User:Egm4313.s12/Nguyen Ngoc Bich essay

NOTE: The Essay version 22:36, 29 March 2023 of the Draft:Nguyen_Ngoc_Bich is preserved here below. Egm4313.s12 (talk) 22:47, 29 March 2023 (UTC)

Nguyen Ngoc Bich | |

|---|---|

| Born | 18 May 1911 |

| Died | 4 Dec 1966 |

| Nationality | Vietnamese |

| Citizenship | South Vietnam |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1935 - 1966 |

| Known for | Resistance war, politics |

| Title | Doctor (medical) |

| Signature | |

| |

Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911–1966) was an engineer, a hero in the Vietnamese resistance against the French colonists,[1][a] a medical doctor, an intellectual and politician, who proposed an alternative viewpoint to avoid the high-casualty, high-cost war between North Vietnam and South Vietnam.[2]

The Nguyen-Ngoc-Bich street in the city of Cần Thơ, Vietnam, was named after him to honor and commemorate his feats (of sabotaging bridges to slow down the colonial French-army advances) and heroism (imprisoned, subjected to an "intensive and unpleasant interrogation" that left a mark on his forehead,[b] and exiled) during the (French) First Indochina War.

Upon graduating from the École polytechnique (engineering military school under the Ministry of Armies) and then from the École nationale des ponts et chaussées (civil engineering) in France in 1935,[3] Dr. Bich returned to Vietnam to work for the French colonial government. After World War II, he became a senior commander in the Vietnamese resistance movement, and insisted on fighting for Vietnam's independence, not for communism.

Suspecting being betrayed by his side and apprehended by the French forces, he was saved from execution by a campaign for amnesty by his Polytechnique classmates based in Vietnam, mostly high-level officers of the French army, and was subsequently exiled to France, where he founded with friends and managed the Vietnamese publishing house Minh Tan (in Paris), which published many important works for the Vietnamese literature.[c] In parallel, he studied medicine and became a medical doctor. He was highly regarded in Vietnamese politics, and was considered "by many"[5][d][e] as an alternative to Ngo Dinh Diem as president of South Vietnam. His candidature for the 1961 presidential election in opposition to Diem was, however, declared invalid by the Saigon authorities at the last moment for "technical reasons".[5][3]

Much of the information in this article came from the document Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911-1966): A Biography.[4]

Hero of the resistance

[edit]Ellen J. Hammer was the first American-born historian with a deep knowledge of the French colonial rule in Indochina in the early 1950s during the First Indochina War. Dr. Hammer’s[6][f] highly influential book titled The Struggle for Indochina[7][g]—published in 1954 well before the United States sent American troops to Vietnam in the 1960s—described the events, politics, and historic personalities leading to the First Indochina War. Her works were considered among the must-read books by respected historians on Vietnam history, as Osborne (1967)[9] wrote: “Indeed, any serious student of Viet-Nam will have either read Devillers[h], Lacouture, Fall, Hammer and Lancaster[10][i]'s studies already, or will be better served by reading them first hand.” To give a historical context within which Dr. Bich fought the French colonists, there is no better English source to begin than Dr. Hammer’s book. First, regarding the American dilemma (1-To help the French to re-establish its colony in Vietnam or 2-To help free the Vietnamese from the yoke of French colonialism), Hammer wrote:

The United States has entangled itself in a war in a distant corner of Asia in which it resolutely does not want to participate and from which it equally resolutely cannot abstain. It has committed itself to the cause of France [ French Indochina ] and of Bao Dai, but enough of the old spirit of anticolonialism is left to make this a somewhat unsavory commitment: it cannot bring itself wholly to ignore the fact that the free world looks less than free to a people whose country is being fought over by a foreign army. Aware that a lasting peace can be built only on satisfaction of the national aspirations of the Indochinese, the United States must at the same time conciliate a France reluctant to abandon her colonial past.

The situation in Tonkin (North Vietnam) in March 1946 was as follows:

There were some 185,000 Chinese soldiers north of the sixteenth parallel and some 30,000 Japanese, many of them still in possession of their arms. All the French troops in the north were disarmed and held prisoner in the Hanoi Citadel, where the Japanese had left them; there were also some 25,000 Frenchmen living in Hanoi. Only 15,000 French troops were in Saigon and they had to travel several days to get to Haiphong before they could go to Hanoi.

Yet, the French hawkish colonists in Cochinchina (South Vietnam)—led by the "warmonger" triumvirate "High Commissioner Admiral Georges Thierry d’Argenlieu, Supreme Commander General Jean-Etienne Valluy, and Federal Commissioner of Political Affairs Léon Pignon"[11][j]—took a "gigantic gamble in dispatching an invasion force to the port city of Haiphong,"[11] fell into the "Chinese trap,"[11] in which the Chinese with a superior army forced both the French and the Vietnamese to sign the March 6 Agreement,[k] which "was simply an armistice that provided a transient illusion of agreement where actually no agreement existed."[7], p.157 Indeed, after a short period following a "modus vivendi," the First Indochina War started on 1946 December 19.[11][l]

Between March 6 and December 19, in Cochinchina, the military situation did not favor the Vietnamese:

