User:Garfun/sandbox

Just playing with editing here... this is a subject I know something about.

Interferometric synthetic aperture radar, commonly abbreviated InSAR or IfSAR, is a geodetic remote sensing technique that can be used to measure displacements and/or topography of the Earth's surface. The technique uses radar images acquired by sensors on satellites or aeroplanes, giving the technique global coverage, and allowing the study of areas that would otherwise be inaccessible. Applications include mapping the deformation of the Earth due to geological phenomena such as earthquakes, landslides, glaciers or movements of magma in volcanoes, engineering applications such as monitoring stability of land or buildings, and the generation of digital elevation models.[1] [2] [3]

Technique

[edit]Synthetic aperture radar

[edit]

Synthetic aperture radar (SAR) is a form of radar in which sophisticated processing of radar data is used to produce a very narrow effective beam. It can only be used by moving instruments over relatively immobile targets. It is a form of active remote sensing - the antenna transmits radiation which is then reflected back from the target, as opposed to passive sensing where the reflections detected come from ambient illumination. The image acquisition is therefore independent of the natural illumination and images can be taken at night. Radar uses electromagnetic radiation with microwave frequencies; the atmospheric absorption at typical radar wavelengths is very low, meaning observations are not prevented by cloud cover.

Phase

[edit]

Most SAR applications make use of the amplitude of the return signal, and ignore the phase data. However interferometry uses the phase of the reflected radiation. Since the outgoing wave is produced by the satellite, the phase is known, and can be compared to the phase of the return signal. The phase of the return wave depends on the distance to the ground, since the path length to the ground and back will consist of a number of whole wavelengths plus some fraction of a wavelength. This is observable as a phase difference or phase shift in the returning wave. The total distance to the satellite (i.e. the number of whole wavelengths) is not known, but the extra fraction of a wavelength can be measured extremely accurately.

In practice, the phase is also affected by several other factors, which together make the raw phase return in any one SAR image essentially arbitrary, with no correlation from pixel to pixel. To get any useful information from the phase, some of these effects must be isolated and removed. Interferometry uses two images of the same area taken from the same position (or for topographic applications slightly different positions) and finds the difference in phase between them, producing an image known as an interferogram. This is measured in radians of phase difference and, due to the cyclic nature of phase, is recorded as repeating fringes which each represent a full 2π cycle.

Factors affecting phase

[edit]The most important factor affecting the phase is the interaction with the ground surface. The phase of the wave may change on reflection, depending on the properties of the material. The reflected signal back from any one pixel is the summed contribution to the phase from many smaller 'targets' in that ground area, each with different dielectric properties and distances from the satellite, meaning the returned signal is arbitrary and completely uncorrelated with that from adjacent pixels. Importantly though, it is consistent - provided nothing on the ground changes the contributions from each target should sum identically each time, and hence be removed from the interferogram.

Once the ground effects have been removed, the major signal present in the interferogram is a contribution from orbital effects. For interferometry to work, the satellites must be as close as possible to the same spatial position when the images are acquired. This means that images from two different satellite platforms with different orbits cannot be compared, and for a given satellite data from the same orbital track must be used. In practice the perpendicular distance between them, known as the baseline, is often known to within a few centimetres but can only be controlled on a scale of tens to hundreds of metres. This slight difference causes a regular difference in phase that changes smoothly across the interferogram and can be modelled and removed.

The slight difference in satellite position also alters the distortion caused by topography, meaning an extra phase difference is introduced by a stereoscopic effect. The longer the baseline, the smaller the topographic height needed to produce a fringe of phase change - known as the altitude of ambiguity. This effect can be exploited to calculate the topographic height, and used to produce a digital elevation model (DEM).

If the height of the topography is already known, the topographic phase contribution can be calculated and removed. This has traditionally been done in two ways. In the two-pass method, elevation data from an externally-derived DEM is used in conjunction with the orbital information to calculate the phase contribution. In the three-pass method two images acquired a short time apart are used to create an interferogram, which is assumed to have no deformation signal and therefore represent the topographic contribution. This interferogram is then subtracted from a third image with a longer time separation to give the residual phase due to deformation.

