User:Crazynas/sandbox

| This is the sandbox of Crazynas. A sandbox is a subpage of a userpage (like this one) or a article used to test a change to the main article or be a brain dump for later edits. Once you have finished with the test, please Or try other sandboxes (no, really they're way more fun then mine): Main Sandbox | Tutorial Sandbox 1 | Tutorial Sandbox 2 | Tutorial Sandbox 3 | Tutorial Sandbox 4 | Tutorial Sandbox 5

|

Working Area

[edit]Summary

[edit]

The first part of Don Quixote was published in 1605, divided internally into four parts, not the first part of a two-part set. The mention in the 1605 book of further adventures yet to be told was totally conventional, does not indicate any authorial plans for a continuation[citation needed], and was not taken seriously by the book's first readers.[1] Although the two parts are now published as a single work, Don Quixote, Part Two was a sequel published ten years after the original novel. While Part One was mostly farcical, the second half is more serious and philosophical about the theme of deception and "sophistry". Opening just prior to the third Sally, the first chapters of Part Two show Don Quixote found to be still some sort of a modern day "highly" literate know-it-all, knight errant.Part Two of Don Quixote explores the concept of a character understanding that he is written about, an idea much explored in the 20th century. As Part Two begins, it is assumed that the literate classes of Spain have all read the first part of the story. Cervantes' meta-fictional device was to make even the characters in the story familiar with the publication of Part One, as well as with an actually published, fraudulent Part Two.

Part 1 (1605)

[edit]Cervantes wrote that the first chapters were taken from "the archives of La Mancha", and the rest were translated from an Arabic text by the Moorish historian Cide Hamete Benengeli. This metafictional trick to give a greater credibility to the text, implying that Don Quixote is a real character and that this has been researched from the logs of the events that truly occurred several decades prior to the recording of this account.

The First Sally (Chapters 1–5)

[edit]Alonso Quixano, the protagonist of the novel (though he is not given this name until much later in the book), is a hidalgo (member of the lesser Spanish nobility), nearing 50 years of age, living in an unnamed section of La Mancha with his niece and housekeeper, as well as a stable boy who is never heard of again after the first chapter. Although Quixano is usually a rational man, in keeping with the humoral physiology theory of the time, not sleeping adequately—because he was reading—has caused his brain to dry. Quixano's temperament is thus choleric, the hot and dry humor. As a result, he is easily given to anger[2] and believes every word of some of these fictional books of chivalry to be true such were the "complicated conceits"; "what Aristotle himself could not have made out or extracted had he come to life again for that special purpose".

"He commended, however, the author's way of ending his book with the promise of that interminable adventure, and many a time was he tempted to take up his pen and finish it properly as is there proposed, which no doubt he would have done...". Having "greater and more absorbing thoughts", he reaches imitating the protagonists of these books, and he decides to become a knight errant in search of adventure. To these ends, he dons an old suit of armor, renames himself "Don Quixote", names his exhausted horse "Rocinante", and designates Aldonza Lorenzo, intelligence able to be gathered of her perhaps relating that of being a slaughterhouse worker with a famed hand for salting pigs, as his lady love, renaming her Dulcinea del Toboso, while she knows nothing of this. Expecting to become famous quickly, he arrives at an inn, which he believes to be a castle, calls the prostitutes he meets "ladies" (doncellas), and demands that the innkeeper, whom he takes to be the lord of the castle, dub him a knight. He goes along with it (in the meantime convincing Don Quixote to take to heart his need to have money and a squire and some magical cure for injuries) and having morning planned for it. Don Quixote starts the night holding vigil over his armor and shortly becomes involved in a fight with muleteers who try to remove his armor from the horse trough so that they can water their mules. In a pretended ceremony, the innkeeper dubs him a knight to be rid of him and sends him on his way right then.

Don Quixote next "helps" a servant named Andres who is tied to a tree and beaten by his master over disputed wages, and makes his master swear to treat him fairly, but in an example of transference his beating is continued (and in fact redoubled) as soon as Quixote leaves (later explained to Quixote by Andres). Don Quixote then encounters traders from Toledo, who "insult" the imaginary Dulcinea. He attacks them, only to be severely beaten and left on the side of the road, and is returned to his home by a neighboring peasant.