Outside Saigon the various nationalist resistance groups, weakened though they were by the months of warfare with the British and French, still controlled large sections of the Cochin Chinese countryside. Ho Chi Minh proposed to General Leclerc the sending of mixed Franco-Vietnamese commissions to establish peace in Cochin China after the signing of the March 6 accord, but the General saw no reason for this in what was supposed to be French territory. When Ho sent his own emissaries to the south, they were arrested by the French who continued to regard Cochin China as a French colony, claiming a free hand there until the referendum could be held. This led to difficult local problems, as in the case of the Vietnamese emissary sent by one Vietnamese zone commander [Nguyen Ngoc Bich] to discuss a cease-fire with the local French commanding officer. The emissary was unceremoniously informed that the French expected complete capitulation—the surrender of arms and prisoners—and that this was an ultimatum. They had until the 31st of March to comply; if they failed to do so, the fighting would begin again. Before the Vietnamese left French headquarters, the French officer took his name and it was soon public knowledge that the French had put a price on his head as well as on that of his commander, Nguyen Ngoc Bich. In this particular region of Cochin China fighting resumed by the end of the month.

Chester L. Cooper was an American diplomat and a key negotiator in many critical agreements in the 1950's and 60's, beginning with his involvement in the Geneva Conference on Indochina in 1954.[12] In his 2005 memoir In the Shadows of History: 50 Years Behind the Scenes of Cold War Diplomacy, "he recounted his association with a constellation of historic figures that included John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Nikita S. Khrushchev and Ho Chi Minh".[12][m] Dr. Cooper[n]—who acquired a deep knowledge of Vietnam history from his years in Asia, from 1941 to 1954, first working for the Office of Strategic Services[o] in China, then for the CIA in 1947, and subsequently became head of the Far East staff of the Office of National Estimates in 1950[13]—devoted some three to four pages to describe Dr. Bich in his Vietnam-history book The Lost Crusade: America in Vietnam, in particular some aspects of Bich's resistance activities:

As commander of the Viet Minh forces in the Delta during the late 40s, Bich became one of the most popular local heroes. During 1946 the Viet Minh hierarchy became concerned that Bich might pose a threat to the aims of the Viet Minh in the southern part of Vietnam, and by the end of that year Ho apparently decided that Bich had served his purpose in the Delta. He was “invited” to move North to become a member of the Viet Minh political and military headquarters in Hanoi. Bich was reluctant to leave his command, not only because of his desire to continue the fight against the French, but also because he felt uneasy about leaving his base of power. Nonetheless, he made his way north via the nationalist underground to Hanoi.

A day or two before Bich was to report to the Viet Minh headquarters, the French discovered his hiding place near Hanoi. Since he was on the French "most wanted" list, he was subjected to an intensive and unpleasant interrogation.[b]

Joseph A. Buttinger was a Nazi fighter, an ardent advocate for refugees of persecution, and a "renowned authority on Vietnam and the American war" in that country.[15] In 1940, he helped founded the International Rescue Committee, "a nonprofit organization aiding refugees of political, religious and racial persecution," and while "working with refugees in Vietnam in the 1950s, he became immersed in the history, culture, and politics of that nation."[15] His scholarship was in high demand during the Vietnam War. The New York Times described his his two-volume Vietnam-history book, Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled,[16][1][p] as "a monumental work" that "marks a strategic breakthrough in the serious study of Vietnamese politics in America" and as "the most thorough, informative and, over all, the most impressive book on Vietnam yet published in America."[15] Joseph Buttinger wrote in Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled, Vol. 2 that Dr. Bich was "the resistance hero" whom "Diem had no success" to convince to join his cabinet:

Diem left Paris for Saigon on June 24, accompanied by his brother Luyen, by Tran Chanh Thanh, and by Nguyen Van Thoai, a relative of the Ngo family and the only prominent exile willing to join Diem's Cabinet. With others, such as the resistance hero Nguyen Ngoc Bich, Diem had no success. He tried unsuccessfully to win Nguyen Manh Ha, a Catholic who had been Ho Chi Minh's first Minister of Economics but who had parted with the Vietminh in December, 1946. These men, and others too, rejected Diem's concept of government, which clearly aimed at a one-man rule. Nor did they share Diem's illusions about the chances of preventing a Geneva settlement favorable to the Vietminh. Diem apparently believed that the National Army, no longer fighting under the French but for an independent government, would quickly become effective and reduce the gains made by the Vietminh.

That Nguyen Ngoc Bich was being hunted by the French colonists was described in Joseph Buttinger's book:

[Note] 9. Miss Hammer cites the case of an emissary sent by Nguyen Ngoc Bich. The French took down his name when he came to their headquarters to negotiate a cease-fire, and "it was soon public knowledge that the French had put a price on his head as well as on that of his commander, Nguyen Ngoc Bich" (ibid., p. 158).

Respected intellectual and politician

[edit]In 1962, as an intellectual in exile in Paris, Dr. Bich published an article, among respected historians at the time such as Philippe Devillers, Bernard B. Fall, Hoang Van Chi etc.,[5] presenting an incisive analysis of the economics and politics of the two Vietnams, and proposed an alternative viewpoint to avoid the Second Indochina War; see Section Peaceful negotiation, an independent viewpoint, where a summary of his article is provided.

