User:Amir Ghandi/Tahmasp I

| Tahmasp I | |

|---|---|

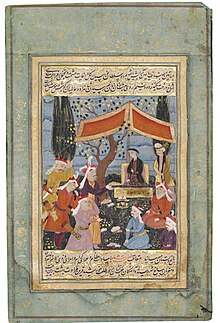

Tahmasp I in the mountains (detail), by Farrukh Beg | |

| Shah of Iran | |

| Reign | 23 May 1524 – 25 May 1576 |

| Coronation | 2 June 1524 |

| Predecessor | Ismail I |

| Successor | Ismail II |

| Regent | See list

|

| Born | 22 February 1514 Shahabad, Isfahan, Iran |

| Died | 25 May 1576 (aged 62) Qazvin, Iran, Safavid Empire |

| Spouse | Many, among them:Sultanum Begum, Sultan-Agha Khanum |

| Issue | See below |

| Dynasty | Safavid |

| Father | Ismail I |

| Mother | Tajlu Khanum |

| Religion | Twelver Shia Islam |

| seal |  |

Tahmasp I (Persian: تهماسب یکم, romanized: Ṭahmāsp; 22 February 1514 – 14 May 1576) was the second Shah of Safavid Iran from 1524 to 1576. the eldest son of Ismail I with his principal consort, Tajlu Khanum.

Ascendedt the throne after the death of his father on 23 May 1524, the first years of Tahmasp's reign were the stage of civil wars between the Qizilbash leaders until 1532 when he assured his authority and begun an absolute monarchy. he soon faced a longstanding war with the Ottoman Empire which lasted in three phases. the Ottomans under the command of Suleiman the Magnificent tried to put their favoured candidates on the Safavid throne. the war ended with the Peace of Amasya with Ottomans giving sovereignty over Baghdad, much of Kurdistan and western Georgia. Tahmasp also had conflicts with the Uzbeks over Khorasan with they constantly raiding Herat. he led an army in 1528 when he was fourteen and defeated the Uzbeks in the Battle of Jam, for superiority he used the artilirary which was unknown for the other side. Tahmasp led four campaigns to Georgia, conquering most of it, however, in terms of the Peace of Amasya, he could only have sovereignty over eastern parts.

Tahmasp was a patron of arts, building a royal house of arts for painters, calligraphers and poets, along with having a hand in painting as well. though later in his reign he became despise of poets and shunned many of them making them to leave Iran for India and the Mughal court. he is remarked for his religious bigotry, giving power to the clergy by allowing them to have counsul in the legal and administrate matters. an example of his fanaticism was when he demanded the fugitive Mughal emperor, Humayun, to convert to Shi'ism to be granted with military assistance for reclaiming his throne in India. in times however, Tahmasp could be a great diplomate, as he negotiated alliences with Republic of Venice and Habsburg Monarchy

Background

[edit]Tahmasp was the second Shah of the Safavid dynasty, a family of Kurdish origin[1] who were the sheikhs of a Sufi tariqa called the Safavid order centered in Ardabil.[2] the first sheikh of the order, Safi-ad-din Ardabili, whose name is eponymous of the dynasty, married the daughter of Zahed Gilani and succeeded the mastership of his father-in-law's order, the Zahediyeh.[3] two of his descendants, Shaykh Junayd and Shaykh Haydar, turned the order to a more militant nature and tried to expend their lands but failed.[2]

Eventually, it was Tahmasp's father, Ismail I who in 1502 became the Shah of Iran and by 1512 conquered the realm of Aq Qoyunlu tribal confederation, Shaybanids lands in eastern Iran, and the many city-states.[4] Ismail unlike his ancestors, believed in the Twelver Shia Islam as he announced this particular branch as the official faith of the realm.[5] he forced conversion to the Sunni population by abolishing Sunni Sufi orders, seizing their property, and giving Sunni ulama a choice of conversion, death, or exile.[6] from this, a power vacuum emerged that gave the Shia ulama a chance to create a clerical aristocracy filled with seyyid and mujtahid landowners.[7]

Ismail also marked the Qizilbash tribes as an inseparable member of the Safavid administration. as they were the “men of the sword” that brought him to power.[4][8] these "men of the sword" would constantly get into conflict with the "men of the pen" who controlled the ranks of bureaucracy and mostly were Persian. Ismail to solve this dispute, created a title called wakil-e nafs-e nafs-e homayoun, which simply played the role of a deputy to the king.[4] clashes between the Qizilbash leaders and Persian bureaucrats manifested in the Battle of Ghazdewan between Najm-e Sani the wakil of Ismail and the Uzbeks. the Uzbek victory in this battle, during which Najm was executed, was a result of Qizilbash forces leaving the wakil on his own.[9]

However, it was the Battle of Chaldiran that truly damaged Ismail's prestige and authority. before the war with Ottoman empire, Ismail promoted a holy image of himself as a reincarnation of Ali or Husayn.[10] but after Chaldiran, this belief weakened and Ismail lost his theological-religious relationship with the Qizilbash tribes as they saw him as an invincible figure, but now were disappointed.[11] this heavily impacted Ismail as he gradually fell into heavy drinking of alcohol and never again took the lead of his army, hence gave a much more space for an overwhelming power seizing by the Qizilbash tribes which also overshadowed the early reign of Tahmasp.[12]