Destruction of Don Quixote's library (Chapters 6–7)

[edit]While Don Quixote is unconscious in his bed, his niece, the housekeeper, the parish curate, and the local barber burn most of his chivalric and other books. A large part of this section consists of the priest deciding which books deserve to be burned and which to be saved. It is a scene of high comedy: If the books are so bad for morality, how does the priest know them well enough to describe every naughty scene? Even so, this gives an occasion for many comments on books Cervantes himself liked and disliked. For example, Cervantes' own pastoral novel La Galatea is saved, while the rather unbelievable romance Felixmarte de Hyrcania is burned. After the books are dealt with, they seal up the room which contained the library, later telling Don Quixote that it was the action of a wizard (encantador).

The Second Sally (Chapters 8–10)

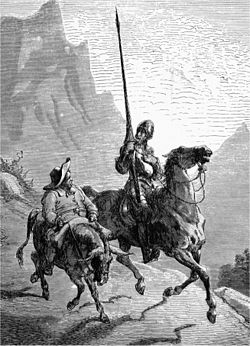

[edit]After a short period of feigning health, Don Quixote requests his neighbour, Sancho Panza, to be his squire, promising him a petty governorship (ínsula). Sancho is a poor and simple farmer but more practical than the head-in-the-clouds Don Quixote and agrees to the offer, sneaking away with Don Quixote in the early dawn. It is here that their famous adventures begin, starting with Don Quixote's attack on windmills that he believes to be ferocious giants.

The two next encounter two Benedictine friars travelling on the road ahead of a lady in a carriage. The friars are not traveling with the lady, but happen to be travelling on the same road. Don Quixote takes the friars to be enchanters who hold the lady captive, knocks a friar from his horse, and is challenged by an armed Basque traveling with the company. As he has no shield, the Basque uses a pillow from the carriage to protect himself, which saves him when Don Quixote strikes him. Cervantes chooses this point, in the middle of the battle, to say that his source ends here. Soon, however, he resumes Don Quixote's adventures after a story about finding Arabic notebooks containing the rest of the story by Cid Hamet Ben Engeli. The combat ends with the lady leaving her carriage and commanding those traveling with her to "surrender" to Don Quixote.

The Pastoral Peregrinations (Chapters 11–15)

[edit]Sancho and Don Quixote fall in with a group of goatherds. Don Quixote tells Sancho and the goatherds about the age "...to which the ancients gave the name golden..." A lively Garden of Eden telling. Impressed the goatherds try to return the favor to Don Quixote and in the process apply an herb bandage to his ear that "proved" to work. The goatherds invite the Knight and Sancho to the funeral of Chrysóstomo "...that famous student-shepherd..." who had a renowned predictive ability. A longtime student who left his studies to become a shepherd after returning to his home village and first seeing the shepherdess Marcela (the spot where he's to be buried at his request). Marcela a now famous beauty with many seeking after her while she one day joined into the local shepherd community. At the funeral Marcela appears - vindicating herself as the victim of a bad one-sided affair and from the bitter verses written about her by Chrysóstomo claiming she's just satisfied by her communing with nature now and is assuming her own autonomy and freedom from expectations put on. She disappears into the woods, and Don Quixote and Sancho follow. Ultimately giving up, the two dismount by a stream to rest. "A drove of Galician ponies belonging to certain Yanguesan carriers" are planned to feed there, and Rocinante (Don Quixote's horse) attempts to mate with the ponies. The carriers hit Rocinante with clubs to dissuade him, whereupon Don Quixote tries to defend Rocinante. The carriers beat Don Quixote and Sancho, leaving them in great pain.

