List of World Heritage Sites in Romania

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Sites are places of importance to cultural or natural heritage as described in the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, established in 1972.[1] Cultural heritage consists of monuments (such as architectural works, monumental sculptures, or inscriptions), groups of buildings, and sites (including archaeological sites). Natural features (consisting of physical and biological formations), geological and physiographical formations (including habitats of threatened species of animals and plants), and natural sites which are important from the point of view of science, conservation or natural beauty, are defined as natural heritage.[2] Romania accepted the convention on 16 May 1990, making its historical sites eligible for inclusion on the list.[3]

As of 2024[update], there are 11 World Heritage Sites in Romania,[3] nine of which are cultural sites and two of which are natural. The first site in Romania, the Danube Delta, was added to the list at the 15th Session of the World Heritage Committee, held in Carthage in 1990. Further sites were added in 1993 and 1999 and some of the sites were subsequently expanded. Roșia Montană Mining Cultural Landscape was listed in 2021 and was immediately placed in the list of World Heritage in Danger due to plans to resume mining. The site Ancient and Primeval Beech Forests of the Carpathians and Other Regions of Europe is shared among 18 European countries. In addition, there are 17 sites on Romania's tentative list.[3]

World Heritage Sites

[edit]UNESCO lists sites under ten criteria; each entry must meet at least one of the criteria. Criteria i through vi are cultural, and vii through x are natural.[4]

| Site | Image | Location | Year listed | UNESCO data | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Danube Delta |

|

Tulcea County | 1991 | 588; vii, x (natural) | The Danube Delta, where the Danube river enters the Black Sea, is the largest European wetland. It is home to over 300 bird and 45 freshwater fish species, including the endangered sturgeons. Mammal species include European mink, European wildcat, Eurasian otter, and the threatened monk seal.[5][6] |

| Villages with Fortified Churches in Transylvania |

|

Sibiu, Alba, Harghita, Brașov, and Mureș County | 1993 | 596bis; iv (cultural) | This site comprises seven villages with fortified churches that were built between the 13th and the 16th centuries by Transylvanian Saxons. The settlement pattern and the organization of the villages has been preserved since the Middle Ages. Six villages (Câlnic, Dârjiu, Prejmer, Saschiz, Valea Viilor, and Viscri) were listed in the original nomination in 1993 while the village of Biertan (the fortified church is pictured) was added in 1999.[7] |

| Monastery of Horezu |

|

Vâlcea County | 1993 | 597; ii (cultural) | The monastery in the town of Horezu was founded in 1690 by Constantin Brâncoveanu, Prince of Wallachia, who was the namesake of the Brâncovenesc style of architecture. It is considered by UNESCO as a masterpiece of this style. It is known for its rich ornamental details and votive paintings. In the 18th century, an influential school of mural and icon painting was established in the monastery.[8] |

| Churches of Moldavia |

|

Suceava County | 1993 | 598bis; i, iv (cultural) | This site comprises eight churches built in the 15th and 16th centuries. In line with the regional period style, the facades of the churches are entirely covered by frescos inspired by Byzantine art. The paintings depict Biblical themes and are well preserved. The churches include the Beheading of Saint John the Baptist Church, the Assumption of the Virgin and of Saint George's Church of the Humor Monastery, the Church of the Annunciation of Moldovița Monastery, the Sacred Cross Church, the Saint Nicolas' Church of Probota Monastery, the Saint John the New Monastery, the Saint George's Church of the former Voroneț Monastery, and the Church of the Resurrection of Sucevița Monastery (pictured). The latter church was added to the list in 2010.[9][10] |

| Historic Centre of Sighișoara |

|

Mureș County | 1999 | 902; iii, v (cultural) | The historic centre of the city of Sighișoara dates from the 12th century. It is a well-preserved example of a small fortified medieval town shaped by the interactions of cultures from Central Europe and the Byzantine-Orthodox Southeastern Europe. It was founded by the Transylvanian Saxons, a community of German merchants and craftsmen. They have lived in the region for over 850 years, however, due to immigration in modern times, their culture will be preserved only through architectural monuments.[11] |

