User:CFCF/sandbox/Human body

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2013) |

This user page or section recently underwent a major revision or rewrite and may need further review. You can help Wikipedia by assisting in the revision. If this user page has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. This page was last edited by CommonsDelinker (talk | contribs) 9 months ago. (Update timer) |

| Human body | |

|---|---|

Human body features displayed on bodies on which body hair and male facial hair has been removed | |

| Anatomical terminology |

The human body is the entire structure of a human organism and comprises a head, neck, torso, two arms and two legs. By the time the human reaches adulthood, the body consists of close to 100 trillion cells,[1] the basic unit of life.[2] These cells are organised biologically to eventually form the whole body.

Structure

[edit]Constituents of the human body

In a normal man weighing 60 kg | ||

| Constituent | Weight[3] | Percent of atoms[3] |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen | 6.0 kg | 63% |

| Oxygen | 38.8 kg | 25.5% |

| Carbon | 10.9 kg | 9.5% |

| Nitrogen | 1.9 kg | 1.4% |

| Calcium | 1.2 kg | 2.0% |

| Phosphorus | 0.6 kg | 0.2% |

| Potassium | 0.2 kg | 0.07% |

Size

[edit]The average height of an adult male human (in developed countries) is about 1.7–1.8 m (5'7" to 5'11") tall and the adult female is about 1.6–1.7 m (5'2" to 5'7") tall.[4] Height is largely determined by genes and diet. Body type and composition are influenced by factors such as genetics, diet, and exercise.

Human anatomy

[edit]

Human anatomy (gr. ἀνατομία, "dissection", from ἀνά, "up", and τέμνειν, "cut") is primarily the scientific study of the morphology of the human body.[5] Anatomy is subdivided into gross anatomy and microscopic anatomy.[5] Gross anatomy (also called topographical anatomy, regional anatomy, or anthropotomy) is the study of anatomical structures that can be seen by the naked eye.[5] Microscopic anatomy is the study of minute anatomical structures assisted with microscopes, which includes histology (the study of the organization of tissues),[5] and cytology (the study of cells). Anatomy, human physiology (the study of function), and biochemistry (the study of the chemistry of living structures) are complementary basic medical sciences that are generally together (or in tandem) to students studying medical sciences.

In some of its facets human anatomy is closely related to embryology, comparative anatomy and comparative embryology,[5] through common roots in evolution; for example, much of the human body maintains the ancient segmental pattern that is present in all vertebrates with basic units being repeated, which is particularly obvious in the vertebral column and in the ribcage, and can be traced from very early embryos.

Generally, physicians, dentists, physiotherapists, nurses, paramedics, radiographers, and students of certain biological sciences, learn gross anatomy and microscopic anatomy from anatomical models, skeletons, textbooks, diagrams, photographs, lectures, and tutorials. The study of microscopic anatomy (or histology) can be aided by practical experience examining histological preparations (or slides) under a microscope; and in addition, medical and dental students generally also learn anatomy with practical experience of dissection and inspection of cadavers (dead human bodies). A thorough working knowledge of anatomy is required for all medical doctors, especially surgeons, and doctors working in some diagnostic specialities, such as histopathology and radiology.

Human anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry are basic medical sciences, which are generally taught to medical students in their first year at medical school. Human anatomy can be taught regionally or systemically;[5] that is, respectively, studying anatomy by bodily regions such as the head and chest, or studying by specific systems, such as the nervous or respiratory systems. The major anatomy textbook, Gray's Anatomy, has recently been reorganized from a systems format to a regional format, in line with modern teaching.[6][7]

Human physiology

[edit]Human physiology is the science of the mechanical, physical, bioelectrical, and biochemical functions of humans in good health, their organs, and the cells of which they are composed. Physiology focuses principally at the level of organs and systems. Most aspects of human physiology are closely homologous to corresponding aspects of animal physiology, and animal experimentation has provided much of the foundation of physiological knowledge. Anatomy and physiology are closely related fields of study: anatomy, the study of form, and physiology, the study of function, are intrinsically related and are studied in tandem as part of a medical curriculum.