The Inn (Chapters 16–17)

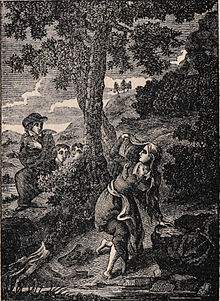

[edit]After escaping the Yanguesan carriers, Don Quixote and Sancho ride to a nearby inn. Once again, Don Quixote imagines the inn is a castle, although Sancho is not quite convinced. Don Quixote is given a bed in a former hayloft, and Sancho sleeps on the rug next to the bed; they share the loft with a carrier. When night comes "... he began to feel uneasy and to consider the perilous risk which his virtue was about to encounter...". Don Quixote imagines the servant girl at the inn, Maritornes, to be this imagined beautiful princess now fallen in love with him "... and had promised to come to his bed for a while that night...", and makes her sit on his bed with him by holding her "... besides, to this impossibility another yet greater is to be added...". Having been waiting for Maritornes and seeing her held while trying to get free the carrier attacks Don Quixote "...and jealous that the Asturian should have broken her word with him for another...", breaking the fragile bed and leading to a large and chaotic fight in which Don Quixote and Sancho are once again badly hurt. Don Quixote's explanation for everything is that they fought with an enchanted Moor. He also believes that he can cure their wounds with a mixture he calls "the balm of Fierabras", which only makes Sancho so sick that he should be at death's door. Don Quixote's not quite through with it yet, however, as his take on things can be different. Don Quixote and Sancho decide to leave the inn, but Quixote, following the example of the fictional knights, leaves without paying. Sancho, however, remains and ends up wrapped in a blanket and tossed up in the air (blanketed) by several mischievous guests at the inn, something that is often mentioned over the rest of the novel. After his release, he and Don Quixote continue their travels.

The galley slaves and Cardenio (Chapters 19–24)

[edit]

After Don Quixote has adventures involving a dead body, a helmet (to Don Quixote), and freeing a group of galley slaves, he and Sancho wander into the Sierra Morena and there encounter the dejected and mostly mad Cardenio. Cardenio relates the first part of his story, in which he falls mutually in love with his childhood friend Lucinda, and is hired as the companion to the Duke's son, leading to his friendship with the Duke's younger son, Don Fernando. Cardenio confides in Don Fernando his love for Lucinda and the delays in their engagement, caused by Cardenio's desire to keep with tradition. After reading Cardenio's poems praising Lucinda, Don Fernando falls in love with her. Don Quixote interrupts when Cardenio's transference of his misreading suggests his madness, over that his beloved may have become unfaithful, stems from Queen Madasima and Master Elisabad relationship in a chivalric novel (Lucinda and Don Fernando not at all the case, also). They get into a physical fight, ending with Cardenio beating all of them and walking away to the mountains.

The priest, the barber, and Dorotea (Chapters 25–31)

[edit]Quixote pines over Dulcinea's lack of affection ability, imitating the penance of Beltenebros. Quixote sends Sancho to deliver a letter to Dulcinea, but instead Sancho finds the barber and priest from his village and brings them to Quixote. The priest and barber make plans with Sancho to trick Don Quixote to come home. They get the help of the hapless Dorotea, an amazingly beautiful woman whom they discover in the forest that has been deceived with Don Fernando by acts of love and marriage, as things just keep going very wrong for her after he had made it to her bedchamber one night "...by no fault of hers, has furnished matters..." She pretends that she is the Princess Micomicona and coming from Guinea desperate to get Quixote's help with her fantastical story, "Which of the bystanders could have helped laughing to see the madness of the master and the simplicity of the servant?" Quixote runs into Andrés "...the next moment ran to Don Quixote and clasping him round the legs..." in need of further assistance who tells Don Quixote something about having "...meddled in other people's affairs...".

Return to the inn (Chapters 32–42)

[edit]Convinced that he is on a quest to first return princess Micomicona to the throne of her kingdom before needing to go see Dulcinea at her request (a Sancho deception related to the letter Sancho says he's delivered and has been questioned about), Quixote and the group return to the previous inn where the priest reads aloud the manuscript of the story of Anselmo (The Impertinently Curious Man) while Quixote, sleepwalking, battles with wine skins that he takes to be the giant who stole the princess Micomicona's kingdom to victory, "there you see my master has already salted the giant." A stranger arrives at the inn accompanying a young woman. The stranger is revealed to be Don Fernando, and the young woman Lucinda. Dorotea is reunited with Don Fernando and Cardenio with Lucinda. "...it may be by my death he will be convinced that I kept my faith to him to the last moment of life." "...and, moreover, that true nobility consists in virtue, and if thou art wanting in that, refusing what in justice thou owest me, then even I have higher claims to nobility than thine." A Christian captive from Moorish lands in company of an Arabic speaking lady (Zoraida) arrive and the captive is asked to tell the story of his life; "If your worships will give me your attention you will hear a true story which, perhaps, fictitious one constructed with ingenious and studied art can not come up to." "...at any rate, she seemed to me the most beautiful object I had ever seen; and when, besides, I thought of all I owed to her I felt as though I had before me some heavenly being come to earth to bring me relief and happiness." A judge arrives travelling with his beautiful and curiously smitten daughter, and it is found that the captive is his long-lost brother, and the two are reunited as Dona Clara's (his daughter's name) interest arrives with/at singing her songs from outside that night. Don Quixote's explanation for everything now at this inn being "chimeras of knight-errantry". A prolonged attempt at reaching agreement on what are the new barber's basin and some gear is an example of Quixote being "reasoned" with. "...behold with your own eyes how the discord of Agramante's camp has come hither, and been transferred into the midst of us." He goes on some here to explain what he is referring to with a reason for peace among them presented and what's to be done. This works to create peacefulness for them but the officers, present now for a while, have one for him that he can not get out of though he goes through his usual reactions.

