User:Gdytor/sandbox

Religious Fertility Effect

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Sociology |

|---|

|

Religiosity and fertility are two sociological factors which can be seen to have influence over each other with fertility rates, fertility decisions and other reproductive behaviours and attitudes differing amongst people of various religious and non-religious groups.

Whilst the “Religious Fertility Effect” is not explicitly defined verbatim as a scientific or sociological concept, the relationship between the two factors has been researched and reported on heavily. Generally, a higher importance of religion in one’s life, or religiosity, has been reflected with greater intended fertility. [1]

There are a number of factors that can be seen to cause this, such as the relationship and dynamic between partners in religious households, [2] specific religious teachings and guidelines promoting fertility [3] and varying attitudes towards the use of contraception and practice of abortion.

Religiosity and Fertility

[edit]

Studies from the 1950s and 1960s reported higher fertility in Catholics compared to other religious and non-religious groups in Western countries [4]. The prohibition of contraception by the Church was the main contributor to this. However, by the 1970s these differences amongst religious groups had, for the most part, disappeared [5] [6], whilst the gap between the religious and non-religious remained [7].

Another study from 1996 found that when individuals marry within their religious groups, fertility rates and family size is found to be larger. This was concluded to be a result of the bargaining effect and marital stability effect, where partners are likely to have matching preferences regarding fertility decisions and are less likely to separate (especially in the context of religious households). [2]

Further studies in Western countries from the late 2000s report clear differences in fertility rates by religious intensity. This intensity was determined by church attendance rates as well as self-reported religiosity.[8] [9]

In comparison to other religious groups in Europe, Muslim families have more children, but a convergence over time is evident, reflecting the impact of social and cultural factors over religious ones.[10] [11].This trend was also observed in Muslim majority countries by Abbasi-Shavazi and Jones (2005)[12] and Abbasi-Shavazi and Torabi (2012)[13] who also argue that this could be explained, for the most part, by socio-economic and cultural factors.

Fertility trends globally have historically shown lower rates of fertility a characteristic of more developed countries, whilst higher rates of fertility are common amongst less developed and developing countries. [14] However, this has found to not always the case, especially where religious intensity is prevalent. For example, in Israel, a society that exhibits higher levels of development and affluence than many in Europe and East Asia, continues to show high fertility and intentions, with the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) averaging 3.0 since the 1980s [15]. In addition to pro-natalist policies, religious diversity and intensity has sustained these rates with groups such as ‘ultra-religious’ Jews, maintaining traditional values in tandem with very high fertility.[16][17]

Contraception

[edit]

The Catholic Church opposed artificial birth control as early as can historically trace. Most Protestant groups on the other hand have come to accept birth control on the basis of “Biblically allowable freedom of conscience” [18]. However, other groups believe birth control to promote promiscuous behaviour outside of marriage. [19]

The Qur'an does not discuss the morality of contraception, however, it does encourage procreation. [3] The Coitus interruptus method of birth control, was practised during the time of Muhammad and he never explicitly opposed it. [3][20] On the basis of this, Modern day scholars permit other forms of contraception, as long as both parties consent, it does not cause permanent sterility and does not cause harm to the body. [3]

In Hinduism, texts such as The Mahabharata state that the termination of an embryo is sinful. [21] However, other texts such as The Dharma explains it violates the Ahimsa (non-violent rule of conduct) when conceiving more than can be supported. [22] This is particularly evident in India, where a large and dense population, has resulted in much of the discussion of contraception focusing on overpopulation personal and religious morals and ethics.[23]

Jewish views on contraception depend on the branch followed, i.e. Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform. Orthodox Jews only consider acceptable under specific circumstances, such as if the couple already has two children. Conservative Judaism encourages traditional views and morals regarding contraception, however, is willing to make exceptions on the grounds of fitting into the practices of modern Western society. Reform Judaism permits individual followers exercise their own judgement on if and how they use birth control.[24]

