User:Brigade Piron/sandbox10

Background

[edit]French North Africa and the Vichy regime

[edit]

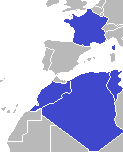

In contrast to French West Africa and French Equatorial Africa which were federations of colonies and existed administrative entities in their own right, French North Africa was never more than a term of convenience to refer to the three separately governed territories under different forms of colonial regime.

- Vichy Regime and seizure of power by Philippe Pétain

- General Maxime Weygand appointed Vichy's Delegate-General in North Africa in September 1940

- 162,000 Jews living in North Africa in 1936.[1]

- Political importance of North AFrica for Vichy and denial of territory to Germans in Armistice of 22 June 1940

- Pétainist sympathies are generally stronger in the French colonial empire than in mainland France because of the lack of direct experience of Vichy policies and the realities of the German occupation.[2]

- The historian Richard Vinen describes Algeria and the rest of French North Africa as "probably the most Pétainist area in all of the French Empire". He attributed this to the fact that "Algeria never saw German soldiers and the European population there found it easy to believe that Vichy would combine conservative reform with preparation for a military revenge against Germany." At the same time, "[s]ome Muslim notables were sympathetic to Pétain, either because they found his emphasis on authority and patriotism to be appealing, or because they believed that Vichy might grant them political concessions".[2]

- Algerians had not experienced war first-hand.[3]

- French settler population is "not a naturally right-wing population" in view of its relative poverty, urbanisation, and high proportion of people of Spanish, Maltese, and Italian ancestry. During the interwar period, many had "moved to the right under the influence of anti-Semitism, oppositon to Algerian nationalism and sympathy, on the part of Spaniards, for Franco's cause during the Spanish Civil War".[3]

- "Weygand's particular brand of Pétainism, patriotic, military and, at least implicitly, anti-German - was particularly suited to Algeria."[3] Although the metropolitan army remained small, Weygand was permitted to raise a much larger army 120,000-strong in North Africa under the terms of the Franco-German armistice.[3]

- Some Muslims are appointed to Vichy's National Council (Conseil national).[3]

Algeria

[edit]Algeria was invaded by France in 1830 and had a unique legal status as a de jure part of metropolitan France after 1848. Aside from the native population, a large population of white settlers lived in Algeria numbering _____ by 1940. Settlers were particularly concentrated along the coast and, in particular, in the major urban centres of Algiers, Oran, Bône (modern-day Annaba), Constantine, and Sidi Bel Abbès.

- Crémieux Decree of 1870

- 111,021 Jews with French citizenship in 1941 and 6,625 Jews of another nationality[1]

Morocco and Tunisia

[edit]Tunisia and Morocco became protectorates in 1881 and 1912 respectively in which their existing monarchs (beys) retained notional independence under French tutelage.

- 59,485 native Jews in Tunisia in 1936 with a further 20,000 Jews from France or Italy.[1]

Vichy rule, 1940–1942

[edit]Algeria

[edit]

After consolidating its position, the Vichy regime introduced a package of discriminatory antisemitic legislation after October 1940 affecting Jews in France which was then extended to other parts of the French colonial empire, including French North Africa as France's only colonial territories with significant Jewish minorities. There was widespread support for restrictive legislation among French settlers in North Africa.[4]

The first antisemitic legislation to be published was a law abrogating the Crémieux Decree on 7 October 1940 whose effect was limited to Algeria.[5][6] At a stroke, Algerian Jews were deprived of their historic status as citizens and established the new legal status of "Israelite Native of Algeria" (Israélite indigène d'Algérie) governed by the Indigénat in the same way as the Muslim majority. The new status was in fact more restrictive as it denied rights available to Muslim Algerians who had been able to apply individually for citizenship since 1919.[7]

Although enacted before the abrogation of the Crémieux Decree, the First Law on the Status of Jews introduced on 3 October 1940 was only made public shortly afterwards and also affected Algeria.[5] It defined Jewish status and prohibited Jews from serving in local government, the civil service, and Armistice Army. 70 percent of Jewish public employees in Algeria had been sacked by the end of 1940 and 80 percent by Autumn 1941.[8]