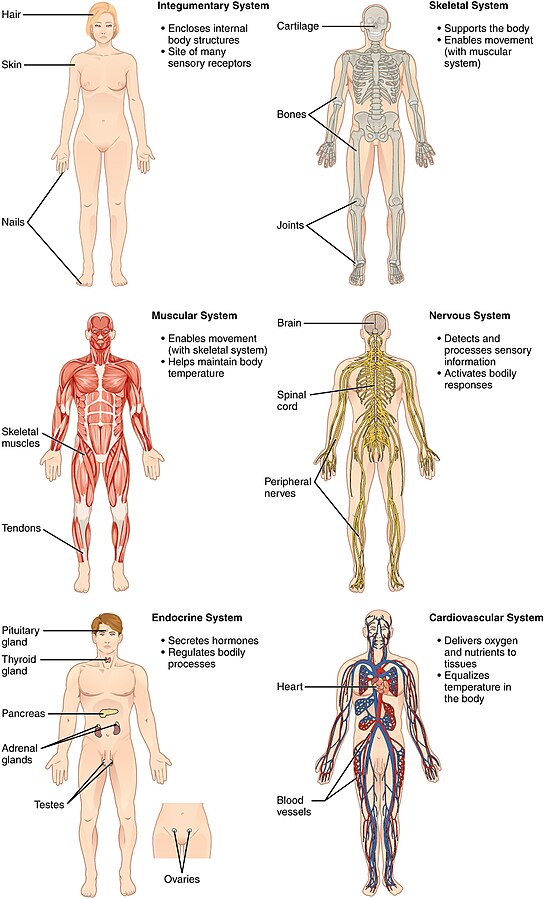

Systems

[edit]Traditionally, the academic discipline of physiology views the body as a collection of interacting systems, each with its own combination of functions and purposes. Each body system contributes to the homeostasis of other systems and of the entire organism. No system of the body works in isolation, and the well-being of the person depends upon the well-being of all the interacting body systems.

| System | Clinical study | Physiology | |

| The nervous system consists of the central nervous system (which is the brain and spinal cord) and peripheral nervous system. The brain is the organ of thought, emotion, memory, and sensory processing, and serves many aspects of communication and control of various other systems and functions. The special senses consist of vision, hearing, taste, and smell. The eyes, ears, tongue, and nose gather information about the body's environment. | neuroscience, neurology (disease), psychiatry (behavioral), ophthalmology (vision), otolaryngology (hearing, taste, smell) | neurophysiology | |

|

The musculoskeletal system consists of the human skeleton (which includes bones, ligaments, tendons, and cartilage) and attached muscles. It gives the body basic structure and the ability for movement. In addition to their structural role, the larger bones in the body contain bone marrow, the site of production of blood cells. Also, all bones are major storage sites for calcium and phosphate. | osteology (skeleton), orthopedics (bone disorders) | cell physiology, musculoskeletal physiology |

| The circulatory system or cardiovascular system comprises the heart and blood vessels (arteries, veins, capillaries). The heart propels the circulation of the blood, which serves as a "transportation system" to transfer oxygen, fuel, nutrients, waste products, immune cells, and signalling molecules (i.e., hormones) from one part of the body to another. The blood consists of fluid that carries cells in the circulation, including some that move from tissue to blood vessels and back, as well as the spleen and bone marrow. | cardiology (heart), hematology (blood) | cardiovascular physiology[8][9] The heart itself is divided into three layers called the endocardium, myocardium and epicardium,(liquidation) which vary in thickness and function.[10] | |

| The respiratory system consists of the nose, nasopharynx, trachea, and lungs. It brings oxygen from the air and excretes carbon dioxide and water back into the air. | pulmonology. | respiratory physiology | |

