User:Basemetal/sandbox

https://ibb.co/dM4ehH

https://ibb.co/bVzqpx

Zeroth Section

[edit]https://web.archive.org/web/20130608203203/http://www.virtusens.de/walther/n_komp_e.htm

http://www.nietzsche.ru/english/music.php3

Umwertung aller Werte (? C.I.D.)

Found a book by Robin Norwood and one by Orlando Figes in the staircase... What. The. Fuck.

lg(ratio) = Log2(ratio) = Log10(ratio)/Log10(2)

cents = 1200 × lg(ratio) and ratio = 2^(cents/1200)

Baroque pitch: 415 Hz. (Thats why all those people on YouTube are flat! I shouldnta left them nasty comments.)

אֹ אׁ אׂ וֹ וׁ וׂ

https://archive.org/stream/modestmussorgsky00calv#page/8/mode/2up

Pillars etc.

[edit]Test: Basemetal

Unity of Action in The Tempest

[edit]In this edit you requested a citation for Shakespeare's adherence to the three unities, particularly the unity of action, in The Tempest.

This is discussed in several Cliff's notes and similar introductory editions of the play, but in the interest of higher quality sourcing I've now cited it to the Arden 3rd edition (Vaughan & Vaughan, 1999, pp. 14–17).

I hope this addresses your concern. Otherwise, a note on the article's talk page might be a good way to gain the input of more of the editors with an interest in Shakespeare topics.

Ah, and just now I notice that in this edit you also requested clarification for the sentence "In Italy in 1600, Giordano Bruno was burnt at the stake for his occult studies."

The example comes, as best I recall, from the source used when writing that section (I thought that was Vaughan and Vaughan as above, but I see it's now cited to other editions). If you can suggest better examples to use that would be very helpful, and particularly if they can be easily cited to a high quality source (the standard is pretty high for the Shakespeare articles since there is such a glut to choose from for most things). The point there is to illustrate contemporary views of magic, so using Bruno as an example is simply because that what our source happened to use (again, as best I recall; it's been a while).

PS. Sorry for the back and forth. I've been working through a WikiProject cleanup listing, so I've touched a hundred other articles since the entries for your citation needed tag above and this clarification needed tag.

Regarding "broken triplets"

[edit]I remember I had that old conversation with you, and I also discovered this final nail in the coffin of the assimilation theory. You will understand that the main argument of that theory was that the notation ![]() 3

3 ![]() was not yet known in Schubert's time, and so he wrote

was not yet known in Schubert's time, and so he wrote ![]() .

. ![]() instead. That this is nonsense can easily be seen from the presence of the former notation as early as Mozart's Don Giovanni (look in the Commendatore scene).

instead. That this is nonsense can easily be seen from the presence of the former notation as early as Mozart's Don Giovanni (look in the Commendatore scene).

Here you go: User talk:Double sharp/Archive 8#Piccolos in E-flat and F.

Half-note appoggiaturas

[edit][1] (scores:Zephyr, with thy downy wing (Callcott, John Wall)) appears to confirm Don Byrd's conjecture: "C.P.E. Bach's Versuch uber die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen (1762?; English translation as: Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments) gives examples of half- and even whole-note appoggiaturas, and it seems very likely that halfs (at least) have been written in real music, but I don't know of an example."

- (I still haven't found the elusive G-sharp major key signature yet, but this partially makes up for it! :-D)

- Didn't you say it was in A World Requiem? Do you have access to the score? Have you checked it? Don will be glad to have his conjecture confirmed. Incidentally didn't you happen to notice a WP user "Don A. Byrd" (in red, that is without a user page)? About a year ago I think I saw such a user contribute to articles having to do with one Kurzweil contraption or another (and I think Don had worked at Kurzweil). But since then I have not been able to find those contributions again. They have vanished. I don't know what happened to them. It might be that I'm simply not able to recall the right article. But besides the username has also disappeared apparently. I tried all the combinations but there's no longer a user of that name at WP. Is there a way to have one's user "account" deleted from WP? If yes, what happens to the contributions attached to that username? Contact Basemetal here 14:35, 7 November 2014 (UTC)

- Cool: I'll write on his talk page. I also found another half-note appoggiatura in the Quoniam from Mozart's C minor Mass.

- His last WP edit was about two weeks ago. If you want the good news to reach him faster and in case he doesn't check WP that often maybe you'd wanna also send him a WP email to let him know. I'm sure you know how to do that but just in case: go to his talk page, look for the "Email this user" link in the left column and click it. Yet another way is to email him directly from your email account. You should be able to find his email at his site. Contact Basemetal here 15:07, 9 November 2014 (UTC)

- Actually he replied rather quickly. ;-)

How do I delete a page in my user space?

[edit]Can I personally delete a page in my user space or do I have to ask an admin? For example I'd like to delete some subpages of my sandbox. In particular this page. But I'd like to know about how this works in general too. Thanks. (If you answer please ping me @Basemetal:). Thanks. Contact Basemetal here 23:44, 10 February 2014 (UTC)

- Basemetal - you can't delete page in your user space (otherwise vandals could move articles into their userspace then delete them, which would cause all sorts of problems), but if you put {{db-user}} on them then an admin will delete them for you. I've deleted the one you linked here. Hope this helps.

- @Basemetal:: Only admins can delete pages. If you want a userspace page deleted (as long as you are the only significant contributor to the page), put the {{db-self}} template on the page, and an admin will come along and delete it.

- I put the templates at the top of two pages I wanted and they're still there. How long does this usually take? The pages are User:Basemetal/Size and duration information for musical works (proposal) and User:Basemetal/sandbox/Varg. Contact Basemetal here 16:47, 12 February 2014 (UTC)

Done Gone now. You actually followed directions too well. {{tl}} is a template used to provide a link to anotehr template (it means "template link") so {{tl|db-user}} is a way of referring to Template: db-user. to actually USE the template, just put it name between pairs of braces, like {{db-user}}.

Done Gone now. You actually followed directions too well. {{tl}} is a template used to provide a link to anotehr template (it means "template link") so {{tl|db-user}} is a way of referring to Template: db-user. to actually USE the template, just put it name between pairs of braces, like {{db-user}}.

- I put the templates at the top of two pages I wanted and they're still there. How long does this usually take? The pages are User:Basemetal/Size and duration information for musical works (proposal) and User:Basemetal/sandbox/Varg. Contact Basemetal here 16:47, 12 February 2014 (UTC)

Double sharps and double flats in key signatures

[edit]Look! Page 53! (And on the next pages it covers the triple-sharp and triple-flat signs! They recommend the ![]() sign, following Alkan's usage instead of Reger's (

sign, following Alkan's usage instead of Reger's (![]() ♯), although strangely their musical example uses Reger's

♯), although strangely their musical example uses Reger's ![]() ♯ in spite of this recommendation. The triple-flat is of course

♯ in spite of this recommendation. The triple-flat is of course ![]() . Double sharp (talk) 21:29, 26 June 2015 (UTC)

. Double sharp (talk) 21:29, 26 June 2015 (UTC)

- Yeah. Page 53 and page 55 are not consistent. Note in a score the triple sharp is placed before (to the left of) the note so the ♯

sign makes more sense (after all you raise things half-step by half-step), but in a text they are placed after (to the right of) the note name so

sign makes more sense (after all you raise things half-step by half-step), but in a text they are placed after (to the right of) the note name so  ♯ make more sense (for the same reason). I'm not saying that explains their quirk. It's just an aside of mine. Contact Basemetal here 22:04, 26 June 2015 (UTC)

♯ make more sense (for the same reason). I'm not saying that explains their quirk. It's just an aside of mine. Contact Basemetal here 22:04, 26 June 2015 (UTC) - Also we still have no example of a "real" use of double accidentals in a signature in a "real" score. Don't know if a table in a harmony textbook counts the same way. Their use of ♯♯ and ♭♭ instead of

and

and  is kind of a comical pedantry. Contact Basemetal here 12:01, 27 June 2015 (UTC)

is kind of a comical pedantry. Contact Basemetal here 12:01, 27 June 2015 (UTC) - Is it true you can't do triple accidentals in LilyPond? Contact Basemetal here 12:01, 27 June 2015 (UTC)

- You cannot enter triple sharps or flats directly, with "fisisis" or "beseses" or similar. What I've done in the above score is to feed LilyPond the notes A, B, C, D, tell it that the key is D

major, and ask it to transpose it down a doubly augmented second to C. This should produce G

major, and ask it to transpose it down a doubly augmented second to C. This should produce G , A

, A , B

, B , C

, C ; but you'll see that it actually produces the enharmonic equvialent A♭ instead of B

; but you'll see that it actually produces the enharmonic equvialent A♭ instead of B .

.

- Similarly, here I've given it the same notes but told it that the key was F

major, and asked for a transposition to C. The second note should be F

major, and asked for a transposition to C. The second note should be F , but LilyPond generates the enharmonic G♯.

