User:FredModulars/Florida

History

[edit]People, known as Paleo-Indians, entered Florida at least 14,000 years ago.[1] By the 16th century, the earliest time for which there is a historical record, major groups of people living in Florida included the Apalachee of the Florida Panhandle, the Timucua of northern and central Florida, the Ais of the central Atlantic coast, and the Calusa of southwest Florida, with many smaller groups throughout what is now Florida.[citation needed]

European arrival

[edit]

Florida was the first region of the continental United States to be visited and settled by Europeans. The earliest known European explorers came with the Spanish conquistador Juan Ponce de León. Ponce de León spotted and landed on the peninsula on April 2, 1513. He named it La Florida in recognition of the verdant landscape and because it was the Easter season, which the Spaniards called Pascua Florida (Festival of Flowers). The following day they came ashore to seek information and take possession of this new land.[2] The story that he was searching for the Fountain of Youth is mythical and appeared only long after his death.[3]

In May 1539, Conquistador Hernando de Soto skirted the coast of Florida, searching for a deep harbor to land. He described a thick wall of red mangroves spread mile after mile, some reaching as high as 70 feet (21 m), with intertwined and elevated roots making landing difficult.[4] The Spanish introduced Christianity, cattle, horses, sheep, the Castilian language, and more to Florida.[5] Spain established several settlements in Florida, with varying degrees of success. In 1559, Don Tristán de Luna y Arellano established a settlement at present-day Pensacola, making it the first attempted settlement in Florida, but it was mostly abandoned by 1561.

In 1564-65 there was a French settlement at Fort Caroline, in present Duval County, which was destroyed by the Spanish.[6]

In 1565, the settlement of St. Augustine (San Agustín) was established under the leadership of admiral and governor Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, creating what would become one of the oldest, continuously-occupied European settlements in the continental U.S. and establishing the first generation of Floridanos and the Government of Florida.[7] Spain maintained strategic control over the region by converting the local tribes to Christianity. The marriage between Luisa de Abrego, a free black domestic servant from Seville, and Miguel Rodríguez, a white Segovian, occurred in 1565 in St. Augustine. It is the first recorded Christian marriage in the continental United States.[8]

Some Spanish married or had unions with Pensacola, Creek or African women, both slave and free, and their descendants created a mixed-race population of mestizos and mulattos. The Spanish encouraged slaves from the Thirteen Colonies to come to Florida as a refuge, promising freedom in exchange for conversion to Catholicism. King Charles II of Spain issued a royal proclamation freeing all slaves who fled to Spanish Florida and accepted conversion and baptism. Most went to the area around St. Augustine, but escaped slaves also reached Pensacola. St. Augustine had mustered an all-black militia unit defending Spanish Florida as early as 1683.[9]

The geographical area of Spanish claims in La Florida diminished with the establishment of English settlements to the north and French claims to the west. English colonists and buccaneers launched several attacks on St. Augustine in the 17th and 18th centuries, razing the city and its cathedral to the ground several times. Spain built the Castillo de San Marcos in 1672 and Fort Matanzas in 1742 to defend Florida's capital city from attacks, and to maintain its strategic position in the defense of the Captaincy General of Cuba and the Spanish West Indies.

In 1738, the Spanish governor of Florida Manuel de Montiano established Fort Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose near St. Augustine, a fortified town for escaped slaves to whom Montiano granted citizenship and freedom in return for their service in the Florida militia, and which became the first free black settlement legally sanctioned in North America.[10][11]

In 1763, Spain traded Florida to the Kingdom of Great Britain for control of Havana, Cuba, which had been captured by the British during the Seven Years' War. The trade was done as part of the 1763 Treaty of Paris which ended the Seven Years' War. Spain was granted Louisiana from France due to their loss of Florida. A large portion of the Florida population left, taking along large portions of the remaining indigenous population with them to Cuba.[12] The British soon constructed the King's Road connecting St. Augustine to Georgia. The road crossed the St. Johns River at a narrow point called Wacca Pilatka, or the British name "Cow Ford", reflecting the fact that cattle were brought across the river there.[13][14][15]

The British divided and consolidated the Florida provinces (Las Floridas) into East Florida and West Florida, a division the Spanish government kept after the brief British period.[16] The British government gave land grants to officers and soldiers who had fought in the French and Indian War in order to encourage settlement. In order to induce settlers to move to Florida, reports of its natural wealth were published in England. A number of British settlers who were described as being "energetic and of good character" moved to Florida, mostly coming from South Carolina, Georgia and England. There was also a group of settlers who came from the colony of Bermuda. This would be the first permanent English-speaking population in what is now Duval County, Baker County, St. Johns County and Nassau County. The British constructed high-quality public roads and introduced the cultivation of sugar cane, indigo and fruits as well as the export of lumber.[17][18]

