up, hanging up or dialing, all of which required direct control of the line. Touch-tone dialing would have been possible, but touch-tone was not universally available at this time. Consequently, the dialing process was executed by the user lifting the handset, dialing, then placing the handset on the coupler.

Directly connected modems

[edit]This section is missing information about DAA. (August 2020) |

The Hush-a-Phone decision which legalized acoustic couplers applied only to mechanical connections to a telephone set, not electrical connections to the telephone line. The Carterfone decision of 1968, however, permitted customers to attach devices directly to a telephone line as long as they followed stringent Bell-defined standards for non-interference with the phone network.[19] This opened the door to direct-connect modems that plugged directly into the phone line rather than via a coupler, which eventually became ubiquitous.

The rapidly falling prices of electronics in the late 1970s led to an increasing number of direct-connect models around 1980. In spite of being directly connected, these modems were generally operated like their earlier acoustic versions – dialing and other phone-control operations were completed by hand, using an attached handset. A small number of modems added the ability to automatically answer incoming calls, or automatically place an outgoing call to a single number, but even these limited features were relatively rare or limited to special models in a lineup.

When more flexible solutions were needed, third party "dialers" were used to automate calling, normally using a separate serial port to communicate with the dialer, which would then control the modem through a private electrical connection.

Controller-based modems vs. Softmodems/Winmodems

[edit]

Traditionally, modems contain all the electronics and intelligence to convert data from bytes to an analog signal and back again, and to handle the dialing process. These are sometimes referred to as "Controller-based modems."[21] Virtually any modem with a serial connection is controller-based; since the only thing it can receive from the host computer is the bytes of the data stream, it has to handle everything else.

A softmodem is a stripped-down variant that replaces tasks traditionally handled in hardware with software. These can be thought of as little more than a PC sound card with a telephone line-compatible interface. The audio sent and received on the line is generated and processed by software in a device driver running in the PC's operating system. There is little functional difference from the user's perspective, but this design reduces the cost of a modem by moving most of the processing into inexpensive software instead of expensive hardware DSPs and microcontrollers.

Softmodems do not use an RS-232 interface to the host PC because they need to be able to exchange audio data with the PC directly. Instead, they connect over internal buses such as ISA, PCI or PCI Express, or external buses such as USB.

Since the interface is not RS-232, there is no standard for communication with the device directly. Instead, softmodems come with drivers which create a virtual RS-232 port which standard modem software (such as an operating system dialer application) can communicate with, but these drivers are frequently designed only for Windows, with Mac and Linux supported less commonly. The only way to make softmodems work on these platforms is to reverse-engineer their drivers. This has led to these devices sometimes being called Winmodems, to highlight their Windows-only functionality.

Evolution of dial-up speeds

[edit]These values are maximum values, and actual values may be slower under certain conditions (for example, noisy phone lines).[22] For a complete list see the companion article list of device bandwidths. A baud is one symbol per second; each symbol may encode one or more data bits.