| Wooden Churches of Maramureş |

|

Maramureș County | 1999 | 904; iv (cultural) | This site comprises eight churches from the 17th and 18th century in Maramureș County. The churches are made of wood and they combine influences of Orthodox and Gothic architecture styles. Some of the common characteristics of the churches include tall, slim clock towers and roofs covered by shingles. The list includes the Church of the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple in Bârsana, the Church of Saint Nicholas (pictured) in Budești, the Saint Parascheva Church in Desești, the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin in Ieud Deal, the Church of the Holy Archangels in Plopiș, the Saint Parascheva Church in Poienile Izei, the Church of the Holy Archangels in Rogoz, and the Church of the Holy Archangels in Șurdești.[12][13] |

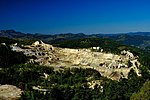

| Dacian Fortresses of the Orăștie Mountains |

|

Hunedoara County and Alba County | 1999 | 906; ii, iii, iv (cultural) | The six fortresses that comprise this site, Sarmizegetusa, Costeşti-Cetăţuie, Costeşti-Blidaru, Luncani-Piatra Roşie, Bănița, and Căpâlna, were built in the 1st century BCE and 1st century CE and served as protection against Roman conquest during the Roman-Dacian wars. They are representative examples of two characteristic types of forts of Late Iron Age Europe, the hilltop fort and its successor which evolved from it, the oppidum.[14] |

| Ancient and Primeval Beech Forests of the Carpathians and Other Regions of Europe* |

|

several sites | 2017 | 1133quater; ix (natural) | This site comprises undisturbed examples of temperate forests that demonstrate the postglacial expansion process of European beech from a few isolated refuge areas in the Alps, Carpathians, Dinarides, Mediterranean, and Pyrenees. The site was originally listed in 2007 as the Primeval Beech Forests of the Carpathians, shared by Slovakia and Ukraine, extended in 2011 to include the Ancient Beech Forests of Germany, extended in 2017 to list 12 areas in Romania and in some other countries, and further expanded in 2021 to include forests in a total of 18 countries.[15] |

| Roșia Montană Mining Cultural Landscape† |

|

Alba County | 2021 | 1552rev; ii, iii, iv (cultural) | Roșia Montană is located in the western part of the Romanian Carpathians. The area is rich in deposits of precious metals and has been a centre of gold mining starting in Bronze Age and continuing in the 21st century. Before the discovery of America, the area was the main European source of gold. Important remains date from Roman times, when the mining town of Alburnus Maior was founded. In the medieval period, mining was mostly carried out by families of peasant-miners, this pre-industrial practice continued until the nationalisation in 1948.[16] Upon the inscription, the site was immediately listed as endangered due to threats posed by plans to resume mining.[17] |

| Sculptural Ensemble of Constantin Brâncuși at Târgu Jiu |

|

Gorj County | 2024 | i, ii (cultural) | The group of monuments at Târgu Jiu was designed by the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși in 1937 to commemorate the soldiers who died in World War I. There are three sculptures in the assembly, The Table of Silence (Masa tăcerii), The Gate of the Kiss (Poarta sărutului), and the Endless Column (Coloana fără sfârșit), which is depicted in the picture. In the groups of monuments, the old Orthodox church of Targu-Jiu and the houses from the Calea Eroilor are included into UNESCO.[18][19] |

| Frontiers of the Roman Empire — Dacia |

|

several sites | 2024 | 1718; ii, iii, iv (cultural) | This site comprises the Dacian section of Roman Limes. Stretching over more than 1,000 km (620 mi), this was the longest land Roman border sector of Europe. Around 100 forts, 50 small fortifications, and more than 150 towers in Romania have been identified. Ruins of Micia are pictured.[20][21] |

