User:Al Ameer son/Mu'awiya

Origins and early life

[edit]Mu'awiya's year of birth is uncertain with 597, 603 or 605 cited by the Muslim traditional sources.[1] His father Abu Sufyan ibn Harb was a prominent Meccan merchant who often led trade caravans to Syria.[2] He emerged as the preeminent leader of the Banu Abd Shams clan of the Quraysh, the dominant tribe of Mecca, during the early stages of its conflict with the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[1] The latter too hailed from the Quraysh and was distantly related to Mu'awiya via their common paternal ancestor, Abd Manaf ibn Qusayy.[3][4] Mu'awiya's mother, Hind bint Utba, was also a member of the Banu Abd Shams.[1]

In 624, Muhammad and his followers attempted to intercept a Meccan caravan led by Mu'awiya's father on its return from Syria, prompting Abu Sufyan to call for reinforcements.[5] The Qurayshite relief army was routed in the ensuing Battle of Badr, in which Mu'awiya's elder brother Hanzala and their maternal grandfather, Utba ibn Rabi'a, were killed.[2] Abu Sufyan replaced the slain leader of the Meccan army, Abu Jahl, and led the Meccans to victory against the Muslims at the Battle of Uhud in 625.[1] After his abortive siege of Muhammad in Medina at the Battle of the Trench in 627, he lost his leadership position among the Quraysh.[1]

Mu'awiya and his father may have reached an understanding with Muhammad during the truce negotiations at Hudaybiyya in 628 and Mu'awiya's widowed sister, Umm Habiba, was wed to Muhammad in 629.[1] When Muhammad entered Mecca in 630, Mu'awiya, his father and his elder brother Yazid embraced Islam.[1] As part of Muhammad's efforts to reconcile with his tribesmen, Mu'awiya was made one of his kātibs (scribes), being one of seventeen literate members of the Quraysh at that time.[1] The family moved to Medina to maintain their new-found influence in the nascent Muslim community.[6]

Governorship of Syria

[edit]Early military career and administrative promotions

[edit]

After Muhammad died in 632, Abu Bakr became caliph (leader of the Muslim community). Having to contend with challenges to his leadership from the Ansar, the natives of Medina who had provided Muhammad safe haven from his erstwhile Meccan opponents, and the mass defections of several Arab tribes, Abu Bakr reached out to the Quraysh, particularly its two strongest clans, the Banu Makhzum and Banu Abd Shams, to shore up support for the Caliphate.[7] Among those Qurayshites whom he appointed to suppress the rebel Arab tribes during the Ridda wars (632–633) was Mu'awiya's brother Yazid, whom he later dispatched as one of four commanders in charge of the Muslim conquest of Byzantine Syria in c. 634.[8] The caliph appointed Mu'awiya commander of Yazid's vanguard.[1] Through these appointments Abu Bakr gave the family of Abu Sufyan a stake in the conquest of Syria, where Abu Sufyan already owned property in the vicinity of Damascus, in return for the loyalty of the Banu Abd Shams.[8]

Abu Bakr's successor Umar (r. 634–644) appointed Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah as the general commander of the Muslim army in Syria in 636 after the rout of the Byzantines at the Battle of Yarmouk,[9] which paved the way for the conquest of the remainder of Syria.[10] Mu'awiya was among the Arab troops that entered Jerusalem with Caliph Umar in 637.[1] Mu'awiya and Yazid were dispatched by Abu Ubayda to conquer the coastal towns of Sidon, Beirut and Byblos.[11] After Abu Ubayda died in the plague of Amwas in 639, Umar split the command of Syria, appointing Yazid as governor of the military districts of Damascus, Jordan and Palestine, and Iyad ibn Ghanm governor of Homs and the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia).[1][12] When Yazid succumbed to the plague later that year, Umar appointed Mu'awiya the military and fiscal governor of Damascus, and possibly Jordan as well.[1][13] In 640 or 641, Mu'awiya captured Caesarea, the district capital of Byzantine Palestine, and then captured Ascalon, completing the Muslim conquest of Palestine.[1][14][15] As early as 640/41, Mu'awiya may have led a campaign against Byzantine Cilicia and proceeded to Euchaita, deep in Byzantine territory.[16] In 644, he led a foray against Amorium in Byzantine Anatolia.[17]

Upon the accession of Caliph Uthman (r. 644–656), Mu'awiya's governorship was enlarged to include Palestine, while Umayr ibn Sa'd al-Ansari was confirmed as governor of the Homs-Jazira district.[1] In late 646 or early 647, Uthman attached the Homs-Jazira district to Mu'awiya's Syrian governorship,[1] greatly increasing the military manpower at his disposal.[18] The successive promotions of Abu Sufyan's sons contradicted Umar's efforts to curtail the influence of the Qurayshite aristocracy in the Muslim state in favor of the early Muslim converts.[12] According to the historian Leone Caetani, this exceptional treatment stemmed from Umar's personal respect of the Umayyads, the branch of the Banu Abd Shams to which Mu'awiya belonged.[13] This is doubted by the historian Wilferd Madelung, who surmises that Umar had little choice, due to the lack of a suitable alternative to Mu'awiya in Syria and the ongoing plague in the region, which precluded the deployment of commanders more preferable to Umar from Medina.[13]

Consolidation of local power

[edit]During the reign of Uthman, Mu'awiya formed an alliance with the Banu Kalb,[19] the predominant tribe in the Syrian steppe extending from the oasis of Dumat al-Jandal in the south to the approaches of Palmyra and the chief component of the Quda'a confederation present throughout Syria.[20][21][22] Medina consistently courted the Kalb, which had remained mostly neutral during the Arab–Byzantine wars, particularly after Medina's entreaties to the Byzantines' principal Arab allies, the Ghassanids, were rebuffed.[23][a] Before the advent of Islam in Syria, the Kalb and the Quda'a, long under the influence of Greco-Aramaic culture and the Monophysite church,[26][27] had served Byzantium as subordinates of its Ghassanid client kings to guard the Syrian frontier against invasions by the Sasanian Persians and the latter's Arab clients, the Lakhmids.[26] By the time the Muslims entered Syria, the Kalb and the Quda'a had accumulated significant military experience and were accustomed to hierarchical order and obedience.[27] To harness their strength and thereby secure his foothold in Syria, Mu'awiya consecrated ties to the Kalb's ruling house, the clan of Bahdal ibn Unayf, by wedding the latter's daughter Maysun in c. 650.[19][22][26][28] He also married Maysun's paternal cousin, Na'ila bint Umara, for a short period.[29][b]

Mu'awiya's reliance on the native Syrian Arab tribes was compounded by the heavy toll inflicted on the Muslim troops in Syria by the plague of Amwas,[31] which caused troop numbers to dwindle from 24,000 in 637 to 4,000 in 639.[32] Moreover, the focus of Arabian tribal migration was toward the Sasanian front in Iraq.[31] Mu'awiya oversaw a liberal recruitment policy that resulted in considerable numbers of Christian tribesmen and frontier peasants fill the ranks of his regular and auxiliary forces.[33] Indeed, the Christian Tanukhids and the mixed Muslim–Christian Banu Tayy formed part of Mu'awiya's army in northern Syria.[34][35] To help pay for his troops, Mu'awiya requested and was granted ownership by Uthman of the abundant, income-producing, Byzantine crown lands in Syria, which were previously designated by Umar as communal property for the Muslim army.[36]

Though Syria's rural, Aramaic Christian population remained largely intact,[37] the Muslim conquest had caused a mass flight of Greek Christian urbanites from Damascus, Aleppo, Latakia and Tripoli to Byzantine territory,[32] while those who remained held pro-Byzantine sympathies.[31] According to the historian J. W. Jandora, "Mu'awiya was thus confronted with a population problem".[31] In contrast to the other conquered regions of the Caliphate where new garrison cities were established to house Muslim troops and their administration, in Syria the troops settled in existing cities, including Damascus, Homs, Jerusalem, Tiberias,[32] Aleppo and Qinnasrin.[25] Mu'awiya expanded this movement to the coastal cities of Antioch, Balda, Tartus, Maraqiya and Baniyas, which were restored, repopulated and garrisoned.[31] In Tripoli the governor settled significant numbers of Jews,[31] while sending to Homs, Antioch and Baalbek Persian holdovers from the Sasanian occupation of Byzantine Syria in the early 7th century.[38] Upon Uthman's direction, Mu'awiya settled groups of the nomadic Tamim, Asad and Qays tribes to areas north of the Euphrates in the vicinity of Raqqa.[31][39]

