User:Eetutus/sandbox

Kingdom of Spain | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Plus ultra" (Latin) "Further Beyond" | |

| Anthem: "Marcha Real" (Spanish)[2] "Royal March" | |

Location of Spain (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Madrid 40°26′N 3°42′W / 40.433°N 3.700°W |

| Official language and national language | Spanish[c] |

| Ethnic groups (2018)[4] |

|

| Religion (2019)[5] |

|

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Felipe VI |

| Pedro Sánchez | |

| Pío García-Escudero | |

| Ana Pastor Julián | |

| Carlos Lesmes Serrano | |

| Legislature | Cortes Generales |

| Senate | |

| Congress of Deputies | |

| Formation | |

| 20 January 1469 | |

• De facto | 23 January 1516 |

• De jure | 9 June 1715 |

| 19 March 1812 | |

| 29 December 1978 | |

| 1 January 1986 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 505,990[6] km2 (195,360 sq mi) (51st) |

• Water (%) | 1.04 |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | |

• Density | 92/km2 (238.3/sq mi) (112th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $1.864 trillion[8] (16th) |

• Per capita | $40,290[8] (31st) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $1.506 trillion[8] (12th) |

• Per capita | $32,559[8] (30th) |

| Gini (2017) | medium inequality (103rd) |

| HDI (2017) | very high (26th) |

| Currency | Euro[f] (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC±0 to +1 (WET and CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+1 to +2 (WEST and CEST) |

| Note: most of Spain observes CET/CEST, except the Canary Islands and Plazas de soberanía which observe WET/WEST | |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (CE) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +34 |

| ISO 3166 code | ES |

| Internet TLD | .es[g] |

Spain (Spanish: España [esˈpaɲa] ), officially the Kingdom of Spain[11] (Spanish: Reino de España),[a][b] is a country mostly located in Europe. Its continental European territory is situated on the Iberian Peninsula. Its territory also includes two archipelagoes: the Canary Islands off the coast of Africa, and the Balearic Islands in the Mediterranean Sea. The African enclaves of Ceuta, Melilla, and Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera[12] make Spain the only European country to have a physical border with an African country (Morocco).[h] Several small islands in the Alboran Sea are also part of Spanish territory. The country's mainland is bordered to the south and east by the Mediterranean Sea except for a small land boundary with Gibraltar; to the north and northeast by France, Andorra, and the Bay of Biscay; and to the west and northwest by Portugal and the Atlantic Ocean.

With an area of 505,990 km2 (195,360 sq mi), Spain is the largest country in Southern Europe, the second largest country in Western Europe and the European Union, and the fourth largest country in the European continent. By population, Spain is the sixth largest in Europe and the fifth in the European Union. Spain's capital and largest city is Madrid; other major urban areas include Barcelona, Valencia, Seville, Málaga and Bilbao.

Modern humans first arrived in the Iberian Peninsula around 35,000 years ago. Iberian cultures along with ancient Phoenician, Greek, Celtic and Carthaginian settlements developed on the peninsula until it came under Roman rule around 200 BCE, after which the region was named Hispania, based on the earlier Phoenician name Sp(a)n or Spania.[13] At the end of the Western Roman Empire the Germanic tribal confederations migrated from Central Europe, invaded the Iberian peninsula and established relatively independent realms in its western provinces, including the Suebi, Alans and Vandals. Eventually, the Visigoths would forcibly integrate all remaining independent territories in the peninsula, including Byzantine provinces, into the Kingdom of Toledo, which more or less unified politically, ecclesiastically and legally all the former Roman provinces or successor kingdoms of what was then documented as Hispania.

In the early eighth century the Visigothic Kingdom fell to the Moors of the Umayyad Islamic Caliphate, who arrived to rule most of the peninsula in the year 726, leaving only a handful of small Christian realms in the north and lasting up to seven centuries in the Kingdom of Granada. This led to many wars during a long reconquering period across the Iberian Peninsula, which led to the creation of Kingdom of Leon, Kingdom of Castille, Kingdom of Aragon and Kingdom of Navarre as the main Christian kingdoms to face the invasion. Following the Moorish conquest, Europeans began a gradual process of retaking the region known as the Reconquista,[14] which by the late 15th century culminated in the emergence of Spain as a unified country under the Catholic Monarchs.

In the early modern period, Spain became the world's first global empire and the most powerful country in the world, leaving a large cultural and linguistic legacy that includes +570 million Hispanophones,[15] making Spanish the world's second-most spoken native language, after Mandarin Chinese. During the Golden Age there were also many advancements in the arts, with world-famous painters such as Diego Velázquez. The most famous Spanish literary work, Don Quixote, was also published during the Golden Age. Spain hosts the world's third-largest number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Spain is a secular parliamentary democracy and a parliamentary monarchy,[16] with King Felipe VI as head of state. It is a major developed country[17] and a high income country, with the world's fourteenth largest economy by nominal GDP and sixteenth largest by purchasing power parity. It is a member of the United Nations (UN), the European Union (EU), the Eurozone, the Council of Europe (CoE), the Organization of Ibero-American States (OEI), the Union for the Mediterranean, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the Schengen Area, the World Trade Organization (WTO) and many other international organisations. While not an official member, Spain has a "Permanent Invitation" to the G20 summits, participating in every summit, which makes Spain a de facto member of the group.[18]

Etymology

[edit]The origins of the Roman name Hispania, from which the modern name España was derived, are uncertain due to inadequate evidence, although it is documented that the Phoenicians and Carthaginians referred to the region as Spania, therefore the most widely accepted etymology is a Semitic-Phoenician one.[13][19] Down the centuries there have been a number of accounts and hypotheses:

The Renaissance scholar Antonio de Nebrija proposed that the word Hispania evolved from the Iberian word Hispalis, meaning "city of the western world".

