User:Clairenk/Puyuma sandbox

| Puyuma | |

|---|---|

| 卑南語 | |

| Native to | Taiwan |

| Ethnicity | Puyuma people |

Native speakers | 8,500 (2002)[1] |

Austronesian

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | pyu |

| Glottolog | puyu1239 |

| Linguasphere | 30-JAA-a |

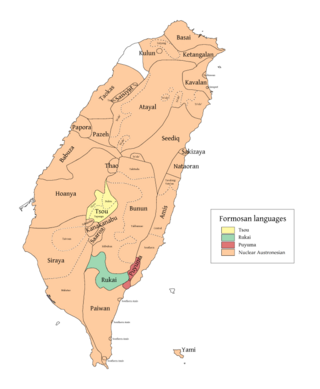

(red) Puyuma | |

The Puyuma language, or Pinuyumayan (Chinese: 卑南語; pinyin: Bēinán Yǔ), is the language of the Puyuma, an indigenous people of southeastern Taiwan (see Taiwanese aborigines). It is a divergent Formosan language of the Austronesian family. Most speakers are older adults.

Puyuma is one of the more divergent of the Austronesian languages and falls outside reconstructions of Proto-Austronesian.

Dialects

[edit]The internal classification of Puyuma dialects below is from (Ting 1978). There are eight dialects of Puyuma that were distinguished by the different villages that spoke these dialects: Nanwang, Katipul, Rikavung, Tamalakaw, Kasavakan, Pinaski, Alipai, and Ulivelivek. Nanwang is usually shown to be the relatively phonologically conservative dialect but grammatically innovative, as it preserves proto-Puyuma voiced plosives but syncretize the use of both oblique and genitive case.[2]: 839, 841 The Nanwang dialect is a level 7 endangered language, according to Ethnologue, which means that it is a shifting language, meaning that children are not learning the language naturally.[3] The Nanwang dialect, specifically, has less than 1000 speakers out of the 10,761 ethnic Puyuma population (not population of native speakers of Puyuma).[4]: 2–3, 5

- Proto-Puyuma

- Nanwang

- (Main branch)

- Pinaski–Ulivelivek

- Rikavung

- Kasavakan–Katipul

Puyuma-speaking villages are:[5]: 655

- Puyuma cluster ('born of the bamboo')

- Katipul cluster ('born of a stone')

- Alipai (Chinese: Pinlang 賓朗)

- Pinaski (Chinese: Hsia Pinlang 下賓朗); 2 km north of Puyuma/Nanwang, and maintains close relations with it

- Pankiu (Chinese: Pankiu)

- Kasavakan (Chinese: Chienhe 建和)

- Katratripul (Chinese: Chihpen 知本)

- Likavung (Chinese: Lichia 利嘉)

- Tamalakaw (Chinese: Taian 泰安)

- Ulivelivek (Chinese: Chulu 初鹿)

Phonology

[edit]Puyuma has 18 consonants and 4 vowels.

Vowels

[edit]There are four vowel phonemes in Puyuma; one front vowel /i/, two central vowels /ə/ and /a/, and one back vowel /u/.[4]: 18

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i | u | |

| Mid | ə (e) | ||

| Low | a |

The mid-rounded vowel [o] is an allophone of the phoneme /u/ when /u/ is followed by a velar or nasal consonant.[4]

The schwa, /ə/, also has phonotactic constraints. One constraint is that after the /s/ phoneme in an open syllable, which is when a vowel is the last sound in the syllable, the schwa is apicalized, i.e. senay --> [sɿnaj] instead of [sənaj].[4]: 22 The other constraint is that the schwa can be deleted in the penultimate syllable of a word with three or more syllables if that syllable is open, i.e. inapetran --> inaptran.[4]: 22

Consonants

[edit]There are 18 consonant phonemes in Puyuma. There are five places of articulation (one multi-place consonant), six manners of articulation, and there are distinctions in voicing.[4]: 11

