User:Al Ameer son/Al-Walid I

| Al-Walid I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khalīfat Allāh | |||||

| Caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate | |||||

| Reign | 9 October 705 – 25 January or 11 March 715 | ||||

| Predecessor | Abd al-Malik | ||||

| Successor | Sulayman | ||||

| Born | 674 Medina, Umayyad Caliphate | ||||

| Died | 25 January or 11 March 715 Dayr Murran, Umayyad Caliphate | ||||

| Burial | Damascus, Umayyad Caliphate | ||||

| Consort | Umm al-Banin bint Abd al-Aziz ibn Marwan Umm ʿAbdallāh bint ʿAbdallāh ibn ʿAmr ibn ʿUthmān ʿIzza bint ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz ibn ʿAbdallāh ibn ʿAmr Shah-i Afrid bint Peroz III | ||||

| Issue | ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz Al-ʿAbbās Yazīd III Ibrāhīm Muḥammad ʿUmar Bishr Rawḥ Khālid Tammām Mubashshir Jurayy ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Yaḥyā Abū ʿUbayda Masrūr Ṣadaqa | ||||

| |||||

| House | Marwanid | ||||

| Dynasty | Umayyad | ||||

| Father | ʿAbd al-Malik | ||||

| Mother | Wallāda bint al-ʿAbbās ibn al-Jazʾ al-ʿAbsīyya | ||||

Al-Walīd ibn ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān (circa 674 – 25 January or 11 March 715) was the sixth Umayyad caliph, ruling between 705 and his death. The eldest son of his predecessor, Caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 705–715), al-Walid largely continued his father's policies of centralization and expansion, though he was heavily dependent on al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, his father's powerful viceroy of the eastern half of the caliphate. During his reign, the Umayyad armies conquered Spain, Sindh and Transoxiana. War spoils from the conquest allowed al-Walid to finance public works of great magnitude, including the Great Mosque of Damascus, the al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem and the Prophet's Mosque in Medina. He was the first caliph to institute programs for social welfare, aiding the poor and handicapped. Though it is difficult to ascertain al-Walid's direct role in the affairs of his caliphate, his reign was marked by domestic peace and prosperity and represented the peak of the Umayyads' territorial extent.

Early life

[edit]Al-Walid was born around 674 in Medina.[1] His father was Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, a member of the Banu Umayya clan.[1] At the time of al-Walid's birth, another Umayyad, Mu'awiya I, was caliph.[1] The latter hailed from the Sufyanid branch of the clan resident in Syria, while al-Walid's family belonged to the larger Abu'l-'As line in the Hejaz (western Arabia). Al-Walid's mother was Wallada bint al-'Abbas ibn al-Jaz', a fourth-generation descendant of the 6th-century Arab chieftain Zuhayr ibn Jadhima of the Banu Abs clan of Ghatafan.[1][2] When Umayyad rule collapsed in 684, the Umayyads of the Hejaz were expelled by a rival claimant to the caliphate, Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr. After reaching Syria, al-Walid's grandfather, Marwan I, who was the most senior Umayyad at the time, was recognized as caliph by the pro-Umayyad Arab tribes of the province and gradually restored the dynasty's rule there and in Egypt.[3] Abd al-Malik succeeded Marwan and conquered the rest of the caliphate, namely Iraq with its eastern dependencies and the Hejaz.[4] With the key assistance of his viceroy in Iraq, al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, he instituted several centralization measures, which consolidated Umayyad territorial gains.[5]

Caliphate

[edit]Abd al-Malik, encouraged by al-Hajjaj, unsuccessfully attempted to nominate al-Walid as his successor, abrogating the arrangement set by Marwan whereby Abd al-Malik's brother Abd al-Aziz, governor of Egypt, was slated to succeed.[6][7] However, the latter died in 704, removing the principal obstacle to al-Walid's nomination and he acceded after the death Abd al-Malik on 9 October 705.[1][6] From the outset of his rule, al-Walid was heavily dependent on al-Hajjaj and allowed him free reign over the eastern half of the caliphate.[7] Moreover, al-Hajjaj strongly influenced al-Walid's internal decision-making, with officials being installed and dismissed upon the viceroy's wishes.[7] Al-Hajjaj's prominence was such that he is discussed more frequently in medieval Muslim sources than al-Walid or Abd al-Malik and his time in office (694–714) created a unity to the period of the two caliphs.[8] Thus, al-Walid's reign would largely serve as a continuation of his father's policies of centralization and expansion.[1][9]