Attitudes towards contraception in Buddhism are founded on the idea that killing is wrong. It is commonly viewed that methods that prevent conception are permissible whilst methods that stop the development of a fertilised egg is not.[25]

Abortion

[edit]

There is no explicit prohibition of abortion in the "Old" or "New Testament" in the Christian Bible.[26]

Other than indirect abortion,[27] deliberate abortion is viewed as immoral and strongly opposed by the Catholic,[28] Eastern Orthodox [29], Oriental Orthodox and most evangelical Protestant churches. Whilst other mainline Protestant groups are more accepting of the practice. [30]

Whilst there are differing opinions, the general consensus regarding the termination of a pregnancy in Islam is before 120 days – the point after which the foetus is believed to become a living a soul according.[31]

Abortion is not explicitly mentioned in the sacred Islam text, the Qur’an, however, intentional murder is condemned. In all schools of Islamic thought, it is permissible in order to save a mother’s life.[32]

Abortion is strongly opposed in the classical texts of Hinduism. Additionally, scholars and women's rights advocates have given support to banning sex-selective abortions, due to the prevalence of abortion in Hindu culture particularly in India where the cultural preference for sons overrules the religious ban on abortion. However, cases where the life of the mother is at risk or life-threatening developmental anomaly occur in the foetus it is supported.[33]

In Judaism, the Talmud, Responsa and rabbinic literature are referred to when dealing with the issue of abortion.

Orthodox Jews only permit abortion where the life or health of the mother is at risk.[34] Whilst other denominations support the right for safe and accessible abortions.[31]

No official view in regard to abortion exists in Buddhism, this is further complicated by the belief that there is no single starting point in a life.[35] [36] Additionally, the Dalai Lama has commented on the issue as “negative” but should be considered on a case by case situation under certain circumstances. [37]

Current Rates

[edit]

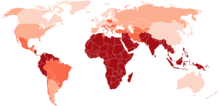

Christianity: Globally for the 2010 to 2015 period, the Christian community has a Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 2.7 children per woman. This is higher than that of the world’s overall population which currently sits at 2.5 children per woman and the replacement level, the rate necessary for maintaining a stable population, of 2.1 children per woman.[38]

Islam: Muslims have a TFR of 3.1 children per woman which is also higher than that of the world’s overall population for the 2010 to 2015 period (2.5). This is the main driver underpinning the projected growth of the Muslim population around the world, where the TFR for Muslims exceeds the replacement level in all regions. This reflects the expected growth in the Muslim population in both absolute and relative terms.[39]

Unaffiliated: Compared to that of the world population, the religiously unaffiliated have lower rates of fertility, currently with a TFR of 1.7 children per woman.[40]

Hinduism: Over the 2010 to 2015 period, Hindus globally have had a TFR of 2.4 children per woman. This is comparable to the global TFR of 2.5 and exceeds the replacement level of 2.1.[41]

Buddhism: The Buddhist population have a TFR of 1.6 children per woman, this is lower than both the world average and the replacement level of 2.5 and 2.1 respectively. By not being greater than or equal to the replacement level, means the Buddhist population will be unable to maintain their current population size, all else remaining equal.[42]

Judaism: Jews have had a TFR of 2.3 children per woman for the 2010 to 2015 period, below the global TFR but above the replacement level. A geographical breakdown reveals the TFR of the Jewish population is much higher in the Middle East and North Africa at 2.8 children per woman, compared to 2.0 in North American and 1.8 in Europe.[43]

Outlook/Projections

[edit]

In some contexts, the religious based differences in fertility have a crucial impact on a populations’ future religious composition.[44] [45][46] With the behaviours and attitudes of religious groups in regard to fertility decisions, for example the use contraception and abortion, the decline of religion should result in a negative effect on fertility, but with secular countries such as Sweden and France displaying higher fertility rates and countries like China, Brazil and Iran joining the growing list of low fertility countries; [14] the link may be more complex, especially when attempting to forecast future rates of fertility against religiosity amongst religious and non-religious groups and countries.

