User:DVSnell/Takizawa Bakin

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

DVSnell/Takizawa Bakin | |

|---|---|

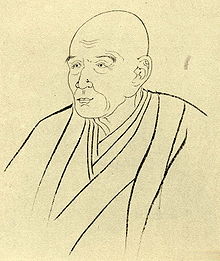

Bakin's portrait by Kunisada (国貞) | |

| Born | Takizawa Bakin 4 July 1767 Fukagawa, Edo, Japan |

| Died | 1 December 1848 (aged 81) Shinano Hill, Japan |

| Resting place | Jinkōji Temple, Tokyo, Japan |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse |

Aida Ohyaku (m. 1793–1841) |

| Children |

|

Takizawa Bakin (曲亭 馬琴), a.k.a. Kyokutei Bakin (曲亭 馬琴, 4 July 1767 – 1 December 1848), was a Japanese novelist of the Edo period. Born Takizawa Okikuni (滝沢興邦), he wrote under the pen name Kyokutei Bakin (曲亭馬琴). Later in life he took the pen name Toku (解). Modern scholarship generally refers to him as Kyokutei Bakin, or just as Bakin. He is regarded as one of, if not the, leading author of early 19th century Japanese literature[1]. He was the third surviving son of a Samurai family of low rank. After numerous deaths in his family, he relinquished his samurai status, married a merchant's widow, and became an Edo townsperson. He was able to support his family with his prolific writing of gesaku,[2] primarily didactic historical romances, though he always wanted to restore his family to the samurai social class.[3] Some of his best known works are Nansō satomi hakkenden (The Chronicles of the Eight Dog Heroes of the Satomi Clan of Nansō) consisting of 106 books[4] and Chinsetsu yumiharizuki (Strange Tales of the Crescent Moon). Bakin published more than 200 works in his life, including literary critiques, diaries, and historical novels.

Life and Career

[edit]Family and Early Life

[edit]Born in Edo (present-day Tokyo) on 4 July 1767, Bakin was the fifth son of Bunkurō Omon and Takizawa Okiyoshi. Two of his elder brothers died in infancy.

Bakin's father, Okiyoshi, was a samurai in the service of one of the Shōgun's retainers, Matsudaira Nobutsuna until 1751 when he left his lord and gained service with Matsuzawa Bunkurō. While serving under Bunkurō, Okiyoshi was adopted into the family and wed Bunkurō's adopted daughter, Omon. Okiyoshi returned to serve the Matsudaira family in 1760 after Okiyoshi's successor was dismissed for embezzlement. Though a heavy drinker, he was devoted to scholarship of classical Chinese works, especially those focused on military matters. He was a diligent samurai, but contracted gout in 1773 and died in 1775. His death forced the Matsudaira clan to reduce the Takizawa stipend by half, starting the steady decline of Bakin's family.

Omon, Bakin's mother, is characterized as being a good mother and loyal wife and the family had the privilege of living in the Matsudaira mansion until their piecemeal departure from Matsudaira Nobunari's service that reached it's completion in 1780. Her eldest son, Rabun (1759-1798) was the only child not born on the Matsudaira estate and served the family until becoming a rōnin in 1776. His departure led to Omon and her remaining children including Bakin and his two younger sisters, Ohisa (1771-?) and Okiku (1774-?), being forced into a much smaller dwelling. Bakin's older brother, Keichū (1765–1786),was adopted out to lessen the financial burden and Bakin was declared the head of the family at age nine.[3] When Rabun found service with a new family in 1778, Omon pretended to be ill to move in with him. While living there, Omon grew ill due to malnutrition and died 1 August 1785.[3]

Bakin served the Matsudaira lord's grandson until 1780 when he declared himself rōnin at age 14. Rabun was able to secure a position for him in 1781, the longest Bakin would hold, until he departed in 1784 due to dissatisfaction. Bakin then moved in with Keichū for a short time until Keichū's lord died, discharging him from service in 1785. He found a position for Bakin, though the young samurai stayed on for less than a year. Keichū died unattended in September 1786.