Once the ground, orbital and topographic contributions have been removed the interferogram contains the deformation signal, along with any remaining noise (see Difficulties with InSAR). The signal measured in the interferogram represents the change in phase caused by an increase or decrease in distance from the ground pixel to the satellite, therefore only the component of the ground motion parallel to the satellite line of sight vector will cause a phase difference to be observed. For sensors like ERS with a small incidence angle this measures vertical motion well, but is insensitive to horizontal motion perpendicular to the line of sight. It also means that vertical motion and components of horizontal motion parallel to the plane of the line of sight cannot be separately resolved.

One fringe of phase difference is generated by a ground motion of half the wavelength, since this corresponds to a whole wavelength increase in the two-way travel distance. Phase shifts are only resolvable relative to other points in the interferogram. Absolute deformation can be inferred by assuming one area in the interferogram (for example a point away from expected deformation sources) experienced no deformation, or by using a ground control (GPS or similar) to establish the absolute movement of a point.

Difficulties with InSAR

[edit]A variety of factors govern the choice of images which can be used for interferometry. The simplest is data availability - radar instruments used for interferometry commonly don't operate continuously, acquiring data only when programmed to do so. For future requirements it may be possible to request acquisition of data, but for many areas of the world archived data may be sparse. Data availability is further constrained by baseline criteria. Availability of a suitable DEM may also be a factor for two-pass InSAR; commonly 90m SRTM data may be available for many areas, but at high latitudes or in areas of poor coverage alternative datasets must be found.

A fundamental requirement of the removal of the ground signal is that the sum of phase contributions from the individual targets within the pixel remains constant between the two images and is completely removed. However, there are several factors that can cause this criterion to fail. Firstly the two images must be accurately co-registered to a sub-pixel level to ensure that the same ground targets are contributing to that pixel. There is also a geometric constraint on the maximum length of the baseline - the difference in viewing angles must not cause phase to change over the width of one pixel by more than a wavelength. The effects of topography also influence the condition, and baselines need to be shorter if terrain gradients are high. Where co-registration is poor or the maximum baseline is exceeded the pixel phase will become incoherent - the phase becomes essentially random from pixel to pixel rather than varying smoothly, and the area appears noisy. This is also true for anything else that changes the contributions to the phase within each pixel, for example changes to the ground targets in each pixel caused by vegetation growth, landslides, agriculture or snow cover.

Another source of error present in most interferograms is caused by the propagation of the waves through the atmosphere. If the wave travelled through a vacuum it should theoretically be possible (subject to sufficient accuracy of timing) to use the two-way travel-time of the wave in combination with the phase to calculate the exact distance to the ground. However the velocity of the wave through the atmosphere is lower than the speed of light in a vacuum, and depends on air temperature, pressure and the partial pressure of water vapour.[4] It is this unknown phase delay that prevents the integer number of wavelengths being calculated. If the atmosphere was horizontally homogeneous over the length scale of an interferogram and vertically over that of the topography then the effect would simply be a constant phase difference between the two images which, since phase difference is measured relative to other points in the interferogram, would not contribute to the signal. However the atmosphere is laterally heterogeneous on length scales both larger and smaller than typical deformation signals. This spurious signal can appear completely unrelated to the surface features of the image, however in other cases the atmospheric phase delay is caused by vertical inhomogeneity at low altitudes and this may result in fringes appearing to correspond with the topography.

Producing interferograms

[edit]The processing chain used to produce interferograms varies according to the software used and the precise application, but will usually include some combination of the following steps.

Two SAR images are required to produce an interferogram; these may be obtained pre-processed, or produced from raw data by the user prior to InSAR processing. The two images must first be co-registered, using a correlation procedure to find the offset and difference in geometry between the two amplitude images. One SAR image is then re-sampled to match the geometry of the other, meaning each pixel represents the same ground area in both images. The interferogram is then formed by cross-multiplication of each pixel in the two images, and the interferometric phase due to the reference ellipsoid is removed, a process referred to as flattening. For deformation applications a DEM can be used in conjunction with the baseline data to simulate the contribution of the topography to the interferometric phase, this can then be removed from the interferogram.

Once the basic interferogram has been produced, it is commonly filtered using an adaptive power-spectrum filter to amplify the phase signal. For most quantitative applications the consecutive fringes present in the interferogram will then have to unwrapped, which involves interpolating over the 0 to 2π phase jumps to produce a continuous deformation field. At some point, before or after unwrapping, incoherent areas of the image may be masked out. The final processing stage involves geocoding the image, which involves resampling the interferogram from the acquisition geometry (related to direction of satellite path) into the desired geographic projection.