Vichy introduced the Second Law on the Status of Jews on 2 June 1941 which was intended to marginalise Jews within the national economy and, in particular, limited the ability of Jews to work in the liberal professions such as law or medicine. It was extended to Algeria by a decree of 20 October 1941.[9] A numerus clausus was established which saw many Algerian Jews thrown out of their longstanding professions. A decree of 21 November 1941 provided the Governor-General of Algeria with the power to seize Jewish-owned property in order to "eliminate all Jewish influence over the national economy".[10]

Jews were limited to 3 percent of places at public institutes of higher education which was particularly popular among French settlers.[10] Georges Hardy, rector of the Academy of Algiers, successfully lobbied to have the numerus clausus extended to public primary and secondary education and Jewish students were banned from sitting particular exams.[10] Educational discrimination was profoundly upsetting to Algerian Jews who did not possess private confessional schools of their own, unlike in Tunisia and Morocco, and who had seen the French public education system as an important part of their integration into Republican values.[11]

Maurice Eisenbeth, Grand Rabbi of Algeria, protested against the measures but without any success. Algeria's Jewish community also established its own assistance programmes for the families of civil servants removed from their jobs. After the measures affecting education, it set up a network of schools for excluded Jewish students which numbered 70 primary schools and 5 secondary schools by late 1942.[12] Contrary to his own wishes, Eisenbeth was ordered to serve as head of the Judenrat-style General Union of Israelites in Algeria (Union générale des israélites d'Algérie) established on 14 February 1942 as a counterpart to the General Union of Israelites in France (Union générale des israélites de France) but this had not become active by the time of the Allied landings.[13]

Tunisia and Morocco

[edit]- General Charles Noguès, Resident-General in Morocco, was keen to avoid outbursts of anti-Jewish sentiment in order to avoid inflaming indigenous anti-semitism which might threaten the colonial order.[14] After the Battle of France, a number of anti-Jewish riots and murders did take place at El Kef, El Ksour, Siliana in Tunisia in August 1940 sparked by particular concerns about the economic situation.[15]

- French settlers in Tunisia and Morocco supported legislation.[4]

- A serious antisemitic riot took place at Gabès (Tunisia) in May 1941.[15]

The first law on the status of Jews was introduced with minor differences to Morocco as a Dahir of 31 October 1940 and in Tunisia by a Vizirial decree of 30 November 1940.[16] The legislation applied slightly different definitions of Jewish status in Morocco on the basis of religious adhesion among "natives" and on a racial basis for Europeans.[17] Although providing slightly more discretion about retaining Jewish civil servants and soldiers in certain posts, 435 Jews had been thrown out of civil service positions in Morocco by early 1941.[9]

Given the distinctive status of Tunisia and Morocco, the enactment of antisemitic legislation was more ambiguous than in Algeria. Admiral Jean-Pierre Esteva, Resident-General in Tunisia, was also concerned about the harmful effect of strict implementation of antisemitic legislation on the internal economic and social situation in Tunisia and sought to pursue a "weak policy" on the issue in dealings with the Bey.[18] Both Noguès and Esteva successfully prevented the appointment of local delegates from Xavier Vallat's Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs which they saw as an attempt to limit their prerogatives.[14]

Although not directly opposing the enactment of the legislation, the Beys of Tunisia and Morocco also remained suspicious of the antisemitic legislation as an interference in their prerogatives.[19] The Tunisian regent decorated 20 Jews with the prestigious Order of Glory in 1942 in order to show that Tunisian Jews remained his subjects rather than those of the French.[14]

Among the later economic measures, there were also minor differences in Tunisia and Morocco which adapted the legislation to local imperatives, such as banning the longstanding practice of Jews living in the European Quarters of Morroccan cities.[10]

Relations between Jews and Muslims

[edit]Nazi Germany and Italy sought to exploit Islamic antisemitism through radio broadcasts in Arabic inciting violence against Jews. Although this propaganda enjoyed some success in the Middle East, it had little effect on North Africa.[20] The historian Norman Stillman writes that "the great majority of Muslims in North Africa remained relatively impassive in relation to Vichy's anti-Jewish policy".[20]

- Some receptiveness in early months owing to historic tensions - violence - Gabes pogrom (May 1941)