Early life

[edit]Born on Wednesday 22 February 1514 at Shahabad, a village near Isfahan, Tahmasp was the eldest son of Ismail I and his principal consort, Tajlu Khanum.[13] refering to as Tahmasp Mirza, in 1515, he was appointed as the governor of Khorasan following the Turco-Mongol tradition.[14] the year after, Amir Soltan Mawslu, the governor of Diyarbakır, became his lala and governor of Balkh.[15] appointing Amir Soltan was an order by Ismail to replace the Shamlu and Mawslu governors of Khorasan, who during the Battle of Chaldiran for the fear of famine, did not join his army.[16] Moreover placing Tahmasp in Herat was to reduce the rising influence of the Shamlu tribe which had dominated Safavid court politics and held a number of powerful governorships.[13] Ismail also placed a religious tutor for the heir, a notable and prominent figure of Herat, Amir Ghiath al-Din Mohammad.[13]

Soon there emerged a power struggle between the two tutors in controling Herat. Amir Soltan could managed to arrest Ghiath al-Din and execute him the following day but in 1521, he was ousted from his position due to the sudden raid by the Uzbeks who crossed Amu Darya and seized parts of the city.[17] Ismail appointed Div Sultan Rumlu as the lala for Tahmasp Mirza while the governorship was given to his younger son, Sam Mirza.[13]

On the spring of 1525, Ismail fell ill on a hunting trip to Georgia, though he recovered in Ardabil on his way back to the capital.[18] however he catched a violent fever that led to his death on 23 May 1524 at Tabriz.[19]

Regency

[edit]

With the death of his father, a ten-year-old Tahmasp ascended the throne under the guardianship of his lala, Div Sultan Rumlu, who now was the de facto ruler of the realm.[13] to face that a member of Rumlu tribe dominates the power was not acceptable for the other Turkoman tribes of the Qizilbash, especially for the Ostajlu and Takkalu.[20] Kopek Sultan, governor of Tabriz and leader of Ostajlu with Chuha Sultan, leader of Takkalu tribe were Rumlu's most firm opponents.[20] the Takkalu were powerful in Isfahan and Hamadan while the Ostajlu held Khorasan and the capital Tabriz.[13] Rumlu proposed a triumvirate to the two leaders which was accepted, the terms were in sharing the office of amir al-umara (commander-in-chief).[13] however this triarchy could not live long as all the sides were unsatisfied by their share of power. thus from the spring of 1526, a series of battles on the northwest Iran started that expanded to all of Khorasan and soon became a civil war.[21] Ostajlu faction quickly were excluded with their leader, Kopek Sultan killed by the orders of Chuha Sultan.[22] parallel by the civil war in the realm, the Uzbek raiders temporarily seized Tus and Astarabad. the fault of the raids were left upon Rumlu that led to his execution.[13] Tahmasp himself performed the execution by shooting an arrow to him.[20]

On the behest of the young king, the sole remaining member of the triarchy, Chuha Sultan, became the de facto ruler of the realm for a period between 1527 to 1531.[22] Chuha would try to seize Herat from the Shamlu dominance, this led to another conflict in which the governor of Herat, Hossein Khan, raid to the loyal camp, killed Chuha and replaced him.[20] while the civil war was ongoing between the Qizilbash, Uzbeks under the command Ubayd Allah Khan took advantage and conquered the borderlands.[14] in 1528, Ubayd reconquered Astarabad and Tus alongside with besieging Herat. the fourteen-year-old Tahmasp personaly took command of an army and defeat the Uzbeks, distinguished himself bravely at the battle of Jam.[13] Safavid's superiority on this battle was more or less for their use of artillery which they learnt from Ottomans.[23] however the victory did not ease off neither the threat of Uzbeks nor the internal chaos of the realm as Tahmasp after the battle immediately returned to the west to suppress a rebelion at Baghdad.[24] in the same year, Uzbeks managed to capture Herat however they let Sam Mirza to safely return to Tabriz, though their seizure did not last long as Tahmasp on Summer 1530 drove them out. he appointed his brother Bahram Mirza as the governor of Khorasan and Ghazi Khan Takkalu as Bahram's tutor.[25]

Later In 1533, Hossein Khan was overthrown from his position and executed, even though he was by marriage related to the Shah.[20] his fall was a turning point for Tahmasp, as he now knew that each of these Turkoman leaders will have favour towards their own tribe, having this in mind, he lessend the influence of the Qizilbash and gave the "men of the pen" side of the bureaucracy a greater power thus putting an end to the Regency.[14][26]

Reign

[edit]War with Ottomans

[edit]

Suleiman the Magnificent, was the sultan of Ottoman Empire in Tahmasp's time. he could be under impression that a strong Safavid empire could grow as a threat, however during the first decade of Tahmasp reign, he was preoccupired with war with Habsburgs and siege of Vienna thus making no action.[27] in 1532, Suleiman sent Olama Beg Takkalu with 50,000 troops under the command of Fil Pasha.[13] Olama Beg was one of many Takkalu members who after the death of Chuha, took refuge to the Ottoman Empire.[28] the Ottomans were able to seize Tabriz, Kurdistan and tried to attract the support of Gilan.[29] Tahmasp managed to drive the Ottomans out but the news of yet another invasion from the Uzbeks, prevented him to truly defeat them.[13] later on july 1534, Suleiman sent his grand vizier, Ibrahim Pasha to occupy Tabriz and joined him two months later.[27] Suleiman was able to peacefully conquer Baghdad, same for the Shia cities such as Najaf.[29] Whilst the Ottomans were on their march, Tahmasp was in Balkh, in campaign against the Uzbeks.[13] the first Ottoman invasion could be called as the greatest crisis during his reign;[30] as there was an attempt of poisoning him by the Shamlu tribe, but the plan failed and as a result, the Shamlu revolted against Tahmasp who recently with removing Hossein Khan, asserted his authority.[31] the rebels contacted Suleiman and proposed him to help them enthrone Sam Mirza and in return, the Prince shall follow a pro-Ottoman policy.[13] Suleiman in fact recognized as the ruler of Iran which caused a panic in the court of Tahmasp.[30] nevertheless Tahmasp managed to reconquest the taken lands when Suleiman went to Mesopotamia, the latter tried to led another campaign against Tahamsp but with the former's skirmishing methodes in which he would mostly attack rearguards, Suleiman found no choice but to retreat to Istanbul at the end of 1535 having lost all of his gainings except Baghdad.[31]