, but LilyPond generates the enharmonic G♯.

What's this?

[edit]On 2014/02/10:

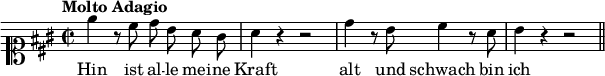

PS. Here, I am talking about certain music conservatories in Europe and Asia which ask prospective composition major students to pass very difficult harmony and/or counterpoint examinations. Here are two examples from “UNDERGRADUTATE” entrance examination for Tokyo University of Arts (Tokyo, Japan).

[Two sample problems from an undergraduate entrance examination for the Tokyo University of the Arts; probably two basses données]

Do not worry if you have no idea to solve these examples. I can assure you that 99% of composition-major students in the US, both undergraduate and graduate will not be able to solve these examples, and the schools will not teach harmony to this level most likely.

Next day changed to:

PS. Here, I am talking about certain music conservatories in Europe and Asia which ask prospective composition major students to pass very difficult harmony and/or counterpoint examinations. Here are two examples from “UNDERGRADUTATE” entrance examination for Tokyo University of Arts (Tokyo, Japan).

[Two sample problems from an undergraduate entrance examination for the Tokyo University of the Arts; probably two basses données]

Do not be discouraged if you have no idea to solve these examples. Many composition-major students around the world, both undergraduate and graduate will find these examples difficult to solve (or maybe impossible). Having the skills to solve these problems is great, however it is not the prerequisite for composition.

Diplomacy?

Stuff

[edit]where is the length of the string, is the tension of the string and is the mass per unit of length (linear density) of the string whose linear density is assumed to be homogeneous.

where is the diameter of the membrane, is the tension on the membrane and is the mass per unit of surface (superficial density) of the membrane whose superficial density is assumed to be homogeneous.

So in the case of the one dimensional string the frequency should be proportional to

In the case of the two dimensional membrane the frequency should be proportional to

Wtf?

[edit]Stuff on mixolydian and locrian appeared in this version [wtf?]

Some mail

[edit]It may have been an analysis by Spitta(?) of the highly chromatic B-minor fugue from WTC 1. It's easier to find hand-written than printed examples; e.g. the IMSLP scans for the Well-Tempered volume 1 show a facsimile of hand-written scores for the C# minor prelude where the same symbol is used for sharp and double-sharp (where the corresponding single sharp is always in the key signature), but the early printed edition uses x for double-sharp.

Also on the basis of a manuscript of WTK 1 but in this case Prelude 3 in C-sharp major: I saw that too, but figured that it wasn't a great example because (1) Every single note is sharped in the key signature so there'd be no occasion to use a single sharp, and (2) that particular prelude and fugue is said to have been originally in C major, so any curious features might be artifacts of transposition by just adding the 7-sharp key signature.

I see that there are some other noteworthy features: sharps in the key signature are still cancelled with naturals, not flats; and accidentals don't always carry through an entire measure by default (see the third-to-last bar of the prelude, or bar 9 of the fugue, for repeated Fx [notated #] in the left hand, and bar 13 for repeated Cx ["#"] in RH and B-natural in LH -- in each case it's the same voice so there's no question of the accidentals carrying from one voice to another on the same staff). On the other hand, in bar 7 of the second page -- where Bach actually has an Ax(!) en route to an E# minor cadence -- the tenor is surely meant to retain the Fx at least through the second beat. See also the RH in the previous bar, which seems to be an F-natural but is actually a cautionary F# (probably retained from the original C-major version; F-natural to D# is already somewhat exotic and even Bach might have nodded at F#-Dx when the latter was notated D#).

I finally find one example of an Fx (notated F#) cancelled with a natural: see the end of the third-to-last bar.

On a non-accidental matter, in the 5th system of the fugue, last bar, right hand: voice 2 has quarter note with stem up, voice 3 has a much larger *concentric* half note with stem down.

Fugue in B minor and the Prelude in C-sharp minor: Please note that what I remember from the B-minor fugue was a later published analysis (possibly by Spitta, and I think spread out over six staves for the four-part fugue!), not Bach's original. That fugue contains both a double-sharp (notated # as before) and a flat; I don't know if there's another example of that in WTC.

- What's going on at m. 48? Has the alto really fallen silent and is the tenor really jumping that high? And is the alto only speaking again at m. 51? I'm not sure I understand what's going on. My knowledge of the rules of the fugue could be better :)

Unfortunately I was not able to find there the one place in WTC where I've found double-flats (to see if Bach wrote b or bb). Perhaps surprisingly, B double-flats and even an Ebb occur in the Ab major pair in Book 2, towards the end of both prelude and fugue. But bach-digital, like IMSLP, has only the *first page* of the facsimile of the fugue! While for Book 1 it has the whole thing.

An answer

[edit]C♯ major prelude of BWV 848. m. 14 (RH), m. 22 (LH), m. 30 (RH), m. 33 (RH/LH), m. 34 (LH) (F in LH sharp or double sharp?), m. 34 (LH), m. 36 (RH), m. 37 (RH), m. 38 (RH), m. 40 (LH), m. 41 (LH), m. 44 (RH), m. 45 (RH), m. 71 (RH), m. 72 (RH), m. 76 (LH), m. 77 (LH), m. 98 (RH), m. 102 (LH)

Figured chords

[edit]

Piano pédalier

[edit]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJEwhUiNmS0

JEAN DUBÉ Oeuvres originales pour piano-pédalier de Alkan, Dubois, Franck, Liszt, Schumann

Piano Pédalier - works by Alkan, Dubois, Franck, Liszt, and Schumann / Jean Dubé: pedal piano

Label: Syrius Catalog No: SYUS 141446 Format: CD Release Date: 2013-02-12 Number of Discs: 1 Running time: 1 hr. 13 min. Mono/Stereo: Stereo UPC Code: 3491421414465

Album Summary

- Schumann, Robert : Etudes (6) in Canon Form for pedal piano, Op. 56

- Dubois, Théodore : Toccata for organ no 3 in G major

- Alkan, Charles-Valentin : Priere

- Franck, César : Prelude, Fugue and Variation for Organ in B minor, Op. 18

- Liszt, Franz : Fantasie und Fuge über den choral 'Ad nos, ad salutarem undam' aus der oper 'Der Prophet' von Meyerb

Performer Jean Dubé (Pedal Piano) Composers Théodore Dubois (1837 - 1924) Franz Liszt (1811 - 1886) Charles-Valentin Alkan (1813 - 1888) Robert Schumann (1810 - 1856) César Franck (1822 - 1890) Notes & Reviews: The first French prototypes of pedal pianos date from 1789, when Pontécoulant made a piano with a two-octave pedal board, followed (among others) by Erard in 1848. Sebastien Erard built the piano used for this recording, the No. 47588, in 1873. The amazing instrument had been put at the disposal of illustrious composers like Franck, Fauré, Ravel, and Milhaud. Notes & Reviews: Recording information: Dournazac (Haute-Vienne, France) (08/2011).

http://www.prestoclassical.co.uk/r/Syrius/SYR141446

OLIVIER LATRY Piano Pédalier

Oliver Latry Plays Alkan, Boëly, Brahms, Liszt, Schumann

CD Oliver Latry Plays Alkan, Boëly, Brahms, Liszt, Schumann Naïve / Naïve

RELEASE DATE October 25, 2011

http://www.prestoclassical.co.uk/r/Naive/V5278

PETER SYKES

Peter Sykes, pedal piano Southern Adventist University October 5, 2010 Prelude and Fugue in g minor, WoO 10 (1857) Johannes Brahms 1833-1897 From Studien für den Pedal-Flügel, op. 56 Robert Schumann 1810-1856 1. Nicht zu schnell 2. Mit innigem Ausdruck 3. Andantino – Etwas schneller 4. Innig 5. Nicht zu schnell 6. Adagio Skizzen für den Pedal-Flügel, op. 58 Schumann 1. Nicht schnell und sehr markirt 2. Nicht schnell und sehr markirt 3. Lebhaft 4. Allegretto Intermission From 11 Grandes Préludes, op. 66 Charles-Valentin Alkan 1813-1888 11. Lento, quasi recitativo From 13 Prières pour Orgue ou Piano à Clavier des Pedales, op. 64 Alkan 1. Andantino 11. Ingenuamente - Andantino Sonata, op. 65, no. 1 Felix Mendelssohn 1809-1847 Allegro moderato e serioso Adagio Andante. - Recit. Allegro vivace

http://www.bu.edu/cfa/music/faculty/sykes/

MARTIN SCHMEDING

http://www.naxosmusiclibrary.com/preview/catalogueinfo.asp?catID=ARS38011&path=2

Dalibor Miklavčič

http://mupa.hu/en/program/pedal-parade-organ-concert-by-dalibor-miklav-i-2013-02-24_19-30-bbnh

