User:Bloodofox/Thor rewrite

In Germanic mythology, Thor (from Old Norse Þōrr) is a hammer-wielding god associated with thunder, lightning, storms, oak trees, strength, destruction, fertility, healing, death, and the protection of mankind.

Ultimately stemming from Proto-Indo-European religion, Thor is a prominently mentioned god throughout the recorded history of the Germanic peoples, from the Roman occupation of regions of Germania, to the tribal expansions of the Migration Period, to his extreme popularity during the Viking Age, where, in the face of the process of the Christianization of Scandinavia, large amounts of personal names bearing his name give testimony to his high position among the Norse pagans, and emblems of his hammer, Mjöllnir, were worn in defiance. After the Christianization of Scandinavia and into the modern period, Thor continued to be acknowledged in rural folklore throughout Germanic regions. Thor is frequently referenced in place names, the day of the week Thursday ("Thor's day") bears his name, and names stemming from the pagan period containing his name continue to be used today.

In Norse mythology, largely recorded in Iceland from traditional material stemming from Scandinavia, numerous tales and information about Thor is provided. In these sources, Thor bears at least fourteen names, is the husband of the golden-haired goddess Sif, is the lover of the jötunn Járnsaxa, and is described as fierce-eyed, red-haired and red-bearded. With Sif, Thor fathered the goddess (and possible valkyrie) Þrúðr; with Járnsaxa, he fathered Magni; with a mother whose name is not recorded, he fathered Móði, and is the stepfather of the god Ullr. The same sources list Thor as the son of the god Odin and Fjörgyn, the personified earth, and by way of Odin, Thor has numerous brothers. Thor has two servants, Þjálfi and Röskva, rides in a chariot led by two goats, Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr (that he eats and resurrects), is ascribed three dwellings (Bilskirnir, Þrúðheimr, and Þrúðvangr), and he wields the mountain-crushing hammer, Mjöllnir, wears the belt Megingjörð, the iron gloves Járngreipr, and owns the staff Gríðarvölr. Thor's exploits, including his slaughter of his foes, and his fierce battle with the monstrous serpent Jörmungandr—and their foretold mutual deaths during the events of Ragnarök—are recorded throughout sources for Norse mythology.

Etymology and eponyms

[edit]

The name Thor, which re-entered English by way of Old Norse Þōrr, and, like all cognates, ultimately derives from Proto-Germanic *þunraR, meaning "thunder". The Old English form of the god's name is Thunor, and, like Old Norse Þōrr and Þunorr, is cognate to Old High German Donar.[1]

Thor is the namesake of the weekday name Thursday. By employing a practice known as interpretatio germanica at around 1 AD, the Germanic peoples adopted the Roman weekly calender, and replaced the names of Roman gods with their own, and so Latin dies Iovi ("day of Jupiter") was converted into Proto-Germanic *Þonares dag ("Thor's day"), from which stems modern English "Thursday" and all other Germanic weekday cognates.[2]

Beginning in the Viking Age, personal names containing the theonym Thor are recorded with great frequency. Prior to the Viking Age, no know examples are recorded. Thor-based names may have flourished during the Viking Age as a defiant response to attempts at Christianization, similar to the widescale Viking Age practice of wearing Thor's hammer pendants.[3]

Numerous place names in Scandinavia and, to a lesser extent, England contain the Old Norse Thor. The identification of these place names as pointing to religious significance is complicated by the aforementioned common usage of Thor as a personal name element. Cultic significance may only be assured in place names containing the elements -vé (signifying the location of a vé, a type of pagan Germanic shrine), -hof (a structure used for religious purposes, see heathen hofs), and -lundr (a holy grove). The place name Thorslundr is recorded with particular frequency in Denmark (and has direct cognates in Norse settlements in Ireland, such as Coill Tomair), whereas Thorshof appears particularly often in southern Norway.[3]

In England, names based off of the native Old English form, Thunor (in contrast with the Old Norse form of the name, later introduced by the Norsemen), place names based off of Thunores hlæw (directly cognate to the above mentioned Old Norse Thorslundr) are recorded, as is the place name Thurstable (Old English "Thunor's pillar"). In what is now Germany, locations named after Thor are sparsely recorded, but an amount of locations called Donnersberg (German "Donner's mountain") may derive their name from the deity Donner, the southern Germanic form of the god's name.[3]

In 19th century Iceland, a specific breed of fox was known as holtaþórr("Thor of the holt"), likely due to it's red coat.[4]

Attestations

[edit]From Tacitus to the Viking Age

[edit]

