University of Louisville School of Law

This article has an unclear citation style. (February 2016) |

| University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law | |

|---|---|

| |

| Parent school | University of Louisville |

| Established | 1846 |

| School type | Public |

| Parent endowment | |

| Dean | Melanie Jacobs |

| Location | Louisville, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Enrollment | 355 [citation needed] |

| USNWR ranking | 99th (2023)[1] |

| Website | louisville |

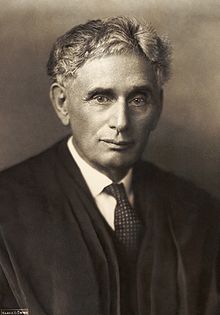

The University of Louisville Louis D. Brandeis School of Law, commonly referred to as The University of Louisville School of Law[2][3] or the Brandeis School of Law,[4] is the law school of the University of Louisville. Established in 1846, it is the oldest law school in Kentucky and the fifth oldest in the country in continuous operation.[5] The law school is named after Justice Louis Dembitz Brandeis, who served on the Supreme Court of the United States and was the school's patron. Following the example of Brandeis, who eventually stopped accepting payment for "public interest" cases,[6] Louis D. Brandeis School of Law was one of the first law schools in the nation to require students to complete public service before graduation.[7]

The school offers six dual-degree programs that allow students to earn an MBA, MSW, MA in humanities, M.Div. (with the Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary), MA in political science, and MUP in urban planning while attaining their J.D. These classes are offered in conjunction with other University of Louisville departments.

The school's law library contains 400,000 volumes as well as the papers of Louis D. Brandeis and John Marshall Harlan, both Supreme Court Justices and native Kentuckians. It is one of only thirteen Supreme Court repositories in the nation. The law school's flagship law review is the University of Louisville Law Review.[8]

According to University of Louisville's 2018 ABA-required disclosures, 92% of the Class of 2018 was employed within ten months of graduation. This includes 76% who obtained full-time, long-term, JD-required employment ten months after graduation, excluding solo practitioners.[9]

History

[edit]19th and early 20th century history

[edit]

Louis D. Brandeis School of Law began in 1846 as the Law Department of the University of Louisville. For most of the nineteenth century the Law Department remained small and focused on practical education. "As late as the 1870s the school still supported a faculty of only three professors, each of whom met classes two days per week for four hours."[10] Classes were held in the late afternoon to allow students to keep daytime jobs as law clerks. The faculty ignored the casebook method of instruction that was being developed at Harvard Law School at the time, instead encouraging students to visit local courts and offering optional mock court sessions. The "school literature even boasted that the faculty consisted of 'practical lawyers' and not professional educators."[10] As a result, prominent faculty members such as James Speed and Peter B. Muir often eschewed their part-time positions in favor of politics or private practice.

The turn of the twentieth century saw the Law Department finally begin to accept emerging national standards in legal education. In 1909, the school adopted Harvard Law's casebook method. In 1911, the school graduated its first female student, N. Almee Courtright. In 1923, the Law Department officially became the School of Law and hired a full-time professor. The following year University of Louisville President Arthur Younger Ford insisted that students must take some college courses before being admitted to the law school.[10]

The UofL School of Law and the Jefferson School of Law

[edit]Despite these efforts at reform, the students and professors of the School of Law continued to prefer part-time practical education over the national trend towards more formal legal education. This partly reflected the success of and competition from the Jefferson School of Law, which opened in 1905 and offered night classes.[citation needed]

Organized by several prominent local attorneys, the part-time professors at the Jefferson School of Law received tuition directly from the students and were responsible for renting classroom space. With students wishing to clerk and part-time professors continuing to practice, both schools were located within walking distance of the courthouse. As the national trend continued towards formal legal education, the Jefferson School of Law found it difficult to manage as a part-time law school. In 1950 the Jefferson School of Law merged with the University of Louisville School of Law.[10]

Louis D. Brandeis and the UofL School of Law

[edit]Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis was a great supporter of the University of Louisville. A native Louisvillian, Brandeis planned to make the university a "major center of academic research by creating specialized library and archival collections in such areas as sociology, art, music, and labor."[10] In addition to time and money, Brandeis also donated his personal papers, books, and pamphlets, numbering over 250,000 items. He was also instrumental in getting Supreme Court briefs and a collection of Justice John Marshall Harlan's papers deposited in the law school library.[11]

In honor of Brandeis, the University of Louisville School of Law changed its name to the Louis D. Brandeis School of Law in 1997.[citation needed]

The school's Louis D. Brandeis Society, established in 1976, awards the Brandeis Medal to individuals whose lives reflect Louis Brandeis' commitment to the ideals of individual liberty, concern for the disadvantaged and public service.