Jesús Luis Cunchillos argues that the root of the term span is the Phoenician word spy, meaning "to forge metals". Therefore, i-spn-ya would mean "the land where metals are forged".[20] It may be a derivation of the Phoenician I-Shpania, meaning "island of rabbits", "land of rabbits" or "edge", a reference to Spain's location at the end of the Mediterranean; Roman coins struck in the region from the reign of Hadrian show a female figure with a rabbit at her feet,[21] and Strabo called it the "land of the rabbits".[22] The word in question (compare modern Hebrew Shafan) actually means "Hyrax", possibly due to Phoenicians confusing the two animals.[23]

Hispania may derive from the poetic use of the term Hesperia, reflecting the Greek perception of Italy as a "western land" or "land of the setting sun" (Hesperia, Ἑσπερία in Greek) and Spain, being still further west, as Hesperia ultima.[24]

There is the claim that "Hispania" derives from the Basque word Ezpanna meaning "edge" or "border", another reference to the fact that the Iberian Peninsula constitutes the southwest corner of the European continent.[24]

Two 15th-century Spanish Jewish scholars, Don Isaac Abravanel and Solomon ibn Verga, gave an explanation now considered folkloric. Both men wrote in two different published works that the first Jews to reach Spain were brought by ship by Phiros who was confederate with the king of Babylon when he laid siege to Jerusalem. Phiros was a Grecian by birth, but who had been given a kingdom in Spain. Phiros became related by marriage to Espan, the nephew of king Heracles, who also ruled over a kingdom in Spain. Heracles later renounced his throne in preference for his native Greece, leaving his kingdom to his nephew, Espan, from whom the country of España (Spain) took its name. Based upon their testimonies, this eponym would have already been in use in Spain by c. 350 BCE.[25]

History

[edit]

Iberia enters written records as a land populated largely by the Iberians, Basques and Celts. Early on its coastal areas were settled by Phoenicians who founded Western Europe's most ancient cities Cadiz and Malaga. Phoenician influence expanded as much of the Peninsula was eventually incorporated into the Carthaginian Empire, becoming a major theatre of the Punic Wars against the expanding Roman Empire. After an arduous conquest, the peninsula came fully under Roman Rule. During the early Middle Ages it came under Gothic rule but later, much of it was conquered by Muslim invaders from North Africa. In a process that took centuries, the small Christian kingdoms in the north gradually regained control of the peninsula. The last Muslim state fell in the same year Columbus reached the Americas. A global empire began which saw Spain become the strongest kingdom in Europe, the leading world power for a century and a half, and the largest overseas empire for three centuries.

Continued wars and other problems eventually led to a diminished status. The Napoleonic invasions of Spain led to chaos, triggering independence movements that tore apart most of the empire and left the country politically unstable. Prior to the Second World War, Spain suffered a devastating civil war and came under the rule of an authoritarian government, which oversaw a period of stagnation that was followed by a surge in the growth of the economy. Eventually democracy was peacefully restored in the form of a parliamentary constitutional monarchy. Spain joined the European Union, experiencing a cultural renaissance and steady economic growth until the beginning of the 21st century, that started a new globalised world with economic and ecological challenges.

Prehistory and pre-Roman peoples

[edit]Archaeological research at Atapuerca indicates the Iberian Peninsula was populated by hominids 1.2 million years ago.[27] In Atapuerca fossils have been found of the earliest known hominins in Europe, the Homo antecessor. Modern humans first arrived in Iberia, from the north on foot, about 35,000 years ago.[28][failed verification] The best known artefacts of these prehistoric human settlements are the famous paintings in the Altamira cave of Cantabria in northern Iberia, which were created from 35,600 to 13,500 BCE by Cro-Magnon.[26][29] Archaeological and genetic evidence suggests that the Iberian Peninsula acted as one of several major refugia from which northern Europe was repopulated following the end of the last ice age.

The largest groups inhabiting the Iberian Peninsula before the Roman conquest were the Iberians and the Celts. The Iberians inhabited the Mediterranean side of the peninsula, from the northeast to the southeast. The Celts inhabited much of the inner and Atlantic sides of the peninsula, from the northwest to the southwest. Basques occupied the western area of the Pyrenees mountain range and adjacent areas, the Phoenician-influenced Tartessians culture flourished in the southwest and the Lusitanians and Vettones occupied areas in the central west. A number of cities were founded along the coast by Phoenicians, and trading outposts and colonies were established by Greeks in the East. Eventually, Phoenician-Carthaginians expanded inland towards the meseta, however due to the bellicose inland tribes the Carthaginians got settled in the coasts of the Iberian Peninsula.