John Khouri

Jean Guillou

Blah

[edit]| G♭ | D♭ | A♭ | E♭ | B♭ | F | C | G | D | A | E | B | F♯ | C♯ | G♯ | D♯ | A♯ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F mode | II♭ | VI♭ | III♭ | VII♭ | IV♭ | I | V | II | VI | III | VII | IV | I♯ | V♯ | II♯ | VI♯ | III♯ |

| C mode | V♭ | II♭ | VI♭ | III♭ | VII♭ | IV | I | V | II | VI | III | VII | IV♯ | I♯ | V♯ | II♯ | VI♯ |

| G mode | I♭ | V♭ | II♭ | VI♭ | III♭ | VII | IV | I | V | II | VI | III | VII♯ | IV♯ | I♯ | V♯ | II♯ |

| D mode | IV♭ | I♭ | V♭ | II♭ | VI♭ | III | VII | IV | I | V | II | VI | III♯ | VII♯ | IV♯ | I♯ | V♯ |

| A mode | VII♭ | IV♭ | I♭ | V♭ | II♭ | VI | III | VII | IV | I | V | II | VI♯ | III♯ | VII♯ | IV♯ | I♯ |

| E mode | III♭ | VII♭ | IV♭ | I♭ | V♭ | II | VI | III | VII | IV | I | V | II♯ | VI♯ | III♯ | VII♯ | IV♯ |

| B mode | VI♭ | III♭ | VII♭ | IV♭ | I♭ | V | II | VI | III | VII | IV | I | V♯ | II♯ | VI♯ | III♯ | VII♯ |

Blah Blah

[edit]Continuo

[edit]Use of continuo instrument (in the singular) for the harmonic instrument that does the filling (also continuo player, in the singular)

Particularly the following excerpt "In the 17th century a wide variety of continuo instruments was used, including lute, theorbo, harp, harpsichord, and organ. By the 18th century the practice was more standardized: the bass line would be realized on a keyboard instrument and reinforced by a monophonic bass instrument, such as a lute, viola da gamba, cello, or bassoon. The continuo player not only completed the harmony but could also control rhythm and tempo to suit the particular conditions of a performance." Note how the "continuo player" (in the singular) means the guy who fills in the harmony ("realizes" the thorough bass) even though there may be several "continuo players" (in the plural), him and the guy or guys who double the bass line.

- article Nigel Fortune, Continuo Instruments in Italian Monodies, The Galpin Society Journal Vol. 6 (Jul. 1953), pp. 10-13

- A copy of the article (linked doesn't show any part of the article any more)

If you read through Nigel Fortune's article you see that it deals only with the harmonic instruments. Again the use of "continuo instrument" in the singular for the instrument that improvizes the chords above the bass line. The plural here is just because the article deals with several sorts of them.

Use of continuo instruments (in the plural) for all the members of the continuo group (also continuo players, in the plural)

This section is not empty

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Zondadari etc.

[edit]Anselme de Flandres

On Zondadari

Translation of Chrysanthos of Madytos's Great Theory of Music by Katy Romanou

Cavaliere signor marchese Fulvio Ghigi Zondadari "Riflessione fatte da Euchero Pastore Arcade sopra alla maggior facilità che travasi nell' aprendere il Canto con l'uso di un solfeggio di dodici monosillibi", Carlo Pecora, Venice, 1746

Mention of Zondadari in Translation of Galeazzi by Deborah Burton

Zondadari's system is Ut pa Re bo Mi Fa tu Sol de La na Si (as described by Giambattista Mancini)

Exposé de Jacques Chailley sur "Les Notations Musicales Nouvelles" fait à la Société de Musicologie le 24 juin 1949 et publié par Alphonse Leduc, Paris, décrit diverses tentatives:

- Roualle de Boisgelou (1764) Ut de Re ma Mi Fa fi Sol bi La sa Si

- Jean Hautstent (1907): Do de Re ri Mi Fa fo Sol sa La li Si

- Angel Menchaca (1911): Do se Re dou Mi Fa ro Sol fe La nou Si Menchaca's System

- Nicolas Obouhow (1915): Do lo Re te Mi Fa ra Sol tu La di Si

A General History of Music: From the Earliest Ages to the Present ..., Volume 2, By Charles Burney, p. 102

The Theoretical-Practical Elements of Music, Parts III and IV, By Francesco Galeazzi (Deborah Burton (Introduction), Gregory W. Harwood) University of Illinois Press

Music theory from Zarlino to Schenker: a bibliography and guide By David Damschroeder, David Russel Williams, Pendragon Press, p. 97 (on Galeazzi)

Examen critique des notations musicales proposées depuis deux siècles, By Joseph Raymondi, Paris, 1856

Hey there! (copied from talk page)

[edit]- Looks like user:Technical 13 has been indeffed as a sock master. "But he was always so nice! And so helpful!".

- Hello there! I'm working on a project trying to bring most of the coding on Wikipedia up to the most current standards (HTML5), and I noticed that your signature is using

<font>...</font>tags which were deprecated in HTML 4.0 Transitional, marked as invalid in 4.0 Strict, and are not part of HTML5 at all. I'd love to help you update your signature to use newer code, and if you're interested, I suggest replacing:

<small><span style="color:#C0C0C0;font-family:Courier New;">Contact </span><span style="color:blue;font-family:Courier-New;">[[User:Basemetal|Basemetal]]</span> <span style="color:red;font-family:Courier-New;">[[User talk:Basemetal|here]]</span></small>

- with:

<small style="font-family:Courier New;color:#C0C0C0">Contact [[User:Basemetal|<span style="color:blue">Basemetal</span>]] [[User talk:Basemetal|<span style="color:red">here</span>]]</small>

- which will result in a 188 character long signature (65 characters shorter) with an appearance of: Contact Basemetal here

- compared to your existing 253 character long signature of: Contact Basemetal here

- — Either way. Happy editing!

I also recommend, per addOnloadHook deprecation, you modify User:Basemetal/common.js and replace:

mw.util.addPortletLink ('p-tb', wgServer+wgArticlePath.replace("$1", "Special:PrefixIndex/"+wgPageName+"/"), 'Subpages');

with

mw.util.addPortletLink ('p-tb', mw.config.get('wgServer') + mw.config.get('wgArticlePath').replace("$1", "Special:PrefixIndex/" + mw.config.get('wgPageName') + "/"), 'Subpages');

As to your Orange bar of death issue, I'm still not entirely sure, but would be happy to dig into it for you and help you work through it.

<div class="usermessage plainlinks">[http://en.wikipedia.org/w/wiki.phtml?title=User:Basemetal/Sandbox&action=edit§ion=new To leave a message click here]</div>

Happy editing and I look forward to your replies... — {{U|Technical 13}} (e • t • c) 21:52, 2 December 2014 (UTC)

- Technical 13 Thanks for your help. I'll heed your advice re: signature and common.js. Looking forward to learning from you re: orange bar. Contact Basemetal here 22:24, 2 December 2014 (UTC)

- If you click on the [show] link in the orange bar above, what do you see? Can you give me a screenshot? Can you highlight the whole box and view selection source and post it to me? Thanks. :) — {{U|Technical 13}} (e • t • c) 22:33, 2 December 2014 (UTC)

- Technical 13

- I'll get back to you later. It's already 11:40 pm here. In the meantime, to answer your questions:

- The bar is not orange on my screen (whatever it is those {{Hst}} and {{Hsb}} templates are supposed to do)

- I see this:

<div class="usermessage plainlinks">[http://en.wikipedia.org/w/wiki.phtml?title=User_talk:Basemetal&action=edit§ion=new To leave a message click here]</div>, but that's probably not what you're asking. Screenshot? Highlight the whole box? (You mean in blue with my mouse?) View selection source? You might have to expand on that.

- Later.

- Contact Basemetal here 22:54, 2 December 2014 (UTC)

Signatures

[edit]Stuff

[edit]Franklin Taylor. Camillo Horn. Theodore Baker, A Biographical Dictionary of Musicians, 3rd Edition, 1919, page 415. Franz Anton Morgenroth. Francesco Galeazzi. Beethoven's nephew.

Hello!

[edit]Hi Basemetal. Yes, I self-identify as a grammar, spelling and punctuation stickler. But I guess I'm of the loony left of that tendency.

- No. I meant: What were you responding to? There was no 'who' nor 'whom' there that I could see. Were you in the right place? Contact Basemetal here 10:59, 4 November 2014 (UTC)

- It was about this entry in the young chap's blog. I would upvote the Eccleston Ninth Doctor. Those serials were were genuinely scary in the tradition of the original serials, but with much better production values. Alas, the subsequent Doctors and the serials lack any kind of internal plot and story arc consistency even within a singe show, let alone consistency within shows. But I digress...