The Brandeis Law Library owns a limited edition print of Andy Warhol's portrait of Brandeis which is on display in the library's main reading room.[12]

The ashes of Brandeis and his wife Alice Goldmark Brandeis are buried underneath the law school portico. His ashes are buried approximately fifty yards away from Auguste Rodin's The Thinker.[11]

Today

[edit]True to its history, the Louis D. Brandeis School of Law has retained a strong focus on practical legal education. The school offers students a chance to gain experience at its law clinic, on moot court teams, in skills competitions, and on three student-edited law journals. As part of the Samuel L. Greenebaum Public Service Program, the school also requires all students to complete 30 hours of law-related public service. The school has several pre-professional student-run organizations, including the Student Trial Lawyers Association, International Law Society, Student Health Law Association, Environmental Law Society, and The Brand (intellectual property).[citation needed]

In addition to pre-professional student organizations, there are also a number of student-run social and political organizations on campus. A partial list of these includes the Federalist Society, the American Constitution Society, Lambda Law Caucus, Black Students Association, Asian-Pacific Law Students Association, Jewish Law Students Association, Christian Legal Society, and Woman's Law Caucus.[citation needed]

The Law Library supports the curriculum and research needs of the school's faculty and students, and is open to the university community, practicing bar, and the general public.[13]

Deans of Louis D. Brandeis School of Law

[edit]- 1846–1873: Henry Pirtle

- 1881–1886: William Chenault

- 1886–1890: Rozel Weissinger

- 1890–1911: Willis Overton Harris

- 1911–1919, 1922–1925: Charles B. Seymour

- 1919–1921: Edward W. Hines

- 1925–1930: Leon P. Lewis

- 1930–1933: Neville Miller

- 1933–1934: Wendell Carnahan (interim)

- 1934–1936: Joseph A. McClain Jr.

- 1936–1946: Jack Neal Lott Jr.

- 1946–1957: Absalom C. Russell

- 1957–1958: William B. Peden

- 1958–1965: Marlin M. Volz

- 1965–1974, 1975–1976: James R. Merritt

- 1974–1975: Steven R. Smith (interim)

- 1976–1980: Harold Wren

- 1980–1981: Norvie L. Lay (interim)

- 1981–1990: Barbara B. Lewis

- 1990–2000: Donald L. Burnett Jr.

- 2000–2005: Laura Rothstein

- 2005–2006: David Ensign (interim)

- 2007–2012: Jim Chen[10]

- 2012–2017: Susan H. Duncan (interim)

- 2017–2018, 2021–2022: Lars Smith (interim)

- 2018–2021: Colin Crawford

- 2022–present: Melanie B. Jacobs

Employment

[edit]According to University of Louisville's 2018 ABA-required disclosures, 92% of the Class of 2018 was employed within ten months of graduation. This includes 76% who obtained full-time, long-term, JD-required employment ten months after graduation, excluding solo practitioners.[9] University of Louisville's Law School Transparency under-employment score is 6.7%, indicating the percentage of the Class of 2018 unemployed, pursuing an additional degree, or working in a non-professional, short-term, or part-time job nine months after graduation.[14]

Costs

[edit]The tuition at University of Louisville for the 2021–2022 academic year is $23,798 for residents and $28,798 out-of-state students.[15]

Notable alumni

[edit]- Jon Ackerson (1943– ), former member of both houses of the Kentucky Legislature, former member of the Louisville Metro Council, and Louisville lawyer[16]

- David Armstrong (1941–2017), mayor of Louisville, Kentucky

- Nick Baker (1937–), former Kentucky state senator from the 38th district, passed 1974 "girl's basketball" bill[17]

- Jeremy Beck (1960–), composer[18]

- Charles Booker,[19] former member of the Kentucky House of Representatives and candidate for U.S. Senate in 2020 and 2022

- William Campbell Preston Breckinridge (1837–1901) (class of 1857), former United States House of Representatives member from the Seventh District of Kentucky[20]

- William Marshall Bullitt (1873–1957) (class of 1895), served as Solicitor General of the United States 1912–1913[21]

- Daniel Cameron (politician), first African-American Attorney General for the Commonwealth of Kentucky.[22]

- John Breckinridge Castleman (1841–1918) (class of 1868), Confederate brigadier general

- Luke Clippinger (1972–), member of the Maryland House of Delegates

- Marlow Cook (1926–2016) (class of 1950), former United States Senator[23]

- Chris Dodd (1944–) (class of 1972), United States Senator from Connecticut, 1981–2011[24]

- Charles R. Farnsley (1907–1990) (class of 1930), former United States House of Representatives member from the Third District of Kentucky[25]

- Howard Fineman (1948–) (class of 1979), former Newsweek Magazine editor and chief Washington correspondent; Huffington Post editor[26]

- Fuller Harding (1915–2010), former member of the Kentucky House of Representatives (1942) and Taylor County county attorney for twenty-four years[27]

- Bob Heleringer (1951–) (class of 1976), former member of the Kentucky House of Representatives and Louisville lawyer[28]

