User:Arayofsunshine12/sandbox

Week 8

[edit]Article Evaluation

[edit]After reading the three Wikipedia articles, among several others, I gained a more enhanced knowledge of the quality of articles and what constitutes a good article versus a bad one. To begin with, both the Public Health and Sugar Substitutes articles contain relevant information throughout. However, there are some references in the sugar substitutes article that were not fully developed and were possibly difficult to understand in the context of the topic, given their lack of explanation (i.e. metabolic disorder and cancer sections). As for neutrality, the public health article does a very good job of providing substantial background and history on public health, making it a very impartial and informative article. Meanwhile, the sugar substitutes article does not balance the two sides of the controversial issue well. For example, it explains the uses of sugar substitutes relatively well. But, it then inadequately mentions health effects and cites single, unexplained, evidence that many of these health effects cannot conclusively be correlated or causal links with sugar substitutes. Then, it continues to suggest that consuming sugar substitutes is bad but that consuming sugar instead is not much better. Thus, we get imbalanced perspectives and a seemingly biased approach to the issue. Most of the citations I checked worked for both articles, but one or two of the citations I looked at for the Sugar substitutes article brought up the opposing side of an issue immediately following their previous statements, which the Wikipedia article did not address. While both articles mostly used reliable sources, a few sections of the sugar substitutes article lacked citations in information/fact-heavy paragraphs. I wish the sugar substitutes article included more background about the approval and concerns with certain substitutes: some were much more heavily represented than others.

As for the additional article I read, which was on the company 23andMe, I found both some positive and negative aspects about the article. To begin with, the article does a good job of providing significant context and information about the company, keeping a mostly impartial stance. It both presents the origins of the company as well as the legal struggles the company faced over the past several years. It addresses the financial issue, letting the reader know that the founder of the company was married to the co-founder of Google at the time when Google invested nearly four million dollars into the business. Meanwhile, the article could definitely be expanded. For example, I think the article might benefit from discussing the reception of the product by the consumer more deeply, presenting both positive and negative responses to remain neutral. It could also go into more detail on the background of genetic testing so that the reader can better understand the motives and methods used by the company. The article also represents each section relatively equally and uses multiple citations in nearly every paragraph. While most of these citations come from reliable sources, however, several come from potentially biased or less-than-adequate resources, such us less commonly cited newspapers and websites. Thus, the editors might be better off doing more in-depth research on the company if possible. The talk page discusses various issues throughout the article, most specifically making sure not to have the article appear as an ad for the company, expanding the article to discuss more of the medical history related to the topic, etc. There were some arguments about citations and information. The article is part of several WikiProjects, most notably Wiki Project Medicine; it was rated Start-Class by the projects. This article discusses the topic in a similar way to that of ours in class, but it goes into more detail on the background and legal battles of the topic.

| This is a user sandbox of Arayofsunshine12. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |

Content Gap Assignment

[edit]I think a content gap is what it suggests: a gap in content. More specifically, I think it refers to lacking information that is relevant to the topic being written about. Some ways to identify them may include first seeing if critical events are missing from a chronological timeline in an article, looking for if there are places where the article jumps from one subsection to another without clear connection or background information, and using other sources to see if there are important pieces of content missing from the wikipedia article. A content gap may arise if an editor/author of an article is well-informed/an expert on the issue: he/she may not realize that certain content/background information may seem like second nature to him/her but might be foreign to the average person. Also, content gaps can arise if there is a lack of communication amongst the authors of an article, if it is split up amongst several authors. These problems can be solved in several ways. Most notably, greater communication can solve both problems: if an editor/author communicates with other editors who may not be experts in the given topic, they can aware the author of gaps. At the same time, if a group of authors has better communication within it, these gaps are less likely to occur. I don't think it matters who writes wikipedia, as long as they are well-trained to do so, well-informed on their topic, and are willing to listen to other editors to improve the article. Being unbiased on Wikipedia means that authors present their topic with a neutral and informative stance, not taking a side on the issue. This is still different from my definition of bias, as I would still present both sides of the issue, whereas these articles are meant to be solely informative and neutral throughout.