Territorial expansion

[edit]

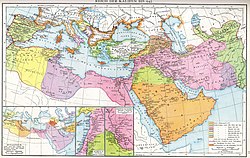

During the second half of al-Walid's reign, the Umayyad Caliphate reached its furthest territorial extent.[9] Expansion of the eastern frontier regions was overseen by al-Hajjaj from Iraq.[1] He carefully chose, equipped and generously financed the commanders of the expeditions, without personally participating.[7] His lieutenant governor of Khurasan, Qutayba ibn Muslim, launched numerous campaigns against Transoxiana (Central Asia), which had been a largely impenetrable region for earlier Muslim armies, between 705 and 715.[1] Through his persistent raids, he gained the surrender of Bukhara in 706–709, Khwarazm and Samarkand in 711–712 and Farghana in 713.[1] In contrast to most other Muslim conquests, Qutayba did not attempt to settle Arab Muslims in Transoxiana, instead securing Umayyad suzerainty through tributary alliances with local rulers, whose power remained intact.[10] From 708/09, al-Hajjaj's nephew and lieutenant commander, Qasim ibn Muhammad, conquered Sindh, the western region of South Asia, while another of al-Hajjaj's appointees, Mujja'a ibn Si'r, wrested control of Uman, along Arabia's southeastern coast.[7][11] In the west, under the supervision of al-Walid's governor in Ifriqiya, Musa ibn Nusayr, the Umayyad army of Tariq ibn Ziyad invaded the Spain in 711.[9] By 716, a year after al-Walid's death, the region had been nearly conquered.[9] The war spoils netted by the conquests of Transoxiana, Sindh and Spain were comparable to the amounts accrued in the early Muslim conquests during the reign of Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab (r. 634–644).[12]

Closer to the Umayyad seat of power in Syria, al-Walid appointed his half-brother Maslama governor of the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia) and charged him with raiding the frontier zone with Byzantium.[1] Though Maslama established a strong power base in his province, he achieved minor territorial gains.[1] Al-Walid entrusted most of the military governorships of Syria's districts to his sons.[13][14] Al-Abbas was assigned to Hims and fought reputably in the campaigns against Byzantium alongside Maslama, while Abd al-Aziz, who also took part in the anti-Byzantine war effort, and Umar were appointed to Damascus and Jordan, respectively.[13] Al-Walid did not personally participate in the campaigns and is reported to have only left Syria once when he led the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca in 710.[1]

Domestic politics

[edit]In stages between 693 and 700, Abd al-Malik and al-Hajjaj initiated the dual processes of issuing a singular Islamic currency in place of the previously used Byzantine and Sassanian models and replacing Greek and Persian with Arabic as the languages of the bureaucracy in Syria and Iraq, respectively.[15][16] These administrative reforms continued under al-Walid, during whose reign, in 705/06, Arabic replaced Greek and Coptic in the dīwān (government registers) of Egypt.[16][17] These policies effected the gradual transition of Arabic as the sole official language of the state, unified the varied tax systems of the caliphate's provinces and contributed to the establishment of a more ideologically Islamic government.[15][18]

As a result of the Battle of Marj Rahit during the inauguration of Marwan's reign in 684, a sharp division developed among the Syrian Arab tribes, who formed the core of the Umayyad army. The loyalist tribes that supported Marwan formed a confederation known as the "Yaman", alluding to ancestral roots in Yemen (South Arabia), while Qaysi tribes largely supported Ibn al-Zubayr. Abd al-Malik reconciled with the Qays in 690, though competition for influence between the two factions intensified as the Syrian army was increasingly empowered and deployed to outside provinces, where they replaced or supplemented Iraqi and other garrisons.[9][19] Al-Walid maintained his father's policy of balancing the power of the two factions in the military and administration.[9] According to historian Hugh N. Kennedy, it is "possible that the caliph kept it [the rivalry] on the boil so that one faction should not acquire a monopoly of power".[9] His mother was genealogically affiliated with the Qays and he apparently accorded Qaysi officials certain advantages.[9] However, other Umayyad princes cultivated strong ties to the Yaman, particularly al-Walid's brother and governor of Palestine, Sulayman, and their cousin and governor of the Hejaz, Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz.[9] The former aligned closely with local Yamani leaders and religious figures, namely Raja ibn Haywah al-Kindi, while Umar maintained his father's network of Yamani loyalists from Egypt and provided refuge for Yamani soldiers persecuted by al-Hajjaj.[9]