Keichū's death humbled Bakin who became ill in 1788. He left his post as a samurai and moved in with Rabun who had spent most of his savings on medicine. This was the last time Bakin would serve as a samurai. He would study medicine but find the profession uncomfortable before pursuing jobs as a comic poet, fortuneteller, comedian, and Confucian Scholar.[5] Bakin's turning point came in 1790 when he approached the very successful author, Santō Kyōden, seeking help with the publication of the former samurai's first work, Tsukaihatashite nibu kyogen (尽用而二分狂言).[6]

In 1798 Rabun died of dysentery leaving Bakin as the sole male heir of the Takizawa line. He swore to restore the family line. Rabun's two daughters had died of illness in infancy.

Life as an Author

[edit]Tsukaihatashite nibu kyogen (尽用而二分狂言) was published in 1791 under the pen name "Daiei Sanjin, Disciple of Kyoden". This first book had a didactic tone that Bakin would carry through most of his works going forward. This choice in tone would benefit him as literature and the laws around it had changed in 1790 with the adoption of the Kansei Reforms. Bakin was able to avoid the punishments levied on his contemporaries like Shikitei Sanba, Jippensha Ikku and his friend and patron, Santō Kyōden. Bakin chose to stay silent and on any controversies in his writings. Kyōden's own humiliation deeply affected him. He request Bakin ghostwrite for him as a deadline for two works approached. These two works, Tatsunomiyako namagusa hachinoki and Jitsugo-kyō osana kōshaku were written by Bakin and copied by Kyōden before being sent off for publishing.[3] 1792 marked the first time "Bakin" appeared in a published work.

In 1793 Bakin married Aida Ohyaku, a widow and owner of a footwear shop, mainly for financial reasons. Ohyaku gave Bakin four children during their marriage: three daughters; Osaki (1794-1854), Oyū (1796-?) and Okuwa (1800-?), and one son, Sōhaku (1798-1835). Bakin helped with the shop until the death of his mother-in-law in 1795 when he acquired time to write more regularly. In 1796, he published his first yomihon Takao senjimon (高尾船字文) and his works spread to Kyoto and Osaka, earning him nationwide acclaim. He had eleven other works published in 1797, setting a pace of about ten books per year until 1802. If he wrote a story he didn't enjoy, he would sign it "Kairaishi, disciple of Kyokutei Bakin" causing other aspiring authors to seek out this fictional disciple.[3]

In 1800 Bakin embarked on a walking tours and his experiences would play pivotal roles in both his life and writing. The first tour lasted two months and provided him with several historical locations that would appear in his works. During this trip he also fully resolved to restore his family position using his writing.

A second walking tour in 1802 lasted three months and was a tour along the Tōkaidō Post Road. On this tour, Bakin visited many places that would appear in his future work. He also encountered people of various social standing and professions. His travels coincided with extensive flooding across the nation. Bakin witnessed recent destruction and displaced peoples all along the road. These encounters and experiences made their way into Bakin's novels and lent them an honesty that would make his works popular through the entire social strata of Japan.[3]

From 1803 to 1813, Bakin published thirty historical novels, marking the beginning of his full career as a professional writer. Several of these works were adapted to various forms of theater across Japan. By 1810 Bakin was making a comfortable living as a writer, exceeding the stipend that had been allotted to his family while they served under Matsudaira and he was considered the preeminent author of historical novels.[3]

This success was partly due to his collaboration with famous artists. Between 1804 and 1815, Bakin and the creative illustrator Hokusai collaborated on 13 works. In particular, Chinsetsu yumiharizuki, published between 1807 and 1811, which borrowed the concept of The Tale of Hōgen, Taiheiki and Water Margin. By 1818, with the purchase of a second household with the profits of his book sales and wife's business, the Takizawa family was officially restored. In 1820, Bakin's son, Sōhaku was appointed clan physician by Lord Matsumae Akihiro making his social class officially samurai and Bakin felt his family's future was secured.