Week 9

[edit]Finding a Topic

[edit]Healthcare Worker's Disease

[edit]This article has not yet been created, so I would both establish and then contribute several aspects to the article. For one, I would define the disease briefly at first and give a quick background of SARS and its relationship to the disease. After establishing the disease in the proper context, I would analyze the specific details of the disease and the chronological events that led the issue to expand throughout Toronto amongst workers. In doing so, I would examine the causes of the disease, the ethics behind the treatment of diseases knowing the risk for such heatlhcare worker's diseases, and the ways in which the disease can be prevented and avoided. Lastly, I would refer the reader to similar situations that have taken place regarding other infectious diseases and give them a starting point to locating similar diseases that have arisen in the past and that may threaten workers' health in the future.

Bibliography for Healthcare Worker's Disease:

Rose Cipollone

[edit]This article also does not exist yet. While there are several articles that mention and even give brief backgrounds on the life of Rose Cipollone and discuss the law suit revolving around her death, no article is specifically dedicated to the woman herself. I would create an article solely dedicated to Rose, which would obviously still include references to the events in which she is significant and the role she played in the tobacco industry's advertising campaign; but I would also look back at her childhood and life growing up, both to give greater context to the issues later on in her life and to examine possible origins of her smoking habit, sickness, and eventual death.

Bibliography for Rose Cipollone:

Copyedit Assignment

[edit]My article has not yet been started, so I was unable to edit it for grammatical errors. However, I simulated the copyedit process by going through my own sandbox and making grammatical errors along the way. As for my article, there are certain sections I plan on adding and expanding as I work on the project. The first section will simply be an overview defining the disease and giving a slight amount of context on the topic. I will then go on to have a background/origins section to examine where and how the disease came to be. Afterwards, I will go deeper into the topic by analyzing the course of the disease in Toronto and comparing it to other similar cases throughout history worldwide. I will finally finish the article with a section on suggested prevention and treatment methods for the disease to prevent a situation like Toronto's from happening again.

First Draft: (on mainspace now!) 2002–2003 SARS outbreak among healthcare workers

