User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles

Prehistory articles 1

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/1

The Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event was the mass extinction of three-quarters of Earth's plant and animal species during a geologically brief interval about 66 million years (Ma) ago. A wide range of species perished in the K–Pg extinction, most notably the non-avian dinosaurs. However, other groups that sustained losses or vanished include mammals, pterosaurs, birds, lizards, insects, and plants. In the oceans, the K–Pg extinction devastated the giant marine lizards, plesiosaurs, fishes, ammonites and plankton. It marked the end of the Cretaceous period and with it, the entire Mesozoic Era, opening the Cenozoic Era which continues today.In the geologic record, the K–Pg event is marked by a thin layer of sediment called the K–Pg boundary, which can be found throughout the world in marine and terrestrial rocks. The boundary clay shows high levels of the metal iridium, which is rare in the Earth's crust but abundant in asteroids. It is now generally believed that the K–Pg extinction was triggered by a massive comet/asteroid impact and its catastrophic effects on the global environment, including a lingering impact winter that halted photosynthesis in plants and plankton. However, some scientists maintain the extinction was caused or exacerbated by other factors, such as volcanic eruptions, climate change, and/or sea level change. Whatever the cause, many of the surviving animal groups diversified during the ensuing Paleogene period. Mammals in particular radiated into new forms such as horses, whales, bats, and primates. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 2

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/2

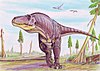

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of animals that first appeared during the Triassic period, 231.4 million years ago, and were the dominant terrestrial vertebrates for 135 million years, from the beginning of the Jurassic until the end of the Cretaceous (66 million years ago), when the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event led to the extinction of most dinosaur groups. The fossil record indicates that birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs and, consequently, they are considered a subgroup of dinosaurs by many paleontologists. Some birds survived the extinction event and their descendants continue the dinosaur lineage to the present day.Using fossil evidence, paleontologists have identified over 500 distinct genera of non-avian dinosaurs. Dinosaurs are represented on every continent. Some are herbivorous, others carnivorous. While dinosaurs were ancestrally bipedal, many extinct groups included quadrupedal species. Elaborate display structures such as horns or crests are common to all dinosaur groups, and some extinct groups developed skeletal modifications such as bony armor and spines. Evidence suggests that egg laying and nest building are additional traits shared by all dinosaurs. While modern birds are generally small due to the constraints of flight, many prehistoric dinosaurs were large-bodied—the largest sauropod dinosaurs may have achieved lengths of 58 meters (190 feet). Many dinosaurs were quite small: Xixianykus, for example, was only about 50 cm (20 in) long. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 3

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/3

The Ediacara biota consisted of enigmatic tubular and frond-shaped, mostly sessile organisms that lived during the Ediacaran Period (ca. 635–542 Ma). Trace fossils of these organisms have been found worldwide, and represent the earliest known complex multicellular organisms. The Ediacara biota radiated in an event called the Avalon explosion, 575 million years ago, after the Earth had thawed from the Cryogenian period's extensive glaciation. The biota largely disappeared contemporaneously with the rapid increase in biodiversity known as the Cambrian explosion. Most of the currently existing body plans of animals first appeared in the fossil record of the Cambrian rather than the Ediacaran. For macroorganisms, the Cambrian biota appears to have completely replaced the organisms that populated the Ediacaran fossil record, although relationships are still a matter of debate.Multiple hypotheses exist to explain the disappearance of this biota, including preservation bias, a changing environment, the advent of predators and competition from other life-forms. Breandán MacGabhann argues that the concept of "Ediacara Biota" is artificial and arbitrary as it can not be defined geographically, stratigraphically, taphonomically nor biologically. He points out that 8 particular fossils or groups of fossils considered "Ediacaran" have 5 taphonomic modes (preservation styles), occur in 3 geological periods, and have no phylogenetic meaning as a whole. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 4