- Cautious response of Tunisian and Moroccan monarchs

- Others were sympathetic

North African labour and internment camps

[edit]North Africa was used extensively by the Vichy regime to hold "undesirables" (indésirables) from mainland France in a network of internment and labour camps scattered across predominantly desert regions of Algeria and Morocco.[a] As well as foreign former soldiers demobilised from the French Foreign Legion, these included political prisoners (politiques) such as "[anticolonial] nationalists, communists and trade unionists, Spanish republicans, German and Austrian anti-Nazis, [and] Brigadists". A significant proportion of these were Jewish although Jews were only indirectly targetted.[21] Although mortality rates were relatively high among the prisoners, Vichy policy was intended to "exclude and humiliate, not to exterminate".[22]

Various forms of labour units were established including the Groups of Foreign Workers (Groupements de travailleurs étrangers, GTE), Autonomous Groups of Foreign Workers (Groupements de Travailleurs Étrangers Autonomes, GTEA), and Groups of Demobilised Foreign Workers (Groupements de Travailleurs Démobilisés, GTD) under the auspices of the Ministry of Industrial Production and Labour.[b] Many were sent to the Sahara desert to work on the Algerian section of the Mediterranean–Niger Railway intended to connect the Mediterranean coast with Dakar in French West Africa. Others were used as labour in coal mines. Workers performed strenuous manual labour and lived in poor conditions in nearby isolated camps. As the historian Lévisse-Touzé describes, "[t]hey were subjected to inhuman conditions, suffering humiliation, even abuse at the slightest lapse. Badly dressed, badly clothed, badly fed, wearing espadrilles on hot sands infested with scorpions and vipers, they received pay of 50 centimes a day. They were guarded day and night by soldiers."[23]

Jews were significantly overrepresented among both the demobilised legionnaires and political prisoners held in the camps in North Africa.[24] Most were refugees or recent immigrants of Central or Eastern European origin. According to one estimate, there were 2,000 to 3,000 Jews among the 15,000 to 20,000 prisoners held by 1942 in Algeria.[citation needed][c] Algerian Jews demobilised from the Armistice Army were, however, specifically grouped into separate Groups of Israelite Workers (Groupements de travailleurs israélites, GTI) based at Bedeau near Sidi Bel Abbès.[24]

Allied landings and the German occupation of Tunisia, 1942–43

[edit]Allied landings and the restoration of French rule

[edit]

As part of the North African campaign, the Allies launched a series of naval landings on 8 November 1942 in three regions of Morocco and Algeria. The landings, involving predominantly American ground units, were codenamed Operation Torch and anticipated little resistance in capturing their primary targets of Casablanca, Oran, and Algiers. As part of a deal to ensure their surrender, the Allies reached a agreement with Admiral François Darlan, Vichy's leading representative in the region, on 16 November 1942 which effectively preserved much of the pre-existing regime in North Africa and has been described as "Vichyism under an American protectorate".[25]

The agreement with Darlan was very controversial among the other Allied powers. Harold Macmillan, a British diplomat and Minister-Resident for the Mediterranean, noted that "in spite of repeated promises, the political prisoners remained interned, Jews persecuted, and collaborationists in place" in North Africa.[26] After Darlan's assassination by a French royalist on 24 December 1942, General Henri Giraud emerged as the leading figure rather than the Free French General Charles de Gaulle who were distrusted by the American government. Giraud was a conservative nationalist and was also sympathetic to many aspects of the Vichy regime[3] and held antisemitic views. Macmillan claimed Giraud had told him that Allied criticism of Vichy was due to the fact that Jews "owned so many of our newspapers".[26] Vinen observes that the agreement with Darlan "confirmed the view in Algeria that there was no sharp divide between being pro-Vichy and anti-German".[3] Despite their mutual enmity, Giraud and de Gaulle ultimately agreed to form the French Committee of National Liberation (Comité français de Libération nationale, CFLN) at Algiers in June 1943 and de Gaulle ultimately emerged as its sole leading figure in November 1943.

Ahead of the landings, the Allies had reached an agreement with resistance groups to co-ordinate the seizure of power in Algiers. Jews were significantly overrepresented within resistance networks and, amongst others, had formed the Géo Gras Group, originally a local sports club, which had transitioned from a community self-defence group into a full resistance group affiliated with the Free French.[27] 377 resistance members ultimately assisted with the successful seizure of key locations in Algiers on the night of 7 November 1942 of whom 315 were Jews.[28] Among the leaders in the putsch was José Aboulker who came from an eminent Algerian Jewish family. Jewish resistance members were particularly victimised under the Darlan and Giraud regimes, and 12 leading members were arrested after the assassination of Darlan. José Aboulker eventually travelled to London where he received a senior position in the Free French.[29]