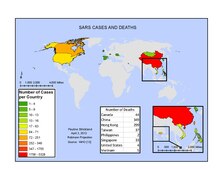

[edit]This article discusses the development of Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in healthcare workers—most notably in Toronto hospitals—during the global outbreak of SARS in 2002-2003. The rapid spread of the disease among healthcare workers (HWCs) contributed to dozens of identified cases, some of them fatal.[6] Researchers have found several key reasons for this development, such as the high-risk performances of medical operations on patients with SARS, inadequate use of protective equipment, psychological effects on the workers in response to the stress of dealing with the outbreak, and lack of information and training on treating SARS.[7] Lessons learned from this outbreak among healthcare workers have contributed to newly developed treatment and prevention efforts and new recommendations from groups such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)A map of SARS cases and deaths around the world regarding the global population, not just HCWs.BackgroundSARS spread around the world from the Guangdong Province of China, to multiple locations, like Hong Kong and then Toronto, Canada from 2002-2003.☃☃ The spread of SARS originated from a doctor residing in a hotel in Hong Kong to other tourists staying in the same hotel, who then travelled back home to locations like Toronto (without knowing that they had the disease).☃☃ The growing number of cases in Toronto gave HCWs a significant challenge, as they were tasked with stopping the spread of the disease in their city. Unfortunately, this unprepared-for challenge led several hospitals in the city and in the surrounding Ontario region to see dozens of cases of SARS arise not only in typical patients but also in HCWs themselves.☃☃Noticing this development, on March 28, 2003, the POC (Provincial Operating Centre) in Ontario established a set of SARS-specific recommendations and suggestions for all hospitals in Toronto in order to guide them on how to best avoid the transmission of SARS among HCWs.☃☃ They hoped that these initiatives would protect HCWs from the disease, allowing them to continue treating other SARS-infected patients without putting themselves at risk.A study published in 2006, however, suggests that these directives were not fully practiced and/or enforced, causing many HCWs to still get the disease.☃☃☃☃ The study followed 17 HCWs in Toronto hospitals who had developed the disease and interviewed 15 of them about their habits and practices during the time of the outbreak.☃☃ Specifically, the study involved asking the HCWs questions regarding the amount of training they had received on dealing with SARS cases in a cautionary way, how often they used protective equipment, etc.☃☃ In the end, results showed that the practices of these HCWs did not fully meet the recommendations set forth by the POC, providing greater evidence that these poor practices (described below) led to the development of the disease in HCWs more than anything else.☃☃Causes of transmissionHigh-risk performanceMany HCWs became more susceptible to contracting the disease due to their operations and high-risk interactions with SARS patients.☃☃ Many of these interactions, such as caring for a patient directly or communicating with the patient, create high-risk scenarios in which the HCWs have many ways of becoming infected.☃☃ There are three main categories of High-Risk Performance: direct contact by patient, indirect contact by patient, and high-risk events.☃☃☃☃Direct contact by patientDirect contact and resulting transmission of the disease "occurs when there is physical contact between an infected person and a susceptible person".☃☃ This direct contact can be various types of contact involving blood or bodily fluids,☃☃ but some SARS-specific examples include when a patient receives supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation with the aid of HCWs.☃☃ . These require the direct contact of a patient with a HCW, making it a viable method of SARS transmission.☃☃ As direct contact is the most common form of high-risk performance, all seventeen HCWs participating in the study encountered some sort of direct contact with a patient in the 10 days before getting the disease.☃☃High-risk proceduresHigh-Risk Procedures include intentional actions that are taken by the HCW in order to help a patient.☃☃ They are considered high-risk because the chances of a disease being transmitted during these procedures are far greater than typical direct or indirect contact with a patient.☃☃ While there are myriad high-risk procedures, those that are SARS-specific include intubation, manual ventilation, nebulizer therapy, and several others.☃☃ As was highlighted in the study, fourteen of the seventeen HCWs taking part in the study were involved in some high-risk procedure in the 10 days before getting the disease.☃☃Indirect contact by patientWhile direct contact involves the physical contact of two people, indirect contact does not.☃☃ Instead, indirect contact "occurs when there is no direct human-to-human contact," and it can involve contact of a human with a contaminated surface,☃☃ which are known as fomites.☃☃ The most plausible cases of transmission through indirect contact are when an HCW or healthy person touches a surface contaminated with droplets from an infected patient's sneeze or cough or inhales those droplets themselves. ☃☃ At the same time, if the droplets come in contact with the healthy person's mouth, eye, or nose, the healthy person also risks becoming ill.☃☃ Other types of high-risk events include diarrhea and vomiting, which can very easily contaminate a HCW with bacteria or fluid that contains the SARS disease through indirect contact.☃☃ Regarding coming into contact with contaminated surfaces or fomites, many HCWs had habits of wearing jewelry, eating lunch on site or in designated cafeterias, wearing glasses, using makeup, etc., which are all potential new fomites that could foster the transmission of disease.☃☃ . Just like with direct contact, all seventeen HCWs participating in the study encountered some type of high-risk event in the 10 days before getting the disease.☃☃Equipment inadequacyOne large guideline for HCWs in Toronto hospitals was the use of sufficient and protective equipment to avoid transmission of the disease.☃☃ The most widely suggested and used pieces of equipment were masks, gowns, gloves, and eye protection.☃☃ While these pieces of equipment were used by most HCWs, they were not always used—if at all—by everyone, allowing SARS transmission to take place more easily.☃☃An example of typical surgical masks used by HCWs when interacting with patients.MasksSurgical masks were suggested to be used by both HCWs and patients. This is because the specifically recommended type of masks do a good job of preventing one's own bacteria and fluid from escaping into the air—keeping both a patient and a HCW's bacteria and fluid to themselves.☃☃ Less intentionally but also important, these masks discourage patients and HCWs from putting their fingers or hands in contact with the nose and mouth, which could usually allow bacteria to spread from the hand to these areas.☃☃ Contrary to popular belief, some types of masks do little to prevent fluid and bacteria from coming in contact with the wearer of the mask, but they can still help prevent airborne infection. Therefore, it is important that both the patient and the HCW wear the mask. However, the aforementioned study's results indicate that HCWs wore them much more often than the patients themselves; in fact, fourteen of the HCWS always wore their mask, while only 1 of the patients always wore his/her mask.☃☃An example of a hospital gown worn by HCWs and patients.GownsHospital gowns are another piece of equipment used by HCWs during the outbreak.☃☃ Used mostly for those who are having trouble changing/moving their lower body, gowns are easy for patients to put on when they are bedridden.☃☃ They are also helpful for HCWs to attempt to avoid contamination, as the gowns can be removed and disposed of easily after an operation or interaction with a patient.☃☃ While seemingly less critical than masks, gowns were worn nearly the same amount by HCWs as masks.☃☃An example of typical disposable medical gloves worn often by HCWs.GlovesMedical gloves, like masks and gowns, also serve the purpose of preventing contamination of disease by blocking contact between the hands and the various bacteria, fluid, and fomites that carry the disease.☃☃ HCWs can again, like gowns, easily dispose of and change gloves in order to help improve and maintain good sanitary conditions.☃☃ Compared to all of the other pieces of equipment, gloves were worn the most often by HCWs who contracted the disease.☃☃A general type of eye-shield used by HCWs to prevent infection through the eyes.disease by blocking contact between the hands and the various bacteria, fluid, and fomites that carry the disease.[8] HCWs can again, like gowns, easily dispose of and change gloves in order to help improve and maintain good sanitary conditions.[9] Compared to all of the other pieces of equipment, gloves were worn the most often by HCWs who contracted the disease.[10]