The relation with Ottomans remained hostile until the revolt of the younger brother of Tahmasp, Alqas Mirza, who led the Safavid army during the Ottoman invasion of 1534-35 and was the governor of Shirvan.[32] he led a revolt against Tahmasp which was unsuccessful as the king was able to conquer Derbant on spring 1547 and appointed his son, Ismail as the governor.[33] Alqas fled to Crimea with his remainig forces and from there took refuge to Suleiman, promised him to restore the Sunnism in Iran and encoureged him to lead another campaign against Tahmasp.[34][35] the new invasion sought the quick capture of Tabriz on July 1548, however, it soon became clear that Alqas Mirza's claims on having the support of all the Qizilbash leaders were not true, thus made the campaign lengthy and more focusing on plundring as they plundered Hamadan, Qom and Kashan but were stopped at Isfahan.[13] Tahmasp on the other hand, followed a tactic to not concern himself with batling the outmarched Ottoman army, he laid waste the entire region from Tabriz to the frontier thus left the Ottomans unable to permanently occupy the captured lands and were soon ran out of supplies.[14] shortly Alqas Mirza was captured by on the battlefield and imprisoned in a fortress were he died later. Suleiman withdrew his campaign and by the autumn 1549, the remaining Ottoman forces retreaded.[36] Suleiman launched his last campaign against Safavids on may 1554, when Ismail, son of Tahmasp, invaded eastern Anatolia and defeated Iskandar Pasha, governor of Erzerum. he marched from Diyarbakır towards Armenian part of Karabakh and was able to reconquest all of the lost lands.[37] Tahmasp on the other hand divided his army into four army corps send each in a different direction, indicates a significant increase in the strength of the Safavid army. with the Safavids holding the superiority Suleiman had to retreate because of the affectiveness of Tahmasp's army.[38] these methodes pushed the Ottomans into the peace negotiations which resulted to Peace of Amasya in which for the Iranian part, Tahmasp recognized the sovereignty of Ottomans over Mesopotamia and much of Kurdistan, he also out of deference for Sunni Islam, banned the official holding of Omar Koshan and cursing of Rashidun caliphs. for their part, the Ottomans guaranteed Iranian pilgrims free passage to Mecca, Medina, Karbala, and Najaf.[29][39] these terms, in circumstances favourable to the Safavids are a clear evidence of a decisive victory by Tahmasp.[14]

The Matter of Georgia

[edit]

Tahmasp had an interest towards the Caucasus and especially Georgia for two reasons, one that to reduce the influence of the Ostajlu tribe who kept their lands in southern Georgia and Armenia even after the civil war in 1526 and another that a desire of booty, same as his father, however as the Georgians were mostly Christians, to justify the action, he invaded under the name of Jihad.[40] Between 1540 to 1553, Tahmasp led four campaigns against the many kings of the divided state.[41] in the first campaign, by the orders of the Shah, the Safavid army sacked Tbilisi and took a large amount of booty, which included the Churches, the wives, daughters, and sons of the nobility.[42] in his second invasion which was an excuse from Alqas Mirza's revolt to ensure that the Georgian lands are stabilised, he looted the farmlands and had Levan of Kakheti sworn fealty to him.[43] besides of plundring, Tahmasp also brought an amount of prisoners. the desandent of these prisoners later formed a "third force" on the Safavid administration and bureaucracy alongside with the Turkomans and the Persians.[42] the "third force" came to a state of power during the reign of Abbas the Great but even before him in the second quarter of Tahmasp's reign they were already recruiting to the army, getting the dominance over the position of gholam at first and then qurchi which got a much more influential role during the apex of the Safavid empire.[44]

In 1555 after the war with Ottomans, by the terms of Peace of Amasya, eastern Georgia remained in Iranian hands while western Georgia ended up in Turkish hands.[45] under these new circumstances, Tahmasp sought to established the dominance of Persian social and political institutions and by imposing numerous Iranian political and social institutions and placing converts to Islam on the thrones of Kartli and Kakheti, one of them being Davud Khan brother of Simon I of Kartli.[42] appointing Davud Khan however, did not resolved the firm resistance of the Georgian forces who attempted to reconquest Tbilisi under the command of Simon and his father Luarsab I of Kartli in the Battle of Garisi which resulted to a stalemate with Luarsab and the Safavid commander, Shahverdi Sultan slain.[46]

Royal refugees

[edit]