Contrary to expectations, the Allied landings did not immediately see the repeal of Vichy's restrictions on Jews in North Africa. Girard issued an ordonnance on 14 March 1943 to restore the Republican legislative system but expressly retained Vichy's suppression of the Crémiaux Decree.[30] The American diplomat Robert Daniel Murphy considered that Giraud's position was sensible because to reverse the abrogation might "infuriate" the Muslim majority amid fears about Arab nationalism.[31] The abrogation was only expressly repealed by the CFLN on 20 October 1943.[30]

German-occupied Tunisia

[edit]

After the landings in Morocco and Algeria, the Allies launched an unsuccessful overland "run for Tunis" in an attempt to secure Tunisia before it could be occupied by German and Italian forces from Sicily and Libya. The attempt failed and it was only after protracted fighting that German forces were only finally forced to evacuate at the end of the Tunisia campaign in May 1943. As a result, Tunisia remained under German occupation for more than seven months.

After the first German forces landed in Tunisia, the leaders of the Jewish community including its president Moïse Borgel were arrested on 23 November 1942.[22] Borgel was ordered by the kommandantur at Tunis to choose Jews to undertake forced labour. Appeals to Esteva and French authorities led to official protests.[22] Nonetheless, forced labour was officially instituted on 6 December 1942 and ultimately applied to 5,000 Tunisian Jews who were often held in poor conditions.[22]

Aside from forced labour, the German authorities made a demand for 20 million francs from the Jews of Tunisia on 21 December 1942 as notional reparations for the Anglo-American bombing of Tunisian cities.[30] Separately, Germans often extorted money from individual Jews and local Jewish communities, including at Sfax.[30]

North African Jews in France, 1942–44

[edit]Jews of North African origin who lived in mainland France before the war, notably in Marseilles, were caught up in the Holocaust in France.[32] As persecution escalated, Jews began to be rounded up and deported to concentration and extermination camps in Eastern Europe after March 1942. 76,000 Jews were ultimately deported from France of whom the vast majority were killed. Among them, the activist Serge Klarsfeld estimated that 1,500 Jews of Algerian origin were deported to Eastern Europe.[32] A detailed study by the historian Jean Laloum in 1988 put the number at 1,111 of whom only 53 (4.7%) survived the war.[33]

Aftermath

[edit]

- At time of Arab-Israeli War, 1948 Anti-Jewish riots in Oujda and Jerada in which 44 Jews were killed. Aftermath sees 18,000 Moroccan Jews leave for Israel in 1948-49. Large-scale emigration intensified during the years prior to Morocco's independence in 1956

- Moroccan and Tunisian Jews return to ambiguous pre-war status and are particularly influenced by post-war Zionism. Many emigrate to Israel after Israeli War of Independence.

- Algeria saw mass emigration of Jews during the Algerian War with most of those remaining leaving ahead of Algerian indepdnence in 1962 with the exodus of Pieds-Noirs. Algerian nationality code of 1963 denied citizenship to non-Muslims.

Tunisian Jews employed as forced labourers by the German authorities were granted the status of Holocaust survivors in Israel in 2022 entitling them to additional social benefits.[34]

- 4,000 Tunisian Jews (25% of total population) emigrated illegally to Mandatory Palestine between 1943 and 1948.[35]

Beginning in 2018, the German non-governmental organisation PixelHELPER sought to build a Holocaust memorial and educational centre at Ait Faska near Marrakesh in Morocco publicised as "North Africa’s first-ever Holocaust memorial". Only a week after the annoucement, the still-unfinished construction was demolished by Moroccan authorities on the grounds that no authorisation had been provided by the Ministry of Culture.[36][37]

See also

[edit]- The Holocaust in Libya - an Italian colonial territory.

- Spain and the Holocaust

- Turkey and the Holocaust

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Zytnicki 2004, p. 155.

- ^ a b Vinen 2006, p. 90.

- ^ a b c d e f g Vinen 2006, p. 91.

- ^ a b Zytnicki 2004, p. 161.

- ^ a b Cantier 2002, p. 72.

- ^ Zytnicki 2004, p. 156.

- ^ Cantier 2002, p. 73.

- ^ Cantier 2002, p. 75.

- ^ a b Zytnicki 2004, p. 158.

- ^ a b c d Zytnicki 2004, p. 159.

- ^ Zytnicki 2004, p. 160.