|

The gastrointestinal system consists of the mouth, esophagus, stomach, gut (small and large intestines), and rectum, as well as the liver, pancreas, gallbladder, and salivary glands. It converts food into small, nutritional, non-toxic molecules for distribution by the circulation to all tissues of the body, and excretes the unused residue. | gastroenterology | gastrointestinal physiology |

|

The integumentary system consists of the covering of the body (the skin), including hair and nails as well as other functionally important structures such as the sweat glands and sebaceous glands. The skin provides containment, structure, and protection for other organs, but it also serves as a major sensory interface with the outside world. | dermatology | cell physiology, skin physiology |

|

The urinary system consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. It removes water from the blood to produce urine, which carries a variety of waste molecules and excess ions and water out of the body. | nephrology (function), urology (structural disease) | renal physiology |

| The reproductive system consists of the gonads and the internal and external sex organs. The reproductive system produces gametes in each sex, a mechanism for their combination, and a nurturing environment for the first 9 months of development of the offspring. | gynecology (women), andrology (men), sexology (behavioral aspects) embryology (developmental aspects) | reproductive physiology | |

|

The immune system consists of the white blood cells, the thymus, lymph nodes and lymph channels, which are also part of the lymphatic system. The immune system provides a mechanism for the body to distinguish its own cells and tissues from alien cells and substances and to neutralize or destroy the latter by using specialized proteins such as antibodies, cytokines, and toll-like receptors, among many others. | immunology | immunology |

|

The main function of the lymphatic system is to extract, transport and metabolize lymph, the fluid found in between cells. The lymphatic system is very similar to the circulatory system in terms of both its structure and its most basic function (to carry a body fluid). | oncology, immunology | oncology, immunology |

|

The endocrine system consists of the principal endocrine glands: the pituitary, thyroid, adrenals, pancreas, parathyroids, and gonads, but nearly all organs and tissues produce specific endocrine hormones as well. The endocrine hormones serve as signals from one body system to another regarding an enormous array of conditions, and resulting in variety of changes of function. There is also the exocrine system. | endocrinology | endocrinology |

Homeostasis

[edit]The term "homeostasis" is the property of a system that regulates its internal environment and tends to maintain a stable, relatively constant condition of properties such as temperature or pH. It can be either an open or closed system. In simple terms, it is a process in which the body's internal environment is kept stable. This is required for the body to function sufficiently. The Homeostatic process is essential for the survival of each cell, tissue, and body system. Maintaining a stable internal environment requires constant monitoring, mostly by the brain and nervous system. The brain receives information from the body and responds appropriately through the release of various substances like neurotransmitters, catecholamines, and hormones. Individual organ physiology furthermore facilitates the maintenance of homeostasis of the whole body e.g. Blood pressure regulation: the release of renin by the kidneys allow blood pressure to be stabilized (Renin, Angiotensinogen, Aldosterone System), though the brain helps regulate blood pressure by the Pituitary releasing Anti-Diuretic Hormone (ADH). Thus, homeostasis is maintained within the body as a whole, dependent upon its parts.

The traditional divisions by system are somewhat arbitrary. Many body parts participate in more than one system, and systems might be organized by function, by embryological origin, or other categorizations. In particular, is the "neuroendocrine system", the complex interactions of the neurological and endocrinological systems which together regulate physiology. Furthermore, many aspects of physiology are not as easily included in the traditional organ system categories.

The study of how physiology is altered in disease is pathophysiology.

Society and culture

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2013) |

Depiction

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2013) |

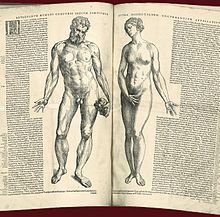

Gross anatomy has become a key part of visual arts. Basic concepts of how muscles and bones function and deform with movement is key to drawing, painting or animating a human figure. Many books such as "Human Anatomy for Artists: The Elements of Form", are written as a guide to drawing the human body anatomically correctly.[11] Leonardo da Vinci sought to improve his art through a better understanding of human anatomy. In the process he advanced both human anatomy and its representation in art.