Background

[edit]SARS spread around the world from the Guangdong Province of China, to multiple locations, like Hong Kong and then Toronto, Canada from 2002-2003.[11] The spread of SARS originated from a doctor residing in a hotel in Hong Kong to other tourists staying in the same hotel, who then travelled back home to locations like Toronto (without knowing that they had the disease).[12] The growing number of cases in Toronto gave HCWs a significant challenge, as they were tasked with stopping the spread of the disease in their city. Unfortunately, this unprepared-for challenge led several hospitals in the city and in the surrounding Ontario region to see dozens of cases of SARS arise not only in typical patients but also in HCWs themselves.[13]

Noticing this development, on March 28, 2003, the POC (Provincial Operating Centre) in Ontario established a set of SARS-specific recommendations and suggestions for all hospitals in Toronto in order to guide them on how to best avoid the transmission of SARS among HCWs.[14] They hoped that these initiatives would protect HCWs from the disease, allowing them to continue treating other SARS-infected patients without putting themselves at risk.

A study published in 2006, however, suggests that these directives were not fully practiced and/or enforced, causing many HCWs to still get the disease.[15][16] The study followed 17 HCWs in Toronto hospitals who had developed the disease and interviewed 15 of them about their habits and practices during the time of the outbreak.[16] Specifically, the study involved asking the HCWs questions regarding the amount of training they had received on dealing with SARS cases in a cautionary way, how often they used protective equipment, etc.[16] In the end, results showed that the practices of these HCWs did not fully meet the recommendations set forth by the POC, providing greater evidence that these poor practices (described below) led to the development of the disease in HCWs more than anything else.[15]

Causes of transmission

[edit]High-risk performance

[edit]Many HCWs became more susceptible to contracting the disease due to their operations and high-risk interactions with SARS patients.[16] Many of these interactions, such as caring for a patient directly or communicating with the patient, create high-risk scenarios in which the HCWs have many ways of becoming infected.[16] There are three main categories of High-Risk Performance: direct contact by patient, indirect contact by patient, and high-risk events.[16][17]

Direct contact by patient

[edit]Direct contact and resulting transmission of the disease "occurs when there is physical contact between an infected person and a susceptible person".[17] This direct contact can be various types of contact involving blood or bodily fluids,[17] but some SARS-specific examples include when a patient receives supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation with the aid of HCWs.[16] . These require the direct contact of a patient with a HCW, making it a viable method of SARS transmission.[16] As direct contact is the most common form of high-risk performance, all seventeen HCWs participating in the study encountered some sort of direct contact with a patient in the 10 days before getting the disease.[16]

High-risk procedures

[edit]High-Risk Procedures include intentional actions that are taken by the HCW in order to help a patient.[16] They are considered high-risk because the chances of a disease being transmitted during these procedures are far greater than typical direct or indirect contact with a patient.[16] While there are myriad high-risk procedures, those that are SARS-specific include intubation, manual ventilation, nebulizer therapy, and several others.[16] As was highlighted in the study, fourteen of the seventeen HCWs taking part in the study were involved in some high-risk procedure in the 10 days before getting the disease.[16]