- ^ Zytnicki 2004, p. 164.

- ^ Zytnicki 2004, p. 165.

- ^ a b c Zytnicki 2004, p. 162.

- ^ a b Zytnicki 2004, p. 167.

- ^ Zytnicki 2004, p. 157.

- ^ Zytnicki 2004, pp. 157–8.

- ^ Zytnicki 2004, pp. 160–2.

- ^ Stillman 2016, p. 71.

- ^ a b Stillman 2016, p. 68.

- ^ Lévisse-Touzé 2004, p. 180.

- ^ a b c d Zytnicki 2004, p. 169.

- ^ Lévisse-Touzé 2004, pp. 183–4.

- ^ a b c Zytnicki 2004, p. 168.

- ^ Neiberg 2021, p. 198.

- ^ a b Neiberg 2021, p. 217.

- ^ Laskier 1994, p. 82.

- ^ Laskier 1994, p. 82-3.

- ^ Stillman 2016, pp. 64–5.

- ^ a b c d Zytnicki 2004, p. 170.

- ^ Neiberg 2021, pp. 197–8.

- ^ a b Laloum 1988, p. 33.

- ^ Laloum 1988, p. 34.

- ^ Forsher, Efrat (12 August 2022). "Hundreds of Tunisian Jews get Holocaust survivor status due to late testimony". Israel Hayom. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Ben Achour, Olfa (2017). "L'émigration des Juifs de Tunisie en Palestine dans les années 1940. L'impact de l'idéal sioniste". Archives Juives. 50 (2): 127–147.

- ^ Chernik, Ilanit (27 August 2019). "Moroccan Authorities demolish Holocaust, LGBTQ+ memorial near Marrakesh". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ Chernik, Ilanit (22 August 2019). "North Africa's first-ever Holocaust memorial is in the works". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Laloum, Jean (1988). "La déportation des Juifs natifs d'Algérie". Le Monde Juif (129): 33–48.

- Cantier, Jacques (2002). L'Algérie sous le régime de Vichy. Paris: Odile Jacob. ISBN 2-7381-1057-6.

- Zytnicki, Colette (2004). "La politique antisémite du régime de Vichy dans les colonies". In Cantier, Jacques; Jennings, Éric (eds.). L'Empire colonial sous Vichy. Paris: Odile Jacob. pp. 153–176. ISBN 978-2-7381-8395-8.

- Lévisse-Touzé, Christine (2004). "Les camps d'internement d'Afrique du Nord. Politiques répressives et populations". In Cantier, Jacques; Jennings, Éric (eds.). L'Empire colonial sous Vichy. Paris: Odile Jacob. pp. 177–194. ISBN 978-2-7381-8395-8.

- Laskier, Michael M. (1994). North African Jewry in the Twentieth Century: The Jews of Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-5072-9.

- Neiberg, Michael S. (2021). When France Fell: The Vichy Crisis and the Fate of the Anglo-American Alliance. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674270114.

- Vinen, Richard (2006). The Unfree French: Life under the Occupation. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-713-99496-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Gershon, Yitzhak (2016). "Les Juifs de Tunisie sous le régime de Vichy et sous l'occupation allemande, octobre 1940-mai 1943. L'attitude des autorités et de l'environnement". Revue de l'histoire de la Shoah (205): 263-296.

- Kenbib, Mohammed (2014). "Moroccan Jews and the Vichy Regime, 1940–42". Journal of North African Studies. 19 (4): 540–553. doi:10.1080/13629387.2014.950523.

- Aouate, Yves C. (2016). "Les Algériens musulmans et les mesures antijuives du gouvernement de Vichy". Revue d'histoire de la Shoah (205): 413-446.

- Boum, Aomar; Stein, Sarah Abrevaya, eds. (2019). The Holocaust and North Africa. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9781503607057.

- Peterson, Terrence (2015). "The 'Jewish Question' and the 'Italian Peril': Vichy, Italy, and the Jews of Tunisia, 1940–2". Journal of Contemporary History. 50 (2): 234–258. doi:10.1177/0022009414542537. JSTOR 43697373.

- Friedl, Sophie (2016). "Negotiating and Compromising. Jewish Leaders' Scope of Action in Tunis During Nazi Rule (November 1942–May 1943)". In Bajohr, Frank; Löw, Andrea (eds.). The Holocaust and European Societies: Social Processes and Social Dynamics. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 225–240. ISBN 978-1-349-84899-7.