Naval campaigns against Byzantium and conquest of Armenia

[edit]Mu'awiya initiated the Arab naval campaigns against the Byzantines in the eastern Mediterranean,[1] requisitioning the harbors of Tripoli, Beirut, Tyre, Acre, and Jaffa.[33][40] Umar had rejected Mu'awiya's request to launch a naval invasion of Cyprus, citing concerns about the Muslim forces' safety at sea, but Uthman allowed him to commence the campaign in 647, after refusing an earlier entreaty.[41] The governor's rationale was that the Byzantine-held island posed a threat to Arab positions along the Syrian coast and it could be easily neutralized.[41] The exact year of the raid is unclear with the traditional Arabic sources citing late 647/648, 648/49 or 649/50, while two Greek inscriptions in the Cypriot village of Solois citing two raids launched between 648 and 650.[41]

In the histories of the 9th-century Muslim historians al-Baladhuri and Khalifa ibn Khayyat, Mu'awiya led the raid in person accompanied by his wife Katwa bint Qaraza ibn Abd Amr of the Qurayshite Banu Nawfal alongside the commander Ubada ibn al-Samit.[41][30] Katwa died on the island and at some point Mu'awiya married her sister Fakhita.[30] In a different narrative, the raid was conducted by Mu'awiya's admiral Abd Allah ibn Qays, who landed at Salamis before occupying the island.[40] In either case, the Cypriots were forced to pay a tribute equal to that which they paid the Byzantines.[40][42] Mu'awiya established a city with a garrison and a mosque to maintain the Caliphate's influence in the island, which became a staging ground for the Arabs and the Byzantines to launch raids against each other's territories.[42] The inhabitants of Cyprus were largely left to their own devices and archaeological evidence indicates uninterrupted prosperity during this period.[43]

After two previous attempts by the Arabs to conquer Armenia, a third attempt in 650 ended with a three-year truce reached between Mu'awiya and the Byzantine envoy Procopios in Damascus.[44] In 653, Muawiya received the submission of the Armenian leader Theodore Rshtuni, which the Byzantine emperor Constans II (r. 641–668) practically conceded when he withdrew from Armenia that year.[45] In 655, Mu'awiya's lieutenant commander Habib ibn Maslama al-Fihri captured Theodosiopolis and deported Rshtuni to Syria, solidifying Arab rule over Armenia.[45]

Dominance of the eastern Mediterranean enabled Mu'awiya's naval forces to raid Crete and Rhodes in 653. From the raid on Rhodes, Mu'awiya remitted significant war spoils to Uthman.[46] In 654/55, a joint naval expedition launched from Alexandria, Egypt and the harbors of Syria routed a Byzantine fleet commanded by Constans II off the Lycian coast at the Battle of the Masts. Constans II was forced to sail to Sicily, opening the way for an ultimately unsuccessful Arab naval attack on Constantinople.[47] The Arabs were either commanded by Abd Allah ibn Abi Sarh or Mu'awiya's lieutenant Abu'l-A'war.[47]

First Fitna

[edit]Mu'awiya's domain was generally immune to the growing discontent prevailing in Medina, Egypt and Kufa against Uthman's policies in the 650s.[1] The exception was Abu Dharr al-Ghifari,[1] who had been sent to Damascus for openly condemning Uthman's enrichment of his kinsmen.[48] He criticized the lavish sums that Mu'awiya invested in building his Damascus residence, the Khadra Palace, prompting the governor to expel him.[48] Uthman's confiscation of crown lands in Iraq and his nepotism[c] drove the Quraysh and the dispossessed elites of Kufa and Egypt to oppose the caliph.[50]

Uthman sent for assistance from Mu'awiya when rebels from Egypt besieged his home in June 656.[51] Mu'awiya dispatched a relief army toward Medina, but it withdrew at Wadi al-Qura when word reached of Uthman's slaying.[51] Ali, Muhammad's cousin and brother-in-law, was recognized as caliph in Medina, but was soon after opposed by much of the Quraysh led by al-Zubayr and Talha, both prominent companions of Muhammad, and Muhammad's wife A'isha, who feared the loss of their own influence and that of their tribe under Ali.[52] The latter defeated the triumvirate near Basra at the Battle of the Camel, which ended in the deaths of al-Zubayr and Talha, both potential contenders for the caliphate, and the retirement of A'isha to Mecca.[53] With his position in Iraq, Egypt and Arabia secure, Ali turned his attention toward Mu'awiya, who, unlike the other provincial governors, had a strong and loyal power base, demanded revenge for the slaying of his kinsman Uthman and could not be easily replaced.[54][53] At this point, Mu'awiya did not yet claim the caliphate and his principal aim was to keep power in Syria.[55]

For seven months from the date of Ali's election there had been no formal relations between the caliph and the governor of Syria.[56] Following Ali's victory in Basra, Mu'awiya's position was vulnerable, his territory wedged between Ali's forces in Iraq and Egypt to the east and west, while the war with the Byzantines was ongoing in the north.[57][55] After failing to gain the defection of Egypt's governor, Qays ibn Sa'd, he resolved to end the Umayyad family's hostility to Amr ibn al-As, the conqueror and former governor of Egypt, whom they accused of involvement in Uthman's death.[58] Mu'awiya and Amr, who was widely respected by the Arab troops of Egypt, made a pact whereby the latter joined the coalition against Ali and Mu'awiya publicly agreed to install Amr as Egypt's lifetime governor should they oust Ali's appointee.[59]

Though he had the firm backing of the Kalb, to shore up the rest of his base in Syria, Mu'awiya was advised by his kinsman al-Walid ibn Uqba to secure an alliance with the Yemenite tribes of Himyar, Kinda and Hamdan, who collectively dominated the Homs garrison.[60] He employed the early Muslim commander and Kindite nobleman Shurahbil ibn Simt, widely respected in Syria, to rally the Yemenites to his side.[61] He then enlisted support from the dominant leader of Palestine, the Judhamite chief Natil ibn Qays, by allowing the latter's confiscation of the district's treasury to go unpunished.[62] The efforts bore fruit and demands for war against Ali grew throughout Mu'awiya's domain.[63] Mu'awiya handed Ali's envoy, the veteran commander and chieftain of the Bajila, Jarir ibn Abd Allah, a letter that amounted to a declaration of war against the caliph, whose legitimacy he refused to recognize.[64] Mu'awiya secured his northern frontier with Byzantium by making a truce with the emperor in 657/58, enabling the governor to focus the bulk of his troops on the impending battle with the caliph.[65]

Battle of Siffin and arbitration

[edit]The two sides met at Siffin in the first week of June 657 and engaged in days of skirmishes interrupted by a month-long truce on 19 June.[66] During the truce, Mu'awiya dispatched an embassy led by Habib ibn Maslama, who presented Ali with an ultimatum to hand over Uthman's alleged killers, abdicate and allow a shūrā to decide the caliphate.[67] Ali rebuffed Mu'awiya's envoys and on 18 July declared that the Syrians remained obstinate in their refusal to recognize his sovereignty.[68] On the following day, a week of duels between Ali's and Mu'awiya's top commanders ensued.[68] The main battle between the two armies commenced on 26 July.[69] As Ali's troops advanced toward Mu'awiya's tent, the governor ordered his elite troops forward and they bested the Iraqis before the tide turned against the Syrians the next day with the deaths of two of Mu'awiya's leading commanders, Ubayd Allah, the son of Caliph Umar, and Dhu'l-Kala Samayfa, the so-called "king of Himyar".[70] The loss of Ubayd Allah, in particular, was a blow to Mu'awiya's prestige as he had been the sole, non-Umayyad blood connection to the early caliphs to lend Mu'awiya his support at this juncture.[71]

Mu'awiya rejected suggestions from his advisers to engage Ali in a duel and definitively end hostilities.[72] The battle climaxed on the so-called "Night of Clamor" on 28 July, which saw Ali's forces take the advantage in a melée as the death toll mounted on both sides.[73][72][d] This prompted Amr ibn al-As to counsel Mu'awiya the following morning to have a number of his men tie leaves of the Qur'an on their lances in an appeal to the Iraqis to settle the conflict through consultation.[73][74][75] Though this act represented a surrender of sorts as the governor abandoned, at least temporarily, his previous insistence on settling the dispute with Ali militarily and pursuing Uthman's killers into Iraq, it had the effect of sowing discord and uncertainty in Ali's ranks.[74]