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/4

Paraceratherium is an extinct genus of hornless rhinoceros, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals that has ever existed. It lived from the early to late Oligocene epoch (34–23 million years ago); its remains have been found across Eurasia between China and the former Yugoslavia. Paraceratherium is classified as a member of the hyracodont subfamily Indricotheriinae. Paraceratherium means "near the hornless beast", in reference to Aceratherium, a genus that was once thought similar.The exact size of Paraceratherium is unknown because of the incompleteness of the fossils. Its weight is estimated to have been 15 to 20 tonnes (33,000 to 44,000 lb) at most; the shoulder height was about 4.8 metres (16 feet), and the length about 7.40 metres (24.3 feet). The legs were long and pillar-like. The long neck supported a skull that was about 1.3 metres (4.3 ft) long. It had large, tusk-like incisors and a nasal incision that suggests it had a prehensile upper lip or proboscis. The lifestyle of Paraceratherium may have been similar to that of modern large mammals such as the elephants and extant rhinoceroses. Because of its size, it would have had few predators and a slow rate of reproduction. Paraceratherium was a browser, eating mainly leaves, soft plants, and shrubs. It lived in habitats ranging from arid deserts with a few scattered trees to subtropical forests. The reasons for the animal's extinction are unknown, but various factors have been proposed. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 5

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/5

Psittacosaurus (/ˌsɪtəkəˈsɔːrəs/ SIT-ə-kə-SOR-əs; from the Greek for "parrot lizard") is a genus of psittacosaurid ceratopsian dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous Period of what is now Asia, between 124.2 to 100 million years ago. It is notable for being the most species-rich dinosaur genus. Nine to eleven species are recognized from fossils found in different regions of modern-day China, Mongolia and Russia, with a possible additional species from Thailand.All species of Psittacosaurus were gazelle-sized bipedal herbivores characterized by a high, powerful beak on the upper jaw. At least one species had long, quill-like structures on its tail and lower back, possibly serving a display function. Psittacosaurs were extremely early ceratopsians. Although they developed many novel adaptations, they shared many anatomical features with later ceratopsians such as Protoceratops and Triceratops.

Psittacosaurus is not as familiar to the general public as its distant relative Triceratops but it is one of the most completely known dinosaur genera. Fossils of over 400 individuals have been collected so far, including many complete skeletons. Most different age classes are represented, from hatchling through to adult, which has allowed several detailed studies of Psittacosaurus growth rates and reproductive biology. The abundance of this dinosaur in the fossil record has led to the creation of the Psittacosaurus biochron for Lower Cretaceous sediments of east Asia. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 6

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/6

Tarbosaurus is a genus of tyrannosaurid theropod dinosaur that flourished in Asia about 70 million years ago, at the end of the Late Cretaceous Period. Fossils have been recovered in Mongolia, with more fragmentary remains found further afield in parts of China.Although many species have been named, modern paleontologists recognize only one, T. bataar, as valid. Some experts see this species as an Asian representative of the North American genus Tyrannosaurus; this would make the genus Tarbosaurus redundant. Tarbosaurus and Tyrannosaurus, if not synonymous, are considered to be at least closely related genera.

Like most known tyrannosaurids, Tarbosaurus was a large bipedal predator, weighing up to six tonnes and equipped with about sixty large teeth. It had a unique locking mechanism in its lower jaw and the smallest forelimbs relative to body size of all tyrannosaurids, renowned for their disproportionately tiny, two-fingered forelimbs.

Tarbosaurus lived in a humid floodplain criss-crossed by river channels. In this environment, it was an apex predator at the top of the food chain, probably preying on other large dinosaurs like the hadrosaur Saurolophus or the sauropod Nemegtosaurus. Tarbosaurus is very well represented in the fossil record, known from dozens of specimens, including several complete skulls and skeletons. These remains have allowed scientific studies focusing on its phylogeny, skull mechanics, and brain structure. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 7

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/7

Velociraptor is a genus of dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaur that lived approximately 75 to 71 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous Epoch. Two species are currently recognized, although others have been assigned in the past. The type species is V. mongoliensis; fossils of this species have been discovered in Mongolia. A second species, V. osmolskae, was named in 2008 for skull material from Inner Mongolia, China.Like other dromaeosaurids like Deinonychus and Achillobator, Velociraptor was a bipedal, feathered carnivore with a long tail and an enlarged sickle-shaped claw on each hindfoot, which is thought to have been used to tackle prey. Velociraptor can be distinguished from other dromaeosaurids by its long and low skull, with an upturned snout.