Indirect contact by patient

[edit]While direct contact involves the physical contact of two people, indirect contact does not.[17] Instead, indirect contact "occurs when there is no direct human-to-human contact," and it can involve contact of a human with a contaminated surface,[17] which are known as fomites.[18] The most plausible cases of transmission through indirect contact are when an HCW or healthy person touches a surface contaminated with droplets from an infected patient's sneeze or cough or inhales those droplets themselves. [19] At the same time, if the droplets come in contact with the healthy person's mouth, eye, or nose, the healthy person also risks becoming ill.[17] Other types of high-risk events include diarrhea and vomiting, which can very easily contaminate a HCW with bacteria or fluid that contains the SARS disease through indirect contact.[16] Regarding coming into contact with contaminated surfaces or fomites, many HCWs had habits of wearing jewelry, eating lunch on site or in designated cafeterias, wearing glasses, using makeup, etc., which are all potential new fomites that could foster the transmission of disease.[16] . Just like with direct contact, all seventeen HCWs participating in the study encountered some type of high-risk event in the 10 days before getting the disease.[16]

Equipment inadequacy

[edit]One large guideline for HCWs in Toronto hospitals was the use of sufficient and protective equipment to avoid transmission of the disease.[15] The most widely suggested and used pieces of equipment were masks, gowns, gloves, and eye protection.[16] While these pieces of equipment were used by most HCWs, they were not always used—if at all—by everyone, allowing SARS transmission to take place more easily.[14]

Masks

[edit]Surgical masks were suggested to be used by both HCWs and patients. This is because the specifically recommended type of masks do a good job of preventing one's own bacteria and fluid from escaping into the air—keeping both a patient and a HCW's bacteria and fluid to themselves.[20] Less intentionally but also important, these masks discourage patients and HCWs from putting their fingers or hands in contact with the nose and mouth, which could usually allow bacteria to spread from the hand to these areas.[16] Contrary to popular belief, some types of masks do little to prevent fluid and bacteria from coming in contact with the wearer of the mask, but they can still help prevent airborne infection. Therefore, it is important that both the patient and the HCW wear the mask. However, the aforementioned study's results indicate that HCWs wore them much more often than the patients themselves; in fact, fourteen of the HCWS always wore their mask, while only 1 of the patients always wore his/her mask.[16]

Gowns

[edit]Hospital gowns are another piece of equipment used by HCWs during the outbreak.[16] Used mostly for those who are having trouble changing/moving their lower body, gowns are easy for patients to put on when they are bedridden.[21] They are also helpful for HCWs to attempt to avoid contamination, as the gowns can be removed and disposed of easily after an operation or interaction with a patient.[22] While seemingly less critical than masks, gowns were worn nearly the same amount by HCWs as masks.[16]

Gloves

[edit]Medical gloves, like masks and gowns, also serve the purpose of preventing contamination of disease by blocking contact between the hands and the various bacteria, fluid, and fomites that carry the disease.[23] HCWs can again, like gowns, easily dispose of and change gloves in order to help improve and maintain good sanitary conditions.[24] Compared to all of the other pieces of equipment, gloves were worn the most often by HCWs who contracted the disease.[16]

Eye protection

[edit]HCWs used and continue to use a variety of eye protection, like personal and safety glasses, goggles, and face shields, but most relied on face shields and goggles when dealing with SARS patients.[25] In general, eye protection is most helpful in blocking any harmful particles (in this case bacteria or fluid from a patient) from entering the eye of a HCW. One distinction between eye protection and the other types of equipment, however, is that eye protection is often reusable. This characteristic of eye protection therefore makes understanding the methods used to clean the eye protection equipment a factor when assessing the success of using eye protection to prevent disease transmission.[10] These include how often the equipment is cleaned, what is used to clean the equipment, and the location of where the equipment is being cleaned.[10] While nearly all HCWs that contracted the disease reported that they wore some form of eye protection, many of them inadequately washed their eye equipment and did so in a SARS unit.[10]

Psychological effects

[edit]During outbreaks like the SARS outbreak in 2002-2003, HCWs are put under significantly greater amounts of stress and pressure to help cure patients and relieve them of disease.[26] Because there was no known cure for SARS, the pressure and stress was especially prominent among HCWs.[27] With this challenge came many psychological effects—most notably stress.