The caliph adhered to the will of the majority in his army and accepted the proposal to arbitrate.[4] Moreover, Ali agreed to Amr's demand to omit his formal title, amīr al-muʾminīn (commander of the faithful, the traditional title of a caliph), from the initial arbitration document drafted on 2 August.[75][76] According to Kennedy, the agreement forced Ali "to deal with Mu'awiya on equal terms and abandon [sic] his unchallenged right to lead the community",[77] and Madelung asserts it "handed Mu'awiya a moral victory" before inducing a "disastrous split in the ranks of Ali's men".[78] Indeed, upon Ali's return to Kufa in September 658, a large segment of his troops who had opposed the arbitration defected, inaugurating the Kharijite movement.[79] The initial agreement postponed the arbitration to a later date.[80] Information in the traditional sources about the time, place and outcome of the arbitration is contradictory, but there were likely two meetings between Mu'awiya's and Ali's respective representatives, Amr and Abu Musa al-Ash'ari, the first in Dumat al-Jandal and the last in Adhruh.[81] Ali seemingly abandoned the arbitration after the first meeting in which Abu Musa—who, unlike Amr, was not particularly attached to his principal's cause[75]—accepted the Syrian side's claim that Uthman was wrongfully killed, a verdict that Ali opposed.[82] The final meeting in Adhruh collapsed and by then Mu'awiya had emerged as a major contender for the caliphate.[83]

Claim to the caliphate and resumption of hostilities

[edit]

Following the breakdown of the arbitration talks, Amr and the Syrian delegates returned to Damascus where they greeted Mu'awiya as amīr al-muʾminīn.[84] In April/May 658, Mu'awiya received a general pledge of allegiance from the Syrians.[51] In response, Ali broke off communications with Mu'awiya, mobilized for war and invoked a curse against Mu'awiya and his close retinue as a ritual in the morning prayers.[84] Mu'awiya reciprocated in kind against Ali and his closest supporters in his own domain.[85]

In July, Mu'awiya dispatched an army under Amr to Egypt after a request for intervention from pro-Uthman mutineers in the province who were being suppressed by the governor, Caliph Abu Bakr's son and Ali's stepson Muhammad.[86] The latter's troops were defeated by Amr's forces, the provincial capital Fustat was captured and Muhammad was executed on the orders of Mu'awiya ibn Hudayj, leader of the pro-Uthman rebels.[86] The loss of Egypt was a major blow to the authority of Ali, who was bogged down battling the Kharijites in Iraq and whose grip in Basra and Iraq's eastern and southern dependencies was eroding.[51][87] Though his hand was strengthened, Mu'awiya refrained from launching a direct assault against Ali.[87] Instead, his strategy was to bribe the tribal chieftains in Ali's army to his side and harry the inhabitants along Iraq's western frontier.[87] The first raid was conducted by al-Dahhak ibn Qays al-Fihri against nomads and Muslim pilgrims in the desert west of Kufa.[88] This was followed by Nu'man ibn Bashir al-Ansari's abortive attack on Ayn al-Tamr then, in the summer of 660, Sufyan ibn Awf's successful raids against Hit and Anbar.[89]

In 659/660, Mu'awiya expanded the operations to the Hejaz (western Arabia where Mecca and Medina are situated), sending Abd Allah ibn Mas'ada al-Fazari to collect the alms tax and oaths of allegiance to Mu'awiya from the inhabitants of the Tayma oasis.[90] This initial foray was defeated by the Kufans,[90] while an attempt to extract oaths of allegiance from the Quraysh of Mecca in April 660 also failed.[91] In the summer, Mu'awiya dispatched a large army under Busr ibn Abi Artat to conquer the Hejaz and Yemen.[92] He directed Busr to intimidate Medina's inhabitants without harming them, spare the Meccans and kill anyone in Yemen who refused to pledge their allegiance.[93] Busr advanced through Medina, Mecca and Ta'if, encountering no resistance and gained their recognition of Mu'awiya.[94] In Yemen, Busr executed several notables in Najran and its vicinity on account of past criticism of Uthman or ties to Ali, massacred numerous tribesmen of the Hamdan and townspeople from Sana'a and Ma'rib.[95] Before he could continue his campaign in Hadhramawt, he withdrew upon the approach of a Kufan relief force.[96]

News of Busr's actions in Arabia spurred Ali's troops to rally behind his planned campaign against Mu'awiya,[97] but the expedition was aborted as a result of Ali's assassination by a Kharijite in January 661.[98] Afterward, Mu'awiya led his army toward Kufa where Ali's son al-Hasan had been nominated as his successor.[99] Al-Hasan abdicated in return for a financial settlement and Mu'awiya entered Kufa in July or September 661 and was recognized as caliph.[51][100] This year is considered by the traditional Muslim sources as "the year of unity" and is generally regarded as the start of Mu'awiya's caliphate.[51][100]

Before and/or after Ali's death, Mu'awiya received oaths of allegiance in one or two formal ceremonies in Jerusalem, the first in late 660/early 661 and the second in July 661.[101] The 10th-century Jerusalemite geographer al-Maqdisi holds that Mu'awiya had further developed a mosque originally built by Caliph Umar on the Temple Mount and received his formal oaths of allegiance there.[102] According to the earliest extant source about Mu'awiya's accession in Jerusalem, the near-contemporaneous Maronite Chronicles, composed by an anonymous Syriac author, Mu'awiya received the pledges of the tribal chieftains and then prayed at Golgotha and the Tomb of the Virgin Mary in Gethsemane, both adjacent to the Temple Mount.[103] The Maronite Chronicles also maintain that Mu'awiya "did not wear a crown like other kings in the world".[104]

Caliphate

[edit]Domestic rule and administration

[edit]There is little information in the Muslim traditional sources about Mu'awiya's rule in Syria, the center of his caliphate.[105][106] He established his court in Damascus and moved the caliphal treasury there from Kufa.[105] He relied on his Syrian tribal soldiery, increasing their pay at the expense of the Iraqi garrisons.[105] The highest stipends were paid on an inheritable basis to 2,000 nobles of the Quda'a and Kinda tribes, the core components of his support base, who were further awarded the privilege of consultation for all major decisions and the rights to veto or propose measures.[26][107] The respective leaders of the Quda'a and the Kinda, the Kalbite chief Ibn Bahdal and the Homs-based Shurahbil, formed part of his Syrian inner circle along with the Qurayshites Abd al-Rahman, son of the distinguished commander Khalid ibn al-Walid, and al-Dahhak ibn Qays.[108]

Mu'awiya is credited by the traditional sources for establishing dīwāns (government departments) for correspondences (rasāʾil), chancellery (khātam) and the postal route (barīd).[26] Following an assassination attempt by the Kharijite al-Burak ibn Abd Allah on Mu'awiya while he was praying in the mosque of Damascus in 661, Mu'awiya established a caliphal ḥaras (personal guard) and shurṭa (select troops) and the maqṣūra (reserved area) within mosques.[109][110] The caliph's treasury was largely dependent on the tax revenues of Syria and income from the crown lands that he confiscated in Iraq and Arabia.[26] He also received the customary fifth of the war booty acquired by his commanders during expeditions.[26] In the Jazira, Mu'awiya coped with the tribal influx, which spanned previously established groups such as the Sulaym, newcomers from the Mudar and Rabi'a confederations and civil war refugees from Kufa and Basra, by administratively detaching the military district of Qinnasrin–Jazira from Homs, according to the 8th-century historian Sayf ibn Umar.[111][112] The 9th-century historian al-Baladhuri attributes this change to Mu'awiya's successor Yazid I (r. 680–683).[111]