One of the most celebrated events of Tahmsp's reign was the visit of Humayun, the firstborn of Babur and emperor of Mughal empire, which at his accession to the throne, faced a great deal of rebelions by his brothers to claiming his rule.[47] in 1544, Humayun fled to Herat and by the royal decree journeyed through Mashhad, Nishapur, Sabzevar and Qazvin and met Tahmasp at Soltaniyeh.[48] Tahmasp honoured Homayun not as a refuge but a guest and had the kettledrums to be beaten for three days at the royal residence and gifted him an illustrated version of Saadi's Gulistan dated back to Abu Sa'id Mirza's reign, the Mughal emperor's great-grandfather.[49][50] however the Shah refused to give any political assistance to him unless he convert to Shi'ism. Humayun reluctantly, accepted the faith but in return to India reversed to Sunni Islam albeit he had an open religious policy thus did not forced any of Iranian Shias to convert.[47] Tahmasp also demanded a quid pro quo in which the important city of Kandahar be given to his infant son Morad Mirza.[48][51] Humayun spent the Nowruz in the Shah's court and in 1545 by an army provided by Tahmasp went to regain his lost lands. he firstly conquered Kandahar and ceded it to the young Safavid prince.[52] however Morad Mirza soon died and the city became a contention zone between the two empires, Safavid claiming that the territory had been given to them in perpetuity and the Mughals claiming that the apanage had reverted to them upon the death of the prince.[48] Tahamsp started the first expedition to Kandahar in 1558, reconquering the city.[30]

Another notable refuge to Tahmasp's court was Şehzade Bayezid, the fugitive Ottoman prince who rebelled against his father, Suleiman the Magnificent and with an army of 10000 fully armed men went to the Safavid Shah to persude him to start a war against the Ottomans.[53] Tahmasp though honoured Bayezid greatly, did not desired to disturb the newly signed Peace with Ottomans and as Suleiman made clear that he would reconfirm the Peace of Amysia, he was urged to hand over Bayezid and his children to Suleiman.[54][55] Tahmasp suspected that Bayezid is planing a coup thus using this excuse, he arrested and sent him to Ottomans and he alongside with his children were executed as soon as they were put into Ottoman custody.[53]

Later life and death

[edit]

It has been suggested that soon after the Peace of Amasya in 1555, Tahmasp scarcely left Qazvin until his death in 1576, in fact he was continually active over this period in the face of a variety of internal and external challenges. in 1564 he faced a rebelion in Herat which was put down by Masum Bek and Khorasan governors, however the region still was troublesome as it faced raids by the Uzbeks in 1566.[56] in 1574, he fell heavly ill, an illness lasting two month with twice coming to the point of death.[53] as he did not have chosen a crown prince, the question of succession occured between the members of the royal family and the leaders of Qizilbash, in which should the state pass down to his favourite son, Haydar Mirza, supported by the Ustajlu tribe and the powerful Georgians of the court or the imprisoned prince, Ismail Mirza, supported by Pari Khan Khanum, Tahmasp's influentioal daughter.[57] the pro-Haydar faction tried to eliminate Ismail by trying to win the favour of the castellan of Qahqaheh Castle where Ismail was imprisoned, however, Pari Khan got wind of the plot and informed Tahmasp. the Shah still holding an affection for his son ordered to the prince be guarded by Afshar musketeers.[58]

Tahmasp was able recoverd from the illness and devoted his attention as before to affairs of state. nonetheless the tention of the court remaind and trigged off another civil war when the Shah died on 14 May 1576 as a result of poison.[59] the fault of poisoning was left upon a physician called Abu Naser Gilani who attended the Shah when he fell ill however according to Tarikh-e Alam-ara-ye Abbasi: "he unwisely sought recognition of his superior status visà-vis the other physicians; as a result, when Tahmasp died, Abu Nasr was accused of treachery in the treatment he had prescribed, and he was put to death within the palace by members of the qurchi"[14]

Tahmasp I had the longest reign of any member of the Safavid dynasty as when he died on 14 May 1576 his reign was only nine days shorter than fifty-two years.[14]

Policies

[edit]Administration

[edit]

Tahmasp's reign after the aforementioned civil wars between the Qizilbash leaders, turned to a "personal rule" which sought to control the Turkoman influence by empowering the Persian part of bureaucracy, the key change was appointing Qazi Jahan Qazvini in 1535 who brought a diplomatic range beyond Iranian theater, beginning of rhetorical dialogues with the Portuguese, the Venetian, the Mughals and the Sh'ite Dynasties of the Deccan.[60] England through the explorer Anthony Jenkinson who was received at the Safavid court in 1562 sought to promote the trade as well.[14] the Habsburgs were also eager to form an alince against Ottomans with the Safavids, as in 1529 Ferdinand I sent an envoy to Iran with the objective of making an attack on the Ottoman Empire in the west and the east within the following year, however the plan did not take place as the envoy took longer than a year to return.[61] with newly foreign relations, the first extant Safavid letters to a European power was sent in 1540 to Doge of Venice, Pietro Lando parallel with arriving of Michel Membré the ambassador of Venice who wrote Relazione di Persia, one of the few European sources that describe the court of Tahmasp.[62] in the letter to the Doge which is written by Tahmasp himself perhaps out of his interest in this alliance, he promises that with the help of the Holy League, they will "cleanse the earth of [Ottoman] wickedness". though the alliance never came to fulfilment.[63]