Chester L. Cooper described Dr. Bich as one among some "genuine nationalists" living in exile in France in the 1950s:[14]

One such patriot was Dr. Nguyen Nhoc Bich. By profession Bich had been an engineer—a graduate of France's prestigious Ecole Polytechnique. He was a consequential and revered figure. His father was one of the founders of a branch of the Cao Dai sect, and his family had long been highly respected in the southern part of Vietnam, particularly in the area of Ben Tre Province. Bich had joined the Viet Minh because he was convinced there was a chance for non-Communist nationalists to band together with the Communists in a broad coalition to establish a genuinely free and independent Vietnam. Bich, as well as many other educated, non-Communist nationalists, was influenced by the French political tactic of alliances between moderate and Communist groups to achieve short-range objectives. The problem in Vietnam, however, was that the non-Communist nationalists had no significant political base of their own and were either swallowed up or destroyed by the Viet Minh's well-organized, politically aggressive Communist leadership.

In Paris, Dr. Bich was a "most popular oppositionst" to Ngo Dinh Diem and his regime, as described in Joseph Buttinger's book:

[Note] 92. [Robert] Scigliano[17] mentions [Nguyen Bao Toan] and Nguyen Ngoc Bich as "perhaps the two most popular of the Paris oppositionists (op. cit., pp. 23-24, 79-80, and 82)."

The French suggested Dr. Bich as a serious alternative to Ngo Dinh Diem as Prime Minister of South Vietnam under Bao Dai:

Diem was not the only candidate for prime minister under Bao Dai, and the French considered him hostile to their business interests, which they expected to survive the change in government. The names the French put forward could be dismissed as collaborators, however, and the one serious alternative to Diem, Dr. Nguyen Ngoc Bich, had his own liabilities. Although not a Communist himself, Bich had fought with the Vietminh, and his father was prominent in the Cao Dai, an eclectic sect that revered Confucius, Buddha, Jesus, Joan of Arc and Victor Hugo. Despite a medical degree, Bich could seem so mystical that Diem looked hard-headed and practical to the Vietnamese colony in Paris and to Foster Dulles, who saw that he would be dependably anti-Communist.

Early life and education

[edit]Engineer and doctor Nguyen Ngoc Bich was born on 18 May 1911[r] in An Hoi village, Bao Huu canton, Bao An district, now in Giong Mong district, Ben Tre province. He was the son of Mr. Nguyen Ngoc Tuong (1881-1951), Cao Dai Ban Chinh Dao (Ben Tre), and Ms. Bui Thi Giau.

As a child, he stayed with his father, lived in many places such as Can Tho, Ha Tien, Can Giuoc and mainly studied in Can Giuoc. In 1926, at the age of 15, he went to Saigon to study and graduated with a Baccalaureat at Chasseloup Laubat French School with very high scores, studying abroad in France. In France, he studied and obtained engineering degrees from the École Polytechnique in Paris (he entered in 1931 and graduated in 1933) and later from the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées also in Paris. These are 2 prestigious engineering universities in France, as well as in the world so far, especially Polytechnique because the entrance exam is very difficult and is a military school under the tutelage of the French Ministry of the Army, students when graduating have the rank of a military officer and at that time had to work for the government (civil or military) for a period of time.

Resistance fighter and prison time

[edit]After graduating from the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, a civil engineering school, he returned home to work as a civil engineer for the colonial government at the Soc Trang Irrigation Department until the Japanese coup d'état in Viet Nam (09/03/1945). He joined the Resistance in the Soc Trang base area and was appointed deputy of the 9th Zone and a Member of Parliament for Rach Gia in the first National Assembly (term 1945-1960) of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. He destroyed many bridges that were notoriously difficult to break such as Cai Rang Bridge in Can Tho,[19][s] where a street was named after him, Nhu Gia Bridge in Soc Trang, etc., blocking the French advance of General Leclerc's Generals Valluy and Nyo.

In 1946, a French army patrol arrested him in An Phu Dong near Saigon in a house where he was waiting for a guide to escort him to Da Lat for the Viet Nam-France Preliminary Conference (April and May 1946)[t] in preparation for the Fontainebleau Conference to take place in France (July to September 1946). He was tortured but still hid his real name and profession, until a French colonel who was inspecting the area where he was captured, hearing that he seemed to be more than just a teacher, revealed to him that he graduated from Polytechnique and was looking for a man named Nguyen Ngoc Bich who graduated from the same school. That colonel took him back to be locked up in Saigon, less dangerous. He was sentenced to death by the Military Court because he graduated from École Polytechnique and was a French army officer. Hoang Xuan Han, minister of education and fine arts in Tran Trong Kim's cabinet (17-04-1945), also a graduate of Polytechnique (he entered in 1930), wrote a letter to the alumni of this engineering school urging them to understand Nguyen Ngoc Bich's patriotism and help him in his difficult times.[3] French military officers in Vietnam graduated from Polytechnique, based on the Franco-Vietnamese agreement of March 9, 1946, to put Nguyen Ngoc Bich's name on a prisoner exchange list and organize his exile in France.[3]

Life in exile in France

[edit]

Back in France, he lived with Dr Henriette Bui Quang Chieu, Vietnam's first female doctor, but the two did not marry because they were relatives (his mother, Bui Thi Giau, was a cousin of Bui Quang Chieu, Henriette Bui's father). Back in France, he founded in Paris Minh Tan[22] publishing house ((agents in Vietnam were the two bookstores Truong Thi (Hanoi) and Bich Van Thu Xa (Saigon)) with some friends to publish works of Vietnamese intellectuals to help improve people’s knowledge living in Vietnam.