The Bunka-Bunsei cultural renaissance which started in 1804 lent momentum to fiction as a whole and art flourished until the renaissance concluded around 1830. Serialized long-form works became more prevalent, not just among historical novels. It was during this time that Bakin continued publishing profitable and popular works. These ranged among scholarly essays and journals, though his most prevalent fiction remained the historical novel. He also embarked on creating his signature piece, Nansō satomi hakkenden. This work consisted of 106 volumes, making it one of the world's longest novels, and took 28 years to complete (1814–1842). Like most of his works, Hakkenden focused on samurai themes, including loyalty and family honor, as well as Confucianism, and Buddhist philosophy. During it's production, Bakin would recede from public life and split from his contemporaries causing rumors to circulate that he had died. Unfortunately, while working on this voluminous work, Bakin would experience the loss of his eyesight and the death of his wife and only son.

Decline and Death

[edit]While writing, Bakin also went about ensuring his children married well. Oyu had married in 1815 and given birth to a son. Osaki married Yoshida Shinroku (1787-1837) in 1823 and her new husband took on the management of the family business under the name Seiemon. Sōhaku, after a prolonged illness that kept him from his duties as a clan physician, married a young woman named Otetsu in 1827. She was later called Omichi and would play a pivotal role in her father-in-law's later life. Omichi bore three children; son Tarō (1828-?), daughter Otsugi (1830-?) who was adopted by Osaki and Seiemon, and daughter Osachi (1833-?). The final parts of the work were dictated to his daughter-in-law.

Bakin's health, which had started a slow decline in 1818 worsened into the 1830s. He continued to publish but at a much slower pace than before. His wife's frequent illnesses taxed him as did his son's continued invalidity and Bakin's rheumatism and vision loss progressed. He would feel bouts of energy between 1825 and 1835 that would allow him to continue working.[3] In 1835, Sōhaku passed and the blow was so devastating to Bakin that he considered retiring from writing.

Fearing the collapse of his newly-restored family, Bakin decided in 1836 to hold a party to celebrate his birthday. In reality, he did so to raise funds for Tarō to afford a position as a low-ranking samurai. The gala attracted leading writers and publishers, poets and entertainers, and important officials form the Shōgun's court. Tarō's future was secured though he was too young to serve at the time. Omichi's cousin served in his place until 1840 under the name Takizawa Jirō. In order to be closer to his grandson's post, Bakin sold the family house in the city and moved into a rural estate. He would spend the last twelve years of his life there.

Bakin lost vision in his right eye in 1834 and was completely blind by 1840. Omichi, who could read complex literature acted as Bakin's amanuensis from 1840 till his death in 1848. With her assistance he finished several works and answered many letters and critiques. She also attended to the house as Ohyaku had slipped into mental instability with the death of Sōhaku. Aida Ohyaku died in 1841.[3]

In the autumn of 1848, Bakin felt chest pains and had difficulty breathing. After a short recovery he relapsed and declined the services of a physician. On November 30th, he gave his final testament and passed early in the morning of December 1st. He was interred in the Jinkōji Temple beside his ancestors.[3]

Influence on Japanese Culture

[edit]Nearly four decades after his death, Bakin's works were still popular. Many writers, such as Kanagaki Robun kept his works in the public eye. There was, however, push back from students who had become versed in Western literature. Foremost among them was Tsubouchi Shōyō who heavily criticized Bakin's didactic method of writing as pre-modern without directly attacking Bakin in his work Shōsetsu shinzui.[2] This attitude was countered by scholars like Yoda Gakkai.

Mori Ōgai and similar authors used Bakin's methodology for adapting Chinese literature to bring Western works to Japan.

A series of ukiyo-e containing 50 pictures depicting characters from Nansō Satomi Hakkenden and featuring leading kabuki actors was created by Utagawa Kunisada II. These prints were published in the early 1850s by Tsutaya Kichizo.[7] Excerpts translated by Chris Drake are included in Early Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology, 1600-1900, edited by Haruo Shirane (Columbia University Press, 2002). The Eight Dog Chronicles has been adapted many times in, for example, the anime OVA The Hakkenden.

His Chinsetsu Yumiharizuki (Strange Tales of the Crescent Moon) was adapted for the kabuki stage by Yukio Mishima.