Stress was a psychological effect experienced by many HCWs during the outbreak.[26] This stress resulted from the fatigue and pressure of having to work longer hours and shifts in attempt to improve the treatment and the containment of the disease.[10] Meanwhile, many HCWs refrained from returning home in between shifts to avoid the possibility of transmitting the disease to family members or others in the community, which only exacerbated the emotional and physical stress and fatigue that the HCWs experienced.[10] Even more, the occupational stress of the HCWs only grew by dealing with sick and often dying patients. This stress has the capability to ease the transmission of the disease, which is a large reason for it being a cause of the disease in HCWs.[10] This is because, as HCWs become more stressed and tired, they compromise the strength of their immune system.[28] As a result, HCWs are more prone to actually getting the disease when they encounter certain causes of transmission, like the high-risk performance causes above.[28]

Lack of information

[edit]Lack of information about SARS

[edit]The outbreak of SARS involved significant amounts of uncertainty, as the specifics of the disease were unknown and treatment was not properly established at first.[29] More importantly, a cure did not (and still does not) exist, and HCWs and others involved originally knew little about how the disease was transmitted and from where it originated.[29] Due to this lack of information, partially coming from the Chinese government's unwillingness to share information on its patients, doctors were not quick to notice and diagnose the disease in its earliest stages, as they were still unsure about the disease's characteristics and origins.[30] These factors collectively allowed the disease to spread much quicker at first, infecting HCWs who knew little about the method of transmission of the disease. They were therefore unable to adequately protect themselves from the disease, and communication surrounding disease treatment and prevention was inhibited by their lack of knowledge.[29]

Inadequate training for HCWs

[edit]In addition to the POC's release of its set of SARS-specific directives in 2003, there was also training that was to be completed by HCWs planning to deal with and care for SARS patients.[10] This training included video sessions and other lessons equipping HCWs for safe interactions with SARS patients. Unfortunately, not all of this training was done—if at all—before HCWs began to interact with SARS patients.[25] Over a third of HCWs never received any type of formal training, and half of those receiving any formal training received it after they had begun to interact with and care for SARS patients.[10] At the same time, many of the HCWs receiving training received it from another HCW, allowing for the possibility of some error in the training.[10] Aside from this type of training, many HCWs complained that most efforts—which included only posting informational posters in the wards—were inadequate.[10]

Prevention and treatment in the future

[edit]After the large outbreak of SARS in 2002-2003, many doctors and organizations, such as the CDC, published a new set of recommendations and guidelines on preventing and dealing with possible outbreaks or cases of SARS in the future.[31] They “revised the draft based on comments received from public health partners, healthcare providers, and others” in November 2003 in order to improve prevention and treatment success throughout the world.[32] The document is comprised of several sections, which include guidelines targeted specifically towards HCWs (e.g. “Preparedness and Response in Healthcare Facilities”) and other proactive measures directed towards whole communities (e.g. “Communication and Education” and “Managing International Travel-Related Transmission Risk”).[32] Furthermore, each section includes a subsection called “Lessons Learned,” where the CDC explains issues and failures in the topic during the past outbreak so that HCWs and others recognize mistakes and do not make them again.[32] The hope is that HCWs will be able to better prevent the transmission of the disease among themselves but also among others by now having the knowledge and guidelines needed to avoid all of the threats and causes explained above that enabled the transmission of the disease among HCWs from 2002-2003.[32]

Treatment

[edit]There is still no vaccine or cure for SARS, and ntibiotics are ineffective for treating SARS because the disease is viral. As a result, the quarantine of infected patients is critical to prevent transmission, and using barrier nursing policies is also important to monitor patients in a safe and sanitary way.[33] Fortunately, various governments, health-focused non-profits, and research groups have been working with the CDC and other organizations to try and successfully find a cure for the disease.[34]

Prevention

[edit]Because there is no effective cure for SARS yet, types of prevention, including sanitary and cautionary methods (e.g. hand-washing and wearing a surgical mask) remain some of the best ways to prevent the spread of the disease. Even more, lessons learned from the 2002-2003 outbreak point out that greater knowledge about the disease and its methods of transmission, better and more effective training for HCWs, and potential stress-reducers for HCWs dealing with SARS patients, will all help prevent the disease from being transmitted to HCWs and others in the future.[10]

Further reading and external links

[edit]- Severe acute respiratory syndrome: Wikipedia's article on SARS for further information on the symptoms, diagnosis, treatments, history, etc. of SARS in general.