Because the structure of living organism is complex, anatomy is organized by levels, from the smallest components of cells to the largest organs and their relationship to other organs.

Appearance

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2013) |

History of anatomy

[edit]The history of anatomy has been characterized, over a long period of time, by a continually developing understanding of the functions of organs and structures in the body. Methods have also advanced dramatically, advancing from examination of animals through dissection of fresh and preserved cadavers (dead human bodies) to technologically complex techniques developed in the 20th century.

History of physiology

[edit]The study of human physiology dates back to at least 420 B.C. and the time of Hippocrates, the father of medicine.[12] The critical thinking of Aristotle and his emphasis on the relationship between structure and function marked the beginning of physiology in Ancient Greece, while Claudius Galenus (c. 126-199 A.D.), known as Galen, was the first to use experiments to probe the function of the body. Galen was the founder of experimental physiology.[13] The medical world moved on from Galenism only with the appearance of Andreas Vesalius and William Harvey.[14]

During the Middle Ages, the ancient Greek and Indian medical traditions were further developed by Muslim physicians. Notable work in this period was done by Avicenna (980-1037), author of the The Canon of Medicine, and Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288), among others.[citation needed]

Following from the Middle Ages, the Renaissance brought an increase of physiological research in the Western world that triggered the modern study of anatomy and physiology. Andreas Vesalius was an author of one of the most influential books on human anatomy, De humani corporis fabrica.[15] Vesalius is often referred to as the founder of modern human anatomy.[16] Anatomist William Harvey described the circulatory system in the 17th century,[17] demonstrating the fruitful combination of close observations and careful experiments to learn about the functions of the body, which was fundamental to the development of experimental physiology. Herman Boerhaave is sometimes referred to as a father of physiology due to his exemplary teaching in Leiden and textbook Institutiones medicae (1708).[citation needed]

In the 18th century, important works in this field were by Pierre Cabanis, a French doctor and physiologist.[citation needed]

In the 19th century, physiological knowledge began to accumulate at a rapid rate, in particular with the 1838 appearance of the Cell theory of Matthias Schleiden and Theodor Schwann. It radically stated that organisms are made up of units called cells. Claude Bernard's (1813–1878) further discoveries ultimately led to his concept of milieu interieur (internal environment), which would later be taken up and championed as "homeostasis" by American physiologist Walter Cannon (1871–1945).[clarification needed]

In the 20th century, biologists also became interested in how organisms other than human beings function, eventually spawning the fields of comparative physiology and ecophysiology.[18] Major figures in these fields include Knut Schmidt-Nielsen and George Bartholomew. Most recently, evolutionary physiology has become a distinct subdiscipline.[19]

The biological basis of the study of physiology, integration refers to the overlap of many functions of the systems of the human body, as well as its accompanied form. It is achieved through communication that occurs in a variety of ways, both electrical and chemical.

In terms of the human body, the endocrine and nervous systems play major roles in the reception and transmission of signals that integrate function. Homeostasis is a major aspect with regard to the interactions within an organism, humans included.

See also

[edit]- Outline of human anatomy

- Body image

- Body schema

- Human development

- Comparative physiology

- Comparative anatomy

Further reading

[edit]- Raincoast Books (2004). Encyclopedic Atlas Human Body. Raincoast Books. ISBN 978-1-55192-747-3.

- Daniel D. Chiras (1 June 2012). Human Body Systems: Structure, Function, and Environment. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4496-4793-3.

- Adolf Faller; Michael Schünke; Gabriele Schünke (2004). The Human Body: An Introduction to Structure and Function. Thieme. ISBN 978-1-58890-122-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Richard Walker (30 March 2009). Human Body. Dk Pub. ISBN 978-0-7566-4545-8.