Software

[edit]A variety of InSAR processing packages are commonly used, several are available free for academic use.

- IMAGINE InSAR - commercial processing package embedded in ERDAS IMAGINE remote sensing software suite, code is C++ based. [1] homepage.

- ROI PAC - produced by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and CalTech. UNIX based, can be freely downloaded from The Open Channel Foundation.

- DORIS - processing suite from Delft University of Technology, code is C++ based, making it multi-platform portable. Distributed under GPL license from the DORIS homepage.

- Gamma Software - Commercial software suite consisting of different modules covering SAR data processing, SAR Interferometry, differential SAR Interferometry, and Interferometric Point Target Analysis, runs on Solaris, Linux, OSX, Windows, large discount for Research Institutes [2].

- Pulsar - Commercial software suite, UNIX based [3].

- DIAPASON - Originally developed by the French Space Agency CNES,[5][6] and maintained by Altamira Information, Commercial software suite - UNIX & Windows based [4].

Data Sources

[edit]

Early exploitation of satellite-based InSAR included use of Seasat data in the 1980s, but the potential of the technique was expanded in the 1990s, with the launch of ERS-1 (1991), JERS-1 (1992), RADARSAT-1 and ERS-2 (1995). These platforms provided the stable, well-defined orbits and short baselines necessary for InSAR. More recently, the 11-day NASA STS-99 mission in February 2000 used a SAR antenna mounted on the space shuttle to gather data for the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission. In 2002 ESA launched the ASAR instrument, designed as a successor to ERS, aboard Envisat. While the majority of InSAR to date has utilised the C-band sensors, recent missions such as the ALOS PALSAR and TerraSAR-X are expanding the available data in the L- and X-band.

Applications

[edit]Tectonic

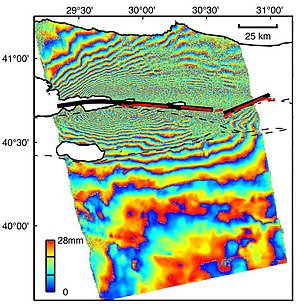

[edit]InSAR can be used to measure tectonic deformation, for example ground movements due to earthquakes. It was first used for the 1992 Landers earthquake,[5] but has since been utilised extensively for a wide variety of earthquakes all over the world. In particular the 1999 Izmit and 2003 Bam earthquakes were extensively studied.[7][8] InSAR can also be used to monitor creep and strain accumulation on faults.

Volcanic

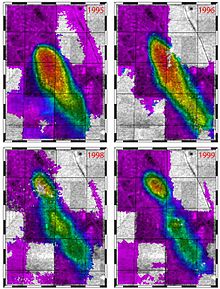

[edit]InSAR can be used in a variety of volcanic settings, including deformation associated with eruptions, inter-eruption strain caused by changes in magma distribution at depth, gravitational spreading of volcanic edifices, and volcano-tectonic deformation signals.[9] Early work on volcanic InSAR included studies on Mount Etna,[6] and Kilauea,[10] with many more volcanoes being studied as the field developed. The technique is now widely used for academic research into volcanic deformation, although its use as an operational monitoring technique for volcano observatories has been limited by issues such as orbital repeat times, lack of archived data, coherence and atmospheric errors.[11] Recently InSAR has also been used to study rifting processes in Ethiopia.[12]

Subsidence

[edit]

Ground subsidence from a variety of causes has been successfully measured using InSAR, in particular subsidence caused by oil or water extraction from underground reservoirs, subsurface mining and collapse of old mines. It can also be used for monitoring the stability of built structures, and landscape features such as landslides.[13]

DEM generation

[edit]

Interferograms can be used to produce digital elevation maps (DEMs) using the stereoscopic effect caused by slight differences in observation position between the two images. When using two images produced by the same sensor with a separation in time, it must be assumed other phase contributions (for example from deformation or atmospheric effects) are minimal. In 1995 the two ERS satellites flew in tandem with a one-day separation for this purpose. A second approach is to use two antennas mounted some distance apart on the same platform, and acquire the images at the same time, which ensures no atmospheric or deformation signals are present. This approach was followed by NASA's SRTM mission aboard the space shuttle in 2000. InSAR-derived DEMs can be used for later two-pass deformation studies, or for use in other geophysical applications.

