User:Buggs1613/sandbox

- This page discusses a philosophical view on free will. See other uses of the term Compatibility.

Compatibilism is the belief that free will and determinism are compatible ideas, and that it is possible to believe in both without being logically inconsistent.[1] Compatibilists believe freedom can be present or absent in situations for reasons that have nothing to do with metaphysics.[2] They define free will as freedom to act according to one's motives without arbitrary hindrance from other individuals or institutions.[citation needed]

For example, courts of law make judgments, without bringing in metaphysics, about whether an individual was acting of their own free will in specific circumstances. It is assumed in a court of law that someone could have done otherwise than they did—otherwise no crime would have been committed.

Similarly, political liberty is a non-metaphysical concept.[3] Statements of political liberty, such as the United States Bill of Rights, assume moral liberty, i.e. the ability to choose to do otherwise than one does.

History

[edit]Compatibilism was championed by the ancient stoics[4] and medieval scholastics (such as Thomas Aquinas),[5] and by Enlightenment philosophers (like David Hume and Thomas Hobbes).[6] More specifically, the scholastics, including Thomas Aquinas, rejected what would now be called "incompatibilism"—they held that humans could do otherwise than they do, otherwise the concept of sin is meaningless. As for the Jesuits, their concern was to reconcile the claim of God's foreknowledge of who would be saved with moral agency. The term "compatibilism" itself was coined as late as the 20th century.

During the 20th century, compatibilists presented novel arguments that differed from the classical arguments of Hume, Hobbes, and John Stuart Mill.[7] Importantly, Harry Frankfurt popularized what are now known as Frankfurt counterexamples to argue against incompatibilism,[8] and developed a positive account of compatibilist free will based on higher-order volitions.[9] Other "new compatibilists" include Gary Watson, Susan R. Wolf, P. F. Strawson, and R. Jay Wallace.[10]

Contemporary compatibilists range from the philosopher and cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett, particularly in his works Elbow Room (1984) and Freedom Evolves (2003), to the existentialist philosopher Frithjof Bergmann. Perhaps the most renowned contemporary defender of compatibilism is John Martin Fischer.

Defining free will

[edit]

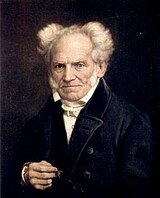

Compatibilists often define an instance of "free will" as one in which the agent had freedom to act according to their own motivation. That is, the agent was not coerced or restrained. Arthur Schopenhauer famously said "Man can do what he wills but he cannot will what he wills."[11]

In other words, although an agent may often be free to act according to a motive, the nature of that motive is determined. Also note that this definition of free will does not rely on the truth or falsity of causal determinism.[2] This view also makes free will close to autonomy, the ability to live according to one's own rules, as opposed to being submitted to external domination.

Alternatives as imaginary

[edit]

Some compatibilists will hold both Causal Determinism (all effects have causes) and Logical Determinism (the future is already determined) to be true. Thus statements about the future (e.g., "it will rain tomorrow") are either true or false when spoken today. This compatibilist free will should not be understood as some kind of ability to have actually chosen differently in an identical situation. A compatibilist can believe that a person can choose between many choices, but the choice is always determined by external factors.[12] If the compatibilist says "I may visit tomorrow, or I may not", he is saying he does not know what he will choose—if he will choose to follow the subconscious urge to go or not.

Criticisms

[edit]

Critics of compatibilism often focus on the definition(s) of free will: incompatibilists may agree that the compatibilists are showing something to be compatible with determinism, but they think that something ought not to be called "free will". Incompatibilists might accept the "freedom to act" as a necessary criterion for free will, but doubt that it is sufficient. Basically, they demand more of "free will". The incompatibilists believe free will refers to genuine (e.g., absolute, ultimate) alternate possibilities for beliefs, desires, or actions, rather than merely counterfactual ones.

Compatibilists are sometimes called "soft determinists" pejoratively (William James' term). James accused them of creating a "quagmire of evasion" by stealing the name of freedom to mask their underlying determinism.[13] Immanuel Kant called it a "wretched subterfuge" and "word jugglery".[14] Kant's argument turns on the view that, while all empirical phenomena must result from determining causes, human thought introduces something seemingly not found elsewhere in nature—the ability to conceive of the world in terms of how it ought to be, or how it might otherwise be. For Kant, subjective reasoning is necessarily distinct from how the world is empirically. Because of its capacity to distinguish is from ought, reasoning can 'spontaneously' originate new events without being itself determined by what already exists.[15] It is on this basis that Kant argues against a version of compatibilism in which, for instance, the actions of the criminal are comprehended as a blend of determining forces and free choice, which Kant regards as misusing the word "free". Kant proposes that taking the compatibilist view involves denying the distinctly subjective capacity to re-think an intended course of action in terms of what ought to happen.[14] Ted Honderich explains his view that the mistake of compatibilism is to assert that nothing changes as a consequence of determinism, when clearly we have lost the life-hope of origination.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Coates, D. Justin; McKenna, Michael (February 25, 2015). "Compatibilism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ^ a b Podgorski, Daniel (October 16, 2015). "Free Will Twice Defined: On the Linguistic Conflict of Compatibilism and Incompatibilism". The Gemsbok. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ Locke, John (1690). The Second Treatise of Civil Government.

- ^ Ricardo Salles, "Compatibilism: Stoic and modern." Archiv für Geschichte der Philosophie 83.1 (2001): 1-23.

- ^ As long as determinism is here understood as the principle that "nothing happens without a cause". Cf. e.g. Summa contra gentiles, the part about Providence, c. 88-91. See also Free will#Free will as a psychological state. In times of the Counter-Reformation views which were close to compatibilism were held openly by at least two Catholic orders: the Jesuits (molinism) and the Dominicans.

- ^ Michael McKenna: Compatibilism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edward N. Zalta (ed.). 2009.

- ^ Kane, Robert (2005). A Contemporary Introduction to Free Will. Oxford University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-19-514970-8.

- ^ Kane 2005, p. 83

- ^ Kane 2005, p. 94

- ^ Kane 2005, pp. 98, 101, 107, 109.

- ^ Schopenhauer, Arthur (1945). "On the Freedom of the Will". The Philosophy of American History : The Historical Field Theory. Translated by Morris Zucker. p. 531.

- ^ Harry G. Frankfurt (1969). "Alternate Possibilities and Moral Responsibility," Journal of Philosophy 66 (3):829-39.

- ^ James, William. 1884 "The Dilemma of Determinism," Unitarian Review, September, 1884. Reprinted in The Will to Believe, Dover, 1956, p.149

- ^ a b Kant, Immanuel 1788 (1952).The Critique of Practical Reason, in Great Books of the Western World, vol. 42, Kant, Univ. of Chicago, p. 332

- ^ Kant, Immanuel 1781 (1949).The Critique of Pure Reason, trans. Max Mueller, p. 448

- ^ Ted Honderich, The Consequences of Determinism, 1988, p.169