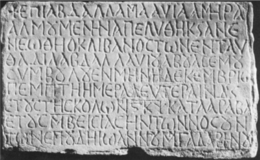

Syria retained its Byzantine-era bureaucracy, which was staffed by Christians including the head of the tax administration, Sarjun ibn Mansur.[113] The latter had served Mu'awiya in this capacity before his attainment of the caliphate,[114] and Sarjun's father was the likely holder of the office under Emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641).[113] Mu'awiya was tolerant toward Syria's native Christian majority.[115] In turn, this community was generally satisfied with his rule, under which their conditions were at least as favorable as under the Byzantines.[115] Mu'awiya attempted to mint his own coins, but the new currency was rejected by the Syrians as it omitted the symbol of the cross.[116] In the sole epigraphic attestation to Mu'awiya's rule in Syria, a Greek inscription dated to 663 discovered at the hot springs of Hamat Gader near Lake Tiberias,[117] the caliph is referred to as "Abd Allah Mu'awiya, amīr al-muʾminīn" (God's Servant Mu'awiya, commander of the faithful) and is credited for restoring Roman-era bath facilities for the benefit of the sick; in the inscription, the caliph's name is preceded by a cross.[118] According to the historian Yizhar Hirschfeld, "by this deed, the new caliph sought to please" his Christian subjects.[118] The caliph often spent his winters at his Sinnabra palace near the shores of Lake Tiberias.[119] Mu'awiya was also credited with ordering the restoration of Edessa's church after it was ruined in an earthquake in 679.[120] Mu'awiya demonstrated a keen interest in Jerusalem.[121] Though archaeological evidence is lacking, there are indications in medieval literary sources that a rudimentary mosque on the Temple Mount existed as early as Mu'awiya's time or was built by him.[122][e]

Governance in the provinces

[edit]Mu'awiya's primary internal challenge was overseeing a Syria-based government which could reunite the politically and socially fractured Caliphate and assert authority over the tribes which formed its armies.[111] He applied indirect rule in the Caliphate's provinces, appointing governors with autonomy spanning full civil and military authority.[124] Though in principle governors were obliged to forward surplus tax revenues to the caliph,[111] in practice most of the surplus was distributed among the provincial garrisons and Damascus received a negligible share.[26][125] During Mu'awiya's caliphate, the governors relied on the ashrāf (tribal chieftains), who served as intermediaries between the authorities and the tribesmen in the garrisons.[111] Rather than the absolute government practiced by Caliph Ali, Mu'awiya's statecraft was likely inspired by his father, who utilized his wealth to establish political alliances.[125] The caliph generally preferred bribing his opponents over direct conflict.[125] In the summation of the historian Hugh Kennedy, Mu'awiya ruled by "making agreements with those who held power in the provinces, by building up the power of those who were prepared to co-operate with him and by attaching as many important and influential figures to his cause as possible".[125]

Iraq and the east

[edit]

Challenges to central authority in general and to Mu'awiya's rule in particular were most acute in Iraq, where divisions were rife between the ashrāf upstarts and the early Muslim elite, which was further divided between Ali's partisans and the Kharijites.[126] Mu'awiya's ascent signaled the rise of the Kufan ashrāf represented by Ali's erstwhile backers al-Ash'ath ibn Qays and Jarir ibn Abd Allah, at the expense of Ali's old guard represented by Hujr ibn Adi and Ibrahim, the son of Ali's leading aide Malik al-Ashtar.[127] Mu'awiya's initial choice to govern Kufa in 661 was al-Mughira ibn Shu'ba, who possessed considerable administrative and military experience in Iraq and was highly familiar with the region's inhabitants and issues.[127] Under his nearly decade-long administration, al-Mughira maintained peace in the city, overlooked transgressions that did not threaten his rule, allowed the Kufans to keep possession of the lucrative Sasanian crown lands in the Jibal district and, unlike under past administrations, consistently and timely paid the garrison's stipends.[127]

In Basra, Mu'awiya reappointed his Abd Shams kinsman Abd Allah ibn Amir, who had served the office under Uthman.[128] During Mu'awiya's reign, Ibn Amir recommenced expeditions into Sistan, reaching as far as Kabul.[129] He was unable to maintain order in Basra, where there was growing resentment toward the distant campaigns.[129] Consequently, Mu'awiya replaced Ibn Amir with Ziyad ibn Abihi in 664 or 665.[129] The latter had been the longest of Ali's loyalists to withhold recognition of Mu'awiya's caliphate and had barricaded himself in the Istakhr fortress in Fars.[130] Busr had threatened to execute three of Ziyad's young sons in Basra to force his surrender, but Ziyad was ultimately persuaded by al-Mughira, his mentor, to submit to Mu'awiya's authority in 663.[131] In a controversial step that secured the loyalty of the fatherless Ziyad, whom the caliph viewed as the most capable candidate to govern Basra,[129] Mu'awiya adopted him as his paternal half-brother to the protests of his own son Yazid, Ibn Amir and his Umayyad kinsmen in the Hejaz.[131][132]

Following al-Mughira's death in 670, Mu'awiya allotted Kufa and its dependencies to Ziyad's Basran governorship, making him the caliph's virtual viceroy over the eastern half of the Caliphate.[129] Ziyad tackled Iraq's core economic problem of overpopulation in the garrison cities and the consequent scarcity of resources by reducing the number of troops on the payrolls and dispatching 50,000 Iraqi soldiers and their families to settle Khurasan.[111] This also served to consolidate the previously weak and unstable Arab position in the Caliphate's easternmost province and enabled conquests toward Transoxiana.[111] As part of his reorganization efforts in Kufa, Ziyad confiscated its garrison's crown lands, which thenceforth became the possession of the caliph.[124] Opposition to this raised by Hujr ibn Adi,[111] whose pro-Alid advocacy had been tolerated by al-Mughira,[133] was violently suppressed by Ziyad.[111] Hujr and his retinue were sent to Mu'awiya for punishment and were executed on the caliph's orders, marking the first political execution in Islamic history and serving as a harbinger for future pro-Alid uprisings in Kufa.[132][134] After Ziyad's death in 673, Mu'awiya gradually replaced him in all of his offices with his son Ubayd Allah.[106] In effect, by relying on al-Mughira, Ziyad and his sons, Mu'awiya franchised the administration of Iraq and the eastern Caliphate to members of the elite Thaqif clan, which had long-established ties to the Quraysh and were instrumental in the conquest of Iraq.[106]

Egypt

[edit]In Egypt Amr governed as a virtual partner rather than a subordinate of Mu'awiya until his death in 664,[113] and was permitted to retain the surplus revenues of the province.[86] The caliph ordered the resumption of Egyptian grain and oil shipments to Medina, ending the hiatus caused by the First Fitna.[135] After Amr's death, Mu'awiya's brother Utba and an early companion of Muhammad, Uqba ibn Amir, successively served brief terms before Mu'awiya appointed Maslama ibn Mukhallad al-Ansari in 667.[86][113] Maslama remained governor for the duration of Mu'awiya's reign,[113] significantly expanding Fustat and its mosque and boosting the city's importance in 674 by relocating Egypt's main shipyard to the nearby Roda Island from Alexandria due to the latter's vulnerability to Byzantine naval raids.[136]

The Arab presence in Egypt was mostly limited to the central garrison at Fustat and the smaller garrison at Alexandria.[135] The influx of Syrian troops brought by Amr in 658 and the Basran troops sent by Ziyad in 673 swelled Fustat's 15,000-strong garrison to 40,000 during Mu'awiya's reign.[135] Utba increased the Alexandria garrison to 12,000 men and built a governor's residence in the city, whose Greek Christian population often rebelled against Arab rule.[137] When Utba's deputy in Alexandria complained that his troops were unable to control the city, Mu'awiya deployed a further 15,000 soldiers from Syria and Medina.[137] The troops in Egypt were far less rebellious than their Iraqi counterparts, though elements in the Fustat garrison occasionally raised opposition to Mu'awiya's policies, culminating during Maslama's term with the widespread protest at Mu'awiya's seizure and allotment of crown lands in Fayyum to his son Yazid, which compelled the caliph to reverse his order.[138]