Published books include such as Dao Duy Anh's “Hán-Việt Tự Điển” (Chinese-Vietnamese dictionary) and “Pháp-Việt Tự Điển” (French-Vietnamese dictionary), "French-Vietnamese Scientific Nouns", Hoang Xuan Han's “Danh từ khoa học Pháp-Việt” (Scientific vocabulary French-Vietnamese), “Chinh Phụ ngăm bị khảo” and “La sơn Phu tử”, Tran Duc Thao's "Phénoménologie et matérialisme dialectique" (Phenomenology and Dialectical Materialism), doctors Pham Khac Quan and Le Khac Thien’s “Danh tử Pháp Việt về thuật ngữ kỹ thuật trong y tế” (French Vietnamese vocabulary on technical terminology in medicine), etc. After graduating from medicine and receiving a doctor's degree, he studied cancer and taught Medical Physics at the Paris Medical School until his death. After he finished composing his Agrégation thesis ("agrégation" (translated into Thạc Sĩ in Vietnamese) is a degree higher than PHD), he could not take the exam because foreigners who want to be enrolled in the exam, must provide a letter of recommendation from their Embassy, at that time the Embassy of the State of Viet Nam with which he refused to have any link. During the French colonial period, French citizenship was given with parsimony to the ones who rendered great service to France and who applied for it. He did not render any service to France, he just had to work as a civil engineer for the colonial government, which was mandatory because he graduated from Ecole Polytechnique.

Engagement in politics in South Vietnam

[edit]In 1954, before Diem was selected by Bao Dai, according to the books Our Vietnam: The War 1954-1975 by Arthur John Langguth[u] and The Lost Crusade – America in Vietnam by Chester L. Cooper,[v] he was widely regarded as a possible prime minister of the State of Vietnam.

Along with some Vietnamese in France, he wanted to give the country another way than the one of war: cooperation between North and South that help each other develop to catch up with neighbouring countries and avoid dependence on foreign states: negotiations and economic and trade cooperation while waiting for favourable conditions for the two sides to unite the country. That idea was echoed by him in an article he wrote in the quarterly magazine China Quarterly, March 3-5, 1962. Later, the same idea was proposed by Ho Chi Minh (in 1958 and 1962)[w] and Ngo Dinh Diem and Ngo Dinh Nhu[x] (in 1963) but without success. A member of his group went to Geneva (Geneva Conference in 1954) to meet Phan Van Dong. He was invited by Georges Bidault, French Foreign Minister (until June 16, 1954) to meet and an American professor from Washington came to Paris to see him. But at that time the U.S. policy was to eliminate communism, and Pham Van Dong's side paid attention to the planned reunification elections in 1956. That group of Vietnamese intellectuals—most of whom were professionals trained and residing in France—kept to be discreet at that time and often met at the headquarters of Minh Tan publishing house, which made them called by some the Minh Tan group. The publisher's logo is a pigeon sandwiched in the beak of an olive branch, symbolizing "Peace".

He sent his candidacy for the 1961 South Viet Nam presidential election, with his partner Nguyễn Văn Thoại,[y] a professor at Collège de France in Paris and a former minister of Ngô Đình Diệm. But his file was dismissed by the Ngo Dinh Diem government because of "technical problems".

Cancer and end of life, return to Vietnam

[edit]Suffering from throat cancer, he returned to Vietnam in 1966 when he was very severe and died in Thu Duc on 4 Dec 1966.[r] He was buried in Ben Tre, near the grave of his father Nguyen Ngoc Tuong and his brothers, including his brother martyr Nguyen Ngoc Nhut,[21][z] who was a member of the Southern Administrative Resistance Committee. But the grave is open because Nhut's remains have been moved by the government to a martyr's graveyard in Ben Tre.

Peaceful negotiation, an independent viewpoint

[edit]Vietnam-War casualties

[edit]How many people died in the Vietnam War? Britannica (accessed on 2023.02.18)

Written and fact-checked by The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

| In 1995 Vietnam released its official estimate of the number of people killed during the Vietnam War: as many as 2,000,000 civilians on both sides and some 1,100,000 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong fighters. The U.S. military has estimated that between 200,000 and 250,000 South Vietnamese soldiers died. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., lists more than 58,300 names of members of the U.S. armed forces who were killed or went missing in action. Among other countries that fought for South Vietnam, South Korea had more than 4,000 dead, Thailand about 350, Australia more than 500, and New Zealand some three dozen. |

The China Quarterly, Vol. 9, Mar 1962

[edit]The China Quarterly | Cambridge Core

| The China Quarterly is the leading scholarly journal in its field, covering all aspects of contemporary China including Taiwan. Its interdisciplinary approach covers a range of subjects including anthropology/sociology, literature and the arts, business/economics, geography, history, international affairs, law, and politics. Edited to rigorous standards by scholars of the highest repute, the journal publishes high-quality, authoritative research. International in scholarship, The China Quarterly provides readers with historical perspectives, in-depth analyses, and a deeper understanding of China and Chinese culture. In addition to major articles and research reports, each issue contains a comprehensive Book Review section. |