The British governors were directed to call general assemblies as soon as possible in order to make laws for the Floridas, and in the meantime they were, with the advice of councils, to establish courts. This was the first introduction of the English-derived legal system which Florida still has today, including trial by jury, habeas corpus and county-based government.[17][18] Neither East Florida nor West Florida sent any representatives to Philadelphia to draft the Declaration of Independence. Florida remained a Loyalist stronghold for the duration of the American Revolution.[19]

Spain regained both East and West Florida after Britain's defeat in the Revolutionary War and the subsequent Treaty of Versailles in 1783, and continued the provincial divisions until 1821.[20]

Statehood and Indian removal

[edit]

Defense of Florida's northern border with the United States was minor during the second Spanish period. The region became a haven for escaped slaves and a base for Indian attacks against U.S. territories, and the U.S. pressed Spain for reform.

Americans of English and Scots-Irish descent began moving into northern Florida from the backwoods of Georgia and South Carolina. Though technically not allowed by the Spanish authorities and the Floridan government, they were never able to effectively police the border region and the backwoods settlers from the United States would continue to immigrate into Florida unchecked. These migrants, mixing with the already present British settlers who had remained in Florida since the British period, would be the progenitors of the population known as Florida Crackers.[21]

These American settlers established a permanent foothold in the area and ignored Spanish authorities. The British settlers who had remained also resented Spanish rule, leading to a rebellion in 1810 and the establishment for ninety days of the so-called Free and Independent Republic of West Florida on September 23. After meetings beginning in June, rebels overcame the garrison at Baton Rouge (now in Louisiana), and unfurled the flag of the new republic: a single white star on a blue field. This flag would later become known as the "Bonnie Blue Flag".

In 1810, parts of West Florida were annexed by the proclamation of President James Madison, who claimed the region as part of the Louisiana Purchase. These parts were incorporated into the newly formed Territory of Orleans. The U.S. annexed the Mobile District of West Florida to the Mississippi Territory in 1812. Spain continued to dispute the area, though the United States gradually increased the area it occupied. In 1812, a group of settlers from Georgia, with de facto support from the U.S. federal government, attempted to overthrow the Floridan government in the province of East Florida. The settlers hoped to convince Floridians to join their cause and proclaim independence from Spain, but the settlers lost their tenuous support from the federal government and abandoned their cause by 1813.[22]

Seminoles based in East Florida began raiding Georgia settlements, and offering havens for runaway slaves. The United States Army led increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish territory, including the 1817–1818 campaign against the Seminole Indians by Andrew Jackson that became known as the First Seminole War. The United States now effectively controlled East Florida. Control was necessary according to Secretary of State John Quincy Adams because Florida had become "a derelict open to the occupancy of every enemy, civilized or savage, of the United States, and serving no other earthly purpose than as a post of annoyance to them."[23]

Florida had become a burden to Spain, which could not afford to send settlers or troops due to the devastation caused by the Peninsular War. Madrid, therefore, decided to cede the territory to the United States through the Adams–Onís Treaty, which took effect in 1821.[24] President James Monroe was authorized on March 3, 1821 to take possession of East Florida and West Florida for the United States and provide for initial governance.[25] Andrew Jackson, on behalf of the U.S. federal government, served as a military commissioner with the powers of governor of the newly acquired territory for a brief period.[26] On March 30, 1822, the U.S. Congress merged East Florida and part of West Florida into the Florida Territory.[27]

By the early 1800s, Indian removal was a significant issue throughout the southeastern U.S. and also in Florida. In 1830, the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act and as settlement increased, pressure grew on the U.S. government to remove the Indians from Florida. Seminoles offered sanctuary to blacks, and these became known as the Black Seminoles, and clashes between whites and Indians grew with the influx of new settlers. In 1832, the Treaty of Payne's Landing promised to the Seminoles lands west of the Mississippi River if they agreed to leave Florida. Many Seminole left at this time.

Some Seminoles remained, and the U.S. Army arrived in Florida, leading to the Second Seminole War (1835–1842). Following the war, approximately 3,000 Seminole and 800 Black Seminole were removed to Indian Territory. A few hundred Seminole remained in Florida in the Everglades.