|

|

| Connection | Modulation | Bitrate [kbit/s] | Year released |

|---|---|---|---|

| 110 baud Bell 101 modem | FSK | 0.1 | 1958 |

| 300 baud (Bell 103 or V.21) | FSK | 0.3 | 1962 |

| 1200 modem (1200 baud) (Bell 202) | FSK | 1.2 | 1976 |

| 1200 modem (600 baud) (Bell 212A or V.22) | QPSK | 1.2 | 1980[23][24] |

| 2400 modem (600 baud) (V.22bis) | QAM | 2.4 | 1984[23] |

| 2400 modem (1200 baud) (V.26bis) | PSK | 2.4 | |

| 4800 modem (1600 baud) (V.27ter) | PSK | 4.8 | [25] |

| 9600 modem (2400 baud) (V.32) | QAM | 9.6 | 1984[23] |

| 14.4k modem (2400 baud) (V.32bis) | trellis | 14.4 | 1991[23] |

| 19.2k modem (2400 baud) (V.32 "terbo") | trellis | 19.2 | 1993[23] |

| 28.8k modem (3200 baud) (V.34) | trellis | 28.8 | 1994[23] |

| 33.6k modem (3429 baud) (V.34) | trellis | 33.6 | 1996[26] |

| 56k modem (8000/3429 baud) (V.90) | digital | 56.0/33.6 | 1998[23] |

| 56k modem (8000/8000 baud) (V.92) | digital | 56.0/48.0 | 2000[23] |

| Bonding modem (two 56k modems) (V.92)[27] | 112.0/96.0 | ||

| Hardware compression (variable) (V.90/V.42bis) | 56.0–220.0 | ||

| Hardware compression (variable) (V.92/V.44) | 56.0–320.0 | ||

| Server-side web compression (variable) (Netscape ISP) | 100.0–1,000.0 |

Popularity

[edit]A 1994 Software Publishers Association found that although 60% of computers in US households had a modem, only 7% of households went online.[28] A CEA study in 2006 found that dial-up Internet access was declining in the U.S. In 2000, dial-up Internet connections accounted for 74% of all U.S. residential Internet connections.[citation needed] The United States demographic pattern for dial-up modem users per capita has been more or less mirrored in Canada and Australia for the past 20 years.

Dial-up modem use in the U.S. had dropped to 60% by 2003, and in 2006, stood at 36%.[citation needed] Voiceband modems were once the most popular means of Internet access in the U.S., but with the advent of new ways of accessing the Internet, the traditional 56K modem was losing popularity. The dial-up modem is still widely used by customers in rural areas, where DSL, cable, satellite, or fiber optic service is not available, or they are unwilling to pay what these companies charge.[29] In its 2012 annual report, AOL showed it still collected around US$700 million in fees from dial-up users: about three million people.

Voice/fax modems

[edit]"Voice" and "fax" are terms added to describe any dial modem that is capable of recording/playing audio or transmitting/receiving faxes. Some modems are capable of all three functions.[30]

Voice modems are used for computer telephony integration applications as simple as placing/receiving calls directly through a computer with a headset, and as complex as fully automated robocalling systems.

Fax modems can be used for computer-based faxing, in which faxes are sent and received without inbound or outbound faxes ever needing to ever be printed on paper. This differs from efax, in which faxing occurs over the internet, in some cases involving no phone lines whatsoever.

Leased-Line Modem

[edit]A leased line modem also uses ordinary phone wiring, like dial-up and DSL, but does not use the same network topology. While dial-up uses a normal phone line and connects through the telephone switching system, and DSL uses a normal phone line but connects to equipment at the telco central office, leased lines do not terminate at the telco.

Leased lines are pairs of telephone wire that have been connected together at one or more telco central offices so that they form a continuous circuit between two subscriber locations, such as a business' headquarters and a satellite office. They provide no power or dialtone - they are simply a pair of wires connected at two distant locations.

A dialup modem will not function across this type of line, because it does not provide the power, dialtone and switching that those modems require. However, a modem with leased-line capability can operate over such a line, and in fact can have greater performance because the line is not passing through the telco switching equipment, the signal is not filtered, and therefore higher analog bandwidth is available.

Leased-line modems can operate in 2-wire or 4-wire mode. The former uses a single pair of wires and can only transmit in one direction at a time, while the latter uses two pairs of wires and can transmit in both directions simultaneously. When two pairs are available, bandwidth can be as high as 1.5mbps, a full data T1 circuit.[31]

Broadband

[edit]

The term broadband gained widespread adoption in the late 90s to describe internet access technology exceeding the 56 kilobit/s maximum of dialup. There are many broadband technologies, such as various DSL (Digital Subscriber Line) technologies and cable broadband.

DSL technologies such as ADSL, HDSL and VDSL use telephone lines (wires that were installed by a telephone company and originally intended for use by a telephone subscriber) but do not utilize most of the rest of the telephone system. Their signals are not sent through ordinary phone exchanges, but are instead received by special equipment (a DSLAM) at the telephone company central office.

Because the signal does not pass through the telephone exchange, no "dialing" is required, and the bandwidth constraints of an ordinary voice call are not imposed. This allows much higher frequencies, and therefore much faster speeds. ADSL in particular is designed to permit voice calls and data usage over the same line simultaneously.

Similarly, cable modems use infrastructure originally intended to carry television signals, and like DSL, typically permit receiving television signals at the same time as broadband internet service.

Other broadband modems include satellite modems and power line modems.