- SARS: CDC's main webpage on SARS, including information about the disease, guidelines for treatment and prevention, groups with risk for the disease, etc.

- SARS: LESSONS FROM TORONTO Information on the chronology of the SARS outbreak in Toronto regarding average citizens and HCWs.

- Cluster of Cases of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Among Toronto Healthcare Workers After Implementation of Infection Control Precautions: A Case Series Full Study referenced in article regarding causes of SARS in Toronto HCWs.

- Public Health Guidance for Community-Level Preparedness and Response to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) CDC's set of recommendations and guidelines on preventing and dealing with SARS in future that is referenced earlier in the article.

- Transmission (medicine): Wikipedia article that provides more extensive detail on the methods of disease transmission in general; includes but is not limited to information applying to SARS transmission.

- SARS News and Alerts Archive: provides relevant news articles and updates published from 2003-2004 regarding SARS cases that popped up in that time.

References

[edit]- ^ Fong, Kevin (2013-08-16). "They risked their lives to stop Sars". BBC News. Retrieved 2017-10-24.

- ^ Chan-Yeung, Moira; Yu, W. C. (2003). "Outbreak Of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome In Hong Kong Special Administrative Region: Case Report". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 326 (7394): 850–852. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7394.850. JSTOR 25454235. PMC 153470. PMID 12702616.

- ^ Ofner‐Agostini, Marianna; Gravel, Denise; McDonald, L. Clifford; Lem, Marcus; Sarwal, Shelley; McGeer, Allison; Green, Karen; Vearncombe, Mary; Roth, Virginia; Paton, Shirley; Loeb, Mark; Simor, Andrew (2006). "Cluster of Cases of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Among Toronto Healthcare Workers After Implementation of Infection Control Precautions: A Case Series" (PDF). Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 27 (5): 473–478. doi:10.1086/504363. JSTOR 10.1086/504363. PMID 16671028. S2CID 10618392.

- ^ Maunder, Robert (2004). "The Experience of the 2003 SARS Outbreak as a Traumatic Stress among Frontline Healthcare Workers in Toronto: Lessons Learned". Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences. 359 (1447): 1117–1125. doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1483. JSTOR 4142245. PMC 1693388. PMID 15306398.

- ^ Chan-Yeung, Moira; Yu, W. C. (2003). "Outbreak Of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome In Hong Kong Special Administrative Region: Case Report". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 326 (7394): 850–852. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7394.850. JSTOR 25454235. PMC 153470. PMID 12702616.

- ^ Maunder, Robert (2004). "The Experience of the 2003 SARS Outbreak as a Traumatic Stress among Frontline Healthcare Workers in Toronto: Lessons Learned". Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences. 359 (1447): 1117–1125. doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1483. JSTOR 4142245. PMC 1693388. PMID 15306398.

- ^ Ofner‐Agostini, Marianna; Gravel, Denise; McDonald, L. Clifford; Lem, Marcus; Sarwal, Shelley; McGeer, Allison; Green, Karen; Vearncombe, Mary; Roth, Virginia; Paton, Shirley; Loeb, Mark; Simor, Andrew (2006). "Cluster of Cases of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Among Toronto Healthcare Workers After Implementation of Infection Control Precautions: A Case Series" (PDF). Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 27 (5): 473–478. doi:10.1086/504363. JSTOR 10.1086/504363. PMID 16671028. S2CID 10618392.

- ^ "Glove Use Information Leaflet" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ Health, Center for Devices and Radiological. "Personal Protective Equipment for Infection Control - Medical Gloves". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Ofner‐Agostini, Marianna; Gravel, Denise; McDonald, L. Clifford; Lem, Marcus; Sarwal, Shelley; McGeer, Allison; Green, Karen; Vearncombe, Mary; Roth, Virginia; Paton, Shirley; Loeb, Mark; Simor, Andrew (2006). "Cluster of Cases of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Among Toronto Healthcare Workers After Implementation of Infection Control Precautions: A Case Series" (PDF). Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 27 (5): 473–478. doi:10.1086/504363. JSTOR 10.1086/504363. PMID 16671028. S2CID 10618392.

- ^ Smith, Richard D. (December 2006). "Responding to global infectious disease outbreaks: lessons from SARS on the role of risk perception, communication and management". Social Science & Medicine (1982). 63 (12): 3113–3123. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.004. ISSN 0277-9536. PMC 7130909. PMID 16978751.