Velociraptor (commonly shortened to "raptor") is one of the dinosaur genera most familiar to the general public due to its prominent role in the Jurassic Park motion picture series. In the films it was shown with anatomical inaccuracies, including being much larger than it was in reality and without feathers. Some of these inaccuracies, along with the head's larger dome in the movies may suggest that the dinosaurs in the movies were actually modeled on Deinonychus. Velociraptor is also well known to paleontologists, with over a dozen described fossil skeletons, the most of any dromaeosaurid. One particularly famous specimen preserves a Velociraptor locked in combat with a Protoceratops. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 8

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/8

The woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) was a species of mammoth, the common name for the extinct elephant genus Mammuthus. Its closest extant relative is the Asian elephant. The appearance and behaviour of this species are among the best studied of any prehistoric animal because of the discovery of frozen carcasses in Siberia and Alaska, as well as skeletons, teeth, stomach contents, dung, and depiction from life in prehistoric cave paintings. The mammoth was identified as an extinct species of elephant by Georges Cuvier in 1796.The woolly mammoth was roughly the same size as modern African elephants. Males reached shoulder heights between 2.7 and 3.4 m (9 and 11 ft) and weighed up to 6 tonnes (6.6 short tons). Females averaged 2.6–2.9 metres (8.5–9.5 ft) in height and weighed up to 4 tonnes (4.4 short tons). The woolly mammoth was well adapted to the cold environment during the last ice age. It was covered in fur, with an outer covering of long guard hairs and a shorter undercoat. The colour of the coat varied from dark to light. The ears and tail were short to minimise frostbite and heat loss. It had long, curved tusks and four molars, which were replaced six times during the lifetime of an individual. The diet of the woolly mammoth was mainly grass and sedges. Its habitat was the mammoth steppe, which stretched across northern Eurasia and North America. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 9

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/9

The list of dinosaurs is a comprehensive listing of all genera that have ever been included in the superorder Dinosauria, excluding class Aves (birds, both living and those known only from fossils) and purely vernacular terms. The list includes all commonly accepted genera, but also genera that are now considered invalid, doubtful (nomen dubium), or were not formally published (nomen nudum), as well as junior synonyms of more established names, and genera that are no longer considered dinosaurs. Many listed names have been reclassified as everything from birds to crocodilians to petrified wood. The list contains more than 1,000 names considered either valid dinosaur genera or nomina dubia. (see more...)Prehistory articles 10

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/10

Funerary art is any work of art forming, or placed in, a repository for the remains of the dead. The term also encompasses cenotaphs ("empty tombs"), tomb-like monuments which do not contain human remains; and communal memorials to the dead (such as war memorials), which may or may not contain human remains.Funerary art may serve many cultural functions. It can play a role in burial rites, serve as an article for use by the dead in the afterlife, and celebrate the life and accomplishments of the dead, whether as part of kinship-centred practices of ancestor veneration or as a publicly directed dynastic display. It can also function as a reminder of the mortality of humankind, as an expression of cultural values and roles, and help to propitiate the spirits of the dead, maintaining their benevolence and preventing their unwelcome intrusion into the affairs of the living.

The deposit of objects with an apparent aesthetic intention may go back to the Neanderthals over 50,000 years ago,[1] and is found in almost all subsequent cultures—Hindu culture, which has little, is a notable exception. Many of the best-known artistic creations of past cultures—from the Egyptian pyramids and the Tutankhamun treasure to the Terracotta Army surrounding the tomb of the Qin Emperor, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, the Sutton Hoo ship burial and the Taj Mahal—are tombs or objects found in and around them. In most instances, specialized funeral art was produced for the powerful and wealthy, although the burials of ordinary people might include simple monuments and grave goods, usually from their possessions.

An important factor in the development of traditions of funerary art is the division between what was intended to be visible to visitors or the public after completion of the funeral ceremonies.[2] The Tutankhamun treasure, for example, though exceptionally lavish, was never intended to be seen again after it was deposited, while the exterior of the pyramids was a permanent and highly effective demonstration of the power of their creators. A similar division can be seen in grand East Asian tombs. In other cultures, nearly all the art connected with the burial, except for limited grave goods, was intended for later viewing by the public or at least those admitted by the custodians. In these cultures, traditions such as the sculpted sarcophagus and tomb monument of the Greek and Roman empires, and later the Christian world, have flourished. The mausoleum intended for visiting was the grandest type of tomb in the classical world, and later common in Islamic culture. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 11