Christianity: Globally, it is expected that the Christian population will growth to 2.9 billion in 2050 from 2.2 billion (2010), the annual growth rate is predicted to remain in line with the falling growth rate of the world’s population (1.1% 2015 to 0.4% in 2050). Whilst the percentage of Christians in the global population is projected to remain at the 31% it is currently; the distribution of the population is set to change. For the period 2010 to 2050, the sub-Saharan Africa Christian population is expected to growth from 24% to 38%, whilst the portion in Europe will fall from 26% to 16%. [38] Christians in Europe are projected to fall from three-quarters of the population to under two-thirds. This decline will also be seen in North America (78% in 2010 to 66% in 2050 of the US population). Conversely, sub-Saharan Africa’s Christian population is expected to double, from 517 million to 1.1 billion over the same period. [47]

Islam: The Muslim population globally is projected to increase rapidly, growing to 2.8 billion in 2050 from 1.6 billion (2010) at a growth rate twice that of the global population. As a result, percentage of Muslims in the global population will increase from 23% to 30% in this same time period.[39] Due largely to high fertility, the sub-Saharan Africa and Middle East-North Africa regions are projected to drive increases in the global Muslim and Christian populations. Interestingly, in developed regions such as Europe and North America, which overall have slow population growth and fertility rates, are still expected to have increases in their Muslim populations (2.1% in North American and in Europe it will double to 10% by 2050).[47]

Unaffiliated: The religiously unaffiliated population is projected to grow slightly from 1.1 billion in 2010 to 1.2 billion in 2040. However, over this period the global population is expected to grow at a more rapid rate, thus reducing the percentage globally. This is due to the older population and lower fertility rate of the unaffiliated globally compared to religious groups.[40] The unaffiliated in all regions of the world are expected to grow in percentage terms, except for in the Asia-Pacific where declining population growth as whole is expected to case a decline in the religiously unaffiliated as they currently make up over 75% of the population. [47]

Hinduism: The Hindu population is expected to rise slightly from 1 billion (2010) to 1.4 billion (2050). This is projected to be at the same growth rate of the world’s population (a slowing rate from around 1.1% to 0.4%, 2010 to 2050), thus maintaining the same share of the global population at 15%.[41] Hindus, who are highly concentrated in India, are projected to grow at the global rate due to India’s high fertility and young population, this is expected to feed into growth in developed nations such as in Europe through immigration. The number of Hindus in Europe is expected to roughly double, from 1.4 million to nearly 2.7 million as a result.[47]

Buddhism: Unlike the other religious groups, the global Buddhist population is expected to grow for the 2010 to 2030 period (488 million to 511 million), and then decline from there on after to about 486 million in 2050. Their share of the global population is expected to fall from 7% to 5% as a result.[42]

Judaism: The global Jewish population, currently at 14 million, is projected to increase to about 16 million by 2050, maintaining the 0.2% share of the global population it currently holds.[43]

It is important to note that whilst the populations of religious groups are increasing as detailed by a Pew Research Report, the rate at which they are growing is projected to fall across the board.

Developing nation’s populations on a whole are growing, as a result, religious groups within these nations are growing and are projected to continue doing so.[47] Comparatively, whilst an overwhelming majority of developed nations are experiencing very low fertility rates or even declining population numbers, Islam is an outlier in that it is expected to continue growing in all countries, regardless if they are experiencing a growing or falling population.[47]

Sources

[edit]- ^ Hayford, S. R., & Morgan, S. P. (2008). Religiosity and Fertility in the United States: The Role of Fertility Intentions. Social forces; a scientific medium of social study and interpretation, 86(3), 1163–1188. doi:10.1353/sof.0.0000 Retrieved 30 April 2019

- ^ a b Lehrer, E. (2009). Religion, economics, and demography: the effects of religion on education, work, and the family. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781135990664. Retrieved 11 May 2019

- ^ a b c d Yusuf, J. B. (2014). Contraception and Sexual and Reproductive Awareness Among Ghanaian Muslim Youth: Issues, Challenges, and Prospects for Positive Development. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014541771 Retrieved 21 May 2019

