User:Dgmm116/Low-carbon diet

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

Article Draft

[edit]Lead

[edit]Article body

[edit]Background on diet and greenhouse gas emissions

[edit]In the U.S., the food system emits four of the greenhouse gases associated with climate change: carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and chlorofluorocarbons.[1] The burning of fossil fuels (such as oil and gasoline) to power vehicles that transport food for long distances by air, ship, truck and rail releases carbon dioxide (CO2), the primary gas responsible for global warming. Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) are emitted from mechanical refrigerating and freezing mechanisms – both staples in food shipment and storage.[2] Anthropogenic methane emission sources include agriculture (ruminants, manure management, wetland rice production), various other industries and landfills. Anthropogenic nitrous oxide sources include fertilizer, manure, crop residues and nitrogen-fixing crops production.[3] Methane and nitrous oxide are also emitted in large amounts from natural sources. The 100-year global warming potentials of methane and nitrous oxide are recently estimated at 25 and 298 carbon dioxide equivalents, respectively.[4]

Steinfeld et al. estimate that livestock production accounts for 18 percent of anthropogenic GHG emissions expressed as carbon dioxide equivalents.[5] Of this amount, 34 percent is carbon dioxide emission from deforestation, principally in Central and South America, that they assigned to livestock production. However, deforestation associated with livestock production is not an issue in many regions. In the US, the land area occupied by forest increased between 1990 and 2009[6] and a net increase in forest land area was also reported in Canada.[7]

Of emissions they attribute to livestock production, Steinfeld et al. estimate that globally, methane accounts for 30.2 percent. Like other greenhouse gases, methane contributes to global warming when its atmospheric concentration rises. Although methane emission from agriculture and other anthropogenic sources has contributed substantially to past warming, it is of much less significance for current and recent warming. This is because there has been relatively little increase in atmospheric methane concentration in recent years[8][9][10][11] The anomalous increase in methane concentration in 2007, discussed by Rigby et al., has since been attributed principally to anomalous methane flux from natural wetlands, mostly in the tropics, rather than to anthropogenic sources.[12]

Livestock sources (including enteric fermentation and manure) account for about 3.1 percent of US anthropogenic GHG emissions expressed as carbon dioxide equivalents.[3] This EPA estimate is based on methodologies agreed to by the Conference of Parties of the UNFCCC, with 100-year global warming potentials from the IPCC Second Assessment Report used in estimating GHG emissions as carbon dioxide equivalents.

A 2016 study published in Nature Climate Change concludes that climate taxes on meat and milk would simultaneously produce substantial cuts in greenhouse gas emissions and lead to healthier diets. Such taxes would need to be designed with care: exempting and subsidising some food groups, selectively compensating for income loss, and using part of the revenue for health promotion. The study analyzed surcharges of 40% on beef and 20% on milk and their effects on consumption, climate emissions, and distribution. An optimum plan would reduce emissions by 1 billion tonnes per year – similar in amount to those from aviation globally.[13][14]

High-carbon and low-carbon food choices

[edit]

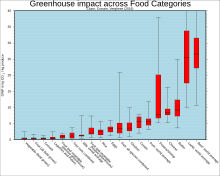

Certain foods require more fossil fuel inputs than others, making it possible to go on a low-carbon diet and reduce one’s carbon footprint by choosing foods that need less fossil fuel and therefore emit less carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.[citation needed]

In June 2010, a report from United Nations Environment Programme declared that a global shift towards a vegan diet was needed to save the world from hunger, fuel shortages and climate change.[16]

Cundiff and Harris[17] write: "The American Dietetic Association (ADA) and Dietitians of Canada position paper officially recognizes that well-planned vegan and other vegetarian diets are appropriate for infancy and childhood.[18]"

China introduced new dietary guidelines in 2016 which aim to cut meat consumption by 50% and thereby reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 1 billion tonnes by 2030.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ STAT saying that those four are emitted

- ^ CFC STAT

- ^ a b EPA. 2011. Inventory of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and sinks: 1990-2009. United States Environmental Protection Agency. EPA 430-R-11-005. 459 pp.

- ^ IPCC. 2007. Fourth Assessment Report. The Scientific Basis. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Sec. 2.10.2.

- ^ Steinfeld, H. et al. 2006, Livestock’s Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options. Livestock, Environment and Development, FAO.

- ^ US EPA. 2011. Inventory of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and sinks: 1990-2009. United States Environmental Protection Agency. EPA 430-R-11-005. 459 pp.

- ^ Environment Canada. 2010. National Inventory Report 1990-2008. Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada. Part 1. 221 pp.

- ^ Dlugokencky, E. J.; et al. (1998). "Continuing decline in the growth rate of the atmospheric methane burden". Nature. 393 (6684): 447–450. Bibcode:1998Natur.393..447D. doi:10.1038/30934. S2CID 4390669.

- ^ Dlugokencky, E.J.; et al. (2011). "Global atmospheric methane: budget, changes and dangers". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 369 (1943): 2058–2072. Bibcode:2011RSPTA.369.2058D. doi:10.1098/rsta.2010.0341. PMID 21502176.

- ^ IPCC. 2007. Fourth Assessment Report. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- ^ Rigby, M.; et al. (2008). "Renewed growth of atmospheric methane" (PDF). Geophys. Res. Lett. 35 (22): L22805. Bibcode:2008GeoRL..3522805R. doi:10.1029/2008GL036037. hdl:1983/0b493e8e-0ef3-4d9f-9994-84ce0e4bc8f0. S2CID 18219105.

- ^ Bousquet, P.; et al. (2011). "Source attribution of the changes in atmospheric methane for 2006-2008". Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11 (8): 3689–3700. Bibcode:2011ACP....11.3689B. doi:10.5194/acp-11-3689-2011.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (7 November 2016). "Tax meat and dairy to cut emissions and save lives, study urges". The Guardian. London, United Kingdom. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ^ Springmann, Marco; Mason-D'Croz, Daniel; Robinson, Sherman; Wiebe, Keith; Godfray, H Charles J; Rayner, Mike; Scarborough, Peter (7 November 2016). "Mitigation potential and global health impacts from emissions pricing of food commodities". Nature Climate Change (1): 69. Bibcode:2017NatCC...7...69S. doi:10.1038/nclimate3155. ISSN 1758-678X. S2CID 88921469.

- ^ Stephen Clune; Enda Crossin; Karli Verghese (1 January 2017). "Systematic review of greenhouse gas emissions for different fresh food categories" (PDF). Journal of Cleaner Production. 140 (2): 766–783. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.04.082.

- ^ Felicity Carus UN urges global move to meat and dairy-free diet, The Guardian, 2 June 2010

- Also see "Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Consumption and Production", United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Brussels, 2 June 2010.

- ^ Cundiff, David K.; Harris, William (2006). "Case report of 5 siblings: malnutrition? Rickets? DiGeorge syndrome? Developmental delay?". Nutrition Journal. 5: 1. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-5-1. PMC 1363354. PMID 16412249.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ American Dietetic Association (2003). "Position of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada: Vegetarian diets". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 103 (6): 748–765. doi:10.1053/jada.2003.50142. PMID 12778049.

- ^ Milman, Oliver (20 June 2016). "China's plan to cut meat consumption by 50% cheered by climate campaigners". The Guardian. Retrieved 2016-06-20.