The China Quarterly: Volume 9 - | Cambridge Core (Mar 1962)

Contributors

[edit]Vietnam—An Independent Viewpoint

[edit]Nguyen-Ngoc-Bich (1962), Vietnam—An Independent Viewpoint The China Quarterly, Volume 9, March, pp. 105-111. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S030574100002525X

Summary of main points

[edit]In 1962, Dr. Bich[2] laid out an argument to avoid the subversion war by North Vietnam to conquer rice from South Vietnam to solve its famine problem due to low yields in agricultural production using archaic methods and due to the failed agrarian reform. His main points were (1) South Vietnam should have a truly liberal democratic government, (2) the South should establish commercial relations with the North to help solve the said famine problem, (3) the South should maintain a non-aligned neutrality that would prevent interference from the North, (4) the South would peacefully negotiate with the North toward a progressive reunification. Below is a more detailed summary of his article, looking back from more than 60 years later. As a result, past tense is used in this summary to describe long-past events, instead of the sometimes present tense used in the original article.[4] The full article translated into French is available in the document Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911-1966): A Biography.[4]

| Contrary to the belief of the Western world (that the Vietnamese generally disliked, and had an inferiority complex against, the Chinese), the Vietnamese tended to be too proud of their history and victories against the Chinese and Mongol invaders over the centuries.

Aware of the Chinese historical “fierce expansionism,” an important question for North and South Vietnam was how to safeguard the future of Vietnam as a whole country. While South Vietnam tried to forcibly assimilate Chinese immigrants and their descendants, North Vietnam adopted a “more subtle attitude”, moving from “fears” during the Chiang Kai-shek era to “solidarity and friendship” after the communist had won in 1949. The Geneva agreements, while satisfying for China, left the North Vietnamese to be content with the prospect of reunifying with South Vietnam upon an election. After the failure of the agrarian reform, there was a concern of the presence of many Chinese soldiers and civilians in North Vietnam. To keep Chinese economic aid flowing, Ho Chi Minh initially maintained a balance between Peking (Beijing) and Moscow, but subsequently tilted toward Moscow after Peking admitted that it could not help carry out a semi-heavy industrialization. In September 1960, Le Duan, then Secretary-General of the Party, put forward a three-point program: (1) Support Moscow in any Sino-Soviet dispute, (2) Five-year plan (1961-1965) to socialize North Vietnam, (3) Progressive and peaceful reunification of the two Vietnams. With the nomination of Le Duan—who led the struggle for independence in South Vietnam for a long time and knew the South more than anyone else—as First Secretary of the Party, North Vietnam began to undertake the reconquest of the South, with the first step being to eliminate the Ngo Dinh Diem regime and the American influence in the South. There were deeper motives. “The most striking feature of the Vietnamese Communist leadership was its outstanding spirit of realism, even pragmatism.” They continuously and critically reexamined facts so that a lesson could be drawn for every action and every happening to avoid past mistakes. By doing so, they tended to imitate or to repeat past actions that were proven successful, and lacked imagination and open-mindedness to create new solutions to tackle new challenges.   For example, they stopped following the advice of Chinese tacticians in launching large-scale mass attacks once many of their soldiers died by French napalm bombs. They switched from the costlier manufacturing of arms to the less expensive manufacturing of hand grenades, which can be used against light battalions to seize their arms. They bred dogs, instead of pigs, as a source of meat since dogs produced two litters of young each year, while pigs produced only one. A deeper motive to swing closer to Moscow was to develop a rapid industrialization to raise the standard of living to avoid complaints about dictatorship and restriction of freedom, and also the “dreaded spectre of becoming a mere satellite state”. The targets of the Five-Year Plan were “extremely optimistic”. In the old French Indochina, “great leaps forward” in economics were achieved in some sectors, such as a 400% increase in plantation area, 150% increase in the number of workers in industrial establishments, in spite of World War I. Now, there was an abundance of labor due to high unemployment. The planned industrial projects could be completed if foreign aid maintained the same rhythm and agricultural production was adequate. It was doubtful, however, that the target of growing agricultural production by 61% over five years could be achieved due to low yields resulting from the archaic methods of cultivation, the old system of sub-letting land, the difficulty of cultivating new land, the discontent among the peasants, and the disastrous agrarian reforms and its consequence. Hunger had become endemic, and China could not come to the rescue because of her own problems. Rice had to be smuggled from the South to the North.  The five-year plan ran a “grave risk of failure” due to lack of food to feed the people in North Vietnam, without an increase in rice supply from South Vietnam, not to mention other unpredictable factors such as floods, droughts, bad weather, etc. The success of the Five-Year Plan would be a primary condition to maintain some independence from Peking, which would exert a greater influence than from Moscow in the case of “necessary and inevitable war,” and the North being a satellite of China “would constitute a most serious menace for the South, particularly in time of any major crisis.” The reconquest of the South entrusted to Le Duan could then be understood as “a struggle unleashed simply for the purpose of conquering rice”, without which the five-year plan most certainly would fail. For many Southerners, their reaction against the Diem regime, rather than the love for Communism, enabled this subversion war to continue. The enormous economic benefit that North Vietnam would harvest from the national reunification was the primary reason for the war. North Vietnam was fighting to secure rice, and thus the war was, from the purely national point of view, a legitimate one. Ngo Dinh Diem on the other hand refused to provide aid to alleviate the famine in the North. The Vietnamese people had for a long time a desire to have a liberal, truly democratic government. and had proven that in the end they would rise time and again to thwart the yoke imposed on them by any foreign power. To avoid such internal war for rice from becoming a proxy war for Moscow, there should be a liberal regime in Saigon that allowed for establishing commercial relations with Hanoi and for a call to stop the fighting. Moreover, a non-aligned political neutrality would prevent interference by North Vietnam in the affairs of South Vietnam. A peaceful and progressive reunification of the two Vietnams could only be achieved through negotiation at a table, and not by arm struggle in the jungle. The South would hope to live side by side peacefully with the North to collaborate in building the common Vietnamese nation, as the alternative would make “reunification” a propaganda that concealed the desire to conquer. |