On March 3, 1845, only one day before the end of President John Tyler's term in office, Florida became the 27th state,[28] admitted as a slave state and no longer a sanctuary for runaway slaves. Initially its population grew slowly.[29]

As European settlers continued to encroach on Seminole lands, the United States intervened to move the remaining Seminoles to the West. The Third Seminole War (1855–58) resulted in the forced removal of most of the remaining Seminoles, although hundreds of Seminole Indians remained in the Everglades.[30]

The first settlements and towns in South Florida were founded much later than those in the northern part of the state. The first permanent European settlers arrived in the early 19th century. People came from the Bahamas to South Florida and the Keys to hunt for treasure from the ships that ran aground on the treacherous Great Florida Reef. Some accepted Spanish land offers along the Miami River. At about the same time, the Seminole Indians arrived, along with a group of runaway slaves. The area was affected by the Second Seminole War, during which Major William S. Harney led several raids against the Indians. Most non-Indian residents were soldiers stationed at Fort Dallas. It was the most devastating Indian war in American history, causing almost a total loss of population in Miami.

After the Second Seminole War ended in 1842, William English re-established a plantation started by his uncle on the Miami River. He charted the "Village of Miami" on the south bank of the Miami River and sold several plots of land. In 1844, Miami became the county seat, and six years later a census reported there were ninety-six residents in the area.[31] The Third Seminole War was not as destructive as the second, but it slowed the settlement of southeast Florida. At the end of the war, a few of the soldiers stayed.

American Civil War

[edit]

American settlers began to establish cotton plantations in north Florida, which required numerous laborers, which they supplied by buying slaves in the domestic market. By 1860, Florida had only 140,424 people, of whom 44% were enslaved. There were fewer than 1,000 free African Americans before the American Civil War.[32]

On January 10, 1861, nearly all delegates in the Florida Legislature approved an ordinance of secession,[33][34] declaring Florida to be "a sovereign and independent nation"—an apparent reassertion to the preamble in Florida's Constitution of 1838, in which Florida agreed with Congress to be a "Free and Independent State." The ordinance declared Florida's secession from the Union, allowing it to become one of the founding members of the Confederate States.

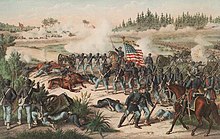

The Confederacy received little military help from Florida; the 15,000 troops it offered were generally sent elsewhere. Instead of troops and manufactured goods, Florida did provide salt and, more importantly, beef to feed the Confederate armies. This was particularly important after 1864, when the Confederacy lost control of the Mississippi River, thereby losing access to Texas beef.[35][36] The largest engagements in the state were the Battle of Olustee, on February 20, 1864, and the Battle of Natural Bridge, on March 6, 1865. Both were Confederate victories.[37] The war ended in 1865.

Reconstruction era through end of 19th century

[edit]Following the American Civil War, Florida's congressional representation was restored on June 25, 1868, albeit forcefully after Reconstruction and the installation of unelected government officials under the final authority of federal military commanders. After the Reconstruction period ended in 1876, white Democrats regained power in the state legislature. In 1885, they created a new constitution, followed by statutes through 1889 that disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites.[38]

In the pre-automobile era, railroads played a key role in the state's development, particularly in coastal areas. In 1883, the Pensacola and Atlantic Railroad connected Pensacola and the rest of the Panhandle to the rest of the state. In 1884 the South Florida Railroad (later absorbed by Atlantic Coast Line Railroad) opened full service to Tampa. In 1894 the Florida East Coast Railway reached West Palm Beach; in 1896 it reached Biscayne Bay near Miami. Numerous other railroads were built all over the interior of the state.

20th and 21st century

[edit]

Historically, Florida's economy has been based primarily upon agricultural products such as citrus fruits, strawberries, nuts, sugarcane and cattle.[39] The boll weevil devastated cotton crops during the early 20th century.

Until the mid-20th century, Florida was the least populous state in the southern United States. In 1900, its population was only 528,542, of whom nearly 44% were African American, the same proportion as before the Civil War.[40] Forty thousand blacks, roughly one-fifth of their 1900 population levels in Florida, left the state in the Great Migration. They left due to lynchings and racial violence, and for better opportunities in the North and the West.[41] Disfranchisement for most African Americans in the state persisted until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s gained federal legislation in 1965 to enforce protection of their constitutional suffrage.