Roman Hispania and the Visigothic Kingdom

[edit]

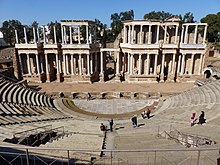

During the Second Punic War, roughly between 210 and 205 BC the expanding Roman Republic captured Carthaginian trading colonies along the Mediterranean coast. Although it took the Romans nearly two centuries to complete the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, they retained control of it for over six centuries. Roman rule was bound together by law, language, and the Roman road.[30]

The cultures of the Celtic and Iberian populations were gradually Romanised (Latinised) at different rates depending on what part of Hispania they lived in, with local leaders being admitted into the Roman aristocratic class.[i][31] Hispania served as a granary for the Roman market, and its harbours exported gold, wool, olive oil, and wine. Agricultural production increased with the introduction of irrigation projects, some of which remain in use. Emperors Hadrian, Trajan, Theodosius I, and the philosopher Seneca were born in Hispania.[j] Christianity was introduced into Hispania in the 1st century AD and it became popular in the cities in the 2nd century AD.[31] Most of Spain's present languages and religion, and the basis of its laws, originate from this period.[30]

The weakening of the Western Roman Empire's jurisdiction in Hispania began in 409, when the Germanic Suebi and Vandals, together with the Sarmatian Alans entered the peninsula at the invitation of a Roman usurper. These tribes had crossed the Rhine in early 407 and ravaged Gaul. The Suebi established a kingdom in what is today modern Galicia and northern Portugal whereas the Vandals established themselves in southern Spain by 420 before crossing over to North Africa in 429 and taking Carthage in 439. As the western empire disintegrated, the social and economic base became greatly simplified: but even in modified form, the successor regimes maintained many of the institutions and laws of the late empire, including Christianity and assimilation to the evolving Roman culture.

The Byzantines established an occidental province, Spania, in the south, with the intention of reviving Roman rule throughout Iberia. Eventually, however, Hispania was reunited under Visigothic rule. These Visigoths, or Western Goths, after sacking Rome under the leadership of Alaric (410), turned towards the Iberian Peninsula, with Athaulf for their leader, and occupied the northeastern portion. Wallia extended his rule over most of the peninsula, keeping the Suebians shut up in Galicia. Theodoric I took part, with the Romans and Franks, in the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, where Attila was routed. Euric (466), who put an end to the last remnants of Roman power in the peninsula, may be considered the first monarch of Spain, though the Suebians still maintained their independence in Galicia. Euric was also the first king to give written laws to the Visigoths. In the following reigns the Catholic kings of France assumed the role of protectors of the Hispano-Roman Catholics against the Arianism of the Visigoths, and in the wars which ensued Alaric II and Amalaric lost their lives.

Athanagild, having risen against King Agila, called in the Byzantines and, in payment for the succour they gave him, ceded to them the maritime places of the southeast (554). Liuvigild restored the political unity of the peninsula, subduing the Suebians, but the religious divisions of the country, reaching even the royal family, brought on a civil war. St. Hermengild, the king's son, putting himself at the head of the Catholics, was defeated and taken prisoner, and suffered martyrdom for rejecting communion with the Arians. Recared, son of Liuvigild and brother of St. Hermengild, added religious unity to the political unity achieved by his father, accepting the Catholic faith in the Third Council of Toledo (589). The religious unity established by this council was the basis of that fusion of Goths with Hispano-Romans which produced the Spanish nation. Sisebut and Suintila completed the expulsion of the Byzantines from Spain.[32]

Intermarriage between Visigoths and Hispano-Romans was prohibited, though in practice it could not be entirely prevented and was eventually legalised by Liuvigild.[33] The Spanish-Gothic scholars such as Braulio of Zaragoza and Isidore of Seville played an important role in keeping the classical Greek and Roman culture. Isidore was one of the most influential clerics and philosophers in the Middle Ages in Europe, and his theories were also vital to the conversion of the Visigothic Kingdom from an Arian domain to a Catholic one in the Councils of Toledo. Isidore created the first western encyclopaedia which had a huge impact during the Middle Ages.[34]

Muslim era and Reconquista

[edit]

In the 8th century, nearly all of the Iberian Peninsula was conquered (711–718) by largely Moorish Muslim armies from North Africa. These conquests were part of the expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate. Only a small area in the mountainous north-west of the peninsula managed to resist the initial invasion. Legend has it that Count Julian, the governor of Ceuta, in revenge for the violation of his daughter, Florinda, by King Roderic, invited the Muslims and opened to them the gates of the peninsula.

Under Islamic law, Christians and Jews were given the subordinate status of dhimmi. This status permitted Christians and Jews to practice their religions as People of the Book but they were required to pay a special tax and had legal and social rights inferior to those of Muslims.[35][36]

Conversion to Islam proceeded at an increasing pace. The muladíes (Muslims of ethnic Iberian origin) are believed to have formed the majority of the population of Al-Andalus by the end of the 10th century.[37][38]

The Muslim community in the Iberian Peninsula was itself diverse and beset by social tensions. The Berber people of North Africa, who had provided the bulk of the invading armies, clashed with the Arab leadership from the Middle East.[k] Over time, large Moorish populations became established, especially in the Guadalquivir River valley, the coastal plain of Valencia, the Ebro River valley and (towards the end of this period) in the mountainous region of Granada.[38]

Córdoba, the capital of the caliphate since Abd-ar-Rahman III, was the largest, richest and most sophisticated city in western Europe. Mediterranean trade and cultural exchange flourished. Muslims imported a rich intellectual tradition from the Middle East and North Africa. Some important philosophers at the time were Averroes, Ibn Arabi and Maimonides. The Romanised cultures of the Iberian Peninsula interacted with Muslim and Jewish cultures in complex ways, giving the region a distinctive culture.[38] Outside the cities, where the vast majority lived, the land ownership system from Roman times remained largely intact as Muslim leaders rarely dispossessed landowners and the introduction of new crops and techniques led to an expansion of agriculture introducing new produces which originally came from Asia or the former territories of the Roman Empire.[39]

In the 11th century, the Muslim holdings fractured into rival Taifa states (Arab, Berber, and Slav),[40] allowing the small Christian states the opportunity to greatly enlarge their territories.[38] The arrival from North Africa of the Islamic ruling sects of the Almoravids and the Almohads restored unity upon the Muslim holdings, with a stricter, less tolerant application of Islam, and saw a revival in Muslim fortunes. This re-united Islamic state experienced more than a century of successes that partially reversed Christian gains.