- Laskier, Michael M. (1991). "Between Vichy Antisemitism and German Harassment: The Jews of North Africa during the Early 1940s". Modern Judaism. 11 (3): 343–369. ISSN 0276-1114. JSTOR 1396112.

- Abitbol, Michel (1989). The Jews of North Africa during the Second World War. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814318249.

- Slyomovics, Susan (2012). "French Restitution, German Compensation: Algerian Jews and Vichy's Financial Legacy". Journal of North African Studies. 17 (5): 881–901. doi:10.1080/13629387.2012.723434.

External links

[edit]

Central and Eastern Europe

[edit]- Era of Appeasement: annexation (Anschluss) of Austria (12 March 1938) and Munich Agreement (30 September 1938) and subsequent dismantling and invasion of Czechoslovakia (14–15 March 1939)

- Ostensibly to protect German minorities in Eastern Europe

- Nazi-Soviet Pact (23 August 1939)

- Joint German-Soviet invasion of Poland (1 September 1939)

- France and the United Kingdom declared war against Germany in September 1939 at the start of the so-called Phoney War.

Nordic states

[edit]- Norway and Denmark as neutral countries and their planned invasion

- German invasion of Denmark (9 April 1940) and its rapid surrender

- German invasion of Norway

Western Europe

[edit]- German invasion of France begins on 10 May 1940 and was carried out by invading neutral Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg which were rapidly defeated.

- Difference between Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands and King Leopold III of the Belgians.

- French Army and the British Expeditionary Force rapidly defeated and British withdrawal at Dunkirk. French Army pushed southwards and Italian invasion of France (10 June 1940).

- Philippe Pétain came to power, Armistice of 22 June 1940, and series of authoritarian reforms in France.

- Capture of more than a million Belgian and French prisoners of war most of whom were deported to camps in Germany and Eastern Europe for political leverage and for use as labour in the German war effort.

- Widespread belief in Western Europe that conflict would end in a negotiated peace in 1940.

South-East Europe

[edit]Administration and governance

[edit]Annexation

[edit]- "Heim ins Reich" and Volksdeutsche

- Outright annexation of German-speaking French Alsace and Lorraine and Belgian Eupen-Malmedy

- Annexation of Luxembourg in 1942

- Meant its inhabitants were subject to conscription into the German Army and other programmes run within Nazi Germany itself

Occupation

[edit]- Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907

- Distinction between civil and military government. Inter-agency rivalry between Wehrmacht, SS, and Nazi Party.

Puppet states

[edit]Allies and neutrals

[edit]- Francoist Spain (Spain during World War II): Meeting at Hendaye (23 Oct 1940) and subsequent economic relationship and Blue Division (1941–44)

- Sweden (Sweden during World War II) and Switzerland (Switzerland during the World Wars)

- Italian participation in the Eastern Front

- Romanian, Slovak, and Croatian armies

- Bulgarian refusal to contribute troops to the Eastern Front

European states and regions

[edit]Pre-war European states occupied or otherwise wholly or partly under the control of Nazi Germany and its Allies after the start of German territorial expansion in 1938:

Austria

Austria Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Albania

Albania Poland

Poland Danzig

Danzig Denmark

Denmark Norway

Norway Luxembourg

Luxembourg Netherlands

Netherlands Belgium

Belgium Italy

Italy France

France United Kingdom (Channel Islands)

United Kingdom (Channel Islands)

Bulgaria

Bulgaria Estonia

Estonia Finland

Finland Greece

Greece Hungary

Hungary Latvia

Latvia Lithuania

Lithuania Monaco

Monaco Romania

Romania San Marino

San Marino Soviet Union (Ukraine, Byelorussia and parts of Russia)

Soviet Union (Ukraine, Byelorussia and parts of Russia) Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia

Policy, propaganda and collaboration

[edit]Accommodation

[edit]- Committee of Secretaries-General and Galopin doctrine (Belgium)

- Local police and civil servants

- Christian religious authorities

- Political parties - example of Dutch Union (Nederlandse Unie) established to keep the NSB out of power by co-operating with German demands

Collaboration and collaborationism

[edit]- Historical distinction between pragmatic collaboration by political and economic elites (collaboration) and the ideologically motivated kind (collaborationism).