Public works and social welfare

[edit]From the beginning of his reign, al-Walid inaugurated a major public works campaign and social welfare programs, both of which were unprecedented in the history of the caliphate.[12] They were financed by war booty collected from the conquests and provincial tax revenues.[12] Public works by the caliph or his brothers and sons during his reign spanned new way-stations and wells along the roads in Syria, street lighting in the cities, land reclamation, while social aid programs included financial relief for the poor and according servants to assist the handicapped.[12]

Al-Walid patronized or encouraged the construction of great mosques throughout the caliphate with special focus paid to his seat of government in Damascus and the Muslim holy cities of Jerusalem, where his father had previously built the Dome of the Rock, and Medina, where the Islamic prophet Muhammad was buried.[20][1] The great mosque al-Walid established in Damascus, later known as the Umayyad Mosque, became one of his greatest architectural achievements. Under his predecessors, Muslim residents had worshiped in a small muṣallā (Muslim prayer room) attached to the 5th-century Church of St. John, but the muṣallā could no longer cope with the fast-growing community and no sufficient free spaces were available elsewhere in Damascus for a large congregational mosque.[21] Thus, in 705, al-Walid had the church converted into a mosque, compensating local Christians with other properties in the city.[21] Most of the structure was demolished with the exceptions of the exterior walls and corner towers, which were thenceforth covered by marble inlays and mosaics.[22] The caliph's architects replaced the demolished space with a large prayer hall and a courtyard bordered on all sides by a closed portico with double arcades.[22] A large cupola was installed at the center of the prayer hall and a high minaret was erected on the mosque's northern wall.[22] The mosque was completed in 711 and Blankinship notes that the field army of Damascus, numbering some 45,000 soldiers, were taxed a quarter of their salaries for nine years to pay for its construction.[12][22] The magnitude and grandeur of the great mosque made it a "symbol of the political supremacy and moral prestige of Islam", according to historian N. Elisséeff.[22]

In Jerusalem, al-Walid continued his father's works on the Haram al-Sharif (Temple Mount).[14] A number of medieval-era Muslim accounts credit the construction of the al-Aqsa Mosque to al-Walid, while others credit his father.[14] However, it is likely that the currently unfinished administrative and residential structures that were built opposite the southern and eastern walls of the Haram, next to the mosque, date to the era of al-Walid, who died before they could be completed and were not finished by his successors.[23] Al-Walid's governor in Medina, Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz, supervised the expansion of the Prophet's Mosque in the city, which included the demolition of the living quarters of Muhammad's wives.[1][24] Al-Walid accorded significant funds to the mosque's reconstruction and supplied Umar with mosaics and Greek craftsmen and laborers.[24] Other mosques that al-Walid is credited for expanding include the Sanctuary Mosque around the Ka'aba in Mecca and the mosque of Ta'if.[12]

Death and legacy

[edit]Al-Walid died in Dayr Murran, an Umayyad winter estate on the outskirts of Damascus,[25] on 25 January or 11 March 715,[26] about a year after al-Hajjaj's death.[11] He was buried in Damascus at the cemetery of Bab al-Saghir or Bab al-Faradis and Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz led the funeral prayers.[25][26] He was survived by sixteen to nineteen sons,[27][note 1] and attempted to nominate his eldest son, Abd al-Aziz, as his successor, voiding the arrangements set by his father, in which Sulayman was to accede after al-Walid.[1] Relations between the two brothers had apparently become strained.[1] However, he was unable to secure this change prior to his death and Sulayman succeeded without opposition.[1]