Tentative list

[edit]In addition to sites inscribed on the World Heritage list, member states can maintain a list of tentative sites that they may consider for nomination. Nominations for the World Heritage list are only accepted if the site was previously listed on the tentative list.[22] As of 2024[update], Romania recorded 17 sites on its tentative list.[3][23]

| Site | Image | Location | Year listed | UNESCO criteria | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neamț Monastery |

|

Neamț County | 1991 | i, ii, iv (cultural) | The monastery was founded in the 14th century. The church was built in the late 15th century, during the reign of king Stephen III of Moldavia, and is the most representative example of the Moldavian style of religious architecture. The monastery has been one of the most important regional centres of culture, it had a printing press and a school.[24] |

| Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Churches in Curtea de Argeș |

|

Argeș County | 1991 | i, ii, iv (cultural) | Curtea de Argeș was the old capital of Wallachia. The princely court, dating from the 13th to 16th centuries, is now in ruins. The Church of St. Nicholas dates to the 14th century while the Curtea de Argeș Cathedral (pictured), a part of a former monastery, is from the 16th century.[25] |

| Rupestral Ensemble from Basarabi |

|

Constanța County | 1991 | (cultural) | The rock complex, located near the town of Murfatlar (formerly known as Basarabi) in an old chalk quarry, was converted into a monastic complex from the 10th to the 12th centuries. Several inscriptions are carved to the walls in different scripts, including Greek, Glagolitic, Cyrillic script, and Turkic runes. There are also several carvings depicting Biblical topics.[26] |

| Cule from Oltenia |

|

several sites | 1991 | iv, v (cultural) | Cule (singular: culă; from Turkish kule "tower, turret") are semi-fortified buildings found in the Oltenia (also known as Lesser Wallachia) region. They were built to watch important routes and were used by greater and lesser nobility. The Culă Greceanu is pictured.[27] |

| Densuș Church |

|

Hunedoara County | 1991 | i, iv (cultural) | The church was built at the latest in the 14th century on the site of a Roman temple, the materials of which were used in the construction. The interior paintings date from the 15th century.[28] |

| Historic Town of Alba Iulia |

|

Alba County | 1991 | iv, v, vi (cultural) | Alba Iulia lies on the site of a 2nd-century CE Roman camp Apulon. The medieval town was surrounded by bastions in the 18th century. Important buildings include the Catholic St. Michael's Cathedral from the 13th century, the Orthodox Coronation Cathedral from 1992, the Prince's Palace and the Batthyaneum Library. The Alba Carolina Citadel, a start fort, is pictured.[29] |

| Retezat Massif |

|

Hunedoara County | 1991 | (natural) | No description is provided in the nomination documentation.[30] |

| Pietrosul Rodnei mountain peak |

|

Bistrița-Năsăud County | 1991 | (natural) | No description is provided in the nomination documentation.[31] |

| Sânpetru Formation |

|

Hunedoara County | 1991 | (natural) | No description is provided in the nomination documentation.[32] The Sânpetru Formation is a geological deposit from the Late Cretaceous period (Maastrichtian stage), rich in dinosaur and other fossils. Artist's impression of the pterosaur Eurazhdarcho, discovered at the site, is pictured.[33] |

| Slătioara secular forest | Suceava County | 1991 | (natural) | This is a nomination of the Slătioara secular forest that has since been listed as a part of Ancient and Primeval Beech Forests of the Carpathians and Other Regions of Europe.[34][15] | |

| The Historic Centre of Sibiu and its Ensemble of Squares |

|

Sibiu County | 2004 | ii, iii, iv, v (cultural) | The first records of Sibiu, founded by Transylvanian Saxons, are from the year 1191. Since 1366, the town has been known as Hermannstadt and was the capital of the Saxon settlement in Transylvania. The Saxon University was founded in the town in the 15th century and in 1543, Sibiu was the centre of the Reformation in the region. Among the prominent architectural features of the town are the three interconnected squares of the Upper Town (Huet, Kleiner Ring, Grosser Ring), as well as a series of buildings in the Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque styles.[35] |

| The old villages of Hollókő and Rimetea and their surroundings* |

|

Alba County | 2012 | v (cultural) | This is a proposed extension to the Hollókő village, which has been listed as a World Heritage site in Hungary since 1987. Rimetea developed in the 17th and 18th centuries and has been deliberately preserved as a living example of rural life before the agricultural revolution of the 20th century. The village has a strong Hungarian community.[36] |