- DK Publishing (18 June 2012). Human Body: A Visual Encyclopedia. ISBN 978-1-4654-0143-4.

- DK Publishing (30 August 2010). The Complete Human Body: The Definitive Visual Guide. ISBN 978-0-7566-7509-7.

- Saddleback (1 January 2008). Human Body. Saddleback Educational Publ. ISBN 978-1-59905-234-2.

- Babsky, Evgeni (1989). Evgeni Babsky (ed.). Human Physiology, in 2 vols. Translated by Ludmila Aksenova; translation edited by H. C. Creighton (M.A., Oxon). Moscow: Mir Publishers. ISBN 5-03-000776-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Sherwood, Lauralee (2010). Human Physiology from cells to systems (7 ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/cole. ISBN 978-0-495-39184-5.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help)

References

[edit]External links

[edit]- Human Physiology textbook at Wikibooks

- (in English and Arabic) The Book of Humans from the early 18th century

- Referencing site and detailed pictures showing information on the human body anatomy and structure

- ^ Page 21 Inside the human body: using scientific and exponential notation. Author: Greg Roza. Edition: Illustrated. Publisher: The Rosen Publishing Group, 2007. ISBN 1-4042-3362-8, ISBN 978-1-4042-3362-1. Length: 32pages

- ^ Cell Movements and the Shaping of the Vertebrate Body in Chapter 21 of Molecular Biology of the Cell fourth edition, edited by Bruce Alberts (2002) published by Garland Science.

The Alberts text discusses how the "cellular building blocks" move to shape developing embryos. It is also common to describe small molecules such as amino acids as "molecular building blocks". - ^ a b Page 3 in Chemical storylines. Author: George Burton. Edition 2, illustrated. Publisher: Heinemann, 2000. ISBN 0-435-63119-5, ISBN 978-0-435-63119-2. Length: 312 pages

- ^ http://www.human-body.org/ (dead link)

- ^ a b c d e f "Introduction page, "Anatomy of the Human Body". Henry Gray. 20th edition. 1918". Retrieved 27 March 2007.

- ^ "Publisher's page for Gray's Anatomy. 39th edition (UK). 2004. ISBN 0-443-07168-3". Archived from the original on 20 February 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2007.

- ^ "Publisher's page for Gray's Anatomy. 39th edition (US). 2004. ISBN 0-443-07168-3". Archived from the original on 9 February 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2007.

- ^ "Cardiovascular System". U.S. National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) [dead link] - ^ Human Biology and Health. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. 1993. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- ^ "The Cardiovascular System". SUNY Downstate Medical Center. 2008-03-08. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Goldfinger, Eliot (1991). Human Anatomy for Artists: The Elements of Form. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505206-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Physiology - History of physiology, Branches of physiology". www.Scienceclarified.com. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ^ Fell, C.; Griffith Pearson, F. (2007). "Thoracic Surgery Clinics: Historical Perspectives of Thoracic Anatomy". Thorac Surg Clin. 17 (4): 443–8, v. doi:10.1016/j.thorsurg.2006.12.001.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Galen". Discoveriesinmedicine.com. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ^ "Page through a virtual copy of Vesalius's De Humanis Corporis Fabrica". Archive.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ^ "Andreas Vesalius (1514-1567)". Ingentaconnect.com. 1999-05-01. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (2004). "Soul Made Flesh: The Discovery of the Brain - and How It Changed the World". J Clin Invest. 114 (5): 604–604. doi:10.1172/JCI22882.

- ^ Feder, Martin E. (1987). New directions in ecological physiology. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-34938-3.

- ^ Garland, Jr, Theodore; Carter, P. A. (1994). "Evolutionary physiology" (PDF). Annual Review of Physiology. 56 (56): 579–621. doi:10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.003051. PMID 8010752.