In response to segregation in Florida, a number of protests occurred in Florida during the 1950s and 1960s as part of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1956–1957, students at Florida A&M University organized a bus boycott in Tallahassee to mimic the Montgomery bus boycott and succeeded in integrating the city's buses.[42] Students also held sit-ins in 1960 in protest of segregated seating at local lunch counters, and in 1964 an incident at St. Augustine motel pool, in which the owner poured acid into the water during a demonstration, influenced the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.[43]

Economic prosperity in the 1920s stimulated tourism to Florida and related development of hotels and resort communities. Combined with its sudden elevation in profile was the Florida land boom of the 1920s, which brought a brief period of intense land development. In 1925, the Seaboard Air Line broke the FEC's southeast Florida monopoly and extended its freight and passenger service to West Palm Beach; two years later it extended passenger service to Miami. Devastating hurricanes in 1926 and 1928, followed by the Great Depression, brought that period to a halt. Florida's economy did not fully recover until the military buildup for World War II.

In 1939, Florida was described as "still very largely an empty State."[44] Subsequently, the growing availability of air conditioning, the climate, and a low cost of living made the state a haven. Migration from the Rust Belt and the Northeast sharply increased Florida's population after 1945. In the 1960s, many refugees from Cuba fleeing Fidel Castro's communist regime arrived in Miami at the Freedom Tower, where the federal government used the facility to process, document and provide medical and dental services for the newcomers. As a result, the Freedom Tower was also called the "Ellis Island of the South."[45] In recent decades, more migrants have come for the jobs in a developing economy.

With a population of more than 18 million, according to the 2010 census, Florida is the most populous state in the southeastern United States and the third-most populous in the United States.[46] The population of Florida has boomed in recent years with the state being the recipient of the largest number of out-of-state movers in the country as of 2019.[47] Florida's growth has been widespread, as cities throughout the state have continued to see population growth.[48]

Florida was the site of the shooting of Trayvon Martin, a young black man killed by George Zimmerman in Sanford. The incident drew national attention to Florida's stand-your-ground laws, and it sparked African American activism nationally, including the Black Lives Matter movement.[49]

After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico in September 2017, a large population of Puerto Ricans began moving to Florida to escape the widespread destruction. Hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans arrived in Florida after Maria dissipated, with nearly half of them arriving in Orlando and large populations also moving to Tampa, Fort Lauderdale, and West Palm Beach.[50]

A handful of high-profile mass shootings have occurred in Florida in the twenty-first century. In June 2016, a gunman killed 49 people at a gay nightclub in Orlando. In February 2018, 17 people were killed in a school schooling at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, leading to new gun control regulations at both the state and federal level.[51]

On June 24, 2021, a condominium in Surfside, Miami collapsed, killing at least four people and leaving 99 people missing.[52]

- ^ Dunbar, James S. "The pre-Clovis occupation of Florida: The Page-Ladson and Wakulla Springs Lodge Data". Archived from the original on October 12, 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ^ Jonathan D. Steigman (September 25, 2005). La Florida Del Inca and the Struggle for Social Equality in Colonial Spanish America. University of Alabama Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8173-5257-8.

- ^ "Michael Francis: La historia entre Florida y España es de las más ricas de Estados Unidos". Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ Davidson, James West. After the Fact: The Art of Historical Detection Volume 1. Mc Graw Hill, New York 2010, Chapter 1, p. 7.

- ^ Proclamation, presented by Dennis O. Freytes, MPA, MHR, BBA, Chair/Facilitator, 500th Florida Discovery Council Round Table, VP NAUS SE Region; Chair Hispanic Achievers Grant Council

- ^ Hoffman, Paul E., 1943- (2004). A new Andalucia and a way to the Orient : the American Southeast during the sixteenth century. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 278. ISBN 0-8071-1552-5. OCLC 20594668.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Los Floridanos". Los Floridanos.

- ^ J. Michael Francis, PhD, Luisa de Abrego: Marriage, Bigamy, and the Spanish Inquisition, University of South Florida

- ^ Gene Allen Smith, Texas Christian University, Sanctuary in the Spanish Empire: An African American officer earns freedom in Florida, National Park Service

- ^ Pope, Sarah Dillard. "Aboard the Underground Railroad—Fort Mose Site". Nps.gov.

- ^ "Fort Mose Historical Society". Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ Florida Center for Instructional Technology. "Floripedia: Florida: As a British Colony". Fcit.usf.edu. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- ^ Wood, Wayne (1992). Jacksonville's Architectural Heritage. University Press of Florida. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8130-0953-7.