- ^ Chan-Yeung, Moira; Yu, W. C. (2003). "Outbreak Of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome In Hong Kong Special Administrative Region: Case Report". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 326 (7394): 850–852. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7394.850. JSTOR 25454235. PMC 153470. PMID 12702616.

- ^ "Update: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome --- Toronto, Canada, 2003". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- ^ a b Canada, Public Health Agency of. "Canada Communicable Disease Report - Canada.ca". www.canada.ca. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- ^ a b c "Is Canada ready for MERS? 3 lessons learned from SARS". CBC News. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Ofner‐Agostini, Marianna; Gravel, Denise; McDonald, L. Clifford; Lem, Marcus; Sarwal, Shelley; McGeer, Allison; Green, Karen; Vearncombe, Mary; Roth, Virginia; Paton, Shirley; Loeb, Mark; Simor, Andrew (2006). "Cluster of Cases of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Among Toronto Healthcare Workers After Implementation of Infection Control Precautions: A Case Series" (PDF). Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 27 (5): 473–478. doi:10.1086/504363. JSTOR 10.1086/504363. PMID 16671028. S2CID 10618392.

- ^ a b c d e f "Direct and Indirect Disease Transmission" (PDF). Delaware Health and Social Services, Division of Public Health. 06/2011. Retrieved 12/13/2017.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=and|date=(help) - ^ "Definition of FOMITE". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- ^ "SARS | Frequently Asked Questions | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- ^ "Unmasking the Surgical Mask: Does It Really Work?". 2009-10-05. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- ^ J., Carter, Pamela (2008). Lippincott's textbook for nursing assistants : a humanistic approach to caregiving (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781766852. OCLC 85885386.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Simple techniques slash hospital infections: meeting". Reuters. Sat Mar 21 19:17:18 UTC 2009. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Glove Use Information Leaflet" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2009. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- ^ Health, Center for Devices and Radiological. "Personal Protective Equipment for Infection Control - Medical Gloves". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- ^ a b Canada, Public Health Agency of. "Canada Communicable Disease Report - Canada.ca". www.canada.ca. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- ^ a b Maunder, Robert G.; Lancee, William J.; Balderson, Kenneth E.; Bennett, Jocelyn P.; Borgundvaag, Bjug; Evans, Susan; Fernandes, Christopher M.B.; Goldbloom, David S.; Gupta, Mona (December 2006). "Long-term Psychological and Occupational Effects of Providing Hospital Healthcare during SARS Outbreak". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (12): 1924–1932. doi:10.3201/eid1212.060584. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 3291360. PMID 17326946.

- ^ "SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome)". nhs.uk. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- ^ a b "How Sleep Loss Affects Immunity". WebMD. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- ^ a b c "Is Canada ready for MERS? 3 lessons learned from SARS". CBC News. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- ^ "CNN.com - WHO targets SARS 'super spreaders' - Apr. 6, 2003". CNN. 2006-03-07. Archived from the original on 2006-03-07. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- ^ Srinivasan, Arjun; McDonald, Lawrence C.; Jernigan, Daniel; Helfand, Rita; Ginsheimer, Kathleen; Jernigan, John; Chiarello, Linda; Chinn, Raymond; Parashar, Umesh; Anderson, Larry; Cardo, Denise; Team, Sars Healthcare Preparedness Response Plan (2004). "Foundations of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Preparedness and Response Plan for Healthcare Facilities" (PDF). Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 25 (12): 1020–1025. doi:10.1086/502338. JSTOR 10.1086/502338. PMID 15636287. S2CID 43063142.

- ^ a b c d "SARS | Guidance | Preparedness and Response | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-11-14.

- ^ "SARS | Community Containment, Including Quarantine | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

- ^ Greenough, Thomas C.; Babcock, Gregory J.; Roberts, Anjeanette; Hernandez, Hector J.; Thomas, William D.; Jr.; Coccia, Jennifer A.; Graziano, Robert F.; Srinivasan, Mohan (2005-02-15). "Development and Characterization of a Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome–Associated Coronavirus–Neutralizing Human Monoclonal Antibody That Provides Effective Immunoprophylaxis in Mice". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 191 (4): 507–514. doi:10.1086/427242. ISSN 0022-1899. PMC 7110081. PMID 15655773.