| Frontiers of the Roman Empire — The Danube Limes (Romania)* |

|

several sites | 2020 | ii, iii, iv (cultural) | This is a transnational nomination covering sites with Roman fortifications along the Danube river. The reconstructed gate at Porolissum is pictured.[37] |

| Former Communist Prisons in Romania |

|

several sites | 2024 | vi (cultural) | This nomination comprises five former Communist prisons: Jilava (pictured), Râmnicu Sărat, Pitești, Făgăraș, and Sighetu Marmaţiei penitentiaries.[38] |

| Movile Cave | Constanța County | 2024 | viii, ix, x

(natural) |

The cave is nominated as its aquifer forms a unique, isolated ecosystem shaped by the high concentration of sulfur compounds but little oxygen, with most organisms relying on chemosynthesis to survive.[39] | |

| Princely religious foundations in Wallachia and Moldavia |

|

Argeș County and Iași County | 2024 | i, ii

(cultural) |

The nomination combines two churches: the Cathedral Church of The Assumption of Virgin Mary at Curtea de Argeş (a tentative site since 1991) and the Church of the Three Holy Hierarchs at Iaşi (a former tentative site, pictured).[40] |

| Royal Residences of Sinaia |

|

Prahova County | 2024 | ii, iv, vi

(cultural) |

The nomination comprises parts of Sinaia built during the reign of Carol I, most notably the Peleș Castle (pictured), the Pelișor Castle, and the Foișor Castle.[41] |

References

[edit]- ^ "The World Heritage Convention". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 23 May 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ^ "Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Romania". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "UNESCO World Heritage Centre – The Criteria for Selection". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 12 June 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "Danube Delta". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 27 January 2008. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "Villages with Fortified Churches in Transylvania". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "Monastery of Horezu". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "World Heritage Committee also approves three extensions to World Heritage properties in Austria, Romania and Spain". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 5 August 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ^ "Churches of Moldavia". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "Historic Centre of Sighișoara". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "Wooden Churches of Maramureş". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Baboș, Alexandru (2004). Tracing a Sacred Building Tradition. Wooden Churches, Carpenters and Founders in Maramureș until the Turn of the 18th Century (Thesis). Lund University. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "Dacian Fortresses of the Orastie Mountains". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Ancient and Primeval Beech Forests of the Carpathians and Other Regions of Europe". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Roșia Montană Mining Landscape". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Cultural sites in Africa, Arab Region, Asia, Europe, and Latin America inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage List". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 28 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "L'ensemble monumental de Tirgu Jiu" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ ""Calea Eroilor" de Brâncuşi şi "Frontierele Imperiului Roman - Dacia" au fost incluse în Lista Patrimoniului Mondial UNESCO". 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Frontiers of the Roman Empire — Dacia (Romania)". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Frontiers of the Roman Empire - Dacia". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Tentative Lists". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ "UNESCO World Heritage Centre – Tentative Lists". Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ "Le Monastère de Neamt" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Eglises byzantines et post-byzantines de Curtea de Arges" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "L'ensemble rupestre de Basarabi" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Les " coules " de Petite Valachie" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "L'église de Densus" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Le noyau historique de la ville d'Alba Julia" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Massif du Retezat" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Pietrosul Rodnei (sommet de montagne)" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Sinpetru (site paléontologique)" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Vremir, M. T. S.; Kellner, A. W. A.; Naish, D.; Dyke, G. J. (2013). Viriot, Laurent (ed.). "A New Azhdarchid Pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous of the Transylvanian Basin, Romania: Implications for Azhdarchid Diversity and Distribution". PLOS ONE. 8 (1): e54268. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...854268V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054268. PMC 3559652. PMID 23382886.

- ^ "Codrul secular Slatiora (forêt séculaire)" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "The Historic Centre of Sibiu and its Ensemble of Squares". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "The old villages of Hollókő and Rimetea and their surroundings". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Frontiers of the Roman Empire — The Danube Limes (Romania)". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ "Former Communist Prisons in Romania". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 15 April 2024.

- ^ "Movile Cave". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 15 April 2024.

- ^ "Princely religious foundations in Wallachia and Moldavia". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 15 April 2024.

- ^ "Royal Residences of Sinaia". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 15 April 2024.