Terminology

[edit]Different terms are used for broadband modems, because they are frequently contain more than just a modulation/demodulation component.

Because high speed connections are frequently used by multiple computers at once, many broadband modems do not have direct (e.g. USB) PC connections, but connect over a network such as Ethernet or Wi-Fi. Early broadband modems offered Ethernet handoff allowing the use of one or more public IP addresses, but no other services such as NAT and DHCP that would allow multiple computers to share one connection. This led to many consumers purchasing separate "broadband routers," placed between the modem and their network, to perform these functions.

Eventually, ISPs began providing residential gateways which combined the modem and broadband router into a single package that provided routing, NAT, security features, and even Wi-Fi access in addition to modem functionality, so that subscribers could connect their entire household without purchasing any extra equipment. Even later, these devices were extended to provide "triple play" features such as telephony and television service. Nonetheless, these devices are still often referred to simply as "modems" by service providers and manufacturers.

Consequently the terms "modem," "router" and "gateway" are now used interchangeably in casual speech, but in a technical context "modem" may carry a specific connotation of basic functionality with no routing or other features, while the other terms describe a device with features such as NAT.

Broadband modems may also handle authentication such as PPPoE. While it is often possible to authenticate a broadband connection from a users PC, as was the case with dial-up internet service, moving this task to the broadband modem allows it to establish and maintain the connection itself, which makes sharing access between PCs easier since each one does not have to authenticate separately. Broadband modems typically remain authenticated to the ISP as long as they are powered on.

Radio

[edit]

Any communication technology sending digital data wirelessly involves a modem. This includes direct broadcast satellite, WiFi, WiMax, mobile phones, GPS, Bluetooth and NFC.

Modern telecommunications and data networks also make extensive use of radio modems where long distance data links are required. Such systems are an important part of the PSTN, and are also in common use for high-speed computer network links to outlying areas where fiber optic is not economical.

Wireless modems come in a variety of types, bandwidths, and speeds. Wireless modems are often referred to as transparent or smart. They transmit information that is modulated onto a carrier frequency to allow many wireless communication links to work simultaneously on different frequencies.[relevant?]

Transparent modems operate in a manner similar to their phone line modem cousins. Typically, they were half duplex, meaning that they could not send and receive data at the same time. Typically, transparent modems are polled in a round robin manner to collect small amounts of data from scattered locations that do not have easy access to wired infrastructure. Transparent modems are most commonly used by utility companies for data collection.

Smart modems come with media access controllers inside, which prevents random data from colliding and resends data that is not correctly received. Smart modems typically require more bandwidth than transparent modems, and typically achieve higher data rates. The IEEE 802.11 standard defines a short range modulation scheme that is used on a large scale throughout the world.

Mobile broadband

[edit]

Modems which use a mobile telephone system (GPRS, UMTS, HSPA, EVDO, WiMax, etc.), are known as mobile broadband modems (sometimes also called wireless modems). Wireless modems can be embedded inside a laptop, mobile phone or other device, or be connected externally. External wireless modems include connect cards, USB modems, and cellular routers.

Most GSM wireless modems come with an integrated SIM cardholder (i.e. Huawei E220, Sierra 881.) Some models are also provided with a microSD memory slot and/or jack for additional external antenna, (Huawei E1762, Sierra Compass 885.)[32][33]

The CDMA (EVDO) versions do not typically use R-UIM cards, but use Electronic Serial Number (ESN) instead.

Until the end of April 2011, worldwide shipments of USB modems surpassed embedded 3G and 4G modules by 3:1 because USB modems can be easily discarded. Embedded modems may overtake separate modems as tablet sales grow and the incremental cost of the modems shrinks, so by 2016, the ratio may change to 1:1.[34]

Like mobile phones, mobile broadband modems can be SIM locked to a particular network provider. Unlocking a modem is achieved the same way as unlocking a phone, by using an 'unlock code'.[citation needed]

Optical modem

[edit]

A modem that connects to a fiber optic network is known as an optical network terminal (ONT) or optical network unit (ONU). These are commonly used in fiber to the home installations, installed inside or outside a house to convert the optical medium to a copper Ethernet interface, after which a router or gateway is often installed to perform authentication, routing, NAT, and other typical consumer internet functions, in addition to "triple play" features such as telephony and television service.