One of the most Important events of Tahmasp's reign was the relocating the Capital which started "the Qazvin period" of Safavid history.[64] though there is not an exact date, it is certain that Tahmasp began the preparations to have the royal capital moved from Tabriz to Qazvin during a period of ethnic re-settlement in the 1540s.[13] the change from Tabriz to Qazvin is not simply a matter of the Shah moving from a city to another, but puting aside the Turco-Mongol tradition of shifting between summer and winter pasture with the herds thus carrying a nomedic lifestyle which Ismail I followed.[65] although Tahmasp and his advisors maybe had no conscious thought other than to avoid the threat to the capital from the Ottomans, the idea of a Turkoman state with a center in Tabriz was abondoned for an empire centered in Iranian Plateau.[66] moving into a city which with an ancient rout through Khorasan was linked to all the realm, allowed a greater degree of centralization as the distant provinces like Shirvan, Georgia and Gilan were brought into the Safavid fold.[67] Qazvin also had the feature of having a non-Qizilbash constituency which allowed Tahmasp to bring a new staff to his court there that were not somehow related to the Turk tribes. the city associated with orthodoxy and stable governance, soon saw a great deal of development under Tahmasp's patronage, mainly new palaces which of them Chehel Sotoun is the foremost one.[13]

Military

[edit]The military of Safavid came to a great evolution during Tahmasp's reign as within a few years both gunners (tupchiyan) and musketeers (tufangchiyan) came to a presence in the army.[68] the commander of the tupchiyan and tufangchiyan were the qollar-aghasis or Military slaves who were developed by Tahmasp from the prisoners of Caucasus origin.[69]

In lessening the Qizilbash power, he disused the two titles of amir al-umara and wakil.[14] from the reduction of the role of the Qizilbash in the governance, the title of qurchi-bashi emerged as the chief military officer of the state, formerly a subordinate to the amir al-umara.[70]

Religion

[edit]

Tahmasp described himself as a "pious Shia mystic king".[71] his religious fanaticism by far was the most interesting aspect of Tahmasp's character for historians as the extent to which his beliefs influenced the official religious policy of the Safavid state has roots in the modern originality of Persian Shiʿism.[13] up until 1533, The Qizilbash leaders following their tradition of worshiping Ismail I as the promised Mahdi, urged the young Tahmasp to continue in his father's footsteps, but in 1533, he went underwent a spiritual rebirth whereby performed an act of repentance and outlawed all irreligious behaviors.[72] Tahmasp rather rejected his father claims on being Messiah, Mahdi or God instead he became a mystic lover of Ali and a king bend to the sharia.[73] however he still enjoyed the unorthodox practice of villagers pilgrimage to his palace in Qazvin to touch his clothing.[13] he claimed that he has connections with Ali and Sufi saints such as his ancestor Safi al-Din through the world of dreams in which he would foresaw the future.[74] a clear sign of his love for the first shia Imam is in his desire to have the poets of his court write eulogies about Ali rather than him.[75]

Tahmasp looked to Twelverism as a new doctrine of kingship, one included with having the ulama in both religious and legal matters. for that he appointed Shaykh Ali al-Karaki as the deputy of the Hidden Imam.[71] this brought a new political and courtly agency in the mullahs and sayyeds and their various networks intersecting cities like Tabriz, Qazvin, Isfahan, and the recently incorporated centers of Rasht, Astarabad, and Amol in which they sought to pupolarise al-Karakis interpretations of Shiʿism across the Safavid domain.[76] during Tahmasp's time, the Persian scholars came to acceptance of Safavid sayyid heritage and gave Tahmasp the epithet of "the Husaynid".[77] Tahmasp embarked on a wide-scale urban program designed to reinvent the city of Qazvin as a centre of Shi`ite piety and orthodoxy as he expanded the Shrine of Husayn son of Ali al-Ridha, the eighth Imam.[78] Tahmasp also had an attentive policy to his ancestral Sufi order in Ardabil as he built the Janat Sarai mosque there to encourage an overflow of visitors and also to hold Sama ceremonies.[79] he ordered the widespread practice of Sufi rituals of devotion across his domains and had the Sufis and Mullahs to come to his royal palace in Qazvin and perform public acts of piety and zikr for the Eid al-Fitr to renew their vows of allegiance to Tahmasp. this in result encouraged Tahmasp's disciples to see themselves as belonging to one single community too large to be bound by tribal or other local social orders.[80] Tahmasp's reign saw the shiʿi conversion however unlike his father, he did not force other religious groups as he had a longstanding recognition and sponsorship of Christian Armenians.[81]

Arts

[edit]

Tahmasp has been denoted as the greatest Safavid patron.[82] he is namesake for one of the most celebrated illustrated manuscripts of the Shahnameh which was commissioned by his father probably around 1522 and was completed in mid 1530s.[83] in his youth, Tahmasp was inclined towards calligraphy and art, and brought masters who were without comparison in each of their own art and paid absolute patronage and attention to them.[13] Tahmasp against the society's preferences at the time, did not ban painting but tolerated painters thus led a free space for the remarkable painters of his time such as Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād.[84] he patronaged a royal painting workshop for masters, journeymen and apprentices with access to exotic materials such as ground gold and lapis lazuli. his painting house led to some of the most well known illustrated works of Nizami's Khamsa and Jami's Haft Awrang.[85] Tahmasp himself was a master in painting as he worked on Chehel Sotoun's balcony paitings.[86] Tarikh-e Alam-ara-ye Abbasi refers to Tahmasp's reign as the zenith of calligraphic and pictorial arts which is not an overstatement considering the amount of remaining works from his time.[13]