- It was about this entry in the young chap's blog. I would upvote the Eccleston Ninth Doctor. Those serials were were genuinely scary in the tradition of the original serials, but with much better production values. Alas, the subsequent Doctors and the serials lack any kind of internal plot and story arc consistency even within a singe show, let alone consistency within shows. But I digress...

Armoured trains

[edit]I found you an armoured train success story at Battle of Mokra.

Lazy afternoon

[edit]- Mozart KV 516 Quintet in g (starts in minor, ends in the parallel major)

- Mozart KV 491 Piano Concerto in c (starts in minor, ends in minor, but simple variations-finale)

- Mozart KV 550 Symphony in g ("very square in its phrasing in the finale")

- Haydn Op. 50 No. 4 Quartet in f♯ ("looks like an exception but deliberate anachronism since the finale is a fugue")

- Mozart KV 516 (1st movement, "increasing animation of phrasing and texture" and... er... what is he saying?)

- Mozart KV 388 Serenade in c (1st movement, I give up... will have to listen to it to understand)

- Chopin Scherzo in b-flat/D-flat ("any polarity [between relatives] is no longer possible", that's Rosen)

- Chopin Fantasy in f/A-flat (same)

- Chopin Op. 58 Sonata in b ("chromatic blur between the two key areas", back to Double sharp)

- Alkan Sonata ("i-(VI-iv)-IV in the exposition and i-(V of III)-III in the recapitulation", Double sharp again and something about its programme)

- Alkan Symphony (progressive tonality from c to e-flat)

- Alkan Concerto (progressive tonality from g-sharp to F-sharp)

- Alkan Cello Sonata (progressive tonality again?)

- No progressive tonality here. The work starts in E major and ends in E minor with a vigorous virtuosic saltarella finale, which leads to an effect like the minuet-finale in Haydn's trio in f♯ (Hob:XV/26). Like I said, this is a very Classical work. Double sharp (talk) 01:11, 12 September 2016 (UTC)

- Ok. I got sorta confused by the logical articulation of your sentence, since you write "Alkan was one of the pioneers of progressive tonality (consider the Symphony in c-e♭ and the Concerto in g♯-F♯), so that I would classify his practice here certainly not as a return to a Classical spirit"... so the word "here" does not mean "in the Symphony and the Concerto", it means "in the Sonata"? For some reason I thought you meant his use of progressive tonality was not a return to the Classical spirit (I kinda wondered why you needed to say that) but one way to create a dramatic structure and that the same applied "here" and in the Cello Sonata. Since I thought "here" was the Concerto and the Symphony I was wondering (even though you did say the Cello Sonata was very Classical). So for some reason you put into relation what he does in the piano Sonata and in the Cello Sonata, even though you say those tricks don't usually work ("beyond novelty effects or programme") but they do in the Cello Sonata. It still not clear if you link the piano Sonata ("a work that takes the Romantic aesthetic to its logical extreme") and the Cello Sonata ("a very Classical work"), but hey.

- I think the Cello sonata does work, but mostly because it lacks a programme, apart from the Biblical quotation above the slow movement. (And one suspects that it cannot literally be the story of the work if there is one, because no one really wants to hear a piece that scientifically describes natural phenomena. At least, not before Satie's Embryons déssechés.) I'm sorry for not being clear. I intended to bracket the Cello Sonata and shove it to one side as a parenthesis, because it is a very unusual work for Alkan, but evidently I did not entirely succeed. Admittedly my knowledge of Alkan is mostly from the early virtuosic pieces that every pianist seems to find out about as a rite of passage before ignoring it, so I have not checked the tantalisingly-titled Sonatine Op. 61 to see if it continues this Classicising trend. But this is way off topic already. Double sharp (talk) 13:40, 13 September 2016 (UTC)

- Ok. I got sorta confused by the logical articulation of your sentence, since you write "Alkan was one of the pioneers of progressive tonality (consider the Symphony in c-e♭ and the Concerto in g♯-F♯), so that I would classify his practice here certainly not as a return to a Classical spirit"... so the word "here" does not mean "in the Symphony and the Concerto", it means "in the Sonata"? For some reason I thought you meant his use of progressive tonality was not a return to the Classical spirit (I kinda wondered why you needed to say that) but one way to create a dramatic structure and that the same applied "here" and in the Cello Sonata. Since I thought "here" was the Concerto and the Symphony I was wondering (even though you did say the Cello Sonata was very Classical). So for some reason you put into relation what he does in the piano Sonata and in the Cello Sonata, even though you say those tricks don't usually work ("beyond novelty effects or programme") but they do in the Cello Sonata. It still not clear if you link the piano Sonata ("a work that takes the Romantic aesthetic to its logical extreme") and the Cello Sonata ("a very Classical work"), but hey.

- No progressive tonality here. The work starts in E major and ends in E minor with a vigorous virtuosic saltarella finale, which leads to an effect like the minuet-finale in Haydn's trio in f♯ (Hob:XV/26). Like I said, this is a very Classical work. Double sharp (talk) 01:11, 12 September 2016 (UTC)

- Haydn Quartet Op. 50 No. 4 in F-sharp (1st movement)

- Mozart KV 271 Piano Concerto in E♭ (slow movement, c, despair)

- Mozart KV 364 Sinfonia Concertante in E♭ (slow movement, c, despair)

- Mozart KV 488 Piano Concerto in A (slow movement, f-sharp, despair)

- Mozart KV 516 String quintet in g (where?)

- Just about everywhere, but most obviously in the introduction to the sonata-rondo finale in G. Double sharp (talk) 01:11, 12 September 2016 (UTC)

- Mozart Zauberflöte, Pamina g aria ("and she prepares to commit suicide in the same key", afterwards?, will have to find out)

- Afterwards yes, in the second act finale (Du also bist mein Bräutigam). Double sharp (talk) 01:11, 12 September 2016 (UTC)

- Schubert Die schöne Müllerin (where? the whole cycle? which one more particularly? subversion of the affect of the modes)

- Most famously in #19. Double sharp (talk) 01:11, 12 September 2016 (UTC)

- Schubert Heiss mich nicht reden D 877 No. 2 (subversion of the affect of the modes)

- Haydn Emperor Quartet Op. 76 No. 3 (3rd movement, subversion of the affect of the modes)

- Mozart KV 595 Piano Concerto in B♭ (slow movement, "melody of utter simplicity" in major, subversion still?)

- These last four are not subversions in the previous sense since they do not have large areas in the minor mode, but they are very emotional melodies in the major mode that could perhaps draw a few tears – certainly Rosen claims that the piano trio Hob:XV/14, ii, could be used that way. Double sharp (talk) 01:11, 12 September 2016 (UTC)

- Ok. I was wondering if the "subversion" might not come from major showing itself capable of fulfilling a affective role traditionally thought to belong to minor, but apparently that's not what you meant.

- These last four are not subversions in the previous sense since they do not have large areas in the minor mode, but they are very emotional melodies in the major mode that could perhaps draw a few tears – certainly Rosen claims that the piano trio Hob:XV/14, ii, could be used that way. Double sharp (talk) 01:11, 12 September 2016 (UTC)

- Mozart KV 622 Concerto for clarinet (slow movement, "melody of utter simplicity" in major, subversion still?)

- Haydn Empreror Quartet OP. 76 No. 3 (2nd movement, Emperor Hymn, "melody of utter simplicity" in major, subversion again?)

- Haydn Piano Trio Hob:XV/14 (movement?, "melody of utter simplicity" in major, subversion again?)

- Slow movement.

- Schubert Op. 25, D. 795 No. 16. Die liebe farbe, b (B)

- Schubert Op. 25, D. 795 No. 17. Die böse farbe, B (b)

- Schubert Op. 25, D. 795 No. 18. Trockne Blumen, e–E–e

- Schubert Op. 25, D. 795 No. 19. Der Müller und der Bach, g–G

- Schubert Op. 25, D. 795 No. 20. Des Baches Wiegenlied, E

In the classical period modulations from a major key to the major key a 5th up and modulations from a minor key to its relative major appear in similar contexts. This may come from the asymmetry between major and minor in that period (I mean major being the senior partner) and from the way it was felt that the feeling of "brightening" you get when you move from a major key to the major key a 5th up and the feeling of "brightening" you get when you move from a minor key to its relative major were felt to be related. So my question: Must this way those two kinds of feeling of "brightening" were considered not equivalent but of the same order be considered entirely a cultural artifact specific to the music of that period (and those styles of music influenced by it) or is there some objective explanation for it?

- This has a lot to do with how the Classical style views the minor mode as essentially unstable, which is why so many pieces in the Classical era that start in a minor key end in the parallel major (most famously, Mozart's KV 516). When this does not happen, there must be a textural or formal reason why, with an added simplicity of phrasing or texture: for example, KV 491 ends in the minor, but has a simple variations-finale. Similarly, KV 550 is very square in its phrasing in the finale. Haydn's F-sharp minor trio likewise ends in the minor, but has a minuet for a finale. Haydn's quartet Op. 50 No. 4 looks like an exception, but to some extent this extraordinary work is a deliberate anachronism since the finale is a fugue (and also could be said to fit: after all, isn't a closing fugue an illustration of compositional virtuosity?)