The Reconquista (Reconquest) was the centuries-long period in which Christian rule was re-established over the Iberian Peninsula. The Reconquista is viewed as beginning with the Battle of Covadonga won by Don Pelayo in 722 and was concurrent with the period of Muslim rule on the Iberian Peninsula. The Christian army's victory over Muslim forces led to the creation of the Christian Kingdom of Asturias along the northwestern coastal mountains. Shortly after, in 739, Muslim forces were driven from Galicia, which was to eventually host one of medieval Europe's holiest sites, Santiago de Compostela and was incorporated into the new Christian kingdom. The Kingdom of León was the strongest Christian kingdom for centuries. In 1188 the first modern parliamentary session in Europe was held in León (Cortes of León). The Kingdom of Castile, formed from Leonese territory, was its successor as strongest kingdom. The kings and the nobility fought for power and influence in this period. The example of the Roman emperors influenced the political objective of the Crown, while the nobles benefited from feudalism.

Muslim armies had also moved north of the Pyrenees but they were defeated by Frankish forces at the Battle of Poitiers, Frankia and pushed out of the very southernmost region of France along the seacoast by the 760s. Later, Frankish forces established Christian counties on the southern side of the Pyrenees. These areas were to grow into the kingdoms of Navarre and Aragon.[41] For several centuries, the fluctuating frontier between the Muslim and Christian controlled areas of Iberia was along the Ebro and Douro valleys.

The County of Barcelona and the Kingdom of Aragon entered in a dynastic union and gained territory and power in the Mediterranean. In 1229 Majorca was conquered, so was Valencia in 1238. The break-up of Al-Andalus into the competing taifa kingdoms helped the long embattled Iberian Christian kingdoms gain the initiative. The capture of the strategically central city of Toledo in 1085 marked a significant shift in the balance of power in favour of the Christian kingdoms. Following a great Muslim resurgence in the 12th century, the great Moorish strongholds in the south fell to Christian Spain in the 13th century—Córdoba in 1236 and Seville in 1248. In the 13th and 14th centuries, the Marinid dynasty of Morocco invaded and established some enclaves on the southern coast but failed in their attempt to re-establish North African rule in Iberia and were soon driven out. After 800 years of Muslim presence in Spain, the last Nasrid sultanate of Granada, a tributary state would finally surrender in 1492 to the Catholic monarchs Queen Isabella I of Castile[42] and King Ferdinand II of Aragon.[43][44][45]

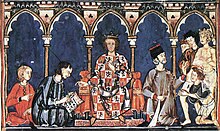

From the mid 13th century, literature and philosophy started to flourish again in the Christian peninsular kingdoms, based on Roman and Gothic traditions. An important philosopher from this time is Ramon Llull. Abraham Cresques was a prominent Jewish cartographer. Roman law and its institutions were the model for the legislators. The king Alfonso X of Castile focused on strengthening this Roman and Gothic past, and also on linking the Iberian Christian kingdoms with the rest of medieval European Christendom. Alfonso worked for being elected emperor of the Holy Roman Empire and published the Siete Partidas code. The Toledo School of Translators is the name that commonly describes the group of scholars who worked together in the city of Toledo during the 12th and 13th centuries, to translate many of the philosophical and scientific works from Classical Arabic, Ancient Greek, and Ancient Hebrew.

The Islamic transmission of the classics is the main Islamic contributions to Medieval Europe. The Castilian language—more commonly known (especially later in history and at present) as "Spanish" after becoming the national language and lingua franca of Spain—evolved from Vulgar Latin, as did other Romance languages of Spain like the Catalan, Asturian and Galician languages, as well as other Romance languages in Latin Europe. Basque, the only non-Romance language in Spain, continued evolving from Early Basque to Medieval. The Glosas Emilianenses founded in the monasteries of San Millán de la Cogolla contain the first written words in both Basque and Spanish, having the first become an influence in the formation of the second as an evolution of Latin.

The 13th century also witnessed the Crown of Aragon, centred in Spain's north east, expand its reach across islands in the Mediterranean, to Sicily and Naples.[46] Around this time the universities of Palencia (1212/1263) and Salamanca (1218/1254) were established. The Black Death of 1348 and 1349 devastated Spain.[47]

The Catalans and Aragonese offered themselves to the Byzantine Emperor Andronicus II Palaeologus to fight the Turks. Having conquered these, they turned their arms against the Byzantines, who treacherously slew their leaders; but for this treachery the Spaniards, under Bernard of Rocafort and Berenguer of Entenca, exacted the terrible penalty celebrated in history as "The Catalan Vengeance" and moreover seized the Frankish Duchy of Athens (1311).[32] The royal line of Aragon became extinct with Martin the Humane, and the Compromise of Caspe gave the Crown to the dynasty of Castile, thus preparing the final union.