Fiber optic systems can use quadrature amplitude modulation to maximize throughput. 16QAM uses a 16-point constellation to send four bits per symbol, with speeds on the order of 200 or 400 gigabits per second.[35][36] 64QAM uses a 64-point constellation to send six bits per symbol, with speeds up to 65 terabits per second. Although this technology has been announced, it may not yet be commonly used.[37][38][39]

Home networking

[edit]Although the name modem is seldom used, some high-speed home networking applications do use modems, such as powerline ethernet. The G.hn standard for instance, developed by ITU-T, provides a high-speed (up to 1 Gbit/s) local area network using existing home wiring (power lines, phone lines and coaxial cables). G.hn devices use orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM) to modulate a digital signal for transmission over the wire.

As described above, technologies like Wi-Fi and Bluetooth also use modems to communicate over radio at short distances.

"Null Modem"

[edit]

The phrase "null modem" was common parlance in the heydey of RS-232 communication between computers, but as the name suggests, it in fact describes the absence of a modem.

A null modem cable is a specially wired cable connected between the serial ports of two personal computers, with the transmit and receive lines reversed. The name referred to the use of this type of cable to connect two computers for applications where a modem would typically be used, and the same software used with modems (such as Procomm or Minicom) could be used with this type of connection.

A null modem adapter is a small device with plugs on both end which is placed on the end of a normal "straight-through" serial cable to convert it into a null-modem cable.

Short-haul modem

[edit]A "short haul modem" is a device that bridges the gap between leased-line and dial-up modems. Like a leased-line modem, they transmit over "bare" lines with no power or telco switching equipment, but are not intended for the same distances that leased lines can achieve. Ranges up to several miles are possible, but significantly, short-haul modems can be used for medium distances, greater than the maximum length of a basic serial cable but still relatively short, such as within a single building or campus. This allows a serial connection to be extended for perhaps only several hundred to several thousand feet, a case where obtaining an entire telephone or leased line would be overkill.

While some short-haul modems do in fact use modulation, low-end devices (for reasons of cost or power consumption) are simple "line drivers" that increase the level of the digital signal but do not modulate it. These are not technically modems, but the same terminology is used for them.[40]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ inventors, Mary Bellis Mary Bellis wrote on the topics of; Years, Inventions for 18; Producer, Was a Film; director. "Where Did the Modem Come From?". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "National Security Agency Central Security Service > About Us > Cryptologic Heritage > Historical Figures and Publications > Publications > WWII > Sigsaly - The Start of the Digital Revolution". www.nsa.gov. Retrieved 2020-08-13.

- ^ Manjoo, Farhad (2009-02-24). "The unrecognizable Internet of 1996". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- ^ Brenner, Joanna. "3% of Americans use dial-up at home". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Modem entry". Archived from the original on 2014-07-11.

- ^ Internet, Tamsin Oxford 2009-12-26T11:00:00 359Z. "Getting connected: a history of modems". TechRadar. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Mark Anderson. "David Forney: The Man Who Launched a Million Modems". 2016.

- ^ IEEE History Center. "Gottfried Ungerboeck Oral History". Archived from the original on June 25, 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ^ Ungerboeck, Gottfried (1982). "Channel coding with multilevel/phase signals". IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. IT-28: 55–67.

- ^ "Modem compression: V.44 against V.42bis". Pricenfees.com. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ^ "Re: Modems FAQ". Archived from the original on January 4, 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-18. - Wolfgang Henke.

- ^ Held, Gilbert (2000). Understanding Data Communications: From Fundamentals to Networking Third Edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. pp. 68–69.

- ^ "x2 White Paper". web.archive.org. 1997-06-07. Retrieved 2020-06-29.

- ^ Ross, John A. (John Allan), 1955- (2001). Telecommunication technologies : voice, data & fiber-optic applications. Indianapolis, Ind.: Prompt. p. 185. ISBN 0-7906-1225-9. OCLC 45745196. Archived from the original on 2019-10-19.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Greenstein, Shane; Stango, Victor (2006). Standards and Public Policy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–132. ISBN 978-1-139-46075-0. Archived from the original on 2017-03-24.