- Like the subdominant, the minor mode tends to weaken the tonic, and plays a similar role. (For example, if one moves from I to v instead of V, the dominant is indeed established as a tonality, but the relation to the tonic is weakened and more strained: this is very much a dramatic thing.) Hence, in this system, moving to the relative major key increases the tension just as going to the dominant does in a major key. This is also helped by the increasing animation of phrasing and texture that always occurs in a Classical sonata, whether or not it is in the major or minor. For an easily spotted example, see KV 516, where the second subject takes a more expressive arcing form after the modulation from G minor to B-flat major is finally won. For a more subtle example, see KV 388, where the unease of the opening in C minor carries forth into the second group in E-flat major, with the increasingly irregular phrasing, as well as the bald juxtapositions of piano and forte outbursts on augmented sixth harmonies.

- As for how this changed over time, I cannot do better than quote Charles Rosen's The Classical Style (p. 26): "In the early part of the [eighteenth] century, the secondary key to C minor, for example, could be either the dominant minor (G minor), or the relative major (E flat major). But the dominant minor triad can never have the force of the major chord, and this weak relation almost totally disappeared by the end of the eighteenth century. The relative major now reigned alone as a substitute for the dominant in the minor mode. This situation, too, could not remain fixed for long. By the time of Schumann and Chopin, the minor mode and its relative major are often identified, considered as the same key, so that any polarity is no longer possible (as in the Chopin Scherzo in B flat minor/D flat major or the Fantasy in F minor/A flat major.) The instability of the function of the minor triad is clearly a force for historical change." So, indeed, this is a classical thing.

- The great frustration behind most Romantic sonatas in the minor (and yes, most of them are in the minor) is that Classically, they need to go to the relative major, but by the Romantic aesthetic that would be very much like the Red Queen, running to stay in the same place. Since the weight of tradition was still in force, though, what with the giant lumbering behind, most of these sonatas try to create a chromatic blur between the two key areas, such as Chopin's Op. 58. Of course, the problem here is that since the first group is agitatedly trying to go somewhere and the second group is so much more relaxed in its discursiveness (this sonata is very Italian...), the discourse almost feels over at the end of the exposition.

- A few works do try to take the Romantic aesthetic to its logical extreme: one of the interesting ones is the Alkan sonata, with its interesting key scheme of i-(VI-iv)-IV in the exposition and i-(V of III)-III in the recapitulation. Notwithstanding the general vulgar virtuosity of much of the development, I somehow doubt this scheme could have been invented without the clear programme stated ("Quasi-Faust": the characters are even given their own key areas as well as themes when first exposed, with Faust in i, Mephistopheles in VI, Gretchen in iv then IV, and God as a dominant pedal leading to III for the reprise of Gretchen's theme avec bonheur). It does work well: i-IV has the pull toward the subdominant beloved of the Romantic period while still increasing the energy by moving to a sharp-side key, and the move from i to III is polarised and dramatised by a huge dominant preparation (marked Le Seigneur, even). But this work is very exceptional due to its programme, as I mentioned. We must not forget also that Alkan was one of the pioneers of progressive tonality (consider the Symphony in c-e♭ and the Concerto in g♯-F♯), so that I would classify his practice here certainly not as a return to a Classical spirit, but simply as one among many ways to create one of the dramatic programmatic structures he loved so much. [Though I have my doubts whether they always work beyond the programme or novelty effects, outside the wonderful Cello Sonata Op. 47 that is an unacknowledged masterwork – though maybe the reason I think so is that it is very Classical in spirit, even in the programmatic slow movement.]

- OK, this seems to have expanded way beyond what I wanted it to be. I tried to stick with examples that I actually have memorised; they ought to be representative.

- You say: "the Classical style views the minor mode as essentially unstable". Is it again the same old old story that the minor chord is not a natural resonance or was it something entirely different? On a related note: When you personally hear a modulation from minor to relative does the brightening feel less, more, or equally intense than for a modulation from major to dominant? Or is there no way you can give a general answer and it depends on the actual modulation?

- It really depends on the style. In a Romantic sonata form, I tend to find the brightening very intense (for example in both sonatas of Chopin), even more intense than a major mode going to the dominant. In a Classical sonata form, I tend to find that the composer has muted it so that it has equal weight. I'll consider my beloved Haydn Quartet Op. 50 No. 4 in F♯ minor (if you don't know that quartet, you should!). The opening minor feels really unstable, as though it is crying out to be resolved. The syncopations continue through even when A major is reached, and so do the forzato outbursts within a general piano dynamic, and the whirling accompaniment feels disqueting to me. The lurch of this second group into D major at the start of the development feels more defiant, but it's not complete for me yet because it's not in the home key and the tonality slides away from D quickly. The tension keeps going through the recapitulation, with foreboding unisons. And then, the first subject reappears midway through the recapitulation, again forte, but now falling onto A♯ instead of A, and now the second group is shouted forte from the rooftops, we are in the home key, and this shift is the one that to me feels like the initial minor-relative major shift in a Romantic sonata form! (You really see here how, while for Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven C minor is most related to the parallel C major, for the next generation of Romantic composers it is most related to the relative E-flat major!)

- There has been much theoretical talk about the relative stability and naturalness of the major and minor modes, even if we restrict it to the period we are talking about (so taking the 1770s as an approximate cut-off). Frankly, I'm not sure I believe any of them, and I'm not sure if Haydn or Mozart did either. What I do find real is a difference of mood, that the major really does feel less clouded than the minor, and I am personally quite convinced that Haydn and Mozart would have felt that and used that in their music – consider how the greatest expressions of despair in Mozart are all in minor keys (to name a few: the C minor slow movements from KV 271 and KV 364; the F-sharp minor slow movement from KV 488; the G-minor string quintet KV 516; Pamina's G minor aria from Die Zauberflöte – and she prepares to commit suicide in the same key). I don't think this affect of the modes is really subverted until we get to Schubert, as Wittgenstein pointed out, most famously in Die schöne Müllerin. (For a less famous example that I love, try Heiss mich nicht reden, D 877 No. 2.) I'm not sure how much of this is because he is helped by the text, but a purely instrumental example occurs in the third movement of Haydn's Emperor Quartet Op. 76 No. 3. Perhaps that example helps me put a finger on how this happens – a purely expressive alternation, when you are sure, despite the sweetness of the music, that the major mode is a fiction that will pass. When hearing the major-mode section in the trio, you know that Haydn must return to reprise the opening period, and that he cannot stay in that heaven, and that impermanence makes that glimpse all the more bittersweet. Melodies of utter simplicity can have this effect too: I am affected somewhat that way by the slow movements of Mozart's concerti KV 595 and 622 (the clarinet one), as well as Haydn's Emperor Hymn (also in Op. 76 No. 3) and the Piano Trio Hob:XV/14. All are in major, but I find that they can induce tears.

- You say: "the Classical style views the minor mode as essentially unstable". Is it again the same old old story that the minor chord is not a natural resonance or was it something entirely different? On a related note: When you personally hear a modulation from minor to relative does the brightening feel less, more, or equally intense than for a modulation from major to dominant? Or is there no way you can give a general answer and it depends on the actual modulation?

- Could you point out one lied of the Schö. Mül. to listen to? Did that Wittgenstein mention one particular number? The cycle? Basemetal 20:09, 11 September 2016 (UTC)

- He didn't mention either, but #19 (Der Müller und der Bach) is probably the most famous example. It is the last five songs that have the most complex tonal relationships, and Rosen claims that they form a group tonally centered around E minor:

- 16. Die liebe farbe, b (B)

- 17. Die böse farbe, B (b)

- 18. Trockne Blumen, e–E–e

- 19. Der Müller und der Bach, g–G

- 20. Des Baches Wiegenlied, E

- This major–minor contrast has already been intimated, for example in #6 (Der Neugierige), #10 (Tränenregen), #12 (Pause), and #15 (Eifersucht und Stolz). In #16, the song is in B minor, with B major being used for memories. In #17, the song itself is in B major, but elements of B minor keep forcing themselves in in forte and fortissimo (for instance, the piano introduction has I brutally cut off by i, and the song's first modulation is to v instead of V). In #18, the E major is used for a fantastic future vision of self-pity, before we are brought back to reality by the dying away in E minor. #19 then starts in G minor, the largest harmonic distance between any two songs in the cycle. The confirmation of the miller's decision of suicide crucially happens in G major, though, which lets it stay in the E minor area. Finally #20: I can do no better than to quote Rosen, who says "The modal purity of the last song is a consolation, the lullaby that the stream sings as a requiem." Double sharp (talk) 01:05, 12 September 2016 (UTC)