Arabia

[edit]Although revenge for Uthman's assassination had been the basis upon which Mu'awiya claimed the right to the caliphate, he neither emulated Uthman's empowerment of the Umayyads nor used them to assert his own power.[125][139] With minor exception, members of the clan were not appointed to the wealthy provinces nor the caliph's court, Mu'awiya largely limiting their influence to Medina, the old capital of the Caliphate where most of the Umayyads and the wider Qurayshite former aristocracy remained headquartered.[125][140] The loss of political power left the Umayyads of Medina resentful toward Mu'awiya, who may have become wary of the political ambitions of the much larger Abu al-As branch of the clan—to which Uthman had belonged—under the leadership of Marwan ibn al-Hakam.[141] The caliph attempted to weaken the clan by provoking divisions between them.[142] Among the measures taken was the replacement of Marwan from the governorship of Medina in 668 with another leading Umayyad, Sa'id ibn al-As.[143] The latter was instructed to demolish Marwan's house, but refused and when Marwan was restored in 674, he also refused Mu'awiya's order to demolish Sa'id's home.[143] Mu'awiya dismissed Marwan once more in 678, replacing him with his own nephew, al-Walid ibn Utba.[144] Besides his own clan, Mu'awiya's relations with the Banu Hashim (the clan of the prophet Muhammad and Caliph Ali), the other families of Muhammad's closest companions, the once-prominent Banu Makhzum and the Ansar was generally characterized by hostility or suspicion.[145]

Despite his relocation to Damascus, Mu'awiya remained fond of his original homeland and made known his longing for "the spring in Jeddah [sic], the summer in Ta'if, [and] the winter in Mecca".[146] He purchased several large tracts throughout Arabia and invested considerable sums to develop the lands for agricultural use.[146] According to the Muslim literary tradition, in the plain of Arafat and the barren valley of Mecca he dug numerous wells and canals, constructed dams and dikes to protect the soil from seasonal floods, and built fountains and reservoirs.[146] His efforts saw extensive grain fields and date palm groves to spring up across Mecca's suburbs, which remained in this state until deteriorating during the Abbasid era, which began in 750.[146] In the Yamama in central Arabia, Mu'awiya confiscated from the Banu Hanifa the lands of Hadarim where he employed 4,000 slaves, likely to cultivate its fields.[147] The caliph gained possession of estates in and near Ta'if which, together with the lands of his brothers Anbasa and Utba, formed a considerable cluster of properties.[148] One of the earliest known Arabic inscriptions from Mu'awiya's reign was found at a soil-conservation dam called Sayisad 20 miles east of Ta'if, which credits Mu'awiya for the dam's construction in 677/78 and asks God to give him victory and strength.[149]

War with Byzantium

[edit]

Mu'awiya possessed more personal experience than any other caliph fighting the Byzantines,[150] the principal external threat to the Caliphate,[51] and pursued the war against the Empire more energetically and continuously than his successors.[151] The First Fitna caused the Arabs to lose control over Armenia to native, pro-Byzantine princes, but in 661 Habib ibn Maslama re-invaded the region.[45] The following year, Armenia became a tributary of the Caliphate and Mu'awiya recognized the Armenian prince Grigor Mamikonian as its commander.[45] Not long after the civil war, Mu'awiya broke the truce with Byzantium,[152] and on a near-annual or bi-annual basis the caliph engaged his Syrian troops in raids across the mountainous Anatolian frontier,[113] the buffer zone between the Empire and the Caliphate.[153] At least until Abd al-Rahman's death in 666, Homs served as the principal marshaling point for the offensives, and afterward Antioch served this purpose as well.[154] The bulk of the troops fighting on the Anatolian and Armenian fronts hailed from the tribal groups that arrived from Arabia during and after the conquest.[28]

Based on the histories of al-Tabari (d. 923) and Agapius of Hierapolis (d. 941), the first raid of Mu'awiya's caliphate occurred in 662/63, during which his forces inflicted a heavy defeat on a Byzantine army with numerous patricians slain.[152] In the next year a raid led by Busr reached Constantinople and in 664/65, Abd al-Rahman raided Koloneia in northeastern Anatolia.[152] In the late 660s, Mu'awiya's forces attacked Antioch of Pisidia or Antioch of Isauria.[152] According to the Muslim traditional sources, the raids peaked between 668/69 and 669/70.[152] In each of those years there occurred six ground campaigns and a major naval campaign, the first by an Egyptian and Medinese fleet and the second by an Egyptian and Syrian fleet.[155] In addition to these offensives, al-Tabari reports that Mu'awiya's son Yazid led a campaign against Constantinople in 669 and Ibn Abd al-Hakam reports that the Egyptian and Syrian navies led respectively by Uqba ibn Amir and Fadhala ibn Ubayd joined the assault.[156] The modern historian Marek Jankowiak asserts that the multitude of campaigns that were reported during these two years represent coordinated efforts by Mu'awiya to conquer the Byzantine capital.[157] Dismissing the conventional view of a many years-long siege of Constantinople in the 670s, which was based on the history of the Byzantine chronicler Theophanes the Confessor (d. 818), Jankowiak asserts that Mu'awiya likely ordered the invasion during an opportunity presented by the rebellion of the Byzantine Armenian general Saborios, who formed a pact with the caliph, in spring 667.[158] The caliph dispatched an army under Fadhala ibn Ubayd, but before it could be joined by the Armenians, Saborios died.[158] Mu'awiya then sent reinforcements led by Yazid who led the Arab army's invasion in the summer.[158] An Arab fleet reached the Sea of Marmara by autumn, while Yazid and Fadhala, having raided Chalcedon through the winter, besieged Constantinople in spring 668, but due to famine and disease, lifted the siege in late June.[159] The Arabs continued their campaigns in Constantinople's vicinity before withdrawing to Syria most likely in late 669.[159]

Following the death of Emperor Constans II in July 668, Mu'awiya oversaw an increasingly aggressive policy of naval warfare against the Byzantines.[51] He continued his past efforts to resettle and fortify the Syrian port cities.[51] Due to the reticence of Arab tribesmen to inhabit the coastlands, in 663 Mu'awiya moved Persian civilians and personnel that he had previously settled in the Syrian interior into Acre and Tyre, and transferred elite Persian soldiers from Kufa and Basra to the garrison at Antioch.[31][38] A few years later, Mu'awiya settled Apamea with 5,000 Slavs who had defected from the Byzantines during one of his forces' Anatolian campaigns.[31] In 669, Mu'awiya's navy raided as far as Sicily.[51] In 670, the wide-scale fortification of Alexandria was completed.[51]

While the histories of al-Tabari and al-Baladhuri report that Mu'awiya's forces captured Rhodes in 672–674 and colonized the island for seven years before withdrawing during the reign of Yazid I, the modern historian Clifford Edmund Bosworth casts doubt on these events and holds that the island was only raided by Mu'awiya's lieutenant Junada ibn Abi Umayya al-Azdi in 679/80.[160] Under Emperor Constantine IV (r. 668–685), the Byzantines began a counteroffensive against the Caliphate, first raiding Egypt in 672 or 673,[161] while in winter 673, Mu'awiya's admiral Abd Allah ibn Qays led a large fleet that raided Smyrna and the coasts of Cilicia and Lycia.[162] The Byzantines landed a major victory against an Arab army and fleet led by Sufyan ibn Awf, possibly at Sillyon, in 673/74.[163] The next year, Abd Allah ibn Qays and Fadhala landed in Crete and in 675/76, a Byzantine fleet assaulted Maraqiya, killing the governor of Homs.[161] In 677, 678 or 679 Mu'awiya sued for peace with Constantine IV, possibly as a result of the destruction of his fleet or the Byzantines' deployment of the Mardaites in the Syrian littoral during that time.[164] A thirty-year treaty was concluded, obliging the Caliphate to pay an annual tribute of 3,000 gold coins, 50 horses and 50 slaves, and withdraw their troops from the forward bases they had occupied on the Byzantine coast.[165] Though the Muslims did not achieve any permanent territorial gains in Anatolia during Mu'awiya's career, the frequent raids provided Mu'awiya's Syrian troops with war spoils and tribute, which helped ensure their continued allegiance, and sharpened their combat skills.[166] Moreover, Mu'awiya's prestige was boosted and the Byzantines were precluded from any concerted campaigns against Syria.[167]

Conquest of central North Africa

[edit]

The expeditions against Byzantine North Africa were renewed during Mu'awiya's reign, the Arabs not having advanced beyond Cyrenaica since the 640s other than periodic raids.[168] In 665/66 Ibn Hudayj led an army which raided Byzacena (southern district of Byzantine Africa) and Gabes and temporarily captured Bizerte before withdrawing to Egypt.[169] The following year Mu'awiya dispatched Fadhala and Ruwayfi ibn Thabit to raid the commercially valuable island of Jerba.[169] Meanwhile, in 662 or 667, Uqba ibn Nafi, a Qurayshite commander who had played a key role in the Arabs' capture of Barqa in 641, reasserted Muslim influence in the Fezzan region, capturing the Zawila oasis and the Garamantes capital of Germa.[170] He may have raided as far south as Kawar in modern-day Niger.[170]