The ending (Chapters 45–52)

[edit]An officer of the Santa Hermandad has a warrant for Quixote's arrest for freeing the galley slaves "...as Sancho had, with very good reason, apprehended." The priest begs for the officer to have mercy on account of Quixote's insanity. The officer agrees, and Quixote is locked in a cage and made to think that it is an enchantment and that there is a prophecy of him returned home afterwards that's meaning pleases him. He has a learned conversation with a Toledo canon (church official) he encounters by chance on the road, in which the canon expresses his scorn for untruthful chivalric books, but Don Quixote defends them with an adventure to the otherworld. The group stops to eat and lets Don Quixote out of the cage; he gets into a fight with a goatherd (Leandra transferred to a goat) and with a group of pilgrims (tries to liberate their image of Mary), who beat him into submission, and he is finally brought home. The narrator ends the story by saying that he has found manuscripts of Quixote's further adventures.

Part 2

[edit]

The Third Sally

[edit]The narrator relates how Hamet Benengeli begins the eighth chapter with thanksgivings to Allah at having Don Quixote and Sancho "fairly afield" now (and going to El Toboso). Traveling all night, some religiosity and other matters are expressed between Don Quixote and Sancho with Sancho getting at that he thinks they should be better off by being "canonized and beatified." They reach the city at daybreak and it's decided to enter at nightfall, with Sancho aware that his Dulcinea story to Don Quixote was a complete fabrication (and again with good reason sensing a major problem); "Are we going, do you fancy, to the house of our wenches, like gallants who come and knock and go in at any hour, however late it may be?" The place is asleep and dark with the sounds of an intruder from animals heard and the matter absurd but a bad omen spooks Quixote into retreat and they leave before daybreak.

(Soon and yet to come, when a Duke and Duchess encounter the duo they already know their famous history and they themselves "very fond" of books of chivalry plan to "fall in with his humor and agree to everything he said" in accepting his advancements and then their terrible dismount setting forth a string of imagined adventures resulting in a series of practical jokes. Some of them put Don Quixote's sense of chivalry and his devotion to Dulcinea through many tests.)

Now pressed into finding Dulcinea, Sancho is sent out alone again as a go-between with Dulcinea and decides they are both mad here but as for Don Quixote, "with a madness that mostly takes one thing for another" and plans to persuade him into seeing Dulcinea as a "sublimated presence" of a sorts. Sancho's luck brings three focusing peasant girls along the road he was sitting not far from where he set out from and he quickly tells Don Quixote that they are Dulcinea and her ladies-in-waiting and as beautiful as ever, as they get unwittingly involved with the duo. As Don Quixote always only sees the peasant girls "...but open your eyes, and come and pay your respects to the lady of your thoughts..." carrying on for their part, "Hey-day! My grandfather!", Sancho always pretends (reversing some incidents of Part One and keeping to his plan) that their appearance is as Sancho is perceiving it as he explains its magnificent qualities (and must be an enchantment of some sort at work here). Don Quixote's usual (and predictable) kind of belief in this matter results in "Sancho, the rogue" having "nicely befooled" him into thinking he'd met Dulcinea controlled by enchantment, but delivered by Sancho. Don Quixote then has the opportunity to purport that "for from a child I was fond of the play, and in my youth a keen lover of the actor's art" while with players of a company and for him thus far an unusually high regard for poetry when with Don Diego de Miranda, "She is the product of an Alchemy of such virtue that he who is able to practice it, will turn her into pure gold of inestimable worth" "sublime conceptions". Don Quixote makes to the other world and somehow meets his fictional characters, at return reversing the timestamp of the usual event and with a possible apocryphal example. As one of his deeds, Don Quixote joins into a puppet troop, "Melisendra was Melisendra, Don Gaiferos Don Gaiferos, Marsilio Marsilio, and Charlemagne Charlemagne."