The poetry on the other hand has a debatable place on whether Tahmasp did encouraged it or had parts in its weakening.[87] according to Tazkera-ye Tohfe-ye Sāmi by Tahmasp's brother, Sam Mirza, there was 700 poets during the reigns of the first two Safavid kings, because of the Shah's sudden repentance, a fair number of them left Tahmasp's court once they had the opportunity to join the Mughal emperor, Humayun, the remainings such as Vahshi Bafqi and Mohtasham Kashani for their erotic ghazals were shunned.[13][88] the departure of the prominent poets such as Naziri Nishapuri and 'Orfi Shirazi marked the start of the dominance of Indian style or sabk-i hindi poetry, which resulted to the spread of Persian language in the literature of India, which only came to possibleness because of Tahmasp's bigotry.[87][89]

Family

[edit]| Ancestors of Amir Ghandi/Tahmasp I[4][90][91][92] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tahmasp unlike his ancestors who for allience married Turkomans, took Georgians and Circassians as wife thus of his children, mostly were of Caucasian origin.[93] Tahmasp's only Turkoman consort was his cheif wife, Sultanum Begum of Mawsillu tribe, a marriege for allience, she gave birth to two sons, Mohammad Khodabanda and Ismail II.[94] Tahmasp's fathering is consider to be caring, despite unpleasant relation with his son Ismail as he imprisoned him for his homosexuality;[33] he led an attentive role in his children's life as he had his daughters to be taught well in administrative matters, art and having the knowledge of scholars[95] and had his favourite son, Haydar Mirza, born of a Georgian slave, to participate in affairs of state.[96]

- Consorts

Tahmasp had many consorts, from them, seven are known:

- Sultanum Begum (ca. 1516; died at Qazvin, 1593), Tahmasp's cheif wife, of Mawsillu tribe, mother of his two senior sons.[97]

- Sultan-Agha Khanum, a Circassian, sister of Shamkhal Sultan Cherkes, Governor of Sakki, mother of Pari Khan Khanum and Suleiman Mirza.[98]

- Sultanzada Khanum, a Georgian slave, mother of Haydar Mirza.[93]

- Zahra Baji, a Georgian, mother of Mustafa Mirza and Ali Mirza.[99]

- Huri Khan Khanum, a Georgian, mother of Zeynab Begum and Maryam Begum.[100]

- A sister of Waraza Shalikashvili.[101]

- Zaynab Sultan Khanum (m. 1549; died at Qazvin, October 1570, buried in Mashhad), widow of Tahmasp's younger brother Bahram Mirza.[102]

- Sons

Tahmasp had thirteen sons:

- Mohammad Khodabanda (born 1532 – died 1595 or 1596), Shah of Iran (reign 1578–1587).[103]

- Ismail II (born 31 May 1537 – died 24 November 1577), Shah of (reign Iran 1576–77).[33]

- Murad Mirza (died 1545), Governor of Kandahar, died as an infant.[48]

- Suleiman Mirza (died 9 November 1576), Governor of Shiraz, killed during Ismail II's purge.[33]

- Haydar Mirza (born 28 September 1556 – died 9 November 1576), self-proclaimed Shah of Iran for a day after death of Tahmasp, killed by his guards in Qazvin.[104]

- Mustafa Mirza, (died 9 November 1576), killed during Ismaill II's purge.[33] his daughter married Abbas the Great.[105]

- Junayd Mirza (died 1577), killed during Ismaill II's purge.[14]

- Mahmud Mirza (died 7 March 1577), governor of Shirvan and Lahijan, killed during Ismaill II's purge.[33]

- Imam Qoli Mirza (died 7 March 1577), killed during Ismaill II's purge.[33]

- Ali Mirza (died 31 January 1642), blinded and imprisoned by Abbas the Great.[14]

- Ahmad Mirza (died 7 March 1577), killed during Ismaill II's purge.[33]

- Murad Mirza (died 1577), killed during Ismaill II's purge.[14]

- Zayn al-Abedin Mirza, died in childhood.[14]

- Musa Mirza, died in childhood.[14]

Daughters

Tahmasp probably had thirteen daughters which eight of them are known[14]:

- Gawhar Sultan Begum (died 1577), married to Sultan Ibrahim Mirza.[95]

- Pari Khan Khanum (died 1578), died by the orders of Khayr al-Nisa Begum.[106]

- Zeynab Begum (died 31 May 1640) married Ali-Qoli Khan Shamlu.[107]

- Maryam Begum (died 1608), married to Khan Ahmad Khan.[14]

- Shahrbanu Khanum, married to Salman Khan Ustajlu.[108]

- Khadija Begum (died after 1564), married to Jamshid Khan, grandson of Amira Dabbaj, a local ruler in western parts of Gilan.[108]

- Fatima Sultan Khanum (died 1581), married to Amir Khan Mawsillu.[14]

- Khanish Begum, married to Shah Nimtullah Amir Nizam al-Din Abd al-Baqi, leader of Ni'matullāhī order.[98]

Legacy

[edit]Tahmasp I reigned for fifty-two years, longer than any other Safavid king. in the western eyes, he made little impression for historians and what impression it did make was wholly unfavourable. he is described as a miser, a religious bigot, a man of great lust, so that he would never leave harem and he is not credited with any particular skill either in the arts of peace or of war.[68]

However it should not be forgotten that the first decade of Tahmasp's reign was similar to the after Chaldiran years of Ismail I's reign in which the latter clearly discouraged, failed to bring himself out of misery while his son was able to assert his authority and took over the power from the Qizilbash tribes. he was remarkably courageous to face Uzbeks in the age of fourteen and had a military mind to not face the Ottomans directly.[66] the fact that Tahmasp was able to maintain and expand the empire he inherited from his father during the times of revolt and strife, should be regarded to his great military leadership.[13]

Tahmasp could not be viewed as an avaricious either, it is true that he often sold jewels and dealt in other merchandise yet, he would forgo the taxes on the grounds that they offended against religious law; thereby rejecting an income of some 30,000 tomans.[109][110]

References

[edit]- ^ Amoretti & Matthee 2009.