The earliest records of the Germanic peoples were recorded by the Romans, and in these works Thor is frequently referred to—via a process known as interpretatio romana (where characteristics perceived to be similar by Romans result in identification of a non-Roman god as a Roman deity)—as either the Roman god Jupiter (also known as Jove) or the Greco-Roman demigod Hercules. The first clear example of this occurs in the Roman historian Tacitus's 1 AD work Germania, where, writing about the religion of the Germanic peoples, he comments that "among the gods Mercury is the one they principally worship. They regard it as a religious duty to offer to him, on fixed days, human as well as other sacrificial victims. Hercules and Mars they appease by animal offerings of the permitted kind". In this instance, Tacitus refers to the god Odin as "Mercury", Thor as "Hercules", and the god Tyr as "Mars". In Thor's case, this is likely due to similarities between Thor's hammer and Hercules's club. In his Annals, Tacitus again refers to the veneration of "Hercules" by the Germanic peoples; he records a wood beyond the river Weser (in what is now northwestern Germany) as dedicated to him.[5]

In Germanic areas occupied by the Roman Empire, coins and votive objects dating from the 2nd and 3rd century AD have been found with Latin inscriptions referring to "Hercules", and so in reality, with varying levels of likelihood, referring to Thor by way of interpetatio romana.[6]

The first recorded instance of the name of the god appears in the post-Roman period, where a piece of jewelry (a fibula), the Nordendorf fibula, dating from the 7th century AD and found in Bavaria, bears an Elder Futhark inscription that contains the name "Donar", the southern Germanic form of the god's name.[7]

According to Vita Bonifatii auctore Willibaldo, in the 8th century, the Christian missionary Boniface miraculously felled an oak tree dedicated to "Jove" (Thor's Oak) around Hesse, Germany.[8] Around the second half of the 8th century, Old English tales of a figure named "Thunor"—the Old English form of Thor's name—are recorded, a figure who likely refers to an Old English cult of the god. In relation, Thunor is sometimes used in Old English texts to gloss Jupiter, the god may be referenced in the poem Solomon and Saturn, and the Old English expression þunnorad ("thunder ride") may refer to the god's thunderous, goat-led chariot.[9] A 9th century AD codex from Mainz, Germany, known as the Old Saxon Baptismal Vow records the name of three Old Saxon gods; UUôden (Old Saxon "Wodan"), Saxnôte, and Thunaer (Old Saxon "Thor") for use in Christianizing Germanic pagans by way of renouncing their native gods as demons.[10]

In the 11th century, chronicler Adam of Bremen records in his Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum that a statue of Thor, who Adam describes as "mightiest", sits in the Temple at Uppsala in the center of a triple throne (flanked by Woden and "Fricco") located in Gamla Uppsala, Sweden. Adam details that "Thor, they reckon, rules the sky; he governs thunder and lightning, winds and storms, fine weather and fertility" and that "Thor, with his mace, looks like Jupiter". Adam details that the people of Uppsala had appointed priests to each of the gods, and that the priests were to offer up sacrifices. In Thor's case, he continues, these sacrifices were done when plague or famine threatened.[11] Earlier in the same work, Adam relays that in 1030 an English preacher by the name of Wulfred was lynched by assembled Germanic pagans for "profaning" a representation of Thor.[12]

Two objects with runic inscriptions invoking Thor date from the 11th century, one from England and one from Sweden. The first, the Canterbury Charm from Canterbury, England, calls upon Thor to heal a wound by banishing a thurs.[13] The second, the Kvinneby amulet, invokes protection by both Thor and his hammer.[14]

Post-Viking Age

[edit]In the 12th century, centuries after Norway was "officially" Christianized, Thor was still being invoked by the population, as evidenced by a stick bearing a runic message found among the Bryggen inscriptions in Bergen, Norway. On the stick, both Thor and Odin are called upon for help; Thor is asked to "receive" the reader, and Odin to "own" them.[15] Also around the 12th century, iconography of the Christianizing 11th century king Olaf II of Norway absorbed elements of the native Thor; Olaf II had become a familiarly red-bearded, hammer-wielding figure.[16]

The Eddas, Heimskringla, and sagas

[edit]In the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from traditional source material reaching into the pagan period, Thor appears (or is mentioned) in the poems Völuspá, Grímnismál, Skírnismál, Hárbarðsljóð, Hymiskviða, Lokasenna, Þrymskviða, Völundarkviða, and Alvíssmál.[17]

In the poem Völuspá, a dead völva recounts the history of the universe and foretells the future to the disguised god Odin, including the death of Thor. Thor, she foretells, will due battle with the great serpent during the immense mythical war waged at Ragnarök, and there he will slay the monstrous snake, yet he will only be able to take nine steps after before succumbing to the venom of the beast:

|

Benjamin Thorpe translation:

|

Henry Adams Bellows translation:

|

After, says the völva, the sky will turn black before fire engulfs the world, the stars will disappear, flames will dance before the sky, steam will rise, the world will be covered in water, and then it will be raise again; green and fertile (see Prose Edda section below for the survival of the sons of Thor, who return after these events with Thor's hammer).[20]