Notes

[edit]- ^ See the quotations from Vietnam history books by renowned scholars in Section Hero of the resistance.

- ^ a b A photo showing the injury mark on the forefront of Dr. Bich as a result of this "intensive and unpleasant interrogation" (Section Hero of the resistance) can be found in the document Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911-1966): A Biography.[4]

- ^ A list of important books published by Minh Tan can be found in the document Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911-1966): A Biography.[4]

- ^ A direct quote from the brief introduction of the contributors to The China Quarterly, Volume 9[5], 1962, reads: Dr. Bich's "personal influence upon Cochin Chinese opinion is considerable, and he is regarded by many as a possible successor to President Ngo Dinh Diem".

- ^ The Editorial of The China Quarterly, Volume 9, reads: "Five of our articles are by specialists who have observed the Hanoi regime from a distance. M. Tongas and Mr. Hoang Van Chi are writing on the basis of personal experience. Dr. Bich presents an independent view of the whole Vietnamese situation."

- ^ Ellen Hammer received her PhD from Columbia University, where she specialized in international relations, with a dissertation on public law and government.[6] A summary of an obituary for Ellen J. Hammer is in the document Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911-1966): A Biography.[4]

- ^ Ellen Hammer's 1954 book The Struggle for Indochina[7] was "A superb study of the French effort to hold on to Indochina."[8]

- ^ See French Cochinchina, Ref. 40: Philippe Devillers, Histoire du Viêt-Nam de 1940 à 1952, Seuil, 1952, and Philippe Devillers (1920-2016), un secret nommé Viêt-Nam, Mémoires d'Indochine, Internet archived 2022.06.29.

- ^ Donald Lancaster's 1961 book The Emancipation of French Indochina[10] was "The best single book on the history of all Indochina to about 1955."[8]

- ^ "The main warmongers, who must bear the brunt of the responsibility, not only for the seizure of Haiphong in November, but also for the outbreak in Hanoi, were a French triumvirate in Saigon..."[11], pp.5-6

- ^ "Arriving at Haiphong in the morning of March 6, the French fleet sailed right into a Chinese trap. The French thought they had secured Chinese support for disembarking troops in the north in a treaty signed in Chongqing on February 28, but Chiang Kai-shek’s government fooled them. When the French ships approached Haiphong harbor, the Chinese stood ready to resist the French onslaught and actually fired at the ships. Meanwhile, the Chinese were pressuring both the Vietnamese government and a French team of negotiators in Hanoi to sign a deal on behalf of their two nations. Neither the French nor the DRV could afford an open confrontation with China."[11], p.5

- ^ There are several different interpretations by respected historians (such as Fall, Hammer, Devillers, and Tønnesson) on how the First Indochina War started on 1946 December 19.[11], p.5 and Note 10 on p.262

- ^ A summary of an obituary for Chester L. Cooper is in the document Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911-1966): A Biography.[4]

- ^ Chester L. Cooper undertook his doctoral study in urban land economics, and after an interruption due to WWII, received his PhD in 1960.[13]

- ^ For the relationship between the OSS and Ho Chi Minh during WWII, see OSS Deer Team.

- ^ a b c Osborne (1967), a Vietnam scholar, provided a critical review[9] of Joseph Buttinger's two-volume book.[16][1] A recent summary of Joseph Buttinger's book was provided by Stefania Dzhanamova on 2021 Aug 11 on Goodreads.

- ^ See Joseph Buttinger's book, Vol. 1,[16] p. 641.

- ^ a b The exact dates of birth and of death of Dr. Bich, together with the locations, are inscribed in a commemoration stela for both Dr. Henriette Bui and Dr. Bich in a Cao Dai cemetery in Ben Tre, Vietnam. A photo of this stela is provided in Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911-1966): A Biography.[4]

- ^ A street in Can Tho is named Nguyen Ngoc Bich to commemorate him blowing up the Cai Rang bridge in this city to stop the French troops advance in 1945-46.[19] The short biography in Vietnamese, together with an English translation, in this street-naming plan is provided in the document Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911-1966): A Biography.[4]

- ^ As recorded in the two books Đêm trắng của Đức Giáo Tông (Sleepless Night of the Cao Dai Pope)[20] and Dũng khí Nguyễn Ngọc Nhựt (The Heroic Nguyen Ngoc Nhut).[21] Chester L. Cooper in the book The lost Crusade: America in Vietnam wrote (pages 122-123) that he was ordered to go North.

- ^ Page 84 in Langguth (2002)[18]

- ^ Page 122-123 in Cooper (1970)[14].