- ^ Jones, G.W. and Nortman, D. 1968 ‘Roman Catholic Fertility and Family Planning: A Comparative Review of the Research Literature’. Studies in Family Planning, 1: 1–27. Retrieved 10 May 2019

- ^ Derosas, R. and van Poppel, F.W.A. 2006 Religion and the Decline of Fertility in the Western World. Springer: Dordrecht. Retrieved 12 May 2019

- ^ Westoff, C.F. and Jones, E.F. 1979 ‘The End of “Catholic” Fertility’. Demography, 16: 209–17. Retrieved 12 May 2019

- ^ Philipov, D. and Berghammer, C. 2007 ‘Religion and Fertility Ideals, Intentions and Behaviour: A Comparative Study of European Countries’. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 5: 271–305. Retrieved 12 May 2019

- ^ Philipov, D. and Berghammer, C. 2007 ‘Religion and Fertility Ideals, Intentions and Behaviour: A Comparative Study of European Countries’. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 5: 271–305. Retrieved 10 May 2019

- ^ Zhang, L. 2008 ‘Religious Affiliation, Religiosity and Male and Female Fertility’. Demographic Research, 18: 233–62. Retrieved 3 April 2019

- ^ Pew Research Center 2011 The Future of the Global Muslim Population. Projections for 2010–2030. Pew Research Center: Washington, DC Retrieved 20 May 2019

- ^ Westoff, C.F. and Frejka, T. 2007 ‘Religiousness and Fertility among European Muslims’. Population and Development Review, 33: 785–809. Retrieved 20 May 2019

- ^ Abbasi-Shavazi, M.J. and Jones, G.W. 2005 ‘Socio-economic and Demographic Setting of Muslim Populations’. In: Jones, G.W. and Karim, M.S. (eds) Islam, the State and Population, pp. 9–39. Hurst and Co.: London. Retrieved 20 May 2019

- ^ Abbasi-Shavazi, M.J. and Torabi, F. 2012 ‘Women’s Education and Fertility in Islamic Countries’. In: Population Dynamics in Muslim Countries, pp. 43–62. Springer: Dordrecht Retrieved 20 May 2019

- ^ a b Lutz, W., Butz, W., & KC, S. (2014). World population and human capital in the twenty-first century ed. by Wolfgang Lutz, William P. Butz and Samir KC (pp. 40-145). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 3 April 2019

- ^ CBS 2011 Statistical Abstract of Israel 2011. Chapter 3: Vital Statistics (No. 62). The Central Bureau of Statistics: Jerusalem. Retrieved 20 May 2019

- ^ Bystrov, E. 2012 ‘The Second Demographic Transition in Israel: One for All?’ Demographic Research, 27: 261–98 Retrieved 21 May 2019

- ^ DellaPergola, S. 2007 ‘Actual, Intended, and Appropriate Family Size in Israel: Trends, Attitudes and Policy Implications: A Preliminary Report’. Avraham Harman Institute of Contemporary Jewry: Jerusalem. Retrieved 18 May 2019

- ^ Campbell, Flann (Nov 1960). "Birth Control and the Christian Churches". Population Studies. Population Investigation Committee. 14 (2): 131–147. doi:10.2307/2172010. JSTOR 2172010. Retrieved 22 May 2019

- ^ Citizen Link (2005). "Abstinence Policy"the original. Retrieved 2019-5-23

- ^ Contraception: Permissible?. (2010). Living Shari`Ah. Retrieved from https://archive.islamonline.net/?p=1000 Retrieved 21 May 2019

- ^ Mahabharata (p. Section LXXXIII). Retrieved 21 May 2019

- ^ Stacey, D. (2019). What Are Religious Views on Birth Control?. Retrieved from https://www.verywellhealth.com/what-are-religious-views-on-birth-control-906618 Retrieved 21 May 2019

- ^ BBC - Religions - Hinduism: Contraception. (2009). BBC- Religion and Ethics. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/hinduism/hinduethics/contraception.shtml Retrieved 21 May 2019