Having created a lasting false premise for them, Sancho later gets his comeuppance for this when, as part of one of the Duke and Duchess's pranks, the two are led to believe that the only method to release Dulcinea from this spell (if among possibilities under consideration, she has been changed rather than Don Quixote's perception has been enchanted - which at one point he explains is not possible however) is for Sancho to give himself three thousand three hundred lashes. Sancho naturally resists this course of action, leading to friction with his master. Under the Duke's patronage, Sancho eventually gets a governorship, though it is false, and he proves to be a wise and practical ruler although this ends in humiliation as well. Near the end, Don Quixote reluctantly sways towards sanity.

The lengthy untold "history" of Don Quixote's adventures in knight-errantry comes to a close after his battle with the Knight of the White Moon (a young man from Don Quixote's hometown who had previously posed as the Knight of Mirrors) on the beach in Barcelona, in which the reader finds him conquered. Bound by the rules of chivalry, Don Quixote submits to prearranged terms that the vanquished is to obey the will of the conqueror: here, it is that Don Quixote is to lay down his arms and cease his acts of chivalry for the period of one year (in which he may be cured of his madness). He and Sancho undergo one more prank that night by the Duke and Duchess before setting off. A play-like event, though perceived as mostly real life by Sancho and Don Quixote, over Altisidora's required remedy from death (over her love for Don Quixote). "Print on Sancho's face four-and-twenty smacks, and give him twelve pinches and six pin-thrusts in the back and arms." Altisidora is first to visit in the morning taking away Don Quixote's usual way for a moment or two, being back from the dead, but her story of the experience quickly snaps him back into his usual mode. Some others come around and it is decided to part that day.

"The duped Don Quixote did not miss a single stroke of the count..."; "...beyond measure joyful." A once nearly deadly confrontation for them, on the way back home (along with some other situations maybe of note) Don Quixote and Sancho "resolve" the disenchantment of Dulcinea (being fresh from his success with Altisidora). Upon returning to his village, Don Quixote announces his plan to retire to the countryside as a shepherd (considered an erudite bunch for the most part), but his housekeeper urges him to stay at home. Soon after, he retires to his bed with a deathly illness, and later awakes from a dream, having fully become good. Sancho's character tries to restore his faith and/or his interest of a disenchanted Dulcinea, but the Quexana character ("...will have it his surname..." "...for here there is some difference of opinion among the authors who write on the subject..." "...it seems plain that he was called Quexana.") only renounces his previous ambition and apologizes for the harm he has caused. He dictates his will, which includes a provision that his niece will be disinherited if she marries a man who reads books of chivalry. After the Quexana character dies, the author emphasizes that there are no more adventures to relate and that any further books about Don Quixote would be spurious.

Random interesting templates and tidbits

[edit]

Tidbits

[edit]Policies and guidelines to watch

[edit]Quotes

[edit]There is a fatal flaw in the system. Vandals, trolls and malactors are given respect, whereas those who are here to actually create an encyclopedia, and to do meaningful work, are slapped in the face and not given the support needed to do the work they need to do.

There is no reason to continue here. RickK 04:32, Jun 21, 2005 (UTC)

No, I'm not leaving but it is interesting to consider and I think his words are as relevant now as six years ago.

- [1] - this is an interesting take, by a current arbiter on the 'admin problem'.

- [2] - Trusilver's take on not being an admin any more.

- "Trusilver's scruples are not consistent with the expectations of an administrator, and that he is too principled to suppress his principles for the sake of retaining the bit."Steve Smith (talk) 16:37, 10 March 2010 (UTC) -Arbcom motion to remove Trusilver's bit

- User:Larry Sanger/Origins of Wikipedia self explanatory...