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/11

Homo floresiensis ("Flores Man"; nicknamed "hobbit" and "Flo") is an extinct species widely believed to be in the genus Homo. The remains of an individual that would have stood about 3.5 feet (1.1 m) in height were discovered in 2003 on the island of Flores in Indonesia. Partial skeletons of nine individuals have been recovered, including one complete skull, referred to as "LB1".[3][4] These remains have been the subject of intense research to determine whether they represent a species distinct from modern humans. This hominin is remarkable for its small body and brain and for its survival until relatively recent times (possibly as recently as 12,000 years ago).[5] Recovered alongside the skeletal remains were stone tools from archaeological horizons ranging from 94,000 to 13,000 years ago. Some scholars suggest that the historical H. floresiensis may be connected by folk memory to ebu gogo myths prevalent on the isle of Flores.[6]The discoverers (archaeologist Mike Morwood and colleagues) proposed that a variety of features, both primitive and derived, identify these individuals as belonging to a new species, H. floresiensis, within the taxonomic tribe of Hominini, which includes all species that are more closely related to humans than to chimpanzees.[3][5] The discoverers also proposed that H. floresiensis lived contemporaneously with modern humans on Flores.[7]

Doubts that the remains constitute a new species were soon voiced by the Indonesian anthropologist Teuku Jacob, who suggested that the skull of LB1 was a microcephalic modern human. Two studies by paleoneurologist Dean Falk and her colleagues (2005, 2007) rejected this possibility.[8][9][10] Falk et al. (2005) has been rejected by Martin et al. (2006) and Jacob et al. (2006), but defended by Morwood (2005) and Argue, Donlon et al. (2006).

Two orthopedic researches published in 2007 reported evidence to support species status for H. floresiensis. A study of three tokens of carpal (wrist) bones concluded there were similarities to the carpal bones of a chimpanzee or an early hominin such as Australopithecus and also differences from the bones of modern humans.[11][12] A study of the bones and joints of the arm, shoulder, and lower limbs also concluded that H. floresiensis was more similar to early humans and apes than modern humans.[13][14] In 2009, the publication of a cladistic analysis[15] and a study of comparative body measurements[16] provided further support for the hypothesis that H. floresiensis and Homo sapiens are separate species.

Critics of the claim for species status continue to believe that these individuals are Homo sapiens possessing pathologies of anatomy and physiology. Several hypotheses in this category have been put forward, including that the individuals were born without a functioning thyroid, resulting in a type of endemic cretinism (myxoedematous, ME),[17] and that the principal specimen LB1 suffered from Down syndrome.[18][19] (see more...)

Prehistory articles 12

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/12

Aetosaurs (order name Aetosauria) are an extinct order of heavily armoured, medium- to large-sized Late Triassic herbivorous archosaurs. They have small heads, upturned snouts, erect limbs, and a body covered by plate-like scutes. All aetosaurs belong to the family Stagonolepididae. Two distinct subdivisions of aeotosaurs are currently recognized, Desmatosuchinae and Aetosaurinae, based primarily on differences in the morphology of the bony scutes of the two groups. Over 20 genera of aetosaurs have been described.Aetosaur fossil remains are known from Europe, North and South America, parts of Africa and India. Since their armoured plates are often preserved and are abundant in certain localities, aetosaurs serve as important Late Triassic tetrapod index fossils. Many aetosaurs had wide geographic ranges, but their stratigraphic ranges were relatively short. Therefore, the presence of particular aetosaurs can accurately date a site that they are found in.

Aetosaur remains have been found since the early 19th century, although the very first remains that were described were mistaken for fish scales. Aetosaurs were later recognized as crocodile relatives, with early paleontologists considering them to be semiaquatic scavengers. They are now considered to have been entirely terrestrial animals. Some forms have characteristics that may have been adaptations to digging for food. There is also evidence that some if not all aetosaurs made nests. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 13