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voiced Stops | b | d | ɖ | g | ||

| Voiceless Stops | p | t | ʈ | k | ʔ | |

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Voiceless Fricative | s | |||||

| Glides | w | j | ||||

| Lateral | l | ɭ |

Several consonants have phonotactic constraints and change in different circumstances. Examples of these changes are as follows. All voiced stops are not aspirated, while voiceless stops (except the glottal stop) are not aspirated before vowels but then become aspirated when they are word final. For example, /p/ in "pulang" is not aspirated, whereas /p/ in "selap" is aspirated.[4]: 12 The voiceless alveolar fricative, /s/, becomes palatalized, [ʃ], when it is before any high vowel, /i/ or /u/. For example, /siri/ 'goat' --> [ʃiri], and /susu/ 'breast' --> [ʃuʃu], whereas /sagar/ 'like' --> [sagar].[4]: 13 The last rule is that approximants, /w/ and /j/, do not occur before or after a schwa, /ə/.[4]: 13

Syllable Structure

[edit]Puyuma syllable structures can be V, CV, VC, or CVC. Examples are in the chart below and bolded portions correspond to the relevant syllable structure.[4]

| Template | Instantiation | Translation[4]: 20 |

|---|---|---|

| V | /mu.a.sal/ | 'move' |

| CV | /su.an/ | 'dog' |

| VC | /i.ab/ | 'shoulder' |

| CVC | /pe.nuk.puk/ | 'beat (intransitive)' |

There are constraints about how a syllable can be constructed due to phonotactic rules in Puyuma. A schwa, /ə/, cannot form its own syllable (i.e. V structure) and it cannot occur in a word initial or word final position. Monosyllabic words are mostly grammatical markers rather than words from lexical categories, like nouns. Clusters of no more than two consonants are allowed within a word, and the two consonants are never part of the same syllable. Additionally, the syllable structures V.V and VC.CV are not observable. Last, the maximum number of syllables found in a word is eight and if a word have greater than four syllables, then it must be comprised of a stem and at least one affix and/or reduplication.[4]: 21

Stress

[edit]Puyuma has a predictable stress rule in which the stress falls on the last syllable of a word and is marked by increased intensity, higher pitch, and longer duration. For example, beray [bəráj].[4]: 24

The stress rule includes affixes, such that if a suffix is added, the stress will fall on the suffix, however, the rule does not include clitics, such that if a clitic is added to the end of a word, the stress still falls on the last syllable of the main word. For example:

Added affix:

beray --> tu=beray-ay [tubərajáj], the stress is still on the last syllable.

Added enclitic:

inaba [inabá] --> inaba=ku [inabáku], the stress remains on the same syllable as it was before the enclitic was added.[4]: 24

There is a grammatical stress shift in Puyuma. In interrogative sentences, there is a stress shift in the last word of the sentence and the stress is shifted from the last syllable to the second to last syllable. For example:[4]: 221

Interrogative:

kadru=yu

live=2S.NOM

i

LOC

ruma'

house

ma-lrinay

ITR-play

"Did you play at home?"

Declarative:

aiwa,

yes

kadru=yu

live=2S.NOM

i

LOC

ruma'

house

ma-lrinay

ITR-play

"Yes, I played at home."

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| NOM | nominative |

| LOC | locative |

| ITR | intransitive |

Morphology

[edit]Puyuma verbs have four types of focus:[6]: 25–26

- Actor focus: Ø (no mark), -em-, -en- (after labials), me-, meʔ-, ma-

- Object focus: -aw

- Referent focus: -ay

- Instrumental focus: -anay

There are three verbal aspects:[6]: 25–26

- Perfect

- Imperfect

- Future

There are two modes:[6]: 25–26

- Imperative

- Hortative future

Affixes include:[6]: 25–26

- Perfect: Ø (no mark)

- Imperfect: Reduplication; -a-

- Future: Reduplication, sometimes only -a-

- Hortative future: -a-

- Imperative mode: Ø (no mark)

Affixes

[edit]Puyuma uses prefixes, suffixes, infixes, and circumfixes as affixes. There can be more than one affix per word. Further, prefixes are the most common affixes used in Puyuma, followed by suffixes, circumfixes, and then infixes with the least (see list of affixes at the end of this section).