Sample Bibliography

[edit]Yomihon (Readers' Books)

[edit]- 高尾船字文 (Takao senjimon) 1796

- 小説比翼文 (Shōsetsu hiyokumon)1804

- 曲亭伝奇花釵児 (Kyokutei denki hanakanzashi)1804

- 復讐月氷奇縁 (Kataki uchigeppyō kien) 1804 (Volume 1 and 2)

- 復讐奇譚稚枝鳩 (Fukushūkidan wakae no hato) 1805

- 源家勲績 四天王剿盗異録 (Genke-kun sekishten no usōtōiroku) 1805

- 小夜中山復讐 石言遺響 (Sayonokayama fukushū sekigenikyō) 1804

- 新編水滸画伝 (Shinpen suikogaden) 1805

- 新累解脱物語 (Shinkasane gedatsu monogatari) 1807

- 椿説弓張月 (Chinsetsu yumiharitzuki) 1807-1811

- 三七全伝南柯夢 (Sanshichi zenden nanka no yume) 1808

- 雲妙間雨夜月 (Kumono taema amayo no tsuki) 1808

- 頼豪阿闍梨恠鼠伝 (Raigō ajarikaisoden) 1808

- 松浦佐用姫石魂録 (Matsura sayohime sekikon roku) 1808

- 俊寛僧都嶋物語 (Shunkan sōzushima monogatari) 1808

- 旬伝実々記 (Junden jitsujitsuki) 1808

- 松染情史秋七草 (Shōsen jōshi aki no nanakusa) 1809

- 夢想兵衛胡蝶物語 (Musō byōekochō monogatari) 1810

- 南総里見八犬伝 (Nansō satomi hakkenden) 1814-1842

- 朝夷巡島記 (Asahi nashima meguri no Ki) 1815 (Volume 1 Unfinished)

- 近世説美少年録 (Kinse setsu bishōnen roku) 1829-1830(Bunsei 12 and 13)

- 開巻驚奇侠客伝 (Kaikan kyōki kyōkakuden) 1832 (Unfinished)

Gōkan

[edit]- 青砥藤綱摸稜案 (Aoto fujitsuna moryōan) 1812

- 傾城水滸伝 (Kēsē suikoden) 1825 (Unfinished)

- 風俗金魚伝 (Fūzoku kingyoden) 1839

- 新編金瓶梅 (Shinpenkinpēbai) 1831

Yellow Books

[edit]- 廿日余四十両尽用二分狂言 (Tsukaihatashite nibu kyōgen) 1791

- 无筆節用似字尽 (Muhitsu yōnita jitzukushi) 1797

- 化競丑満鐘 (Bakekurabeushitsu no kane) 1800

- 曲亭一風京伝張 (Kyokutei ippūkyodenbari) 1801

Saijiki (Seasonal Dictionary)

[edit]- 俳諧歳時記 (Haiku saijiki) 1803 The first "Haiku saijiki"[[

References

[edit]- ^ Zolbrod, Leon (1966). "Yomihon: The Appearance of the Historical Novel in Late Eighteenth Century and Early Nineteenth Century Japan". The Journal of Asian Studies. 25 (3): 485–498. doi:10.2307/2052003. ISSN 0021-9118.

- ^ a b Ueda, Atsuko (2005). "The Production of Literature and the Effaced Realm of the Political". The Journal of Japanese Studies. 31 (1): 61–88. doi:10.1353/jjs.2005.0029. ISSN 1549-4721.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Zolbrod, Leon M., (1967). Takizawa Bakin. New York: Twayne Publishers, Inc. LCCN 67-12269. OCLC 625222.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 滝沢馬琴墓(深光寺) Bunkyō, Tokyo

- ^ Atherton, David C. (2020). "The Author as Protagonist: Professionalizing the Craft of the Kusazōshi Writer". Monumenta Nipponica. 75 (1): 45–89. doi:10.1353/mni.2020.0001. ISSN 1880-1390.

- ^ Kotobank. Takizawa Bakin. The Asahi Shimbun.

- ^ Catalogue: Chiba Museum, Hakkenden no sekai (2008).