- ^ "Agreement reached on 56K Modem standard". International Telecommunication Union. 9 February 1998. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ^ "V.92: Enhancements to Recommendation V.90". www.itu.int. Retrieved 2020-06-29.

- ^ "V.92 - News & Updates". November and October 2000 updates. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ a b "The History of the Modem". Techopedia.com. Retrieved 2020-08-13.

- ^ "The Modem | Invention & Technology Magazine". www.inventionandtech.com. Retrieved 2020-08-13.

- ^ "USRobotics 56K Modem Education: What are the different types of modems?". support.usr.com. Retrieved 2020-08-11.

- ^ tsbmail (2011-04-15). "Data communication over the telephone network". Itu.int. Archived from the original on 2014-01-27. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "29.2 Historical Modem Protocols". tldp.org. Archived from the original on 2014-01-02. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ^ "concordia.ca — Data Communication and Computer Networks" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-07. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ^ "Group 3 Facsimile Communication". garretwilson.com. 2013-09-20. Archived from the original on 2014-02-03. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ^ "upatras.gr - Implementation of a V.34 modem on a Digital Signal Processor" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-03-06. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ^ Jones, Les. "Bonding: 112K, 168K, and beyond". 56K.COM. Archived from the original on 1997-12-10.

- ^ "Software Publishing Association Unveils New Data". Read.Me. Computer Gaming World. May 1994. p. 12. Archived from the original on 2014-07-03.

- ^ Suzanne Choney. "AOL still has 3.5 million dial-up subscribers - Technology on NBCNews.com". Archived from the original on 2013-01-01. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ^ ID, FCC. "E110 56K DATA / FAX VOICE SPEAKPHONE EXTERNAL MODEM User Manual PTT Turbocomm Tech ". FCC ID. Retrieved 2020-08-13.

- ^ "MODEMS lease line modem". www.data-connect.com. Retrieved 2020-08-11.

- ^ "HUAWEI E1762,HSPA/UMTS 900/2100 Support 2Mbps (5.76Mbps ready) HSUPA and 7.2Mbps HSDPA services". 3gmodem.com.hk. Archived from the original on 2013-05-10. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ "Sierra Wireless Compass 885 HSUPA 3G modem". The Register. Archived from the original on 2013-01-04. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ^ Lawson, Stephen (May 2, 2011). "Laptop Users Still Prefer USB Modems". PCWorld. IDG Consumer & SMB. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ^ Michael Kassner (February 10, 2015). "Researchers double throughput of long-distance fiber optics". TechRepublic. Archived from the original on November 9, 2016.

- ^ Bengt-Erik Olsson; Anders Djupsjöbacka; Jonas Mårtensson; Arne Alping (6 Dec 2011). "112 Gbit/s RF-assisted dual carrier DP-16-QAM transmitter using optical phase modulator" (PDF). Optics Express. 19 (26). Optical Society of America: B784-9. Bibcode:2011OExpr..19B.784O. doi:10.1364/oe.19.00b784. PMID 22274103.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Stephen Hardy (March 17, 2016). "ClariPhy targets 400G with new 16-nm DSP silicon". LIGHTWAVE. Archived from the original on November 9, 2016.

- ^ "ClariPhy Shatters Fiber and System Capacity Barriers with Industry's First 16nm Coherent Optical Networking Platform". optics.org. 17 Mar 2016.

- ^ "Nokia Bell Labs achieve 65 Terabit-per-second transmission record for transoceanic cable systems". Noika. 12 October 2016. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ "Modem". www.trine2.net.au. Retrieved 2020-08-13.

External links

[edit]- Hayes-compatible Modems and AT Commands from the Serial Data Communications Programming Wikibook

- International Telecommunications Union ITU: Data communication over the telephone network

- "Columbia University - Protocols Explained". Archived from the original on June 19, 2006. Retrieved August 12, 2007. – no longer available, archived version

- Basic handshakes & modulations – V.22, V.22bis, V.32 and V.34 handshakes

- Getting connected: a history of modems – techradar

- Data/FAX Modem Transmission Modulation Systems – baud rates and modulation schemes

Category:Computer-related introductions in 1958 Category:American inventions Category:Bulletin board systems Category:Logical link control Category:Physical layer protocols