Examples of an infix and circumfix are as follows:

Infix -[4]: 109

tr-em-akaw

AV.steal

dra

ID.OBL

paisu

money

i

SG.NOM

isaw

Isaw

"Isaw stole money."

Circumfix-[4]: 284

ka-salrem-an

period.of.time-to.plant-period.of.time

"the cultivating season"

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| AV | actor voice |

| ID | indefinite |

| OBL | oblique |

| SG | singular |

Affix Types

[edit]Verbalizers are a common type of affixes and the verbalizer affixes can have a variety of functions. Some examples, among many more affixes, are tua- and kitu-. Another type of affix is a nominalizer, like -an, which is also among many other nominalizer affixes.

1. tua-eraw

make-wine

"to make wine"

2. kitu-bangsar

become-handsome

'to become a matured young man'.

3. akan-an

eat-NMZ

"food"[4]: 282–284

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| NMZ | nominalizer |

There are also a number of affixes in Puyuma that can be markers of type of voice. For example, -ay:

tu=trakaw-ay=ku

3.GEN=steal-LV=1S.NOM

"he stole from me"[4]: 110

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 3 | third person |

| GEN | genitive |

| LV | locative voice |

| 1S | first person singular |

The Puyuma affixes are:[4]: 282–285

- Prefixes

- ika-: the shape of; forming; shaping

- ka-: stative marker

- kara-: collective, to do something together

- kare-: the number of times

- ki-: to get something

- kir-: to go against (voluntarily)

- kitu-: to become

- kur-: be exposed to; be together (passively)

- m-, ma-: actor voice affix/intransitive affix

- maka-: along; to face against

- mara-: comparative/superlative marker

- mar(e)-: reciprocal; plurality of relations

- mi-: to have; to use

- mu-: anticausative marker

- mutu-: to become, to transform into

- pa-/p-: causative marker

- pu-: put

- puka-: ordinal numeral marker

- piya-: to face a certain direction

- si-: to pretend to

- tara-: to use (an instrument), to speak (a language)

- tinu-: to simulate

- tua-: to make, to form

- u-: to go

- ya-: to belong to; nominalizer

- Suffixes

- -a: perfective marker; numeral classifier

- -an: nominalizer; collective/plural marker

- -anay: conveyance voice affix/transitive affix

- -aw: patient voice affix/transitive affix

- -ay: locative voice affix/transitive affix

- -i, -u: imperative transitive marker

- Infixes

- -in-: perfective marker

- -em-: actor voice affix/intransitive affix

- Circumfixes

- -in-anan: the members of

- ka- -an: a period of time

- muri- -an: the way one is doing something; the way something was done

- sa- -an: people doing things together

- sa- -enan: people belonging to the same community

- si- -an: nominalizer

- Ca- -an, CVCV- -an: collectivity, plurality

Roots

[edit]In Puyuma, roots can be either bound or free. Most roots can be free in Puyuma.

An example of a bound root is:

ma-trina

"big"

where the root is 'trina' and cannot stand alone.

An example of a free root is:

kiping

"clothes"

where the root is kiping and can stand alone.[4]: 29

Clitics

[edit]Clitics are found in a lot of Puyuma words. A main difference between clitics and affixes in Puyuma is that clitics are not counted in the stress rule for speaking and, in general, do not receive stress. Clitics can occur either at the front of the word (proclitics) or at the end of the word (enclitics).[4]

Proclitics

[edit]Genitive bound pronouns are proclitics and act as either actor verbs or as nouns. An example of an actor agreement marker is tu=:

tu=pa-karun-ay

3.GEN=CAUS-work-LV

(kan

(SG.OBL

senayan)

Senayan)

"She(/Senayan) made them work."

An example of the possessor of a possessed object maker is also tu=:[4]: 30

salraw

very

inaba

good

tu=tranguru'

3.PSR=head

"He is very smart."

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| CAUS | causative |

| PSR | possessor |

Enclitics

[edit]Enclitics are nominative bound pronouns, vocative marker =a, and aspectual markers =la, =driya, and =dar.[4]: 32

Nominative bound pronoun clitics attach to the predicate in positive sentences and to the negator in negative sentences, in most cases. For example, a nominative bound pronoun in a positive sentence is =ku:

s-em-alretrag=ku

AV.pour.out=1S.NOM

dra

ID.OBL

enay

water

"I poured out water."