- Could you point out one lied of the Schö. Mül. to listen to? Did that Wittgenstein mention one particular number? The cycle? Basemetal 20:09, 11 September 2016 (UTC)

Another thing about minor-key sonata forms

[edit]@Basemetal: If you are like Mozart, you probably want to save the major-key resolution to the finale (e.g. KV 388, KV 421, KV 466, and KV 516). So you then need to turn the major-key second subject to the minor mode in the recapitulation, and it will not accept this without a reformulation. (For one, tonicisation of ii is impossible in the minor, at least in the absence of an incredible amount of chromaticism to make the ♯![]() seem normal – for example, KV 312.) Fine examples of how to do this may be found in most of Haydn's double-variation sets. I would recommend the first movement of the C minor Piano Trio, Hob XV:13, except that that's the opposite way (minor to major). Double sharp (talk) 16:05, 16 September 2016 (UTC)

seem normal – for example, KV 312.) Fine examples of how to do this may be found in most of Haydn's double-variation sets. I would recommend the first movement of the C minor Piano Trio, Hob XV:13, except that that's the opposite way (minor to major). Double sharp (talk) 16:05, 16 September 2016 (UTC)

I've been reading your sandbox

[edit]So here's a list of double accidentals in WTC Book I:

- No. 3: C-sharp major (double sharps: really, all throughout)

- No. 4: C-sharp minor (double sharps: prelude, b. 11–13, 35–37; fugue, b. 5, 20, 39–41, 66, 69, 109)

- No. 8: E-flat minor (double flats: prelude, b. 26); D-sharp minor (double sharps: really, all throughout)

- No. 9: E major (double sharps: fugue, b. 13)

- No. 13: F-sharp major (double sharps: prelude, b. 8, 10–18; fugue: b. 9, 13, 14, 17, 19–22, 30)

- No. 14: F-sharp minor (double sharps: fugue, b. 5, 26)

- No. 18: G-sharp minor (double sharps: really, all throughout)

- No. 23: B major (double sharps: prelude, b. 7–10; fugue: b. 13, 14)

- No. 24: B minor (double sharps: fugue, b. 55)

The only double flat I found is in the E-flat minor prelude (b. 26). Assuredly the most tonally remote one is the F![]() in the B minor fugue. The symbol Bach uses is quite interesting, resembling a flat sign with two bowls (but without the second stroke in the modern sign

in the B minor fugue. The symbol Bach uses is quite interesting, resembling a flat sign with two bowls (but without the second stroke in the modern sign ![]() ). Sometimes Bach indeed notates double sharps with the single-sharp sign in the C-sharp major prelude and fugue, but since this was originally in C major this may have been an oversight. He uses the modern

). Sometimes Bach indeed notates double sharps with the single-sharp sign in the C-sharp major prelude and fugue, but since this was originally in C major this may have been an oversight. He uses the modern ![]() symbol in the D-sharp minor fugue, though sometimes it is rotated 90 degrees to make a plus-sign shape.

symbol in the D-sharp minor fugue, though sometimes it is rotated 90 degrees to make a plus-sign shape.

This must be an early thing. Mozart already uses the modern ![]() and

and ![]() symbols in his autographs. (If you are wondering which pieces I checked: KV 464/i and KV 428/ii. They are an F

symbols in his autographs. (If you are wondering which pieces I checked: KV 464/i and KV 428/ii. They are an F![]() and a B

and a B![]() ; the first is in three sharps and the second in four flats.) Double sharp (talk) 14:49, 9 September 2016 (UTC)

; the first is in three sharps and the second in four flats.) Double sharp (talk) 14:49, 9 September 2016 (UTC)

- By the way, the claim you will find in Hans Keller (I think) that Mozart would never have been seen dead with key signatures beyond four sharps or flats is wrong. I am not aware of a case of five or six sharps in Mozart, but five flats occur in the String Trio KV 563 (fourth movement, bars 145–176; B-flat minor), and six flats occur in the Variations for Piano KV 353 and 354 (both variation IX; E-flat minor). All of these are minore variations of works in B-flat or E-flat major. I find this somewhat amusing because the String Trio is one of the works he discusses in detail, although I am rather unimpressed by his analysis in general, which in its critique of KV 428 (for not developing into a Schoenbergian beginning from its initial tritone) shows clearly that it does not accept Mozart's musical language as a given (and neglects that all this expressive chromaticism is held tightly between the outer octave E-flats at the opening of the melody). There is a fragment of a Mozart piece in G-sharp minor, but it is very early: the notation is inaccurate (with single sharps instead of double sharps) and the key signature has only four sharps. Also, technically KV 488/ii is not the only Mozart piece in F-sharp minor, but since the other one is a fragment this also famous statement is less wrong. Double sharp (talk) 14:57, 9 September 2016 (UTC)

Random stuff from talk pages

[edit]- You might enjoy looking at Couperin's Nouveaux concerts. He says (p47) that although one could add a harpsichord or theorbo, nos. 12 & 13 always sound better with two viols and nothing more. He also figures some parts labeled "accomp." and leaves others for "violes sans accomp", although one such passage also has figures!

- There is a famous story (I think perhaps reported in Burney, but I 'm not sure of the reference) about Corelli deliberately offending some community where he was on tour, by performing his much-admired compositions with no chording instrument—only a cello on the bass line—because he found the playing of every single local keyboard player to be beneath contempt. The present case is rather different, but Andrew Manze has made a case for performing violin music from before about 1720 senza basso (on grounds that the continuo parts tend to be musically very simple, and even redundant, but also because of documentary evidence from the period), and has even recorded a sampling of music in this way, including Tartini's famous "Devil's Trill" sonata.

- The nature of the source must be taken into account, of course, but there is really a continuum involved here, rather than a black-and-white, "is it figured, or is it isn't?" (and please don't quote this as an example of potentially acceptable Wikipedia American English style ;-). Keep in mind that manuscripts tend to figured much more lightly than printed editions, and the supposition is that manuscripts were intended more for professional musicians, whereas printed editions were aimed at amateurs. Publishers, with an eye on potential sales, did not want to make their products difficult to use, and so supplied figures more liberally than manuscript copyists were prone to doing. Within this broad division, there are manuscripts with no figures at all, manuscripts with sparse figuring, etc. Variation (and even style of figuring) also varies by nationality. If you compare the bass figuring in the first (Hamburg) edition of Telemann's "Paris" Quartets with the later edition produced in Paris for Telemann's visit there, you will find not only are the specifically French figurings substituted for Telemann's German ones, but the Paris edition is also more densely figured. Perhaps this was because the publisher wanted to optimize sales, but equally it may have been a difference between French and German taste or custom. What I am trying to say is that (as you already know) unfigured bass in no way assumes omission of a chording instrument, but neither is the relative density of the figuring any indicator of the likelihood that the bass line might be played by a melody instrument alone. Ultimately, it is up to the performers to decide what they want to use to realize the continuo, and if Corelli once chose to use only his cellist in order to spite the local keyboardists in that one town, at his next stop he might have used organ, two harpsichords, harp, theorbo, three guitars, and glockenspiel for just the opposite reason. There simply isn't just one correct way to do things. To be sure, different performers are likely to have different opinions about the most effective way of realizing the continuo for any given piece of music, but at the same time circumstances may dictate less-than-optimal choices. When you have got a paying audience seated in the auditorium, are you going to stand by your principles when the pedals fall off of your Neupert harpsichord (as I once saw happen as a Brandenburg Concerto was about to get under way), or do you just go ahead and perform without the beast?

- Well, as a dyed-in-the-wool, indefatigable and fully operational HIP pedant I probably shouldn't be saying this, but sometimes what works in practice is preferable to what the textbooks tell us we are supposed to do. Even if the closest thing I have got to a reliable source is This General-reference Work, I am absolutely certain that no good musician in days of yore looked these things up in a rulebook before deciding how to proceed. Those books were written for rank beginners, and were only meant to serve as a rough guide until the student could gain sufficient experience to know how to proceed, including when it was preferable to violate the rule, rather than follow it. If we are going to base our performances today on such primers, then woe betide us.

- All of what you say is perfectly true. If I am making things sound direr than need be, it is just a bit of poetic exaggeration. What I am driving at here is that there is a wrong-headed attitude I encounter from time to time, according to which there is one and only one "correct" way to perform any given piece of early music. There are of course demonstrably unhistorical ways of performing music. As someone once observed, if the saxophone had existed in Bach's day, he probably would have written for it, but of course we cannot begin to imagine what he actually would have written, and it is a dead certainty he never imagined it as a substitute for the trumpet part in the Second Brandenburg Concerto. Whether he may have considered the part for a horn instead of a trumpet is quite a different matter. Insisting on a single "historically correct" way of performing is wrong-headed, in my opinion. Much better to think of a range of possibilities, within which there may be more and less plausible choices.

