Tyndall Glacier (Alaska)

| Tyndall Glacier | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Valley glacier/Tidewater glacier |

| Location | Alaska |

| Coordinates | 60°11′46.17″N 141°8′35.69″W / 60.1961583°N 141.1432472°W |

| Length | 19 kilometers |

| Terminus | Taan Fjord |

| Status | Receding |

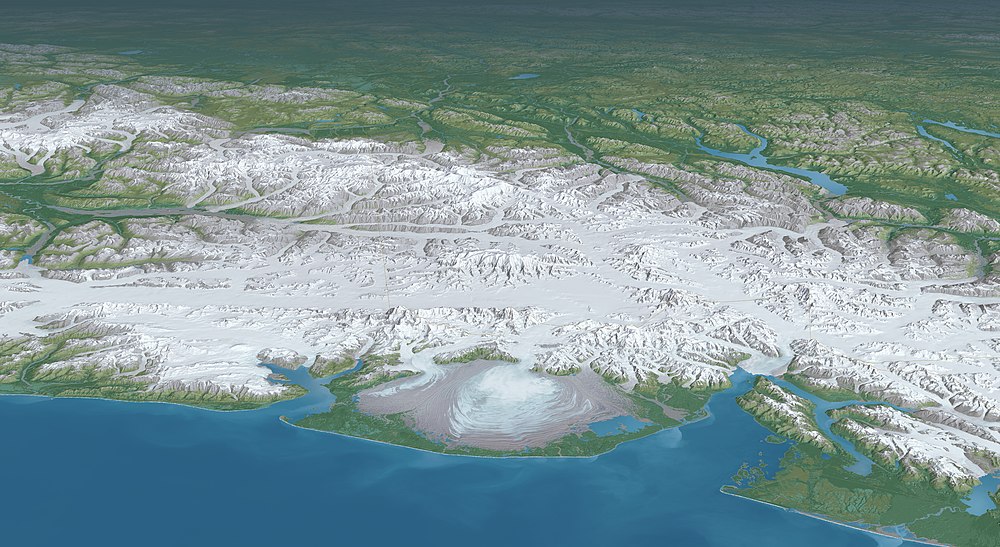

Tyndall Glacier is a valley/tidewater glacier in the U.S. state of Alaska. The glacier lies immediately west of 141° West longitude, within the boundaries of the Wrangell–Saint Elias Wilderness, itself part of Wrangell–St. Elias National Park & Preserve, in the borough of Yakutat, Alaska.

Named for John Tyndall (a 19th-century Irish physicist, natural philosopher, and glaciologist), Tyndall Glacier originates in the basin formed by the southwestern face of Mount Saint Elias (the second-tallest mountain in the United States and the fourth-tallest in North America), as well as Mount Huxley, The Hump, and Haydon Peak in the Saint Elias Mountains. From there it extends 19 kilometers, trending southwest and terminating in Taan Fjord, an arm of Icy Bay.[1][2] Together with the Yahtse and Guyot glaciers, it once occupied the entirety of Icy Bay; as the glaciers have retreated the bay has opened up.

Tyndall Glacier is sometimes used as a landing area for bush planes by parties seeking to climb Mount Saint Elias, as it was during the first winter ascent of the peak.[3]

History

[edit]Tyndall Glacier first started to advance out of Taan Fjord around AD 1400, and reached its Little Ice Age maximum length at the mouth of Icy Bay at some point prior to 1794, when George Vancouver mapped the ice extending out from Icy Bay.[4] Tyndall Glacier then began to retreat in 1905. Between 1938 and 1961, Tyndall Glacier's terminus—where the glacier ends and calves into the fjord—retreated approximately 3 kilometres (1.9 mi), until it separated from Guyot Glacier in Icy Bay around 1961.[4]

After that, the Tyndall Glacier then retreated approximately another 10.5 mi (16.9 km) between 1961 and 1991.[5][6] According to a 2006 study, in the previous 40 years the glacier lost approximately half of its 1961 volume (equivalent to 3.19 × 1010 m3) and the glacier's thickness decreased by over 300 meters at its terminus.[4] Since 1991, the glacier's retreat has stabilized, with a terminus at a "shallow bedrock constriction at the head of the fjord," called Hoof Hill.[7][4]

Mountaineer and explorer Bradford Washburn noted in 1992 that the glacier's retreat has meant that the summit of Mount Saint Elias is only twelve miles from tidewater, exacerbating the peak's immense vertical relief.[8]

2015 landslide and megatsunami

[edit]Tyndall Glacier and Icy Bay are notable for being the site of an enormous landslide and subsequent megatsunami in 2015.[9]

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]- Malaspina Glacier (a nearby piedmont glacier and the largest such in the world)

- List of glaciers

References

[edit]- ^ "Geographic Names Information System". edits.nationalmap.gov. Archived from the original on January 6, 2023. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ Williams, Haley B.; Koppes, Michele N. (2019). "A comparison of glacial and paraglacial denudation responses to rapid glacial retreat". Annals of Glaciology. 60 (80): 151–164. doi:10.1017/aog.2020.1. ISSN 0260-3055.

- ^ "Mount Saint Elias, First Winter Ascent". Climbs And Expeditions. American Alpine Journal. American Alpine Club. 1997. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Koppes, Michèle; Hallet, Bernard (2006). "Erosion rates during rapid deglaciation in Icy Bay, Alaska". Journal of Geophysical Research. 111 (F2): F02023. doi:10.1029/2005JF000349. ISSN 0148-0227. Archived from the original on November 1, 2023. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ Mooney, Chris (September 6, 2018). "One of the biggest tsunamis ever recorded was set off three years ago by a melting glacier". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on August 1, 2023. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ Pappas, Stephanie (September 8, 2018). "Warnings Abounded Before Massive Alaska Landslide and Tsunami". Live Science. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ Higman, Bretwood; Shugar, Dan H.; Stark, Colin P.; Ekström, Göran; Koppes, Michele N.; Lynett, Patrick; Dufresne, Anja; Haeussler, Peter J.; Geertsema, Marten; Gulick, Sean; Mattox, Andrew (September 6, 2018). "The 2015 landslide and tsunami in Taan Fiord, Alaska". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 12993. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30475-w. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6127189. PMID 30190595.

- ^ "AAC Publications - North America, United States, Alaska, Mount St. Elias as a Coastal Peak". publications.americanalpineclub.org. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ Rozell, Ned (April 7, 2016). "The giant wave of Icy Bay". alaska.edu. Archived from the original on July 11, 2023. Retrieved June 16, 2020.