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/13

Afrasia djijidae is a fossil primate that lived in Myanmar approximately 37 million years ago, during the late middle Eocene. The only species in the genus Afrasia, it was a small primate, estimated to weigh around 100 grams (3.5 oz). Despite the significant geographic distance between them, Afrasia is thought to be closely related to Afrotarsius, an enigmatic fossil found in Libya and Egypt that dates to 38–39 million years ago. If this relationship is correct, it suggests that early simians (a related group or clade consisting of monkeys, apes, and humans) dispersed from Asia to Africa during the middle Eocene and would add further support to the hypothesis that the first simians evolved in Asia, not Africa. Neither Afrasia nor Afrotarsius, which together form the family Afrotarsiidae, is considered ancestral to living simians, but they are part of a side branch or stem group known as eosimiiforms.Afrasia is known from four isolated molar teeth found in the Pondaung Formation of Myanmar. These teeth are similar to those of Afrotarsius and Eosimiidae, and differ only in details of the chewing surface. For example, the back part of the third lower molar is relatively well-developed. In the Pondaung Formation, Afrasia was part of a diverse primate community that also includes the eosimiid Bahinia and members of the families Amphipithecidae and Sivaladapidae. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 14

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/14

Archaeamphora longicervia is an extinct species of flowering plant and the only member of the genus Archaeamphora. Fossil material assigned to this taxon originates from the Yixian Formation of northeastern China, dated to the Early Cretaceous (around 145 to 101 million years ago).The species was originally described as a pitcher plant with close affinities to extant members of the family Sarraceniaceae. This would make it the earliest known carnivorous plant and the only known fossil record of pitcher plants (with the possible exception of some palynomorphs of uncertain nepenthacean affinity).Archaeamphora is also one of the three oldest known genera of angiosperms (flowering plants). Li (2005) wrote that "the existence of a so highly derived Angiosperm in the Early Cretaceous suggests that Angiosperms should have originated much earlier, maybe back to 280 mya as the molecular clock studies suggested".

Subsequent authors have questioned the identification of Archaeamphora as a pitcher plant. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 15

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/15

Chitinozoa (singular: chitinozoan, plural: chitinozoans) are a taxon of flask-shaped, organic walled marine microfossils produced by an as yet unknown animal. Common from the Ordovician to Devonian periods (i.e. the mid-Paleozoic), the millimetre-scale organisms are abundant in almost all types of marine sediment across the globe. This wide distribution, and their rapid pace of evolution, makes them valuable biostratigraphic markers.Their bizarre form has made classification and ecological reconstruction difficult. Since their discovery in 1931, suggestions of protist, plant, and fungalaffinities have all been entertained. The organisms have been better understood as improvements in microscopy facilitated the study of their fine structure, and there is mounting evidence to suggest that they represent either the eggs or juvenile stage of a marine animal.

The ecology of chitinozoa is also open to speculation; some may have floated in the water column, where others may have attached themselves to other organisms. Most species were particular about their living conditions, and tend to be most common in specific paleoenvironments. Their abundance also varied with the seasons.(see more...)

Prehistory articles 16

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/16

The Cloudinids, an early metazoan family containing the genus Cloudina, lived in the late Ediacaran period and became extinct at the base of the Cambrian. They formed millimetre-scale conical fossils consisting of calcareous cones nested within one another; the appearance of the organism itself remains unknown. Current scientific opinion is divided between classifying them as polychaetes and regarding it as unsafe to classify them as members of any broader grouping.Cloudinids had a wide geographic range, reflected in the present distribution of localities in which their fossils are found, and are an abundant component of some deposits. They never appear in the same layers as soft-bodied Ediacaran biota, but the fact that some sequences contain Cloudinids and Ediacaran biota in alternating layers suggests that these groups had different environmental preferences.

Cloudinids are important in the history of animal evolution for two reasons. They are among the earliest and most abundant of the small shelly fossils with mineralized skeletons, and therefore feature in the debate about why such skeletons first appeared in the Late Ediacaran. The most widely-supported answer is that their shells are a defense against predators, as some Cloudina specimens from China bear the marks of multiple attacks, which suggests they survived at least a few of them. The evolutionary arms race which this indicates is commonly cited as a cause of the Cambrian explosion of animal diversity and complexity. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 17

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/17

A coal ball is a type of concretion that is found in coal and consists of plant debris (peat), which has been permineralised by calcite. Coal balls vary in shape from imperfectly spherical to flat-lying, irregular slabs. These concretions formed by the early permineralisation of peat by calcite in Carboniferous Period swamps and mires prior to its alteration to coal. They derive their name from their association with coal and their often imperfectly spherical shape. Because they formed in prehistoric peats prior to them becomingcoalified, they often preserve remarkable record of the tissue structure of Carboniferous swamp and mire plants. Paleontologists have to cut and cut and peel open the coal balls to extract the fossils inside.In 1855, two English scientists, Joseph Dalton Hooker and Edward William Binney, made the first scientific description of coal balls in England, and the initial research on coal balls was carried out in Europe. North American Coal balls were later discovered and identified in 1922. Since then, coal balls have been found in other countries, and they have led to the discovery of hundreds of species and genera.