My philosophy on administrators: We're not administrators. We're merely editors with a few extra buttons.User:Shirik

Please also keep in mind that, short of truly egregious administrator behaviour (such as abusive socking, ban evasion, or unblocking oneself to take an administrative action against an opponent), it is nearly impossible for Arbcom to desysop someone short of the community requesting a case before the Committee. I am sure every arbitrator is aware of situations where desysopping would be the likely outcome should a case be brought, but unless someone in the community is willing to bring that case, our hands are pretty much tied. I don't think that's necessarily bad - Arbcom cannot maintain ongoing assessment of the quality of work of all 900 or so active administrators, and the community has pretty clearly indicated over time that it does not like Arbcom to "go looking" for cases, even to the point of concern about cases brought by arbitrators in their personal role. Risker (talk) 16:06, 14 November 2011 (UTC)[3]

Never turn away an idea solely because of its source. Ever. That is an ugly, ugly road to go down, one that leads to utter stagnation and decay. If you disagree with the proposal on its own merits, then that's completely fine. God knows you won't be alone there, and nor should you be; reasoned opposition is the fundamental building block of dispute resolution, and by extension, civilization. But let your opposition stand on its own merits in turn; don't bring ugly partisan politics into it. Writ Keeper 19:56, 15 April 2013 (UTC) [4]

Well, if you've been (correctly) taught not to cite Wikipedia, you're learning... Eventually you will probably come full circle and figure out what Wikipedia's valid functions are: a first step to further investigation of serious topics and a quick and easy way of learning correct answers to questions dealing with the mundane trivia of daily life. User:Carrite (talk) 17:31, 13 June 2013 (UTC)[5]

Misc

[edit]

Templates

[edit]Editorial Templates

[edit]{{cite web}}

[edit]{{cite web |url= |title= |author= |date= |work= |publisher= |accessdate=}}

{{cite journal}}

[edit]{{cite journal |author= |date= |year= |title= |journal= |volume= |issue= |pages= |publisher= |doi= |pmid= |pmc= |url= |accessdate= }}

User Templates

[edit]{{Admin}}

[edit]Crazynas (talk · contribs · blocks · protections · deletions · page moves · rights · RfA)

{{Unsigned2}}

[edit]— Preceding unsigned comment added by Crazynas (talk • contribs) 06:15, 07 December 1941

{{User toolbox|USERNAME}}

[edit]{{Usercheck-full|USERNAME}}

[edit]Crazynas (talk · message · contribs · global contribs · deleted contribs · page moves · user creation · block user · block log · count · total · logs · summary · email | lu · rfa · rfb · arb · rfc · lta · checkuser · spi · socks | rfar · rfc · rfcu · ssp | current rights · rights log (local) · rights log (global/meta) | rights · renames · blocks · protects · deletions · rollback · admin · logs | UHx · AfD · UtHx · UtE)

User:Crazynas Translucion

[edit]

| Crazynas is around sometimes. |

Never turn away an idea solely because of its source. Ever. That is an ugly, ugly road to go down, one that leads to utter stagnation and decay. If you disagree with the proposal on its own merits, then that's completely fine. God knows you won't be alone there, and nor should you be; reasoned opposition is the fundamental building block of dispute resolution, and by extension, civilization. But let your opposition stand on its own merits in turn; don't bring ugly partisan politics into it. Writ Keeper 19:56, 15 April 2013 (UTC) [6]

Alternate Accounts

- ObjectivismLover (talk · message · contribs · count · logs · email) This is my recent changes patrolling (currently using STiki) account.

- CrazynasBot (talk · message · contribs · count · logs · email) This is my fully automated account (which currently has no tasks), the Bot's userpage documents the historical uses.

Under the Hood

[edit]

- ^ Eisenberg, Daniel [in Spanish] (1991) [1976]. "El rucio de Sancho y la fecha de composición de la Segunda Parte de Don Quijote". Estudios cervantinos. Revised version of article first published in es:Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica, vol. 25, 1976, pp. 94-102. Barcelona: Sirmio. ISBN 9788477690375. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- ^ Otis H. Green. "El Ingenioso Hidalgo", Hispanic Review 25 (1957), 175–93.