In the poem Grímnismál, the god Odin, in disguise as Grímnir, and tortured, starved and thirsty, imparts in the young Agnar cosmological lore, including that Thor resides in Þrúðheimr, and that, every day, Thor wades through the rivers Körmt and Örmt, and "the two Kerlauger". There, Grímnir says, Thor sits as judge at the immense cosmological world tree, Yggdrasil.[21]

In Skírnismál, the god Freyr's messenger, Skírnir, threatens the fair Gerðr, who Freyr is smitten with, with numerous threats and curses, including that Thor, Freyr, and Odin will be angry with her, and that she risks their "potent wrath".[22]

Thor is the main character of Hárbarðsljóð, where, after traveling "from the east", Thor encounters a ferryman at an inlet by the name of Hárbarðr (Odin, again in disguise), who attempts to hail a ride from. The ferryman, shouting from the inlet, is immediately rude and obnoxious to Thor and refuses to ferry him. At first, Thor holds his tongue, but Hárbarðr only becomes more aggressive, and the poem soon becomes a flyting match between Thor and Hárbarðr, all the while revealing lore about the two, including Thor's killing of several jötnar in "the east" and berzerk women on Hlesey (now the Danish island of Læsø). In the end, Thor ends up walking instead.[23]

Thor again stars in the poem Hymiskviða, where, after the gods invite themselves over to Ægir's home, Thor and the god Týr seek a cauldron large enough for the jötunn Ægir to brew ale for the gods in. The two go to Týr's, where Tyr is disgusted by his nine-hundred-headed grandmother, but his gold-clad mother welcomes them with a horn and, after Hymir—who is not happy to see Thor—comes in from the cold outdoors, helps them find a properly strong cauldron. Thor eats a big meal of two oxen (all the rest eat but one), and then goes to sleep. In the morning, he awakes and informs Hymir that the three of them will go fishing the following evening, and that he will catch plenty of food for the three, but that he needs bait. Hymir tells him to go get some bait from his pasture, which he expects should not be a problem for Thor. Thor goes out into the woods, finds a swart ox, and rips the head off of it.[24]

After a lacuna in the manuscript of the poem,Hymiskviða abruptly picks up again with Thor and Hymir in a boat, out at sea. Hymir catches a few whales at once, and Thor baits his line with the head of the ox. Thor casts his line and the monstrous serpent Jörmungandr bites. Thor pulls serpent on board, and violently slams him in the head with his hammer. Jörmungandr shrieks, and a noisy commotion is heard from underwater before another lacuna appears in the manuscript.[25]

After the second lacuna, Hymir is sitting in the boat, unhappy and totally silent, as they row back to shore. On shore, Hymir suggests that Thor should help him carry a whale back to his farm. Thor picks both the boat and the whales up, and carries it all back to Hymir's farm. After smashing a crystal goblet on Hymir's head, Thor and Tyr are given the cauldron. Tyr can't lift it, but Thor manages to roll it, and so with it they leave. Some distance from Hymir's home, an army led by Hymir of many-headed beings attacks the two, but are killed by the hammer of Thor. And although he finds his goats to be lame in the leg, the two manage to bring the cauldron back, have plenty of ale, and so, from then on, return to Ægir's for more every winter.[26]

In the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, Thor is mentioned in all four books; Prologue, Gylfaginning, and Háttatal.

In Heimskringla, composed in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson, Thor is mentioned in Ynglinga saga, Hákonar saga Góða, Ólafs saga Tryggvason, and Ólafs saga Helga.

Gesta Danorum

[edit]19th century folk beliefs

[edit]Tales about Thor, or influenced by native traditions regarding Thor, continued into the modern period, particularly in Scandinavia. Writing in the 19th century, scholar Jacob Grimm records various phrases surviving into Germanic languages that refer to the god, such as Norwegian Thorsvarme ("Thor's warmth") for lightning, and the Swedish godgubben åfar ("The good old (fellow) is taking a ride" when it thunders. Grimm comments that, at times, Scandinavians often "no longer liked to utter the god's real name, or they wished to extol his fatherly goodness [...]."[27]

Thor remained pictured as a red-bearded figure, as evidenced by the Danish rhyme that yet referred to him as Thor med sit lange skæg ("Thor with the long beard") and the Frisian curse diis ruadhiiret donner regiir! ("let red-haired thunder see to that!").[27]