Anti-Semitic animus accompanied the Reconquista. There were mass killings in Aragon in the mid-14th century, and 12,000 Jews were killed in Toledo. In 1391, Christian mobs went from town to town throughout Castile and Aragon, killing an estimated 50,000 Jews.[48][49][50][51][52][53] Women and children were sold as slaves to Muslims, and many synagogues were converted into churches. According to Hasdai Crescas, about 70 Jewish communities were destroyed.[54] St. Vincent Ferrer converted innumerable Jews, among them the Rabbi Josuah Halorqui, who took the name of Jerónimo de Santa Fe and in his town converted many of his former coreligionists in the famous Disputation of Tortosa (1413–14).

Spanish Empire

[edit]

In 1469, the crowns of the Christian kingdoms of Castile and Aragon were united by the marriage of Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon. 1478 commenced the completion of the conquest of the Canary Islands and in 1492, the combined forces of Castile and Aragon captured the Emirate of Granada from its last ruler Muhammad XII, ending the last remnant of a 781-year presence of Islamic rule in Iberia. That same year, Spain's Jews were ordered to convert to Catholicism or face expulsion from Spanish territories during the Spanish Inquisition.[55] As many as 200,000 Jews were expelled from Spain.[56][57][58] This was followed by expulsions in 1493 in Aragonese Sicily and Portugal in 1497. The Treaty of Granada guaranteed religious tolerance towards Muslims,[59] for a few years before Islam was outlawed in 1502 in the Kingdom of Castile and 1527 in the Kingdom of Aragon, leading to Spain's Muslim population becoming nominally Christian Moriscos. A few decades after the Morisco rebellion of Granada known as the War of the Alpujarras, a significant proportion of Spain's formerly-Muslim population was expelled, settling primarily in North Africa.[l][60] From 1609–14, over 300,000 Moriscos were sent on ships to North Africa and other locations, and, of this figure, around 50,000 died resisting the expulsion, and 60,000 died on the journey.[61][62][63]

The year 1492 also marked the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the New World, during a voyage funded by Isabella. Columbus's first voyage crossed the Atlantic and reached the Caribbean Islands, beginning the European exploration and conquest of the Americas, although Columbus remained convinced that he had reached the Orient. Large numbers of indigenous Americans died in battle against the Spaniards during the conquest,[64] while others died from various other causes. Some scholars consider the initial period of the Spanish conquest— from Columbus's first landing in the Bahamas until the middle of the sixteenth century—as marking the most egregious case of genocide in the history of mankind.[65] The death toll may have reached some 70 million indigenous people (out of 80 million) in this period.[65]

The colonisation of the Americas started with conquistadores like Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro. Miscegenation was the rule between the native and the Spanish cultures and people. Juan Sebastian Elcano completed the first voyage around the world in human history, the Magellan-Elcano circumnavigation. Florida was colonised by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés when he founded St. Augustine, Florida and then defeated an attempt led by the French Captain Jean Ribault to establish a French foothold in Spanish Florida territory. St. Augustine became a strategic defensive base for Spanish ships full of gold and silver sailing to Spain. Andrés de Urdaneta discovered the tornaviaje or return route from the Philippines to Mexico, making possible the Manila galleon trading route. The Spanish once again encountered Islam, but this time in Southeast Asia and in order to incorporate the Philippines, Spanish expeditions organised from newly Christianised Mexico had invaded the Philippine territories of the Sultanate of Brunei. The Spanish considered the war with the Muslims of Brunei and the Philippines, a repeat of the Reconquista.[66] The Spanish explorer Blas Ruiz intervened in Cambodia's succession and installed Crown Prince Barom Reachea II as puppet.[67]

As Renaissance New Monarchs, Isabella and Ferdinand centralised royal power at the expense of local nobility, and the word España, whose root is the ancient name Hispania, began to be commonly used to designate the whole of the two kingdoms.[60] With their wide-ranging political, legal, religious and military reforms, Spain emerged as the first world power. The death of their son Prince John caused the Crown to pass to Charles I (the Emperor Charles V), son of Juana la Loca.

The unification of the crowns of Aragon and Castile by the marriage of their sovereigns laid the basis for modern Spain and the Spanish Empire, although each kingdom of Spain remained a separate country socially, politically, legally, and in currency and language.[68][69]

There were two big revolts against the new Habsburg monarch and the more authoritarian and imperial-style crown: Revolt of the Comuneros in Castile and Revolt of the Brotherhoods in Majorca and Valencia. After years of combat, Comuneros Juan López de Padilla, Juan Bravo and Francisco Maldonado were executed and María Pacheco went into exile. Germana de Foix also finished with the revolt in the Mediterranean.

Habsburg Spain was Europe's leading power throughout the 16th century and most of the 17th century, a position reinforced by trade and wealth from colonial possessions and became the world's leading maritime power. It reached its apogee during the reigns of the first two Spanish Habsburgs—Charles I (1516–1556) and Philip II (1556–1598). This period saw the Italian Wars, the Schmalkaldic War, the Dutch Revolt, the War of the Portuguese Succession, clashes with the Ottomans, intervention in the French Wars of Religion and the Anglo-Spanish War.[70]

Through exploration and conquest or royal marriage alliances and inheritance, the Spanish Empire expanded to include vast areas in the Americas, islands in the Asia-Pacific area, areas of Italy, cities in Northern Africa, as well as parts of what are now France, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. The first circumnavigation of the world was carried out in 1519–1521. It was the first empire on which it was said that the sun never set. This was an Age of Discovery, with daring explorations by sea and by land, the opening-up of new trade routes across oceans, conquests and the beginnings of European colonialism. Spanish explorers brought back precious metals, spices, luxuries, and previously unknown plants, and played a leading part in transforming the European understanding of the globe.[71] The cultural efflorescence witnessed during this period is now referred to as the Spanish Golden Age. The expansion of the empire caused immense upheaval in the Americas as the collapse of societies and empires and new diseases from Europe devastated American indigenous populations. The rise of humanism, the Counter-Reformation and new geographical discoveries and conquests raised issues that were addressed by the intellectual movement now known as the School of Salamanca, which developed the first modern theories of what are now known as international law and human rights. Juan Luis Vives was another prominent humanist during this period.