By virtue of the conquests of Spain, Sindh and Transoxiana launched during his reign, his patronage of the great mosques of Damascus and Medina and his charitable work, al-Walid's Syrian contemporaries viewed him as "the worthiest of their caliphs", according to the report of Umar ibn Shabba (died 878).[25] The Umayyad court poet Jarir (died 728) lamented the caliph's death, proclaiming: "O eye, weep copious tears aroused by remembrance; after today there is no point in your tears being stored."[30] According to Hawting, the reigns of al-Walid and Abd al-Malik, tied together by al-Hajjaj, represented in "some ways the high point of Umayyad power, witnessing significant territorial advances both in the east and the west and the emergence of a more marked Arabic and Islamic character in the state’s public face".[6] It was generally a period of domestic peace and prosperity.[1][9] Kennedy asserts that al-Walid's reign was "remarkably successful and represents, perhaps, the zenith of Umayyad power".[1] However, the caliph's direct role in these successes is unclear and his primary accomplishment may have been maintaining the equilibrium between the rival factions of the Umayyad family and military.[1]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Historian al-Ya'qubi (died 897/98) names sixteen of al-Walid's sons,[27] while historian al-Tabari (died 923) names nineteen.[25] They are the following: Abd al-Aziz and Muhammad, whose mother was Umm al-Banin, a daughter of Abd al-Aziz ibn Marwan; Abu Ubayda, whose mother was from the Banu Fazara tribe;[25] Abd al-Rahman, whose mother was Umm Abd Allah bint Abd Allah ibn Amr, a granddaughter of Caliph Uthman ibn Affan;[28] Yazid III, whose mother, Shah-i Afrid, was the daughter of the last Sassanian king, Peroz III, and a concubine of al-Walid;[29] al-Abbas, Umar, Bishr, Rawh, Khalid, Tammam, Mubashshir, Jurayy, Ibrahim, Yahya, Masrur, Sadaqa, Anbasa and Marwan, all of whom's mothers are not mentioned.[27][25]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Kennedy 2002, p. 127.

- ^ Hinds 1990, p. 118.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 84.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 87.

- ^ a b c Hawting 2000, p. 59.

- ^ a b c d e Dietrich 1971, p. 41.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kennedy 2004, p. 90.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, p. 91.

- ^ a b c d e f Blankinship 1994, p. 82.

- ^ a b Crone 1980, p. 126.

- ^ a b c Bacharach 1996, p. 30.

- ^ a b Gibb 1960, p. 77.

- ^ a b Duri 1965, p. 324.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 38.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Kennedy 2001, p. 34.

- ^ Bacharach 1996, pp. 28, 31, 33–34.

- ^ a b Elisséeff 1965, p. 800.

- ^ a b c d e Elisséeff 1965, p. 801.

- ^ Bacharach 1996, pp. 30, 33.

- ^ a b Bacharach 1996, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d e f Hinds 1990, p. 219.

- ^ a b Biesterfeldt & Günther 2018, p. 1001.

- ^ a b c Biesterfeldt & Günther 2018, pp. 1001–1002.

- ^ Ahmed 2010, p. 123.

- ^ Hillenbrand 1989, p. 234.

- ^ Hinds 1990, p. 220.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ahmed, Asad Q. (2010). The Religious Elite of the Early Islamic Ḥijāz: Five Prosopographical Case Studies. University of Oxford Linacre College Unit for Prosopographical Research. ISBN 9781900934138.

- Bacharach, Jere L. (1996). "Marwanid Umayyad Building Activities: Speculations on Patronage". In Necpoğlu, Gülru (ed.). Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World, Volume 13. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-10633-2.

- Biesterfeldt, Hinrich; Günther, Sebastian (2018). The Works of Ibn Wāḍiḥ al-Yaʿqūbī (Volume 3): An English Translation. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-35621-4.

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihad State: The Reign of Hisham Ibn 'Abd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. Albany: SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-1827-8.

- Crone, Patricia (1980). Slaves on Horses: The Evolution of the Islamic Polity. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52940-9.

- Dietrich, A. (1971). "Al-Ḥadjdjādj b. Yūsuf". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 39–43. OCLC 495469525.

- Duri, A. A. (1965). "Dīwān". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 323–327. OCLC 495469475.

- Elisséeff, N. (1965). "Dimashk". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 277–291. OCLC 495469475.

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1960). "ʿAbd al-Malik b. Marwān". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 76–77. OCLC 495469456.

- Hawting, G. R. (2000). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661–750 (2nd ed.). London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24072-7.

- Hillenbrand, Carole, ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXVI: The Waning of the Umayyad Caliphate: Prelude to Revolution, A.D. 738–744/A.H. 121–126. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-810-2.

- Hinds, Martin, ed. (1990). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXIII: The Zenith of the Marwānid House: The Last Years of ʿAbd al-Malik and the Caliphate of al-Walīd, A.D. 700–715/A.H. 81–95. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-721-1.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25092-7.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2002). "Al-Walīd (I)". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume XI: W–Z. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-90-04-12756-2.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Ltd. ISBN 0-582-40525-4.

- Wellhausen, J. (1927). Weir, Margaret Graham (ed.). The Arab Kingdom and its Fall. University of Calcutta. ISBN 9780415209045.