- ^ BBC - Religions - Judaism: Contraception. (2009). BBC- Religion and Ethics. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism/jewishethics/contraception.shtml Retrieved 18 May 2019

- ^ BBC - Religions - Buddhism: Contraception. (2009). BBC- Religion and Ethics. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/buddhism/buddhistethics/contraception.shtml Retrieved 19 May 2019

- ^ Luker, K. (1985). Abortion and the Politics of Motherhood (pp. 184-185). Los Angeles: University of California Press. Retrieved 19 May 2019

- ^ Kaczor, C. (2015). The ethics of abortion : women's rights, human life, and the question of justice (2nd ed., p. 187). New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. Retrieved 19 May 2019

- ^ Pius XII (1951). Allocution to Large Families.. Vatican: Pius XII Retrieved 19 May 2019

- ^ "The Orthodox Perspective on Abortion at the occasion of the National Sanctity of Human Life Day 2009". Retrieved 2019-5-20

- ^ The Office of the General Assembly Presbyterian Church (U.S.A. (1992). Special Committee on Problem Pregnancies and Abortion. Louisville: Office of the General Assembly Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). Retrieved from https://www.pcusa.org/site_media/media/uploads/oga/pdf/problem-pregnancies.pdf Retrieved 19 May 2019

- ^ a b Pew Forum. (2013). Religious Groups’ Official Positions on Abortion. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewforum.org/2013/01/16/religious-groups-official-positions-on-abortion/ Retrieved 19 May 2019

- ^ BBC - Religions - Islam: Abortion. (2008). BBC – Religion and Ethics. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/islamethics/abortion_1.shtml Retrieved 19 May 2019

- ^ BBC - Religions - Hinduism: Abortion. (2006). BBC – Religion and Ethics. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/hinduism/hinduethics/abortion_1.shtml Retrieved 19 May 2019

- ^ Bank, R. (2002). The everything Judaism book (p. 186). Avon, Mass.: Adams Media. Retrieved 19 May 2019

- ^ BBC - Religions - Buddhism: Abortion. (2009). BBC- Religion and Ethics. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/buddhism/buddhistethics/abortion.shtml Retrieved 18 May 2019

- ^ Keown, D. (2009). Buddhism and Abortion. Retrieved from https://www.patheos.com/resources/additional-resources/2009/08/buddhism-and-abortion Retrieved 16 May 2019

- ^ Dreifus, C. (1993). The New York Times. The Dalai Lama. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/1993/11/28/magazine/the-dalai-lama.html Retrieved 20 May 2019

- ^ a b Pew Research Center. (2015). The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050 (pp. 59-65). Pew Research Center.

- ^ a b Pew Research Center. (2015). The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050 (pp. 70-76). Pew Research Center.

- ^ a b Pew Research Center. (2015). The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050 (pp. 81-87). Pew Research Center.

- ^ a b Pew Research Center. (2015). The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050 (pp. 92-98). Pew Research Center.

- ^ a b Pew Research Center. (2015). The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050 (pp. 102-108). Pew Research Center.

- ^ a b Pew Research Center. (2015). The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050 (pp. 133-139). Pew Research Center.

- ^ Hout, M., Greeley, A. and Wilde, M.J. 2001 ‘The Demographic Imperative in Religious Change in the United States’. American Journal of Sociology, 107: 468– 500 Retrieved 13 May 2019

- ^ Kaufmann, E. 2010 Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth? Demography and Politics in the Twenty-First Century. Profile Books: London. Retrieved 13 May 2019

- ^ Skirbekk, V., Kaufmann, E. and Goujon, A. 2010 ‘Secularism, Fundamentalism, or Catholicism? The Religious Composition of the United States to 2043’. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 49: 293–310. Retrieved 20 May 2019

- ^ a b c d e f Pew Research Center. (2015). The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050 (pp. 15-17). Pew Research Center.

Category:Religion Category:Religion and science Category:Fertility Category:Religious behaviour and experience