Spain's 16th century maritime supremacy was demonstrated by the victory over the Ottomans at Lepanto in 1571, and then after the setback of the Spanish Armada in 1588, in a series of victories against England in the Anglo-Spanish War of 1585–1604. However, during the middle decades of the 17th century Spain's maritime power went into a long decline with mounting defeats against the United Provinces and then England; that by the 1660s it was struggling grimly to defend its overseas possessions from pirates and privateers.

The Protestant Reformation dragged the kingdom ever more deeply into the mire of religiously charged wars. The result was a country forced into ever expanding military efforts across Europe and in the Mediterranean.[72] By the middle decades of a war- and plague-ridden 17th-century Europe, the Spanish Habsburgs had enmeshed the country in continent-wide religious-political conflicts. These conflicts drained it of resources and undermined the economy generally. Spain managed to hold on to most of the scattered Habsburg empire, and help the imperial forces of the Holy Roman Empire reverse a large part of the advances made by Protestant forces, but it was finally forced to recognise the separation of Portugal and the United Provinces, and eventually suffered some serious military reverses to France in the latter stages of the immensely destructive, Europe-wide Thirty Years' War.[73] In the latter half of the 17th century, Spain went into a gradual decline, during which it surrendered several small territories to France and England; however, it maintained and enlarged its vast overseas empire, which remained intact until the beginning of the 19th century.

The decline culminated in a controversy over succession to the throne which consumed the first years of the 18th century. The War of the Spanish Succession was a wide-ranging international conflict combined with a civil war, and was to cost the kingdom its European possessions and its position as one of the leading powers on the Continent.[74] During this war, a new dynasty originating in France, the Bourbons, was installed. Long united only by the Crown, a true Spanish state was established when the first Bourbon king, Philip V, united the crowns of Castile and Aragon into a single state, abolishing many of the old regional privileges and laws.[75]

The 18th century saw a gradual recovery and an increase in prosperity through much of the empire. The new Bourbon monarchy drew on the French system of modernising the administration and the economy. Enlightenment ideas began to gain ground among some of the kingdom's elite and monarchy. Bourbon reformers created formal disciplined militias across the Atlantic. Spain needed every hand it could take during the seemingly endless wars of the eighteenth century—the Spanish War of Succession or Queen Anne's War (1702–13), the War of Jenkins' Ear (1739–42) which became the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48), the Seven Years' War (1756–63) and the Anglo-Spanish War (1779–83)—and its new disciplined militias served around the Atlantic as needed.

Liberalism, labour movement and nation state

[edit]

In 1793, Spain went to war against the revolutionary new French Republic as a member of the first Coalition. The subsequent War of the Pyrenees polarised the country in a reaction against the gallicised elites and following defeat in the field, peace was made with France in 1795 at the Peace of Basel in which Spain lost control over two-thirds of the island of Hispaniola. The Prime Minister, Manuel Godoy, then ensured that Spain allied herself with France in the brief War of the Third Coalition which ended with the British naval victory at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. In 1807, a secret treaty between Napoleon and the unpopular prime minister led to a new declaration of war against Britain and Portugal. Napoleon's troops entered the country to invade Portugal but instead occupied Spain's major fortresses. The Spanish king abdicated in favour of Napoleon's brother, Joseph Bonaparte.

Joseph Bonaparte was seen as a puppet monarch and was regarded with scorn by the Spanish. The 2 May 1808 revolt was one of many nationalist uprisings across the country against the Bonapartist regime.[76] These revolts marked the beginning of a devastating war of independence against the Napoleonic regime.[77] The most celebrated battles of this war were those of Bruch, in the highlands of Montserrat, in which the Catalan peasantry routed a French army; Bailén, where Castaños, at the head of the army of Andalusia, defeated Dupont; and the sieges of Zaragoza and Girona, which were worthy of the ancient Spaniards of Saguntum and Numantia.[32]

Napoleon was forced to intervene personally, defeating several Spanish armies and forcing a British army to retreat. However, further military action by Spanish armies, guerrillas and Wellington's British-Portuguese forces, combined with Napoleon's disastrous invasion of Russia, led to the ousting of the French imperial armies from Spain in 1814, and the return of King Ferdinand VII.[78]

During the war, in 1810, a revolutionary body, the Cortes of Cádiz, was assembled to co-ordinate the effort against the Bonapartist regime and to prepare a constitution.[79] It met as one body, and its members represented the entire Spanish empire.[80] In 1812, a constitution for universal representation under a constitutional monarchy was declared, but after the fall of the Bonapartist regime, Ferdinand VII dismissed the Cortes Generales and was determined to rule as an absolute monarch. These events foreshadowed the conflict between conservatives and liberals in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Spain's conquest by France benefited Latin American anti-colonialists who resented the Imperial Spanish government's policies that favoured Spanish-born citizens (Peninsulars) over those born overseas (Criollos) and demanded retroversion of the sovereignty to the people. Starting in 1809 Spain's American colonies began a series of revolutions and declared independence, leading to the Spanish American wars of independence that ended Spanish control over its mainland colonies in the Americas. King Ferdinand VII's attempt to re-assert control proved futile as he faced opposition not only in the colonies but also in Spain and army revolts followed, led by liberal officers. By the end of 1826, the only American colonies Spain held were Cuba and Puerto Rico.