- Todd Hollenbach (1960–), judge and Kentucky State Treasurer

- Michael C. Kerr (1827–1876) (class of 1851), former United States House of Representatives member from Indiana and 28th Speaker of the United States House of Representatives.[29]

- Joseph Koenig (1858–1929) (class of 1884), co-founder of Metal Ware Corporation

- Gerald Neal (1945–) (class of 1972), member of the Kentucky Senate 1989–present, first black person elected as party leadership in the Kentucky House or Senate [30][31]

- Louie B. Nunn (1924–2004) (class of 1950), 52nd governor of Kentucky[32]

- Emmet O'Neal (1887–1967) (class of 1910), former United States House of Representatives member from the Third District of Kentucky[33]

- Sannie Overly (1966–) (class of 1993), former member of the Kentucky House of Representatives[34]

- Diane Sawyer (1945–present), anchor of ABC News's nightly flagship program ABC World News, a co-anchor of ABC News's morning news program Good Morning America and Primetime newsmagazine.

- Greg Stumbo (1951–), former Kentucky Attorney General and former Speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives[35]

- David A. Tapp (1962–) (class of 1993), Judge on United States Court of Federal Claims, former judge of Kentucky Circuit Court[36]

- Oscar Turner (1867–1902), member of the United States House of Representatives

- Lawrence Wetherby (1908–1994), 48th Governor of Kentucky.

Publications

[edit]- University of Louisville Law Review

- Journal of Law and Education

- Journal of Animal and Environmental Law

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Best Law School Rankings – Law Program Rankings – US News". Archived from the original on February 8, 2017. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ^ "Louisville School Of Law Provides Briefing Service". Middlesboro Daily News. October 20, 1934. p. 3.

- ^ "Lambert to speak at local Rotary meeting". Corbin Times Tribune. August 29, 2001. p. 5.

...from the University of Louisville School of Law in 1974.

- ^ "University of Louisville, Louis D Brandeis School of Law". Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ^ University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law Guidebook (2009)

- ^ Klebanow, Diana, and Jonas, Franklin L. People's Lawyers: Crusaders for Justice in American History, M.E. Sharpe (2003)

- ^ Business First: "Law student's public service is bedrock aspect." Friday, March 10, 2006

- ^ "Home — Louis D. Brandeis School of Law". louisville.edu. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ a b "Louisville ABA §509 Employment Data". University of Louisville. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved March 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Cox, Dwayne D., and William J. Morrison, The University of Louisville (2000)

- ^ a b Louis Brandeis

- ^ "Home Page – Louis D. Brandeis School of Law". Archived from the original on June 3, 2010. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ^ "About the Law Library – Louis D. Brandeis School of Law Library". louisville.edu. Archived from the original on September 2, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ "University of Louisville Report, Overview | LST Reports". LST Reports by Law School Transparency. Archived from the original on May 31, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ "Tuition & Financial Aid — Louis D. Brandeis School of Law". Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ "Jon W. Ackerson". intelius.com. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ "The 'Basketball Bill' - 'The Right Thing to Do'" (PDF). legislature.ky.gov. Kentucky Historical Society. 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 6, 2022. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ "Composer and Lawyer Jeremy Beck | Department of Music | University of Pittsburgh". music.pitt.edu. Archived from the original on November 13, 2022. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Barton, Ryland (January 8, 2020). "State Rep. Charles Booker Files For McConnell's Senate Seat". WFPL News. Archived from the original on August 4, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ "William Campbell Preston Breckinridge". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "SOLICITOR GENERAL: WILLIAM MARSHALL BULLITT". The United States Department of Justice. Department of Justice. October 23, 2014. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- ^ "Attorney General Daniel Cameron – Kentucky Attorney General". ag.ky.gov. Archived from the original on November 13, 2022. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ "Marlow Cook". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Chris Dodd". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Archived from the original on November 12, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Charles R. Farnsley". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Howard Fineman, Business Speaker, Keppler Speakers Bureau". www.kepplerspeakers.com. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ "Fuller Harding". Columbia Magazine .com. Archived from the original on February 23, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Biography of Robert L. "Bob" Heleringer". equineregulatorylaw.com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Speaker of the House Michael Kerr of Indiana | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ "Gerald Neal". Kentucky Legislative Research Commission. Archived from the original on November 27, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ^ "State Senator Gerald Neal Now Part Of Ky. History". December 3, 2014. Archived from the original on February 3, 2015. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ "Louie B. Nunn". National Governors Association. Archived from the original on October 1, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Emmet O'Neal". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Overly sworn in as representative". The Bath County News-Outlook. January 16, 2008. p. 3. Archived from the original on May 14, 2024. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- ^ "Greg Stumbo". Project Vote Smart. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Biographical Directory of Federal Judges". Federal Judicial Center. Archived from the original on November 7, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2020.