- Mainstream collaboration by authoritarian but non-Nazi elites in Vichy France, Denmark, Greece

- Radical Nazi and pro-German factions in France, Belgium, etc. which see German rule as basis for local revival

- Germanic SS

- Foreign volunteers in the Wermacht and Waffen-SS

"European" and anti-communist propaganda

[edit]Economic extraction

[edit]- Greater Economic Space (Großraumwirtschaft)

- occupation costs

- labour deportation

- expropriation

- Organisation Todt

- severe rationing

- Prolonged famine in Greece (1941–44) and in the Netherlands (1944–45)

Civil resistance

[edit]- Underground media in German-occupied Europe

- V-for-Victory campaign

- BBC European Service, Radio Londres, Radio Oranje, Radio Belgique etc

- Strikes: Strike of the 100,000 (Belgium, May 1941); February strike (Netherlands, Feb 1941), Luxembourg anti-conscription strike (September 1942), Milk strike (September 1941)

- Maquis and partisans

Genocide, mass-murder and persecution

[edit]The Holocaust

[edit]- Anti-Semitism always part of Nazi ideology and Hitler had given a speech in January 1939 in which he made a "prophecy" that the "Jewry" would be exterminated if war broke out. Historians are divided about the point at which a policy of genocidal killing was adopted and whether the initiative came from the higher echelons of the Nazi regime or regional officials attempting to carry out what they perceived as Hitler's intention.

- Early persecution measures - discriminatory laws, ghettoisation, and initial intention to deport European Jews to Eastern Europe.

- Increasing radicalisation after invasion of Soviet Union. Intensification of mass-killings.

- Yellow badge

Other racial persecution

[edit]Political repression

[edit]- Geheime Feldpolizei and "Gestapo", actually Sicherheitspolizei (SIPO) and Sicherheitsdienst (SD)

- Communism, Freemasonry, some clerics from the Catholic and Protestant churches etc.

Collapse

[edit]Military difficulties

[edit]- Allied bombing

- Redeployment of German units to fronts

- Increasingly assertive resistance

- Increasing reliance on local paramilities and violent reprisals

Armed resistance

[edit]- Soviet partisans, Jewish partisans, Maquis, Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (April–May 1943), Warsaw Uprising (August–October 1944)

- SOE, SIS, OSS etc.

Allied breakthroughs in East and West

[edit]- Operation Bagration (June–August 1944)

- Dutch famine of 1944–1945

Legacy

[edit]References

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- General studies

- Cesarani, David (2017). Final Solution: The Fate of the Jews 1933–1949. London: Pan Books. ISBN 9780330535373.

- Klemann, Hein A.M.; Kudryashov, Sergei (2012). Occupied Economies: An Economic History of Nazi-occupied Europe, 1939-1945. London: Berg. ISBN 978-1-84520-823-3.

- Mazower, Mark (2008). Hitler's Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-713-99681-4.

- Müller, Rolf-Dieter (2012). The Unknown Eastern Front: The Wehrmacht and Hitler's Foreign Soldiers. New York: I.B. Taurus. ISBN 978-1-78076-072-8.

- Scherner, Jonas; White, Eugene N., eds. (2016). Paying for Hitler's War: The Consequences of Nazi Hegemony for Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107279131.

- Stahel, David, ed. (2018). Joining Hitler's Crusade: European Nations and the Invasion of the Soviet Union, 1941. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-51034-6.

- Country or regional studies

- Bunting, Madeleine (2004). The Model Occupation: The Channel Islands under German Rule, 1940-1945. London: Pimlico. ISBN 1-8441-3086-X.

- Dallin, Alexander (1981). German Rule in Russia, 1941-1945: A Study of Occupation Policies (2nd ed.). Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 0-86531-102-1.

- Hirschfeld, Gerhard (1988). Nazi Rule and Dutch Collaboration: The Netherlands under German Occupation, 1940-1945. London: Berg. ISBN 9780854961467.

- Jackson, Julian (2003). France: The Dark Years, 1940-1944. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925457-6.

- Laub, Thomas J. (2009). After the Fall: German Policy in Occupied France, 1940-1944. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199539321.

- Mazower, Mark (2001). Inside Hitler's Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941-44. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06552-3.

- Stratigakos, Despina (2020). Hitler's Northern Utopia: Building the New Order in Occupied Norway. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691198217.

Bibliography

[edit]-

Danish policemen participate in the arrest of Communist activists in June 1941

--->

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).