- ^ a b Matthee 2008.

- ^ Babinger & Savory 1995.

- ^ a b c d Savory & Karamustafa 1998.

- ^ Savory & Gandjeï 2007.

- ^ Brown 2009, p. 235.

- ^ Savory et al. 2012.

- ^ Bakhash 1983.

- ^ Mazzaoui 2002.

- ^ Mitchell 2009a, p. 32.

- ^ Roemer 2008, p. 225.

- ^ Mitchell 2009b; Savory & Karamustafa 1998.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Mitchell 2009b.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Savory & Bosworth 2012.

- ^ Mitchell 2009b; Newman 2008, pp. 21.

- ^ Newman 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Mitchell 2009b; Newman 2008, pp. 21.

- ^ Roemer 2008, p. 227.

- ^ Newman 2008, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e Roemer 2008, p. 234.

- ^ Savory & Bosworth 2012; Roemer 2008, pp. 234.

- ^ a b Newman 2008, p. 26.

- ^ Roemer 2008, p. 236.

- ^ Mitchell 2009b; Savory & Bosworth 2012.

- ^ Mitchell 2009b; Roemer 2008, pp. 236.

- ^ Roemer 2008, p. 235.

- ^ a b Roemer 2008, p. 241.

- ^ Newman 2008, p. 26–27.

- ^ a b c Newman 2008, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Streusand 2019, p. 148.

- ^ a b Roemer 2008, p. 242.

- ^ Fleischer 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ghereghlou 2016a.

- ^ Roemer 2008, p. 242–243.

- ^ Mitchell 2009a, p. 79.

- ^ Roemer 2008, p. 243.

- ^ Roemer 2008, p. 243–244.

- ^ Savory 2007, p. 63.

- ^ Köhbach 1989.

- ^ Savory 2007, pp. 65; Panahi 2015, pp. 52.

- ^ Savory 2007, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Hitchins 2001.

- ^ Panahi 2015, p. 46.

- ^ Roemer 2008, p. 246.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2015, p. xxxi.

- ^ Roemer 2008, p. 245.

- ^ a b Savory 2007, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d Thackston 2004.

- ^ Eraly 2000, p. 104.

- ^ Soudavar 2017, p. 49.

- ^ Savory 2007, p. 66–67.

- ^ Thackston 2004; Streusand 2019, pp. 148.

- ^ a b c Savory 2007, p. 67.

- ^ Faroqhi & Fleet 2013, p. 446.

- ^ Mitchell 2009a, p. 126.

- ^ Newman 2008, p. 38–39.

- ^ Roemer 2008, p. 247.

- ^ Pārsādust 2009.

- ^ Roemer 2008, p. 248.

- ^ Mitchell 2009a, p. 68.

- ^ Slaby 2005.

- ^ Mitchell 2009a, p. 90.

- ^ Mitchell 2009a, p. 90–91.

- ^ Aldous 2021, p. 35.

- ^ Aldous 2021, p. 37.

- ^ a b Roemer 2008, p. 249.

- ^ Mitchell 2009a, p. 105.

- ^ a b Savory 2007, p. 57.

- ^ Streusand 2019, p. 170.

- ^ Savory 2007, p. 56.

- ^ a b Streusand 2019, p. 164.

- ^ Mitchell 2009b; Savory & Bosworth 2012.

- ^ Babayan 2012, p. 291.

- ^ Babayan 2012, p. 292.

- ^ Canby 2000, p. 72.

- ^ Mitchell 2009a, p. 109.

- ^ Newman 2008, p. 30.

- ^ Mitchell 2009a, p. 106.

- ^ Newman 2008, p. 32.

- ^ Babayan 2012, p. 295–296.

- ^ Mitchell 2009b; Mitchell 2009a, pp. 104.

- ^ Streusand 2019, p. 191.

- ^ Simpson 2009.

- ^ Soudavar 2017, p. 51.

- ^ Mitchell 2009b; Streusand 2019, p. 191.

- ^ Ghasem Zadeh 2019, p. 4.

- ^ a b Ghasem Zadeh 2019, p. 7.

- ^ Soudavar 2017, p. 50–51.

- ^ Faruqi 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Ghereghlou 2016b.

- ^ Woods 1999, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Savory 2007, pp. 18.

- ^ a b Savory 2007, p. 68.

- ^ Newman 2008, p. 29.

- ^ a b Szuppe 2003, p. 150.

- ^ Roemer 2008, p. 247; Savory 2007, p. 68.

- ^ Newman 2009, p. 29.

- ^ a b Szuppe 2003, p. 147.

- ^ Szuppe 2003, p. 153.

- ^ Szuppe 2003, p. 149.

- ^ Mitchell 2011, p. 67.

- ^ Newman 2008, p. 31.