- ^ In his speech at the twelfth anniversary of independence on September 2, 1957, Ho Chi Minh emphasized the consolidation and development of the economy in order to enhance the people's destiny. Regarding the South, he spoke of patience to reunify the country peacefully through general elections and advocated meetings and negotiations with the South, a position he reiterated on February 7, 1958 in New Delhi. On March 7, 1958, Pham Van Dong sent a letter to Ngo Dinh Diem, requesting meetings to reduce the army on each side and establish trade relations, the first steps towards future unification. The South Vietnamese government, learning from past communist actions against the nationalists (1945-46), did not believe in this outstretched hand. According to the documents (FRUS, 1961-1963, Volume IV, Vietnam, August-December 1963, D151) « In March 1962, Mr. Ho Chi Minh said, in an interview with journalist Wilfred Burchett, the his concern for a peaceful resolution of the Vietnam issue [... and] in September [of the same year], the Indian President of the ICC (International Control).[23]

- ^ "In March 1962, Ho Chi Minh said, in an interview with journalist Wilfred Burchett, his concern for a peaceful resolution of the Vietnam issue [... and] in September [of the same year], the Indian President of the ICC (International Control Commission) reported that Ho Chi Minh had said that he was prepared to extend a hand of friendship to Ngo Dinh Diem ('a patriotic'), and the North and the South can initiate some steps towards a modus vivendi, including the exchange of members of divided families."[23]

- ^ Nguyen Van Thoai comes from a famous Catholic family in the South. His brother, Nguyen Van At, married Ngo Dinh Thi Hiep, one of Ngo Dinh Diem's two sisters, and their son was later Cardinal Nguyen Van Thuan, the co-vice archbishop of Saigon. Nguyen Ngoc Bich is the son of one of the founders of Cao Dai (three million followers).

- ^ Nguyen-Ngoc-Nhut's name was given to a street in Ho Chi Minh City and in Ben Tre city.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Buttinger 1967b.

- ^ a b Nguyen-Ngoc-Bich 1962.

- ^ a b c d Nguyen-Ngoc-Chau 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Nguyen-Ngoc-Chau & Vu-Quoc-Loc 2023.

- ^ a b c d Honey, P.J. 1962.

- ^ a b Pace 2001.

- ^ a b c d e f Hammer 1954.

- ^ a b Gettleman 1967.

- ^ a b Osborne 1967.

- ^ a b Lancaster 1961.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tønnesson 2010.

- ^ a b Fox 2005.

- ^ a b Colman 2012.

- ^ a b c d Cooper 1970.

- ^ a b c Lambert 1992.

- ^ a b c Buttinger 1967a.

- ^ Scigliano 1978.

- ^ a b Langguth 2002.

- ^ a b CTDN 2019.

- ^ Tram-Huong 2003.

- ^ a b Nguyen-Hung 2003.

- ^ Nguyen-Ngoc-Chau 2023.

- ^ a b FRUS, 1963 & No.151.

- ^ Tong 2018.

References

[edit]- "151: Memorandum Prepared for the Director of Central Intelligence (McCone)", Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961-1963, Volume IV, Vietnam, August-December 1963, 1963, retrieved 15 Mar 2023. Internet archived 2022.11.15.

- "Street-naming plan in Can Tho, Vietnam, with biographies, Appendix 1", The Can Tho Daily News, 9 Apr 2019, archived from the original on 2023-02-10, retrieved 15 Mar 2023

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link). Internet archived 2023.02.10.

- Buttinger, Joseph (1967a), Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled, Vol.1, Frederik A. Praegers, New York, retrieved 25 Feb 2023

- Buttinger, Joseph (1967b), Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled, Vol.2, Frederik A. Praegers, New York, retrieved 25 Feb 2023

- Cooper, Chester L. (1970), The Lost Crusade: America in Vietnam, Dood, Mead & Company, New York, retrieved 7 Mar 2023

- Colman, Jonathan (2012), "Lost crusader? Chester L. Cooper and the Vietnam War, 1963–68", Cold War History, 12 (3): 429–449, doi:10.1080/14682745.2011.573147, S2CID 154769990.

- Fox, Margalit (2005), "Chester Cooper, 88, a Player in Diplomacy for Two Decades, Is Dead", The New York Times, Nov 7.

- Gettleman, Marvin E. (1967), A Vietnam Bibliography (PDF), Assistant Professor of History, Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, with the assistance of Sanford L. Silverman, Liberal Arts Bibliographer. The Libraries, Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, Oct 19. Internet archived 2022.01.01

- Hammer, Ellen J. (1954), The Struggle for Indochina, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, retrieved 11 Mar 2023.

- Honey, P.J., ed. (March 1962), "Special Issue on Vietnam", The China Quarterly, 9, retrieved 18 Feb 2023

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link). Volume 9 contained the articles written by several well-known intellectuals on Vietnam history and politics such as Bernard B. Fall, Hoang Van Chi, Phillipe Devillers (see French Cochinchina, Ref. 40), P. J. Honey, William Kaye (see e.g., A Bowl of Rice Divided: The Economy of North Vietnam, 1962), Gerard Tongas, among others. See the Editorial and the brief introduction of the contributors.