Random stuff continued

[edit]- Clement Miller's article in the current NG states twelve unequivocally: "Glarean's fame as a musical theorist rests above all on his Dodecachordon, published in Basle in 1547 by Heinrich Petri... This vast tome is divided into three books: book 1, based mainly on Boethius and Gaffurius, treats the elements of music, consonance and dissonance, and solmization; book 2 concerns the theory of 12 modes applied to plainsong and other monophony; book 3 discusses mensural music and the theory of 12 modes applied to polyphonic music" and "From [his visit to St Georgen] came the impetus to make an edition of Boethius's De musica and to develop his own system of 12 modes" ... "...the most fruitful results of Glarean's modal principles are found in the many instrumental compositions of late Renaissance composers who applied his ideas. Such men as Merulo, Padovano, and Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli wrote toccatas and ricercares in all 12 modes..." etc. Nowhere mentions 14. I don't have the illustration in front of me. Does it explain what the asterisk means?

- You can take a look at that first page here. There's no explanation as to the meaning of the asterisks on that page or immediately after since what follows is the dedication. Of course there might be something later on in the text. I'm not questioning Miller's statement. Of course I have not read the whole book.

- I believe you are correct that he recognized Hyperphrygius / Hyperaeolius as octave species rather than modes. Note the hyper- (over) vs hypo- (under) prefix. Here is a short bit on Hyperaeolian and Hyperphrygian from Book III, chapter 24 of the Dodecachordon: "Of the sixth combination, that of Hyperaeolian and Hyperphrygian, we have deliberately omitted an example, for none is to be found anywhere and it would be foolish to invent one, especially with so great a choice of modes; the tenor, too, would have an outrageous ambitus, actually exceeding all the remaining combinations of the modes by an apotome. Aside from this, in our previous book we have given an invented example, less for imitation than for illustration, so that the matter might be understood, not so that something of the sort might be attempted by anyone, a thing we find that no one has attempted." (tr. Oliver Strunk)

- Glareanus mentions requesting a hypothetical example in the Hyperaeolian from the famous composer Sixtus Dietrich in Constance, who obliged with a three-voice composition, printed in the Dodecachordon as Exx. 277, "O Domine Jesu Christe fili Dei". Glareanus also gives a second example from an actual composition (Exx. 278/279), a four-voice setting of the "Christe eleison" from a mass by Petrus Platensis (better-known today as Pierre de la Rue), though whether this is legitimately in Hyperaeolian is debatable, as can easily be seen in the example at the Thesaurus Musicarum Latinarum website, where the text of book 3 of the Dodecachordon is found here. The examples (for those who can read 16th-century notation) are found as GLADOD3 053GF/GLADOD3 054GF and GLADOD3 055GF /GLADOD3 056GF (each on two pages), respectively. I'm not immediately finding the passage in which Glareanus explains the horrible defects that caused him to reject this and its companion plagal mode (for which he did not even seek an artificial example), but I'm sure it's in there somewhere.

- Ah, I was looking in the wrong book. Glareanus's discussion of his reasons for omitting the Hyperaeolian and Hyperphrygian is found in book 1, near the very end, in chapter 21. He is discussing Aristoxenus, Ptolemy, and, especially, Martianus Capella, with whose 15 tones he finds some fault: "At nos sex principes cum singulis plagijs, ut Aristoxenus, ponemus, ut sit numerus 12. Omissis hypermixolydio, qui Ptolemaei est, et hyperaeolio hyperphrygioque quos posteri adiecerunt. Sunt autem principes nostri sex. Dorius, Phrygius, Lydius, Mixolydius, Aeolius et Iastius, siue (utroque enim modo reperias) Ionicus. Plagij item 6. cum [to hypo] compositi, Hypodorius, Hypophrygius, Hypolydius, Hypomixolydius, Hypoaeolius, Hypoiastius qui et Hypoionicus. Hi sunt ueri indubitati 12 Modi, de quibus sequentis libri commentationem suscepimus." The discussion is long, and my Latin weak, but the last sentence runs, "These are the undoubtedly true 12 modes, of which a commentary is undertaken in the following books."

- The thing that made me suspicious about Glareanus being a real family name was precisely that he came from the canton of Glaris. And it turns out he had another name namely Loris as I discovered by browsing through the corresponding articles on foreign language WPs (Latinized as Loriti according to the French WP or Loriti or Loritti or Loretti or Loritis according to the Spanish WP). Was that perhaps his real family name? Who knows with those humanists? Many 16th c. and 17th c. intellectuals tended to like Latin noms de plume, of if they thought they were really cool, Greek ones, e.g. Schwarzerd who was known as Melanchthon, the Greek translation of his name, e.g. the cartographer Cremer known as Mercator, the Latin translation of his name, and many many others; even the composer Schütz I think used at times Sagittarius, but I might be wrong; the article Renaissance Humanism fails to mention this, admittedly minor, fact. On whose authority do we have it that the Dodecachordon of the title refers to a 12 string instrument? I'm not questioning that it could, but the reason I asked is that I was wondering if the title has anything to do with the 12 modes, and if it is a 12 string instrument, I don't immediately see what instrument that would be. Ancient lyres tended to have 7 or 10 strings I thought. Finally the status of the hyperphrygian and hyperaeolian in Glarean's theory. There's no doubt, the excerpts, that as far as bona fide full modes he only accepts the first 12 in the table (and note that not only are the hyperphrygian and hyperaeolian asterisked but they also are not placed in the right sequence, but "at the back" as it were). So what exactly was their status and why did he include them in his table at all? Article Locrian mode (not me) says that he took the hyperaeolian as an octave species. That's fine, but I don't see how this could apply to the hyperphrygian: I don't see how the division into plagal and authent could apply to octaves species. As far as octave structure, the hyperphrygian would be identical to the lydian, wouldn't it? Unless I am mistaken, the preliminary table (see the smaller print where Glarean gives, next to his names, modal names assumed by other theorists, such as for example Martianus Capella, when they differ from his) seems to say that Glarean's hyperphrygian and hyperaeolian are not those of Martianus Capella. So his discussion may well reject some of the views of Martianus Capella, but how could he be rejecting specifically modes which he on the other hand equates (according to that table at least) with modes he accepts? But I'll keep the reference (Book 1, Chapter 21) for when I get my hands on an English translation of the work to see exactly what Glarean has to say and maybe finally to understand not only why he rejected those two but also why he thought necessary to include in the preliminary table modes he ended up rejecting. Do I understand correctly that the quote is from an English translation by Oliver Strunk? Finally: in WP "hyperphrygian mode" redirects to "hypodorian mode". Another WP mystery.

- First of all, formal (legal, usually patronymic) family names were only just coming into use in the 16th century in many European countries. When there was need for a person to differentiate himself from some other person with the same or a different name, it was often done informally (e.g., "Clemens non Papa" = that Clement guy who is not the Pope of the same name), though using a patronymic was also an often-used option. Naturally this can create all sorts of problems of identity when researching early sources, and Glarean himself supplies an example here, with Petrus Platensis (Pete from the Low Countries, you know the guy I mean!).

- Second, there is an English translation of the complete Dodecachordon by Clement Miller, in the series Musicological Studies and Documents 6 ([N.p.]: American Institute of Musicology, 1965). It is not available online, as far as I know, and I didn't have the opportunity to hike over to the library to consult it, which is why I used the Latin text from TML. The Strunk translation referred to is an excerpt, included in Oliver Strunk's excellent anthology Source Readings in Music History (Norton, 1950; new edition, with added material by Leo Treitler, Thomas J Mathiesen, James W McKinnon, Gary Tomlinson, Margaret Murata, Wye Jamison Allanbrook, Ruth A Solie, and Robert P Morgan, 1998).

- The confusion over mode names on WP (and elsewhere) in cases like this is to do with the fact that they are nonstandard. Glareanus grabbed names out of the air, so to speak, simply because he felt the need to supply terms for reference (and the same really applies to the Aeolian/Hypoaeolian and Ionian/Hypoionian, which are also arbitrary choices—the difference being that these names stuck). He uses them consistently throughout the Dodecachordon, but this usage does not necessarily apply in other sources and contexts, especially where ancient Greek terminology is concerned.

- The "octave species" issue is indeed confusing. The distinction between authentic and plagal ought not to apply here, and may well be one reason that Glarean does not give a separate discussion of his Hyperphrygian, since dismissal of the defective octave species for the Hyperaeolian is sufficient.

- But this is what I don't understand. I thought that the B to B octave is shared by the Hyperaeolian and the Hypophrygian, that they have the same octave B to B and that the difference is that the final is B in the case of the Hyperaeolian and E in the case of the Hypophrygian, and similarly that the Hyperphrygian and the Lydian both share the same octave F to F but that the final is B in the case of the Hyperphrygian and F in the case of the Lydian. If this is the case then how can mere consideration of the octave species lead to declaring the Hyperaeolian and the Hyperphrygian unsuitable if both share their octave with perfectly good and acceptable modes, namely the Hypophrygian and the Lydian respectively?