- ^ a b Savory 2007, p. 70.

- ^ Savory 2007, p. 69.

- ^ Canby 2000, p. 118.

- ^ Savory 2007, p. 71.

- ^ Babaie et al. 2004, p. 35.

- ^ a b Szuppe 2003, p. 146.

- ^ Savory 2007, p. 60.

- ^ Roemer 2008, p. 250.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aldous, Gregory (2021). "The Qazvin Period and the Idea of the Safavids". In Melville, Charles (ed.). Safavid Persia in the Age of Empires, the Idea of Iran Vol. 10. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 29–46. ISBN 9780755633784.

- Amoretti, Biancamaria Scarcia; Matthee, Rudi (2009). "Ṣafavid Dynasty". The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. London.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Babaie, Sussan; Babayan, Kathryn; Baghdiantz-McCabe, Ina; Farhad, Massumeh (2004). "The Safavid Household Reconfigured: Concubines, Eunuchs, and Military Slaves". Slaves of the Shah: New Elites of Safavid Iran. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0857716866.

- Babayan, Kathryn (2012). "The Safavids in Iranian History (1501–1722)". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 285–306. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199732159.001.0001. ISBN 9780199732159.

- Babinger, Fr. & Savory, Roger (1995). "Ṣafī al-Dīn Ardabīlī". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09834-3.

- Bakhash, S. (1983). "ADMINISTRATION in Iran vi. Safavid, Zand, and Qajar periods". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Brown, Daniel W. (2009). A new introduction to Islam. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405158077. OCLC 1150802228.

- Canby, Sheila R. (2000). The Golden Age of Persian Art, 1501-1722. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 9780810941441. OCLC 43839386.

- Eraly, Abraham (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Mughals. New Delhi: Penguin Books. p. 101-114. ISBN 9780141001432. OCLC 470313700.

- Fleischer, C. (2011). "ALQĀS MĪRZA". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Faroqhi, Suraiya N.; Fleet, Kate (2013). The Cambridge History of Turkey, Volume 2. The Ottoman Empire as a World Power, 1453–1603. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521620949.

- Faruqi, Shamsur Rahman (2004). "A Stranger in the City: The Poetics of Sabk-e Hindi" (PDF). Shaukat. Annual of Urdu Studies. 23 (2). Columbia University Press.

- Ghereghlou, Kioumars (2016a). "ESMĀʿIL II". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ghereghlou, Kioumars (2016b). "ḤAYDAR ṢAFAVI". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ghasem Zadeh, Eftekhar (2019). "Safavid approach to art in the period of Shah Tahmasb Safavid". Afagh Journal of Humanities. 31: 1–15.

- Hitchins, Keith (2001). "GEORGIA ii. History of Iranian-Georgian Relations". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Köhbach, M. (1989). "AMASYA, PEACE OF". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Newman, Andrew J. (2008). Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–281. ISBN 9780857716613.

- Matthee, Rudi (2008). "SAFAVID DYNASTY". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mazzaoui, Michel M. (2002). "NAJM-E ṮĀNI". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mitchell, Colin P. (2009a). The Practice of Politics in Safavid Iran: Power, Religion and Rhetoric. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–304. ISBN 978-0857715883.

- Mitchell, Colin P. (2011). New Perspectives on Safavid Iran: Empire and Society. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-99194-3.

- Mitchell, Colin P (2009b). "ṬAHMĀSP I". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442241466.

- Thackston, Wheeler M. (2004). "HOMĀYUN PĀDEŠĀH". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Panahi, Abbas (2015). "Shah Tahmasb I's Military Campaigns' Consequences to Caucasus and Georgia". Historical Reaserch of Iran and Islam (in Persian). 9 (17): 47–64. doi:10.22111/JHR.2016.2536.

- Pārsādust, Manučehr (2009). "PARIḴĀN ḴĀNOM". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Roemer, H. R. (2008). "THE SAFAVID PERIOD". The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 6: The Timurid and Safavid Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 189–350. ISBN 9781139054980.

- Savory, Roger M.; Karamustafa, Ahmet T. (1998). "ESMĀʿĪL I ṢAFAWĪ". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Savory, Roger M. (2007). Iran Under the Safavids. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521042512.

- Savory, Roger M.; Gandjeï, T. (2007). "Ismāʿīl I". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Savory, Roger M.; Bosworth, C.E. (2012). "Ṭahmāsp". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Savory, Roger M.; Bruijn, J.T.P.; Newman, A.J.; Welch, A.T. (2012). "Ṣafawids". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Slaby, Helmut (2005). "AUSTRIA i. Relations with Persia". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Streusand, Douglas E. (2019) [2011]. Islamic Gunpowder Empires: Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429499586. ISBN 9780429499586.

- Simpson, Marianna Shreve (2009). "ŠĀH-NĀMA iv. Illustrations". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Soudavar, Abolala (2017) [1999]. "Between the Safavids and the Mughals: Art and Artists in Transition". Iran. 37 (1): 49–66. doi:10.2307/4299994. JSTOR 4299994.

- Szuppe, Maria (2003). "Status, knowledge, and politics : women in Sixteenth-Century Safavid Iran". In Nashat, Guity (ed.). Women in Iran from the Rise of Islam to 1800. University of Illinois Press. pp. 140–170. ISBN 9780252071218. OCLC 50960739.

- Woods, John E (1999). The Aqquyunlu : clan, confederation, empire. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0-585-12956-8. OCLC 44966081.