- Lambert, Bruce (1992), "Joseph A. Buttinger, Nazi Fighter And Vietnam Scholar, Dies at 85", The New York Times, Mar 8.

- Lancaster, Donald (1961), The Emancipation of French Indochina, Royal Institute of International Affairs, Oxford University Press, New York; reprinted by Octagon Books, New York, 1975, retrieved 11 Mar 2023

- Langguth, Arthur John (2002), Our Vietnam: The war, 1954-1975, Simon & Schuster, New York, retrieved 14 Mar 2023

- Nguyen-Hung (2003), Dũng khí Nguyễn Ngọc Nhựt (The Heroic Nguyen Ngoc Nhut), Nam Bộ Nhân Vật Chí (History of notable personalities in South Vietnam), Trẻ (Youth), Ho-Chi-Minh City, Vietnam.

- Nguyen-Ngoc-Bich (March 1962), "Vietnam—An Independent Viewpoint", The China Quarterly, 9, retrieved 18 Feb 2023

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link), pp. 105-111. See also the contents of Volume 9, which included the articles of many well-known experts on Vietnam history and politics.

- Nguyen-Ngoc-Chau (2018), Le Temps des Ancêtres: Une famille vietnamienne dans sa traversée du XXe siècle, L’Harmattan, Paris, France, retrieved 18 Feb 2023. Preface by historian Pierre Brocheux.

- Nguyen-Ngoc-Chau (2023), Viet Nam Political History of the Two Wars: Independence War (1858-1954) and Ideological War (1945-1975), Nombre 7, Nîmes, France.

- Nguyen-Ngoc-Chau; Vu-Quoc-Loc (2023), Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911-1966): A Biography, retrieved 21 Mar 2023, Internet Archive, CC-BY-SA 4.0. (Backup copy.) Much of the information in the present article came from this biography, which also contains many relevant and informative photos not displayed here. The version on the Internet Archive will be frequently updated. The older version on Commons remains fixed.

- Osborne, Milton (1967), "Viet-Nam: The Search for Absolutes", International Journal, Fifty Years of Bolshevism (Autumn, 1967), 22 (4): 647–654, doi:10.2307/40200203, JSTOR 40200203, retrieved 18 Feb 2023.

- Pace, Eric (2001), "Ellen Hammer, 79; Historian Wrote on French in Indochina", The New York Times, Mar 26.

- Scigliano, Robert (1978), South Vietnam: Nation under Stress, Praeger, New York.

- Tong, Traci (2018), "How the Vietnam War's Napalm Girl found hope after tragedy, The World from PRX", The World, Feb 21. Internet archived on 2023.02.22.

- Tønnesson, Stein (2010), Vietnam 1946: How the War Began, University of California Press, Berkeley, California.

- Tram-Huong (2003), Đêm trắng của Đức Giáo Tông (Sleepless Night of the Cao Dai Pope), People's Police Publishing House, Vietnam.

Gallery

[edit]Nguyen Ngoc Bich

[edit]Images used to illustrate this article.

-

Nguyen Ngoc Bich Street

-

Signature 1949

-

Nguyen Ngoc Bich 1931 Ecole polytechnique

-

Nguyen Ngoc Bich, circa 1933, Ecole polytechnique

-

Publisher Minh-Tan logo

-

Nguyen Ngoc Nhut (1918-1952)

-

Le Temps des Ancêtres: Une famille vietnamienne dans sa traversée du XXe siècle, book cover

-

Dr. Henriette Bui

First Indochina War

[edit]Images used to illustrate this article.

-

1945 Aug 16 Deer Team train Vietminh

-

OSS Deer team training the Viet Minh to use a grenade launcher.

-

1945 Aug OSS Maj. Allison Thomas and Viet-Minh fighters marching to Hanoi, Aug 1945.

-

OSS Maj. Archimedes Patti and Vo Nguyen Giap saluted American flag, with a Viet Minh band playing the Star Spangled Banner, 1945 Aug 26, Sunday.

-

Vo Nguyen Giap gave a welcoming parade to US Maj. Archimedes Patti, head of the US Army intelligence team (OSS), 1945 Aug 26, Sunday.

-

Vietnam Independence or Death demonstration, August 1945.

-

Ho Chi Minh declared Vietnam independence, 1945 Sep 2.

-

Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap giving a farewell party to the US Army intelligence team (OSS), 1945.

-

French plane pulling up after a dive to drop napalm bombs on Vietminh force ambushing a French battalion.

-

French napalm bomb exploded over Vietminh force. 1953 December.

-

French Marines wading ashore off the coast of Annam (Central Vietnam) in July 1950.

-

A Viet-Minh suspect captured by a French-Foreign-Legion patrol in 1954.

-

Vietnamese refugees boarding the US Navy ship LST 516 during Operation Passage to Freedom, October 1954.

-

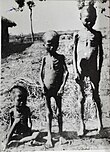

The great Vietnamese famine 1944–1945.

-

1945.09.02 Archimedes Patti Operational Priority communication

-

de Gaulle visited Truman, 1946 Aug 12

Second Indochina War

[edit]Images used to illustrate this article.

-

US Marines wading ashore in Da Nang, Central Vietnam, on 1965 Apr 30

Category:1911 births Category:1966 deaths Category:Vietnamese engineers Category:Vietnamese nationalists Category:Vietnamese physicians Category:Vietnamese politicians