- ^ "Acuerdo entre el Reino de España y Nueva Zelanda sobre participación en determinadas elecciones de los nacionales de cada país residentes en el territorio del otro, hecho en Wellington el 23 de junio de 2009". Noticias Jurídicas.

- ^ Presidency of the Government (11 October 1997). "Real Decreto 1560/1997, de 10 de octubre, por el que se regula el Himno Nacional" (PDF). Boletín Oficial del Estado núm. 244 (in Spanish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ "The Spanish Constitution". Lamoncloa.gob.es. Archived from the original on 25 March 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ https://datosmacro.expansion.com/paises/espana

- ^ http://datos.cis.es/pdf/Es3238mar_A.pdf

- ^ "Anuario estadístico de España 2008. 1ª parte: entorno físico y medio ambiente" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadística (Spain). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ "Population Figures at 01 July 2018. Migrations Statistics. First half of 2018" (PDF) (in Spanish). National Statistics Institute (INE). 13 December 2018. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org.

- ^ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ "2016 Human Development Report" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ^ https://www.britannica.com/place/Spain

- ^ News, Morocco World (29 August 2012). "Spanish Military Arrest Four Moroccans after they Tried to Hoist Moroccan Flag in Badis Island". Morocco World News. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b "Iberia vs Hispania: Origen etimológico". Archived from the original on 27 December 2016.

- ^ Esparza, José Javier (2007). La gesta española : historia de España en 48 estampas, para quienes han olvidado cuál era su nación (1a. ed.). Barcelona: Áltera. ISBN 978-84-96840-14-0.

- ^ https://www.cervantes.es/sobre_instituto_cervantes/prensa/2017/noticias/Presentación-Anuario-2017.htm

- ^ "La Constitución española de 1978. Título preliminar" (in Spanish). Página oficial del Congreso de los Diputados. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ Whitehouse, Mark (6 November 2010). "Number of the Week: $10.2 Trillion in Global Borrowing". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017.

- ^ Henley, Peter H.; Blokker, Niels M. "The Group of 20: A Short Legal Anatomy" (PDF). Melbourne Journal of International Law. 14: 568. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

Spain's peculiar but seemingly secure position within the G20 also appears to have facilitated their greater participation in the G20's work: Spain is the only outreach participant to have made policy commitments comparable to those of G20 members proper at summits since Seoul. Spain therefore appears to have become a de facto member of the G20.

- ^ ABC. ""I-span-ya", el misterioso origen de la palabra España". Archived from the original on 13 November 2016.

- ^ #Linch, John (director), Fernández Castro, María Cruz (del segundo tomo), Historia de España, El País, volumen II, La península Ibérica en época prerromana, p. 40. Dossier. La etimología de España; ¿tierra de conejos?, ISBN 978-84-9815-764-2

- ^ Burke, Ulick Ralph (1895). A History of Spain from the Earliest Times to the Death of Ferdinand the Catholic, Volume 1. London: Longmans, Green & Co. p. 12. hdl:2027/hvd.fl29jg.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "Rabbits, fish and mice, but no rock hyrax". Understanding Animal Research.

- ^ a b Anthon, Charles (1850). A system of ancient and mediæval geography for the use of schools and colleges. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 14.

- ^ Abrabanel, Commentary on the First Prophets (Pirush Al Nevi'im Rishonim), end of II Kings, pp. 680–681, Jerusalem 1955 (Hebrew). See also Shelomo (also spelled Sholomo, Solomon or Salomón) ibn Verga, Shevet Yehudah, pp. 6b–7a, Lemberg 1846 (Hebrew)

- ^ a b (Pike et al. 2012, pp. 1409–14013)

- ^ "'First west Europe tooth' found". BBC. 30 June 2007. Archived from the original on 1 November 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- ^ Typical Aurignacian items were found in Cantabria (Morín, El Pendo, El Castillo), the Basque Country (Santimamiñe) and Catalonia. The radiocarbon datations give the following dates: 32,425 and 29,515 BP. [failed verification][

- ^ Bernaldo de Quirós Guidolti, Federico; Cabrera Valdés, Victoria (1994). "Cronología del arte paleolítico" (PDF). Complutum. 5: 265–276. ISSN 1131-6993. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ a b Payne, Stanley G. (1973). "A History of Spain and Portugal; Ch. 1 Ancient Hispania". The Library of Iberian Resources Online. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- ^ a b Rinehart, Robert; Seeley, Jo Ann Browning (1998). "A Country Study: Spain. Chapter 1 – Hispania". Library of Congress Country Series. Archived from the original on 22 September 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- ^ a b c Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire: Volume 1, Portugal: From Beginnings to 1807. Cambridge University Press. 2009. ISBN 978-1-107-71764-0.

- ^ Marcolongo, Andrea (2017). La lengua de los dioses: Nueve razones para amar el griego (in Greek). Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial España. ISBN 978-84-306-1887-3.

- ^ H. Patrick Glenn (2007). Legal Traditions of the World. Oxford University Press. pp. 218–219.

Dhimma provides rights of residence in return for taxes.

- ^ Lewis, Bernard (1984). The Jews of Islam. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-691-00807-3.

Dhimmi have fewer legal and social rights than Muslims, but more rights than other non-Muslims.