A nominative bound pronoun in a negative sentence is also =ku, except the pronoun is attached to the negator:[4]: 31–32

adri=ku

NEG=1S.NOM

s-em-alretrag

AV.pour.out

dra

ID.OBL

enay

water

"I didn't pour out water."

The three aspect-marking enclitcs, =la, =driya, and =dar, indicate perfective, imperfective, and frequentative, respectively. They also attach to the predicate or the negator (in negative sentences). For example:[4]: 32

1.

payas=la

right.away=PERF

mar-belrias

PR-turn

"She returned right away."

2.

adri=la

NEG=PERF

makeser

strong

mar-belrias

PR-turn

m-uka

AV-go

i

LOC

uma'

farm

"She was not strong enough to return to the farm."

Last, the vocative marker attaches to a personal noun, i.e. a name or a term for a family member/relative. For example:[4]: 34

ama=a

father=VCT

pulang-i=mi

help-LV:IMP=1P.NOM

"Father, help us."

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| NEG | negator |

| PERF | perfective |

| PR | plurality of relations |

| VCT | vocative |

| IMP | imperative |

| 1P | first person plural |

Reduplication

[edit]In Puyuma, reduplication indicates plural, durative, intensive, iterative, or progressive, and only roots can be reduplicated.[4]: 34

There are various types of reduplication in Puyuma; fossilized reduplication (a stem consists of two identical parts - can be monosyllabic or disyllabic), Ca- reduplication (the first consonant of a syllable followed by -a- is reduplicated and it can occur with another reduplication process), disyllabic reduplication (the last two syllables minus the coda of a stem are reduplicated), first syllable reduplication (the first syllable of a stem is reduplicated), rightward reduplication (the last syllable of a stem is reduplicated), serial reduplication (a reduplicated segment is reduplicated again).[4]: 35, 38, 42, 44–45

Ca- reduplication is a main subtype of reduplication in Puyuma. Different rules are applied to words with different characteristics, for example, in a disyllabic word, the first consonant of the word is followed by -a- and the duo is prefixed to the word, dukur 'to pound', da-dukur 'will pound.' However, in trisyllabic or quadrisyllabic words, the first consonant of the second to last syllable is taken and followed by -a- then inserted right before the second to last syllable, for example, dalrekeng 'wet', da-lra-lrekeng 'will be wet.'[4]: 38

Another example of reduplication is of the disyllabic form, where the last two syllables, without the coda, are reduplicated. For example, ragumul 'fur', ra-gumu-gumul 'fluffy.'[4]: 42

Syntax

[edit]Articles include:[7]: 27

- i – singular personal

- a – singular non-personal

- na – plural (personal and non-personal)

Word Order

[edit]Puyuma is a nominative-accusative case language. Puyuma has a verb-initial word order, as exemplified in the following sentence:[4]: 109

tr-em-akaw

AV.steal

dra

ID.OBL

paisu

money

i

SG.NOM

isaw

Isaw

"Isaw stole money."

References

[edit]- ^ Puyuma at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Teng, Stacy Fang-Ching (2009). Case Syncretism in Puyuma. Languages and Linguistics. Vol. 10.

- ^ "Ethnologue: Languages of the World". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Fang-Ching., Teng, Stacy (2008). A reference grammar of Puyuma, an Austronesian language of Taiwan. Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics. Canberra, A.C.T.: Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University. ISBN 9780858835870. OCLC 271786603.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zeitoun, Elizabeth; Cauquelin, Josiane. "An ethnolinguistic note on the etymology of 'Puyuma'". Language and Linguistics Monograph Series W-5: 653–663.

- ^ a b c d Cauquelin, Josiane. (2004). The aborigines of Taiwan : the Puyuma : from headhunting to the modern world. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0203498593. OCLC 57198062.

- ^ Cauquelin, Josiane. (1991). Dictionnaire puyuma-français. Paris: Ecole française d'Extrême Orient. ISBN 2855395518. OCLC 31979363.