The struggle over the succession of Constantine IV drew Byzantine focus away from the African front.[171] In 670, Mu'awiya appointed Uqba as Egypt's deputy governor over the North African lands under Arab control and, at the head of 10,000 men from Egypt, Uqba commenced his expedition against the territories west of Cyrenaica.[172] As he advanced, his army was joined by Islamized Luwata Berbers and their combined forces conquered Ghadamis, Gafsa and the Jarid.[170][172] In the last region he established a permanent Arab garrison town called Kairouan a relatively safe distance from Carthage and the coastal areas, which had remained under Byzantine control, to serve as a base for further expeditions.[173] It also aided Muslim conversion efforts among the Berber tribes that dominated the surrounding countryside.[173]

Mu'awiya dismissed Uqba in 673, likely out of concern that he would form an independent power base in the lucrative regions that he conquered.[173] The new Arab province, Ifriqiya (modern-day Tunisia), remained subordinate to the governor of Egypt, who sent his mawlā (non-Arab, Muslim freedman) Abu al-Muhajir Dinar to replace Uqba, who was arrested and transferred to Mu'awiya's custody in Damascus.[173] Abu al-Muhajir continued the westward campaigns as far as Tlemcen and defeated the Awraba Berber chief Kasila, who subsequently embraced Islam and joined his forces.[173] In 678, a treaty between the Arabs and the Byzantines ceded Byzacena to the Caliphate, while forcing the Arabs to withdraw from the northern parts of the province.[171] After Mu'awiya's death, his successor Yazid reappointed Uqba, Kasila defected and a Byzantine–Berber alliance ended Arab control over Ifriqiya,[173] which was not reestablished until the reign of Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (r. 685–705).

Nomination of Yazid as successor

[edit]In a move unprecedented in Islamic politics, Mu'awiya nominated his own son, Yazid, as his successor.[166] The caliph likely held ambitions for his son's succession over a considerable period.[174] In 666, he allegedly had his governor in Homs, Abd al-Rahman ibn Khalid, poisoned to remove him as a potential rival to Yazid.[175] The Syrian Arabs, with whom Abd al-Rahman was popular, had viewed the governor as the caliph's most suitable successor by dint of his military record and descent from Khalid ibn al-Walid.[176][f] It was not until the latter half of his reign that Mu'awiya declared Yazid heir apparent, though the traditional Muslim sources offer divergent details about the timing and location of the events relating to the decision.[183] The accounts of al-Mada'ini (752–843) and Ibn al-Athir (1160–1232) agree that al-Mughira was the first to suggest that Yazid be acknowledged as Mu'awiya's successor and that Ziyad supported the nomination with the caveat that Yazid abandon impious activities which could arouse opposition from the Muslim polity.[184] According to al-Tabari, Mu'awiya publicly announced his decision in 675/76 and demanded oaths of allegiance be given to Yazid.[185] Ibn al-Athir alone relates that delegations from all the provinces were summoned to Damascus where Mu'awiya lectured them on his rights as ruler, their duties as subjects and Yazid's worthy qualities, which was followed by the calls of al-Dahhak ibn Qays and other courtiers that Yazid be recognized as the caliph's successor. The delegates lent their support, with the exception of the senior Basran nobleman al-Ahnaf ibn Qays, who was ultimately bribed into compliance.[186] Al-Mas'udi (896–956) and al-Tabari do not mention such provincial delegations other than a Basran embassy led by Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad in 678/79 or 679/80, respectively, which recognized Yazid.[187]

According to Hinds, in addition to Yazid's nobility, age and sound judgement, "most important of all was the fact that he represented a continuation of the link with Kalb and so a continuation of the Kalb-led [tribal] confederacy on which Sufyanid power ultimately rested".[26] In nominating Yazid, the son of the Kalbite Maysun, Mu'awiya bypassed his older son Abd Allah from his Qurayshite wife Fakhita.[188] Though support from the Kalb and the broader Quda'a group was guaranteed, Mu'awiya exhorted Yazid to widen his tribal support base in Syria. As the Qaysites were the predominant element in the northern frontier armies, Mu'awiya's appointment of Yazid to lead the war efforts with Byzantium may have served to foster Qaysite support for his nomination.[189] Mu'awiya's efforts to that end were not entirely successful as reflected in a line by a Qaysite poet: "we will never pay allegiance to the son of a Kalbi woman [i.e. Yazid]".[190][191]

In Medina, Mu'awiya's distant kinsmen Marwan ibn al-Hakam, Sa'id ibn al-As and Ibn Amir accepted Mu'awiya's succession order, albeit disapprovingly.[192] Most opponents of Mu'awiya's order in Iraq and among the Umayyads and Quraysh of the Hejaz were ultimately threatened or bribed into acceptance.[166] The remaining principle opposition emanated from Husayn ibn Ali, Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr, Abd Allah ibn Umar and Abd al-Rahman ibn Abi Bakr, all prominent Medina-based sons of earlier caliphs or close companions of Muhammad.[193] As they possessed the nearest claims to the caliphate, Mu'awiya was determined to obtain their recognition.[194][195] Before his death, Mu'awiya ordered certain measures be taken against them, entrusting these tasks to his loyalists al-Dahhak ibn Qays and Muslim ibn Uqba, according to Awana ibn al-Hakam (d. 764).[196]

Death

[edit]Mu'awiya died of an illness in Damascus in Rajab 60 AH (April–May 680 CE).[1][197] The medieval accounts vary regarding the specific date of his death, with Hisham ibn al-Kalbi (d. 819) placing it on 7 April, al-Waqidi on 21 April and al-Mada'ini on 29 April.[198] Yazid, who was away from Damascus at the time of his father's death,[199] is held by Abu Mikhnaf (d. 774) to have succeeded him on 7 April, while the Nestorian chronicler Elias of Nisibis (d. 1046) says it occurred on 21 April.[200] In his last testament, Mu'awiya told his family "Fear God, Almighty and Great, for God, praise Him, protects whoever fears Him, and there is no protector for one who does not fear God".[201] He was buried next to the Bab al-Saghir gate of the city and the funeral prayers were led by al-Dahhak ibn Qays, who mourned Mu'awiya as the "stick of the Arabs and the blade of the Arabs, by means of whom God, Almighty and Great, cut off strife, whom He made sovereign over mankind, by means of whom he conquered countries, but now he has died".[202]

Mu'awiya's grave was a visitation site as late as the 10th century. Al-Mas'udi (d. 956) holds that a mausoleum was built over the grave and was open to visitors on Mondays and Thursdays. Ibn Taghribirdi asserts that Ahmad ibn Tulun, the autonomous 9th-century ruler of Egypt and Syria, erected a structure on the grave in 883/84 and employed members of the public to regularly recite the Qur'an and light candles around the tomb.[203]

Legacy and assessment

[edit]“Muʿāwiya […] stands out in the archaeological record as the first Muslim ruler whose name appears on coins” - Jeremy Johns.[204]

Notes

[edit]- ^ According to the historian, Khalil Athamina, Caliph Umar's efforts to make the native Syrian Arab tribes the foundation of Syria's defense from a Byzantine counterattack was the main cause of Khalid ibn al-Walid's dismissal from the general command in Syria and the subsequent recall to Iraq of the numerous tribesmen in Khalid's army, who were likely perceived as a threat by the Banu Kalb and its allies, in 636.[24] The Quraysh and the early Muslim elite sought to secure Syria, with which they had long been acquainted, for themselves and encouraged the nomadic Arab late converts among the Muslim troops to immigrate to Iraq.[25] According to Madelung, Umar may have promoted Yazid and Mu'awiya as guarantors of the caliphate's authority in Syria against the growing "strength and high ambitions" of the South Arabian, aristocratic Himyarites, who had played a prominent role in the Muslim conquest.[13]

- ^ After Mu'awiya divorced Na'ila bint Umara al-Kalbiyya, she was wed to Mu'awiya's close aide Habib ibn Maslama al-Fihri and after the latter's death, to another of Mu'awiya's close aides, Nu'man ibn Bashir al-Ansari.[30]