- A perfectly understandable terminological inconsistency on Glarean's part: the Hyperphrygian ought to be called the "Hypohyperaeolian".

- As far as it goes, you are correct. The distinction has to do with the inability to divide the octave into an appropriate tetrachord/pentachord pair. By "appropriate" I mean that one of them must begin on the assigned mode final (what this boils down to is that the interval between the mode final and the fifth note above may not be a diminished fifth). This is the trick that discriminates between the octave species in the Hyperaeolian/Hypophrygian and Hyperphrygian/Lydian pairs. I still haven't gotten to the library to consult Clement Miller's translation, but I have found an English translation of the entire concluding chapter of book 1 of the Dodecachordon, together with a commentary. This is in volume 2, chapter 3 of John Hawkins's General History of the Science and Practice of Music in Five Volumes (London: T. Payne & Son, 1766), which can be found online here. Hawkins adds a summary table of the octave species on p. 423. I hope this helps clarify this matter.

Chiffrage

[edit]Bonjour.

Il y a plusieurs années que j'ai contribué à plusieurs articles sur l'harmonie et il m'est aujourd'hui difficile de me souvenir de tout. Pouvez-vous m'indiquer le lien menant à l'article contenant l'illustration qui semble poser problème ? J'ai besoin de remettre cet exemple dans son contexte (contenu de l'article, etc.) avant de vous répondre et de procéder éventuellement aux corrections qui s'imposent. Merci d'avance. Cordialement. --Yves30 Discuter 16 mai 2013 à 17:52 (CEST)

- Bonjour. L'article en question est celui-ci mais en fait il se peut que vous ayez, avec votre chiffrage en chiffres romains, tenté d'indiquer non les fondamentales des accords mais leur fonction (tonique, dominante, sous-dominante)? Dans ce cas il n'y a pas d'erreur. Cordialement. Contacter Basemetal ici 16 mai 2013 à 22:10 (CEST)

- Oui, c'est ça. En fait le chiffrage "traditionnel" se trouve entre les deux portées. En revanche, au-dessous de la portée en clé de fa, figurent deux lignes : TP (tonalité précédente) et NT (nouvelle tonalité). Sur chacune d'elles est simplement indiquée en chiffres romains la fondamentale de l'accord (indépendamment de son état, fondamental ou renversement). Par exemple, dans l'exemple N, la mesure T (accord de transition) contient deux accords synonymes (les hauteurs sont les mêmes par enharmonie) ; le premier (dont les notes sont entre parenthèses) a sol pour fondamentale : il s'agit bien du Ve degré de la TP (tonalité précédente, à savoir do) ; le second a do # pour fondamentale : il s'agit bien du Ve degré de la NT (nouvelle tonalité, à savoir fa #). J'espère vous avoir apporté les précisions que vous souhaitiez. Cordiales salutations. Yves30 Discuter 16 mai 2013 à 22:53 (CEST)

You have a very cool userpage :)

[edit]Taklu

[edit]Hi there. William Erskine, in his "History Of India Under Humayun" has this:- "The inhabitants were expelled, their provisions, money and property seized by the domineering Taklus, and the floors of their houses dug up to discover hidden treasure...". Do you know what the capitalised "Taklu" means? SemperBlotto (talk) 15:07, 4 June 2013 (UTC)

Elsewhere on a Google book search:- "The well,to,do have drawing,room suits, dining,tables; chairs, almirahs, dressing tables, beds, etc., while the less affluent usually manage with items of furniture like taklus (wooden divans), morhas (chairs made of reeds), cane chairs and ..." Is this the origin of the word? SemperBlotto (talk) 15:12, 4 June 2013 (UTC)

- I don't know. You've found some interesting examples! The current use of the word comes from Hindi but of course in Hindi itself it may have a longer history. One would have to look at an etymological dictionary for Hindi. Basemetal (talk) 15:16, 4 June 2013 (UTC)

Latin pitch accent?

[edit]These are a few questions I posted at the Reference Desk of the English WP (though I wasn't the OP) in the context of a thread regarding the relation between the sound of Latin and that of its daughter languages. (Even when the statements are not strictly speaking questions, they actually are, as I believe you can tell.)

- I read somewhere, but so long ago that I couldn't give you a source, that, hypnotized by Greek grammar, ancient Latin grammarians uniformly described the Latin accent as a pitch accent, but that they were almost certainly uniformly wrong, and were certainly wrong for vulgar Latin.

- On the other hand could it be that literary Latin became influenced by Greek to such an extent that it adopted a pitch accent?

- Literary Latin did after all adopt an entirely foreign quantitative metric for Latin poetry (which completely replaced the stress based Saturnian verse) and it is known that literate Romans were pronouncing Greek borrowings in Latin using Greek phonemes that did not otherwise exist in Latin (e.g. pronouncing Greek upsilon like French 'u', or aspirate pronunciations of ph, th, ch, and rh).

- Someone with access to Latin grammatical literature may be able to shed more light on this.

- One related question I find intriguing is that, this being the case, you would expect Latin grammarians to also try to find in Latin an equivalent to the circumflex/acute distinction of Greek.

- The one way this would be likely to happen (since the place of the Latin accent is completely determined by the quantity of the penultimate syllable) would be to describe the accent as a circumflex if the penultimate had a long vowel, but as an acute if the penultimate syllable was short and the antipenultimate carried a long vowel, as this would result from the simplest pitch accent rule (ignore the last syllable and raise the mora two moras back).

- Again, if someone has access to Latin grammatical literature, I'd be very curious if any such description is found anywhere.

- Something to possibly watch for would be if they used Greek terms such as paroxytone, proparoxytone or properispomenon to describe the Latin accent, e.g. if they described the Latin accent as a properispomenon if the penultimate had a long vowel, a proparoxytone if the penultimate was a short syllable, or a paroxytone if the penultimate was a long syllable but had a short vowel.

I figured there are probably more people able to answer such questions here than there. Thanks for any help. Basemetal (disputatio) 04:15, 29 Octobris 2015 (UTC)

- It is agreed that classical Greek had a pitch accent, but this was to change: modern Greek has a stress accent in the same position. The most likely period for such a change is when Greek spread rapidly to speakers of other languages (early to mid Hellenistic period: Robert Browning, Medieval and Modern Greek (1969) p. 33, sees signs of the change "by the end of the third or beginning of the second century BC"). If that's the case, classical Romans read descriptions of Greek with a pitch accent, but actually heard Greek with a stress accent. So their use of that terminology to describe a stress accent in their own language would be no surprise at all! My answer on that point, then, would be that literary Latin didn't adopt the Greek pitch accent, which was already largely a thing of the past.

- Thinking further, the effect of this change in Greek was that the acute and circumflex were no longer distinguished in pronunciation. As to whether a parallel distinction in Latin was ever hypothesised, I don't know! Andrew Dalby (disputatio) 14:50, 29 Octobris 2015 (UTC)

- Thank you Andrew. As a side note: for the distinction between acute and circumflex to disappear, that is for them to merge, it is not enough that the pitch accent be replaced by a stress accent, as you could still, in principle, have a "stress" acute (resp. circumflex) if the stress accent applied only to the 2nd (resp. 1st) mora of a long vowel. It is also necessary that the distinction between long and short vowels disappear. Basemetal (disputatio) 20:14, 29 Octobris 2015 (UTC)

- I think there is no such principle. I don't know of any language in which a stress accent is applied specifically to the second mora of a long vowel. Note that the Wikipedia article en:Stress (linguistics) describes stress as placed on syllables, not vowels, let alone half-vowels. Andrew Dalby (disputatio) 10:14, 30 Octobris 2015 (UTC)

- Ok, but the question still remains whether in Greek the loss of the distinction between circumflex and acute preceded or coincided with the entire reorganization of the ancient Greek vowel system, which, incidentally, did not only involve the loss of the distinction between long and short vowels but also vowel shifts which ultimately transformated a 7 vowel color system into a 5 vowel color system. I can see that irregular spellings (for example) can tell you the latter has happened or is happening, along with things like transcriptions of foreign words from languages such as Hebrew, Aramaic, Persian. On the other hand I'm not clear what independent and direct signs of change there can be for the former (i.e. the loss of the distinction between acute and circumflex), except that when the latter processes are complete there can no longer be any room for a distinction between acute and circumflex, as it depends on the existence of vowel quantity distinctions. I'm curious how Robert Browning can tell when that happened. I'm talking of specific signs, not a priori arguments such as that "it must have happened" when non-Greek speakers started adopting Greek as a lingua franca. Basemetal (disputatio) 20:44, 30 Octobris 2015 (UTC)