Coal balls may be found in coal seams across North America and Eurasia. North American coal balls are relatively widespread, both stratigraphically and geologically, as compared to coal balls from Europe. The oldest known coal balls date from the Namurian stage of the Carboniferous, and they were found in Germany and on the territory of former Czechoslovakia. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 18

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/18

Java Man (Homo erectus erectus) is the popular name given to early human fossils discovered on the island of Java (Indonesia) in 1891 and 1892. Led by Eugène Dubois, the excavation team uncovered a tooth, a skullcap, and a thighbone at Trinil on the banks of the Solo River in East Java. Arguing that the fossils represented the "missing link" between apes and humans, Dubois gave the species the scientific name Anthropopithecus erectus, then later renamed it Pithecanthropus erectus.The fossil aroused much controversy. Less than ten years after 1891, almost eighty books or articles had been published on Dubois's finds. Despite Dubois' argument, few accepted that Java Man was a transitional form between apes and humans. Some dismissed the fossils as apes and others as modern humans, whereas many scientists considered Java Man as a primitive side branch of evolution not related to modern humans at all.

Eventually, similarities between Pithecanthropus erectus (Java Man) and Sinanthropus pekinensis (Peking Man) led Ernst Mayr to rename both Homo erectus in 1950, placing them directly in the human evolutionary tree. To distinguish Java Man from other Homo erectus populations, some scientists began to regard it as a subspecies, Homo erectus erectus, in the 1970s. Estimated to be between 700,000 and 1,000,000 years old, at the time of their discovery the fossils of Java Man were the oldest hominin fossils ever found. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 19

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/19

Megalodon (/ˈmɛɡələdɒn/ MEG-ə-lə-don; meaning "big tooth", from Ancient Greek: μέγας, romanized: (megas), lit. 'big, mighty' and ὀδoύς (odoús), "tooth"—whose stem is odont-, as seen in the genitive case form ὀδόντος, odóntos) is an extinct species of shark that lived approximately 15.9 to 2.6 million years ago, during the Cenozoic Era (middle Miocene to end of Pliocene).The taxonomic assignment of C. megalodon has been debated for nearly a century, and is still under dispute. The two major interpretations are Carcharodon megalodon (under family Lamnidae) or Carcharocles megalodon (under the family Otodontidae). Consequently, the scientific name of this species is commonly abbreviated C. megalodon in the literature.

C. megalodon is regarded as one of the largest and most powerful predators in vertebrate history, and likely had a profound impact on the structure of marine communities. Fossil remains suggest that this giant shark reached a maximum length of 18 metres (59 ft), and also affirm that it had a cosmopolitan distribution. Scientists suggest that C. megalodon looked like a stockier version of the great white shark, Carcharodon carcharias. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 20

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/20

Passer predomesticus is a fossil passerine bird in the sparrow family Passeridae. First described in 1962, it is known from two premaxillary (upper jaw) bones found in a Middle Pleistocene layer of the Oumm-Qatafa cave in Palestine. The premaxillaries resemble those of the house and Spanish sparrows, but differ in having a deep groove instead of a crest on the lower side. Israeli palaeontologist Eitan Tchernov, who described the species, and others have considered it to be close to the ancestor of the house and Spanish sparrows, but molecular data point to an earlier origin of modern sparrow species. Occurring in a climate Tchernov described as similar to but rainier than that in Palestine today, it was considered by Tchernov as a "wild" ancestor of the modern sparrows which have a commensal association with humans, although its presence in Oumm-Qatafa cave may indicate that it was associated with humans. (see more...)Prehistory articles 21