- ^ Islamic and Christian Spain in the Early Middle Ages. Chapter 5: Ethnic Relations, Thomas F. Glick

- ^ a b c d Payne, Stanley G. (1973). "A History of Spain and Portugal; Ch. 2 Al-Andalus". The Library of Iberian Resources Online. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- ^ Moa, Pío (2010). Nueva historia de España : de la II Guerra Púnica al siglo XXI (1. ed.). Madrid: Esfera de los Libros. ISBN 978-84-9734-952-9.

- ^ Classen, Albrecht (31 August 2015). Handbook of Medieval Culture, Volume 1. ISBN 9783110267303.

- ^ Rinehart, Robert; Seeley, Jo Ann Browning (1998). "A Country Study: Spain – Castile and Aragon". Library of Congress Country Series. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Isabella I". Newadvent.org. 1 October 1910. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "BBC – Religions – Islam: Muslim Spain (711–1492)". Archived from the original on 27 February 2017.

- ^ "Islamic History". Archived from the original on 12 March 2016.

- ^ "Europe & the Islamic Mediterranean AD 700–1600". Archived from the original on 6 March 2016.

- ^ Payne, Stanley G. (1973). "A History of Spain and Portugal; Ch. 5 The Rise of Aragon-Catalonia". The Library of Iberian Resources Online. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- ^ "The Black Death". Channel 4. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ Berger, Julia Phillips; Gerson, Sue Parker (2006). Teaching Jewish History. ISBN 9780867051834.

- ^ Kantor, Máttis (2005). Codex Judaica: Chronological Index of Jewish History, Covering 5,764 Years of Biblical, Talmudic & Post-Talmudic History. ISBN 9780967037837.

- ^ Aiken, Lisa (February 1997). Why Me God: A Jewish Guide for Coping and Suffering. ISBN 9781461695479.

- ^ Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R.; Skoggard, Ian (30 November 2004). Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Volume I: Overviews and Topics; Volume II: Diaspora Communities. ISBN 9780306483219.

- ^ Philip, Schaff (24 March 2015). The Christian Church from the 1st to the 20th Century.

- ^ Gilbert, Martin (2003). The Routledge Atlas of Jewish History. ISBN 9780415281508.

- ^ Anti-Jewish Riots in the Crown of Aragon and the Royal Response, 1391–1392. Cambridge University Press. 2016. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-107-16451-2.

- ^ "Spanish Inquisition left genetic legacy in Iberia". New Scientist. 4 December 2008. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ The Kingfisher History Encyclopedia. 9 September 2004. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-7534-5784-9.

- ^ Beck, Bernard (2012). True Jew: Challenging the Stereotype. ISBN 9780875869032.

- ^ Strom, Yale (1992). The Expulsion of the Jews: Five Hundred Years of Exodus. ISBN 9781561710812.

- ^ "The Treaty of Granada, 1492". Islamic Civilisation. Archived from the original on 24 September 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ a b Rinehart, Robert; Seeley, Jo Ann Browning (1998). "A Country Study: Spain – The Golden Age". Library of Congress Country Series. Archived from the original on 9 August 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- ^ Spanish Royal Patronage 1412–1804: Portraits as Propaganda. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. 2018. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-5275-1229-0.

- ^ Jaleel, Talib (11 July 2015). Notes On Entering Deen Completely: Islam as its followers know it.

- ^ Majid, Anouar (2009). We are All Moors: Ending Centuries of Crusades Against Muslims and Other Minorities. ISBN 9780816660797.

- ^ The Spanish Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. 2016. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-61069-422-3.

- ^ a b Naimark, Norman (2016). Genocide: A World History. p. 35.

- ^ Reviving the Reconquista in Southeast Asia: Moros and the Making of the Philippines, 1565–1662 By: Ethan P. Hawkley

- ^ Daniel George Edward Hall (1981). History of South-East Asia. Macmillan Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-333-24163-9.

- ^ "Imperial Spain". University of Calgary. Archived from the original on 29 June 2008. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ Handbook of European History. Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial España. 1994. ISBN 90-04-09760-0.

- ^ Payne, Stanley G. (1973). "A History of Spain and Portugal; Ch. 13 The Spanish Empire". The Library of Iberian Resources Online. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- ^ Thomas, Hugh (2003). Rivers of gold: the rise of the Spanish Empire. London: George Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. passim. ISBN 978-0-297-64563-4.

- ^ "The Seventeenth-Century Decline". The Library of Iberian resources online. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ Payne, Stanley G. (1973). "A History of Spain and Portugal; Ch. 14 Spanish Society and Economics in the Imperial Age". The Library of Iberian Resources Online. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- ^ Rinehart, Robert; Seeley, Jo Ann Browning (1998). "A Country Study: Spain – Spain in Decline". Library of Congress Country Series. Archived from the original on 9 August 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- ^ Rinehart, Robert; Seeley, Jo Ann Browning (1998). "A Country Study: Spain – Bourbon Spain". Library of Congress Country Series. Archived from the original on 9 August 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- ^ David A. Bell. "Napoleon's Total War". TheHistoryNet.com

- ^ (Gates 2001, p.20)

- ^ (Gates 2001, p.467)

- ^ Jaime Alvar Ezquerra (2001). Diccionario de historia de España. Ediciones Akal. p. 209. ISBN 978-84-7090-366-3. Cortes of Cádiz (1812) was the first parliament of Spain with sovereign power

- ^ Rodríguez. Independence of Spanish America. Cambridge University Press. [1] citation: "It met as one body, and its members represented the entire Spanish world"

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).