- ^ The nepotistic policies of Caliph Uthman included the appointment of his relatives to all of the Caliphate's major governorships, namely Syria and the Jazira under his Umayyad cousin Mu'awiya, Kufa successively under the Umayyads al-Walid ibn Uqba and Sa'id ibn al-As, Basra with Bahrayn and Oman under Uthman's maternal cousin Abd Allah ibn Amir of the Banu Abd Shams clan, Mecca under Ali ibn Adi ibn Rabi'a of the Banu Abd Shams and Egypt under Uthman's foster brother Abd Allah ibn Abi Sarh, and reliance on his cousin Marwan ibn al-Hakam in his internal decision-making.[49]

- ^ The consensus in the Muslim traditional sources holds that Caliph Ali's Iraqi forces gained the advantage during the battle prompting the Syrians to appeal for a settlement by arbitration. This is contested by a number of non-Muslim historians, including Martin Hinds, according to whom the Syrians were victorious, an assertion supported by Umayyad court poetry.[51]

- ^ The Christian pilgrim Arculf visited Jerusalem between 679 and 681 and noted that a makeshift Muslim prayer house built of beams and clay with a capacity for 3,000 worshipers had been erected on the Temple Mount, while a Jewish midrash confirms that Mu'awiya rebuilt the Temple Mount's walls. The mid-10th-century Arabic chronicler al-Mutahhar ibn Tahir al-Maqdisi explicitly states that Mu'awiya built a mosque on the site.[123]

- ^ The claim that Mu'awiya had Abd al-Rahman ibn Khalid poisoned by his Christian doctor Ibn Uthal is found in the medieval Islamic histories of al-Mada'ini, al-Tabari, al-Baladhuri and Mus'ab al-Zubayri, among others[177][178] and is accepted by historian Wilferd Madelung,[179] while historians Martin Hinds and Julius Wellhausen consider Mu'awiya's role in the affair as an allegation of the Muslim traditional sources.[178][180] The Orientalists Michael Jan de Goeje and Henri Lammens dismiss the claim;[181][182] the former called it an "absurdity" and "incredible" that Mu'awiya "would have deprived himself of one of his best men" and the more likely scenario was that Abd al-Rahman had been ill and Mu'awiya attempted to have him treated by Ibn Uthal, who was unsuccessful. De Goeje further doubts the credibility of the reports as they originated in Medina, the home of his Banu Makhzum clan, rather than Homs where Abd al-Rahman had died.[181]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Hinds 1993, p. 264.

- ^ a b Watt 1960, p. 151. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWatt1960 (help)

- ^ Hawting 2000, pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, p. 241.

- ^ Watt 1960, p. 868. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFWatt1960 (help)

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, p. 45.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 60.

- ^ Donner 1981, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Donner 1981, p. 154.

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b c d Madelung 1997, p. 61.

- ^ Donner 1981, p. 153.

- ^ Sourdel 1965, p. 911.

- ^ Kaegi 1992, pp. 67, 246.

- ^ Kaegi 1992, p. 245.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 86.

- ^ a b Dixon 1978, p. 493.

- ^ Lammens 1960, p. 920.

- ^ Donner 1981, p. 106.

- ^ a b Marsham 2013, p. 104.

- ^ Athamina 1994, p. 263.

- ^ Athamina 1994, pp. 262, 265–268.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2007, p. 95.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hinds 1993, p. 267.

- ^ a b Wellhausen 1927, pp. 55, 132.

- ^ a b Humphreys 2006, p. 61.

- ^ Morony 1987, p. 215.

- ^ a b c Morony 1987, pp. 215–216. Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTEMorony1987215–216" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jandora 1986, p. 111.

- ^ a b c Donner 1981, p. 245.

- ^ a b Jandora 1986, p. 112.

- ^ Shahid 2000, p. 191. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFShahid2000 (help)

- ^ Shahid 2000, p. 403. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFShahid2000 (help)

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 82.

- ^ Donner 1981, pp. 248–249.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2001, p. 12.

- ^ Donner 1981, p. 248.

- ^ a b c Bosworth 1996, p. 157.

- ^ a b c d Lynch 2016, p. 539.

- ^ a b Lynch 2016, p. 540.

- ^ Lynch 2016, pp. 541–542.

- ^ Kaegi 1992, pp. 184–185.

- ^ a b c d Kaegi 1992, p. 185.

- ^ Bosworth 1996, p. 158.

- ^ a b Bosworth 1996, pp. 157–158.

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, p. 84.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 86–89.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hinds 1993, p. 265.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 52.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, p. 76.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 55–56, 76.

- ^ a b Wellhausen 1927, p. 76.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 184.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 190.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 191, 196.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 199.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 224.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 203.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 222.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 225–226, 229.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 230–231.

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, p. 231.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 232.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 233–234.

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, pp. 237–238.

- ^ a b Lecker 1997, p. 383.

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, p. 238.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 78.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 242–243.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 79.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 245.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 247.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 243.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 254–255.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 255.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 256–257.

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, p. 257.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 258.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy 1998, p. 69.

- ^ a b c Wellhausen 1927, p. 99.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 262–263, 287.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 100.

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, p. 289.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 290–292.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 299.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 300.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 301–303.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 304–305.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 305.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 307.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 104.

- ^ a b Marsham 2013, p. 93.

- ^ Marsham 2013, p. 96.

- ^ Marsham 2013, p. 97.

- ^ Marsham 2013, pp. 87, 89, 101.

- ^ Marsham 2013, pp. 94, 106.

- ^ a b c Wellhausen 1927, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 86.

- ^ Crone 1994, p. 44.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Hawting 1996, p. 223.

- ^ Kennedy 2001, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hinds 1993, p. 266.

- ^ Crone 1994, p. 45, note 239.

- ^ a b c d e f Kennedy 2004, p. 87.

- ^ Sprengling 1939, p. 182.

- ^ a b Wellhausen 1927, p. 134.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 842.

- ^ Foss 2010, p. 83.

- ^ a b Hirschfeld 1987, p. 107.

- ^ Hasson 1982, p. 99.

- ^ Hoyland 1999, p. 159.

- ^ Elad 1999, p. 23.

- ^ Elad 1999, p. 33.

- ^ Elad 1999, pp. 23–24, 33.

- ^ a b Hinds 1993, pp. 266–267.

- ^ a b c d e f Kennedy 2004, p. 83.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 84.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b c d e Kennedy 2004, p. 85.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 120.

- ^ a b Wellhausen 1927, p. 121.

- ^ a b Hasson 2002, p. 520.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 124.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 41.

- ^ a b c Foss 2009, p. 268.

- ^ Foss 2009, p. 269.

- ^ a b Foss 2009, p. 272.

- ^ Foss 2009, pp. 269–270.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 135.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Bosworth 1991, pp. 621–622.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 136.

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, p. 345, note 90.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 346.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 136–137.

- ^ a b c d Miles 1948, p. 236.

- ^ Dixon 1969, p. 297.

- ^ Miles 1948, p. 238.

- ^ Miles 1948, p. 237.

- ^ Kaegi 1992, p. 247.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d e Jankowiak 2013, p. 273.

- ^ Kaegi 1992, pp. 244–245, 247.

- ^ Kaegi 1992, pp. 245, 247.

- ^ Jankowiak 2013, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Jankowiak 2013, pp. 267, 274.

- ^ Jankowiak 2013, p. 290.

- ^ a b c Jankowiak 2013, pp. 303–304.

- ^ a b Jankowiak 2013, pp. 304, 316.

- ^ Bosworth 1996, pp. 159–160.

- ^ a b Jankowiak 2013, p. 316.

- ^ Jankowiak 2013, p. 318.

- ^ Jankowiak 2013, pp. 278–279, 316.

- ^ Stratos 1978, p. 46.

- ^ Lilie 1976, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 88.

- ^ Kaegi 1992, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Kennedy 2007, pp. 207–208.

- ^ a b Kaegi 2010, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Christides 2000, p. 789.

- ^ a b Kaegi 2010, p. 13.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2007, p. 209.

- ^ a b c d e f Christides 2000, p. 790.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 146.

- ^ Hinds 1991, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 339–340.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 340–341.

- ^ a b Hinds 1991, p. 139.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 340–342.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 137.

- ^ a b De Goeje 1910, p. 28.

- ^ Gibb 1960, p. 85.