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/21

Pterosaurs were flying reptiles of the clade or order Pterosauria. They existed from the late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous Period (228 to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earliest vertebrates known to have evolved powered flight. Their wings were formed by a membrane of skin, muscle, and other tissues stretching from the ankles to a dramatically lengthened fourth finger. Early species had long, fully toothed jaws and long tails, while later forms had a highly reduced tail, and some lacked teeth. Many sported furry coats made up of hair-like filaments known as pycnofibres, which covered their bodies and parts of their wings. Pterosaurs spanned a wide range of adult sizes, from the very small Nemicolopterus to the largest known flying creatures of all time, including Quetzalcoatlus and Hatzegopteryx.Pterosaurs are often referred to in the popular media and by the general public as flying dinosaurs, but this is incorrect. However, like the dinosaurs, pterosaurs are more closely related to birds than to any living reptile. Pterosaurs are also incorrectly referred to as pterodactyls, particularly by journalists. "Pterodactyl" refers specifically to members of the genus Pterodactylus, and more broadly to members of the suborder Pterodactyloidea of the pterosaurs. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 22

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/22

Saadanius is a genus of fossil primate dating to the Oligocene that is closely related to the common ancestor of the Old World monkeys and apes, collectively known as catarrhines. It is represented by a single species, Saadanius hijazensis, which is known only from a single partial skull tentatively dated between 29 and 28 mya (million years ago). It was discovered in 2009 in western Saudi Arabia near Mecca and was first described in 2010 after a comparison with both living and fossil catarrhines.Saadanius had a longer face than living catarrhines and lacked the advanced frontal sinus (airspaces in the facial bones) found in living catarrhines. However, it had a bony ear tube (ectotympanic) and teeth comparable to those of living catarrhines. The discovery of Saadanius may help answer questions about the evolution and appearance of the last common ancestors of Old World monkeys and apes. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 23

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/23

The small shelly fauna or small shelly fossils, abbreviated to SSF, are mineralized fossils, many only a few millimetres long, with a nearly continuous record from the latest stages of the Ediacaran to the end of the Early Cambrian period. They are very diverse, and there is no formal definition of "small shelly fauna" or "small shelly fossils". Almost all are from earlier rocks than more familiar fossils such as trilobites. Since most SSFs were preserved by being covered quickly with phosphate and this method of preservation is mainly limited to the Late Ediacaran and Early Cambrian periods, the animals that made them may actually have arisen earlier and persisted after this time span.The bulk of the fossils are fragments or disarticulated remains of larger organisms, including sponges, molluscs, slug-like halkieriids, brachiopods, echinoderms, and onychophoran-like organisms that may have been close to the ancestors of arthropods. Although the small size and often fragmentary nature of SSFs makes it difficult to identify and classify them, they provide very important evidence for how the main groups of marine invertebrates evolved, and particularly for the pace and pattern of evolution in the Cambrian explosion. Besides including the earliest known representatives of some modern phyla, they have the great advantage of presenting a nearly continuous record of Early Cambrian organisms whose bodies include hard parts. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 24

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/24

The Temnospondyli are a diverse order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered primitive amphibians—that flourished worldwide during the Carboniferous, Permian, and Triassic periods. A few species continued into the Cretaceous. Fossils have been found on every continent. During about 210 million years of evolutionary history, they adapted to a wide range of habitats, including fresh water, terrestrial, and even coastal marine environments. Their life history is well understood, with fossils known from the larval stage, metamorphosis, and maturity. Most temnospondyls were semiaquatic, although some were almost fully terrestrial, returning to the water only to breed. These temnospondyls were some of the first vertebrates fully adapted to life on land. Although temnospondyls are considered amphibians, many had characteristics, such as scales, claws, and armor-like bony plates, that distinguish them from modern amphibians.Authorities disagree over whether temnospondyls were ancestral to modern amphibians (frogs, salamanders, and caecilians), or whether the whole group died out without leaving any descendants. Different hypotheses have placed modern amphibians as the descendants of temnospondyls, another group of early tetrapods called lepospondyls, or even as descendants of both groups (with caecilians evolving from lepospondyls and frogs and salamanders evolving from temnospondyls). Recent studies place a family of temnosondyls called the amphibamids as the closest relatives of modern amphibians. Similarities in teeth, skulls, and hearing structures link the two groups. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 25