- ^ Beach, William Wallace (1877). The Indian Miscellany. J. Munsel. p. 125.

- ^ Wells, Judy (March 2, 2000). "City had humble beginnings on the banks of the St. Johns". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved July 2, 2011.

- ^ A History of Florida. Caroline Mays Brevard, Henry Eastman Bennett p. 77

- ^ a b A History of Florida. Caroline Mays Brevard, Henry Eastman Bennett

- ^ a b The Land Policy in British East Florida. Charles L. Mowat, 1940

- ^ Clark, James C.; "200 Quick Looks at Florida History" p. 20 ISBN 1561642002

- ^ "Transfer of Florida". fcit.usf.edu.

- ^ Ste Claire, Dana (2006). Cracker: Cracker Culture in Florida History. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-3028-9

- ^ "Florida's Early Constitutions—Florida Memory". Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ^ Alexander Deconde, A History of American Foreign Policy (1963) p. 127

- ^ Tebeau, Charlton W. (1971). A History of Florida. Coral Gables, Florida: University of Miami Press. pp. 114–118.

- ^ "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875". loc.gov. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Andrew Jackson". Florida Department of State. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875". loc.gov. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875". loc.gov. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ "Florida state population". population.us. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ Tindall, George Brown, and David Emory Shi. (edition unknown) America: A Narrative History. W. W. Norton & Company. 412. ISBN 978-0-393-96874-3

- ^ History of Miami-Dade county retrieved January 26, 2006 Archived January 10, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Historical Census Browser, Retrieved October 31, 2007 Archived August 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ordinance of Secession, 1861". Florida Memory. State Library & Archives of Florida. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- ^ "Florida Seceded! January 10, 1861|America's Story from America's Library". America's Library. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ Florida, State Library and Archives of. "Florida in the Civil War". Florida Memory. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ Taylor, R. (1988). Rebel Beef: Florida Cattle and the Confederate Army, 1862-1864. The Florida Historical Quarterly, 67(1), 15-31. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/30147921

- ^ Taylor, Paul. (2012) Discovering the Civil War in Florida: A Reader and Guide (2nd edition). pp. 3–4, 59, 127. Sarasota, Fl.: Pineapple Press.

- ^ Nancy A. Hewitt (2001). Southern Discomfort: Women's Activism in Tampa, Florida, 1880s–1920s. University of Illinois Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-252-02682-9.

- ^ "Florida Agriculture Overview and Statistics - Florida Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services". www.fdacs.gov.

- ^ Historical Census Browser, 1900 Federal Census, University of Virginia [1] [dead link]. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ^ Rogers, Maxine D.; Rivers, Larry E.; Colburn, David R.; Dye, R. Tom & Rogers, William W. (December 1993), "Documented History of the Incident Which Occurred at Rosewood, Florida in January 1923" Archived May 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, p. 5. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ^ "The Tallahassee Bus Boycott 1956-57". Florida Memory. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "The Civil Rights Movement in Florida". Florida Memory. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project (1939). Florida. A Guide to the Southernmost State. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 7.

- ^ "Freedom Tower—American Latino Heritage: A Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary". Nps.gov.

- ^ Munzenrieder, Kyle (December 23, 2014). "Florida Is Now Officially the Third Most Populous State". Miaminewtimes.com.

- ^ Lea, Brittany De (August 9, 2019). "Florida to see population boom over coming years as SALT deductions remain capped". FOXBusiness.

- ^ Millsap, Adam. "Florida's Population Is Booming--But Should We Worry About Income Growth?". Forbes.

- ^ CNN, By Nicole Chavez (5 December 2019). "George Zimmerman lawsuit reminds us of how significant the Trayvon Martin case was for a divided country". CNN Digital. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

{{cite web}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ "A Great Migration From Puerto Rico Is Set to Transform Orlando". The New York Times. November 17, 2017.

- ^ Andone, Dakin. "Parkland students turned from victims to activists and inspired a wave of new gun safety laws". CNN. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ CNN, By <a href="/profiles/aditi-sandal">Aditi Sangal</a>, <a href="/profiles/meg-wagner">Meg Wagner</a>, Melissa Macaya, <a href="/profiles/veronica-rocha">Veronica Rocha</a> and <a href="/profiles/fernando-alfonso-iii">Fernando Alfonso III</a> (2021-06-24). "51 people assumed to be living in collapsed building are not accounted for, commissioner says". CNN. Retrieved 2021-06-24.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)