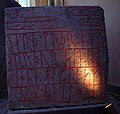

Archaeological record

[edit]On four (or possibly five) runestones, an invocation to Thor appears that reads "May Thor hallow (these runes/this monument)!". The invocation appears thrice in Denmark (DR 110, DR 209, and DR 220), and a single time in Västergötland (Vg 150), Sweden. A fifth appearance may possibly occur on a runestone found in Södermanland, Sweden (Sö 140), but the reading is contested. Pictorial representations of Thor's hammer also appear on a total of five runestones found in Denmark, Västergötland, and Södermanland.[28]

Three stones depict Thor fishing for the serpent Jörmungandr; the Hørdum stone stone in Thy, Denmark, the Altuna Runestone in Altuna, Sweden, one of the Ardre image stones (stone VII) from Gotland, Sweden, and the Gosforth Cross in Gosforth, England.

-

The Sønder Kirkeby Runestone (DR 220), a runestone from Denmark bearing the "May Thor hallow these runes!" inscription

-

A runestone from Södermanland, Sweden bearing a depiction of Thor's hammer

-

The Altuna stone, one of four stones depicting Thor's fishing trip

-

The Gosforth depiction, one of four stones depicting Thor's fishing trip

Pendants in a distinctive shape representing the hammer of Thor (known in Norse sources as Mjöllnir) have frequently been unearthed in Viking Age Scandinavian burials. The hammers were worn as a symbol of Germanic pagan faith and as a symbol of opposition to Christianization; a response to crosses worn by Christians. Casting moulds have been found for the production of both Thor's hammers and Christian crucifixes, and at least one example of a combined crucifixes and hammer has been discovered.[29] The Eyrarland Statue, a copper alloy figure from Eyrarland, Iceland dating from around the 11th century, may depict Thor seated and gripping his hammer.[30]

-

Drawing of a silver-gilted Thor's hammer found in Scania, Sweden

-

Drawing of a 4.6 cm gold-plated silver Mjöllnir pendant found at Bredsätra on Öland, Sweden

Theories and interpretation

[edit]Modern influence

[edit]

In modern times, Thor continues to be referenced in popular culture.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Simek (2007:332).

- ^ Simek (2007:333).

- ^ a b c Simek (2007:321).

- ^ Grimm (1882:177).

- ^ Birley (1999:42 and 106—107).

- ^ Simek (2007:140—142).

- ^ Simek (2007:235—236).

- ^ Simek (2007:238) and Robinson (1916:63).

- ^ See North (1998:238—241) for þunnorad and tales regarding Thunor, see Encyclopedia Britannica (1910:608) regarding usage of Thunor as an Old English gloss for Jupiter (and, for that matter, Tiw employed as a gloss for Mars.

- ^ Simek (2007:276).

- ^ Orchard (1997:168—169).

- ^ North (1998:236).

- ^ McLeod, Mees (2006:120).

- ^ McLeod, Mees (2006:28).

- ^ McLeod, Mees (2006:30

- ^ Dumézil (1973:125).

- ^ Larrington (1999:320).

- ^ Thorpe (1907:7).

- ^ Bellows (1923:23).

- ^ Larrington (1999:11—12).

- ^ Larrington (1999:57).

- ^ Larrington (1999:66).

- ^ Larrington (1999:69-75).

- ^ Larrington (1999:78—80).

- ^ Larrington (1999:81).

- ^ Larrington (1999:82—83).

- ^ a b Grimm (1882:166—177).

- ^ Sawyer (2003:128).

- ^ Simek (2007:219) and Orchard (1997:114).

- ^ Orchard (1997:161).

References

[edit]- Bellows, Henry Adams (1923). The Poetic Edda. American-Scandinavian Foundation

- Chrisholm, Hugh (Editor) (1910). Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 9. The Encyclopædia Britannica Co.

- Dumézil, Georges (1973). Gods of the Ancient Northmen. University of California Press. ISBN 0520020448

- Grimm, Jacob (James Steven Stallybrass Trans.) (1882). Teutonic Mythology: Translated from the Fourth Edition with Notes and Appendix by James Stallybrass, volume I. London: George Bell and Sons.

- MacLeod, Mindy; Mees, Bernard (2006). Runic Amulets and Magic Objects. Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-205-4

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-34520-2

- Robinson, George W. (Trans.) (1916). The Life of Saint Boniface by Willibald. Harvard University Press.

- Sawyer, Birgit (2003). The Viking-Age Rune-Stones: Custom and Commemoration in Early Medieval Scandinavia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199262217

- Simek, Rudolf (2007) translated by Angela Hall. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-513-1

- Thorpe, Benjamin (Trans.) (1907). The Elder Edda of Saemund Sigfusson. Norrœna Society.