- ^ Marsham 2013, p. 90.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 141, 143.

- ^ Morony 1987, p. 183.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 142.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Hawting 2002, p. 309.

- ^ Marsham 2013, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Marsham 2013, p. 91.

- ^ Crone 1994, p. 45.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 342–343.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 142, 144–145.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 43.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 144–145.

- ^ Morony 1987, p. 210, 212–213.

- ^ Morony 1987, p. 210.

- ^ Morony 1987, pp. 209, 213–214.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 139.

- ^ Morony 1987, p. 213.

- ^ Morony 1987, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Grabar 1966, p. 18.

- ^ Whitcomb, p. 22.

Bibliography

[edit]- Athamina, Khalil (July 1994). "The Appointment and Dismissal of Khalid ibn al-Walid from the Supreme Command: A Study of the Political Strategy of the Early Muslim Caliphs in Syria". Arabica. 41 (2). Brill: 253–272. doi:10.1163/157005894X00191. JSTOR 4057449.

- Bosworth, C.E. (1991). "Marwān I b. al-Ḥakam". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VI: Mahk–Mid. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 621–623. ISBN 978-90-04-08112-3.

- Bosworth, C. Edmund (July 1996). "Arab Attacks on Rhodes in the Pre-Ottoman Period". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 6 (2): 157–164. doi:10.1017/S1356186300007161. JSTOR 25183178.

- Christides, Vassilios (2000). "ʿUkba b. Nāfiʿ". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 789–790. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Crone, Patricia (1994). "Were the Qays and Yemen of the Umayyad Period Political Parties?". Der Islam. 71 (1). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co.: 1–57. doi:10.1515/islm.1994.71.1.1. ISSN 0021-1818.

- De Goeje, M. J. (1910). "Caliphate". The Encyclopaedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information, Volume V: Calhoun to Chatelaine (11th ed.). New York. pp. 35–54. OCLC 62674231.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dixon, 'Abd al-Ameer (August 1969), The Umayyad Caliphate 65–86/684–705: A Political Study, London: University of London SOAS

- Dixon, A. A. (1978). "Kalb b. Wabara—Islamic Period". In van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume IV: Iran–Kha. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 493–494. OCLC 758278456.

- Donner, Fred M. (1981). The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05327-8.

- Elad, Amikam (1999). Medieval Jerusalem and Islamic Worship: Holy Places, Ceremonies, Pilgrimage (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-10010-5.

- Foss, Clive (2010). "Muʿāwiya's State". In Haldon, John (ed.). Money, Power and Politics in Early Islamic Syria: A Review of Current Debates. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-6849-7.

- Foss, Clive (2009). "Egypt under Muʿāwiya Part II: Middle Egypt, Fusṭāṭ and Alexandria". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 72 (2): 259–278. doi:10.1017/S0041977X09000512. JSTOR 40379004.

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1960). "ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Khālid b. al-Walīd". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 85. OCLC 495469456.

- Hasson, Isaac (1982). "Remarques sur l'inscription de l'époque de Mu'āwiya à Ḥammat Gader". Israel Exploration Journal (in French). 32 (2/3): 97–102. JSTOR 27925830.

- Hasson, I. (2002). "Ziyād b. Abīhi". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume XI: W–Z. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 519–522. ISBN 978-90-04-12756-2.

- Hawting, G. R., ed. (1996). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XVII: The First Civil War: From the Battle of Siffīn to the Death of ʿAlī, A.D. 656–661/A.H. 36–40. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2393-6.

- Hawting, Gerald R. (2000). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661–750 (Second ed.). London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24072-7.

- Hawting, G. R. (2002). "Yazīd (I) b. Muʿāwiya". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume XI: W–Z. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 309–311. ISBN 978-90-04-12756-2.

- Hinds, M. (1991). "Makhzūm". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VI: Mahk–Mid. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 137–140. ISBN 978-90-04-08112-3.

- Hinds, M. (1993). "Muʿāwiya I b. Abī Sufyān". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 263–268. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Hirschfeld, Yizhar (1987). "The History and Town-Plan of Ancient Ḥammat Gādẹ̄r". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins (1953-). 103: 101–116. JSTOR 27931308.

- Hoyland, Robert G. (1999). "Jacob of Edessa on Islam". In Reinink, G. J.; Klugkist, A. C. (eds.). After Bardaisan: Studies on Continuity and Change in Syriac Christianity in Honour of Professor Han J. W. Drijvers. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 90-429-0735-5.

- Humphreys, R. Stephen (2006). Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan: From Arabia to Empire. Oneworld. ISBN 1-85168-402-6.

- Jandora, J. W. (1986). "Developments in Islamic Warfare: The Early Conquests". Studia Islamica (64): 101–113. doi:10.2307/1596048. JSTOR 1596048.

- Jankowiak, Marek (2013). "The First Arab Siege of Constantinople". In Zuckerman, Constantin (ed.). Travaux et mémoires, Vol. 17: Constructing the Seventh Century. Paris: Association des Amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance. pp. 237–320.

- Kaegi, Walter E. (1992). Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-41172-6.

- Kaegi, Walter E. (2010). Muslim Expansion and Byzantine Collapse in North Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19677-2.

- Kennedy, Hugh (1998). "Egypt as a Province in the Islamic Caliphate, 641–868". In Petry, Carl F. (ed.). Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume One: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 62–85. ISBN 0-521-47137-0.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25092-7.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2007). The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In. Philadelphia: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81585-0.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Lammens, Henri (1960). "Baḥdal". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 919–920. OCLC 495469456.

- Lecker, M. (1997). "Ṣiffīn". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 552–556. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- Lilie, Ralph-Johannes (1976). Die byzantinische Reaktion auf die Ausbreitung der Araber. Studien zur Strukturwandlung des byzantinischen Staates im 7. und 8. Jhd (in German). Munich: Institut für Byzantinistik und Neugriechische Philologie der Universität München. OCLC 797598069.

- Lynch, Ryan J. (July–September 2016). "Cyprus and Its Legal and Historiographical Significance in Early Islamic History". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 136 (3): 535–550. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.3.0535. JSTOR 10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.3.0535.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - Madelung, Wilferd (1997). The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56181-7.

- Marsham, Andrew (2013). "The Architecture of Allegiance in Early Islamic Late Antiquity: The Accession of Mu'awiya in Jerusalem, ca. 661 CE". In Beihammer, Alexander; Constantinou, Stavroula; Parani, Maria (eds.). Court Ceremonies and Rituals of Power in Byzantium and the Medieval Mediterranean. Leiden and Boston: Brill. pp. 87–114. ISBN 978-90-04-25686-6.

- Miles, George C. (October 1948). "Early Islamic Inscriptions Near Ṭāʾif in the Ḥijāz". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 7 (4): 236–242. doi:10.1086/370887. JSTOR 542216.

- Morony, Michael G., ed. (1987). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XVIII: Between Civil Wars: The Caliphate of Muʿāwiyah, 661–680 A.D./A.H. 40–60. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-933-9.

- Shahid, Irfan (2009). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Volume 2, Part 2. Washington, D. C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 978-0-88402-347-0.

- Shahid, I. (2000). "Tanūkh". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 190–192. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Shahid, I. (2000). "Ṭayyīʾ". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 402–403. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Shahin, Aram A. (2012). "In Defense of Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan: Treatises and Monographs on Mu'awiya from the Eighth to Nineteenth Centuries". In Cobb, Paul M. (ed.). The Lineaments of Islam: Studies in Honor of Fred McGraw Donner. Leiden and Boston: Brill. pp. 177–208. ISBN 978-90-04-21885-7.

- Sourdel, D. (1965). "Filasṭīn — I. Palestine under Islamic Rule". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 910–913. OCLC 495469475.

- Sprengling, Martin (April 1939). "From Persian to Arabic". The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. 56 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 175–224. doi:10.1086/370538. JSTOR 528934.

- Stratos, Andreas N. (1978). Byzantium in the Seventh Century, Volume IV: 668–685. Amsterdam: Adolf M. Hakkert. ISBN 9789025606657.

- Watt, W. Montgomery (1960). "Abū Sufyān". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 151. OCLC 495469456.

- Watt, W. Montgomery (1960). "Badr". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 866–867. OCLC 495469456.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1927). The Arab Kingdom and Its Fall. Translated by Margaret Graham Weir. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. OCLC 752790641.