Persistent Scatterer InSAR

[edit]Persistent or Permanent Scatterer techniques are a relatively recent development from conventional InSAR, and rely on studying pixels which remain coherent over a sequence of interferograms. Firstly, in 1999 Politecnico di Milano (POLIMI), Italy, developed a new multi-image approach, that took traditional interferometry a step further. This approach works by searching the stack of images for objects on the ground that provide a consistent and stable radar reflection back to the satellite. These objects could be the size of a pixel but, more likely, would be much smaller and contained within the pixel and, furthermore, are present in every image in the stack. POLIMI patented the technology in 1999 and registered two international trademarks: PSInSAR™ and POLIMI PS Technique™. PSInSAR™ refers to a specific algorithm developed and patented by POLIMI. POLIMI also created the spin-off company (Tele-Rilevamento Europa) in 2000 to commercialize the technology and perform ongoing research. As the result of the success of PSInSAR™, some research centres and other companies were inspired to develop their own algorithms which, like PSInSAR™, would overcome InSAR’s limitations. Today these techniques are collectively referred to as Persistent Scatterer Interferometry or PSI techniques, within scientific literature. The term Persistent Scatterer Interferometry (PSI) was created by ESA to define the second generation of radar interferometry techniques. Commonly such techniques are most useful in urban areas with lots of permanent structures, for example the PSI studies of European cities undertaken by the Terrafirma project.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ Massonnet, D.; Feigl, K. L. (1998), "Radar interferometry and its application to changes in the earth's surface", Rev. Geophys., vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 441–500

- ^ Burgmann, R.; Rosen, P.A.; Fielding, E.J. (2000), "Synthetic aperture radar interferometry to measure Earth's surface topography and its deformation", Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, vol. 28, pp. 169–209

- ^ Hanssen, Ramon F. (2001), Radar Interferometry: Data Interpretation and Error Analysis, Kluwer Academic, ISBN 9780792369455

- ^ Zebker, H.A.; Rosen, P.A.; Hensley, S. (1997), "Atmospheric effects in inteferometric synthetic aperture radar surface deformation and topographic maps", Journal of Geophysical Research, vol. 102, pp. 7547–7563

- ^ a b Massonnet, D.; Rossi, M.; Carmona, C.; Adragna, F.; Peltzer, G.; Feigl, K.; Rabaute, T. (1993), "The displacement field of the Landers earthquake mapped by radar interferometry", Nature, vol. 364, pp. 138–142

- ^ a b Massonnet, D.; Briole, P.; Arnaud, A. (1995), "Deflation of Mount Etna monitored by spaceborne radar interferometry", Nature, vol. 375, pp. 567–570

- ^ "Envisat's rainbow vision detects ground moving at pace fingernails grow". European Space Agency. August 6, 2004. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ^ "The Izmit Earthquake of 17 August 1999 in Turkey". European Space Agency. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ^ Wadge, G. (2003), "A strategy for the observation of volcanism on Earth from space", Phil. Trans. Royal Soc.Lond., vol. 361, pp. 145–156

- ^ Rosen, P. A.; Hensley, S.; Zebker, H. A.; Webb, F. H.; Fielding, E. J. (1996), "Surface deformation and coherence measurements of Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii, from SIR C radar interferometry", J. Geophys. Res., vol. 101, no. E10, pp. 23, 109–23, 126

- ^ Stevens, N.F.; Wadge, G. (2004), "Towards operational repeat-pass SAR interferometry at active volcanoes", Natural Hazards, vol. 33, pp. 47–76

- ^ Wright, T.J.; Ebinger, C.; Biggs, J.; Ayele, A.; Yirgu, G.; Keir, D.; Stork, A. (2006), "Magma-maintained rift segmentation at continental rupture in the 2005 Afar dyking episode" (PDF), Nature, vol. 442, pp. 291–294, doi:10.1038/nature04978

- ^ "Ground motion". European Space Agency. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ^ "Ground movement risks identified by Terrafirma". European Space Agendy. 8 September 2006. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- InSAR, a tool for measuring Earth's surface deformation Matthew E. Pritchard

- Radar interferometry tutorial

- USGS InSAR factsheet

- Remote monitoring of the earthquake cycle using satellite radar interferometry. Tim J. Wright, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A, 360, 2873-2888, 2002.