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/25

Opisthocoelicaudia /ɒˌpɪsθoʊsɪlɪˈkɔːdiə/ was a genus of sauropod dinosaur of the Late Cretaceous Period discovered in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia. The only species is Opisthocoelicaudia skarzynskii. A well-preserved skeleton lacking only the head and neck was unearthed in 1965 by Polish and Mongolian scientists, making Opisthocoelicaudia one of the best known sauropods from the Late Cretaceous. Tooth marks on this skeleton indicate that large carnivorous dinosaurs had fed on the carcass and possibly had carried away the now-missing parts. A relatively small sauropod, Opisthocoelicaudia measured approximately 11 metres (36 ft) in length. The name Opisthocoelicaudia means "posterior cavity tail", alluding to the unusual, opisthocoel condition of the anterior tail vertebrae that were concave on their posterior sides. This and other skeletal features lead researchers to propose that Opisthocoelicaudia was able to rear on its hindlegs.Named and described by Polish paleontologist Maria Magdalena Borsuk-Białynicka in 1977, Opisthocoelicaudia was first thought to be a new member of the Camarasauridae, but is currently considered a derived member of the Titanosauria. Its exact relationships within Titanosauria are contentious, but it may have been close to the North American Alamosaurus. All Opisthocoelicaudia fossils stem from the Nemegt Formation. (see more...)

Prehistory articles 26

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/26

Ypresiomyrma is an extinct genus of ants in the subfamily Myrmeciinae that was described in 2006. There are four species described; one species is from the Isle of Fur in Denmark, two are from the McAbee Fossil Beds in British Columbia, Canada, and the fourth from the Bol’shaya Svetlovodnaya fossil site in Russia. The queens of this genus are large, the mandibles are elongated and the eyes are well developed; a stinger is also present. The behaviour of these ants would have been similar to that of extant Myrmeciinae ants, such as solitary foraging for arthropod prey and never leaving pheromone trails. The alates were poor flyers due to their size, and birds and animals most likely preyed on these ants. Ypresiomyrma is not assigned to any tribe, and is instead generally regarded as incertae sedis within Myrmeciinae. However, some authors believe Ypresiomyrma should be assigned as incertae sedis within Formicidae. (see more...)Prehistory articles 27

User:Abyssal/Prehistory of Asia/Prehistory articles/27

Bharattherium molariforms are high, curved teeth, with a height of 6 to 8.5 millimetres (0.24 to 0.33 in). In a number of teeth tentatively identified as fourth lower molariforms (mf4), there is a large furrow on one side and a deep cavity (infundibulum) in the middle of the tooth. Another tooth, perhaps a third lower molariform, has two furrows on one side and three infundibula on the other. The tooth enamel has traits that have been interpreted as protecting against cracks in the teeth. The hypsodont (high-crowned) teeth of sudamericids like Bharattherium are reminiscent of later grazing mammals, and the discovery of grass in Indian fossil sites contemporaneous with those yielding Bharattherium suggest that sudamericids were indeed grazers. (see more...)

- ^ Depending on the interpretation of sites like the Shanidar Cave in Iraq. Bogucki, 64–66 summarizes the debate. Gargett takes a hostile view but accepts (p. 29 etc.) that many or most scholars do not. See also Pettitt.

- ^ See for example the chapter "Tombs for the Living and the Dead", Insoll 176–87.

- ^ a b Brown et al. 2004

- ^ Morwood, Brown et al. 2005

- ^ a b Morwood, Soejono et al. 2004

- ^ Gregory Forth, Hominids, hairy hominoids and the science of humanity, Anthropology Today, Vol. 21 No. 3 (June 2005), pp. 13-17; John D. Hawks, Stalking the wild ebu gogo (June 24, 2005).

- ^ McKie, Robin (February 21, 2010). "How a hobbit is rewriting the history of the human race". The Guardian. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- ^ Falk et al. 2005

- ^ Falk et al. 2007

- ^ FSU News 2007

- ^ Tocheri et al. 2007

- ^ New Scientist 2007-09-20

- ^ Larson et al. 2007 (preprint online)

- ^ Guardian 2007-09-21

- ^ Argue, Morwood et al. 2009

- ^ Jungers and Baab 2009

- ^ Obendorf et al. 2008

- ^ "Did the 'Hobbit' have Down syndrome?".

- ^ ""Hobbit" Specimen Likely Down Syndrome - The Skeptics Guide to the Universe".