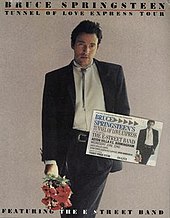

Tunnel of Love Express Tour

| Tour by Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band | |

The tour was performed to promote the album Tunnel of Love. | |

| Associated album | Tunnel of Love |

|---|---|

| Start date | February 25, 1988 |

| End date | August 4, 1988 |

| Legs | 2 |

| No. of shows | 67 |

| Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band concert chronology | |

The Tunnel of Love Express Tour was a concert tour by Bruce Springsteen and featuring the E Street Band with the Horns of Love that began at the end of February 1988, four and a half months after the release of Springsteen's October 1987 album, Tunnel of Love. Considerably shorter in duration than most Springsteen tours before or since, it played limited engagements in most cities which fueled the high demand. The tour finally grossed US$50 million not counting merchandise. Shows were held in arenas in the U.S. and stadiums in Europe. A historic performance in East Berlin took place on July 19, 1988.

The Tunnel of Love Express was designed to disorient Springsteen's audiences. A theatrical entrance began the show, a full horn section appeared, band members were rearranged from their customary positions, and on-stage spontaneity was kept to a minimum. Set lists were unusually static, and many of Springsteen's most popular concert numbers were omitted altogether. Instead, the shows featured Springsteen B-sides and outtakes as well as renditions of obscure genre songs by others. Critical reaction to the concerts was generally favorable, with some mixed reviews, while audiences were sometimes baffled.

The show featured backup singer Patti Scialfa brought to center stage as the object of sexually themed presentations deemed unusual for Springsteen. That, combined with the dour nature of many Tunnel of Love songs, led to speculation that Springsteen's marriage to Julianne Phillips was troubled. Further visual evidence of Springsteen and Scialfa becoming a couple emerged as the tour progressed, his separation from Phillips was officially confirmed, and for the first time Springsteen became the subject of a tabloid fervor. Springsteen and Scialfa eventually married, and the Tunnel of Love Express shows were the last full-length ones Springsteen would play with the E Street Band for eleven years.

Itinerary

[edit]The tour came four and a half months after the release of Springsteen's 1987 album, Tunnel of Love, which had sold well – although nowhere near the blockbuster levels of its predecessor, Born in the U.S.A., which the album was partly a counter-reaction to – and already generated a hit single in "Brilliant Disguise".[1][2][3][4] In part, the unusual lag reflected the ambivalence of the album; Springsteen had first recorded it solely by himself, and then some E Street Band parts had been dubbed in.[2] Indeed, Springsteen and the band had started to drift apart over the previous two or three years, seldom speaking amongst themselves.[5] Springsteen had considered going out on tour solo, and his management had provisionally booked 3,000-seat halls around the country.;[3] however, he eventually decided against that approach, feeling the tone of the resulting show would be too dark.[3]

The tour was officially announced on January 6, 1988.[6] One of the few Springsteen tours to be formally named, the "Express" part came from its shorter duration – roughly half his typical length – and the shorter stays in any given location, generally just one or two nights.

The United States leg of the tour took place in arenas,[7] starting on February 25 at the Worcester Centrum and continuing for 43 shows. There were five-night stands in two major markets, at the Los Angeles Sports Arena and at New York City's Madison Square Garden; the shows at the latter closed the American leg on May 23. The European leg commenced on June 11 at the Stadio Comunale in Turin, Italy, and continued for 23 shows in stadiums, concluding the tour on August 4 at Barcelona, Spain's Camp Nou.[8]

The tour became the first one in which Springsteen did not play his home state of New Jersey; speculation that he would play a special series of dates there upon his return from the European leg proved unfounded.[9][10]

The show

[edit]Springsteen's concerts from his beginnings up through the massively popular Born in the U.S.A. Tour had been a linear progression of basically the same show, scaled to greater and greater heights. Apparently having achieved all he could along those lines, and feeling that the Born in the U.S.A. Tour had done too much of it, Springsteen sought to change directions.[3][4][11] As Springsteen later wrote in his 2016 memoir, "Tunnel was a solo album, so I wanted to distance the tour from being compared to our USA run."[12] The Tunnel of Love Express was, as rock author Jimmy Guterman later wrote, "a tour intended to disorient."[13]

Springsteen augmented the E Street Band with a five-piece horn section led by Richie "La Bamba" Rosenberg.[4] Generally known as The Miami Horns, they had recently been performing on the Jersey shore bar scene as La Bamba and the Hubcaps[4] and were billed on this tour as the Horns of Love.[14][15] This addition to the band would be both highly visible and audible. (Springsteen had wanted to carry a ten-piece band with a horn section going back to his pre-E Street, Bruce Springsteen Band days, but had not been able to afford it heretofore.[16])

The stage backdrop was a tapestry of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden.[17] The entrance of the band on the stage, heretofore a casual affair, was now elaborate and stylized. It was set up to mimic fairgoers entering a carnival ride,[11] with Springsteen assistant Terry Magovern playing a ticket-taker at the gate near an ominous and foreshadowing sign that said:[1]

This is a dark ride

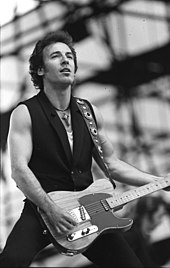

(One of the tour T-shirts being sold proclaimed "This is not a dark ride", but as both a newspaper reviewer wrote at the time, and a fan who later became an author wrote later, that was a lie.[18][19]) Roy Bittan was already on synthesizer as an extended intro to "Tunnel of Love" was played. Band members entered the stage two by two, taking tickets from Magovern, each (with the help of a professional costumer) more sharply dressed than for previous tours:[2] Max Weinberg and Danny Federici, Garry Tallent and Nils Lofgren, the horn section. Next came Patti Scialfa in a tight mini-skirt,[20] big hair and carrying a bunch of balloons: more foreshadowing. Once in their positions, band members started their parts in the song.[21] Penultimately, Clarence Clemons entered with a single rose between his teeth. Springsteen appeared last, dressed in trousers, a jacket and white shirt that departed from his past denim-and-bandanas look, matched the Annie Leibovitz-photographed look from the Tunnel album cover, and emphasized the greater formality of what was about to come.[11][22][12] Once present, the band's traditional positions on stage were flipped:[13] now Clemons was on the right, Bittan on the left, and so on; Weinberg moved from the center to the side, and backup singer Scialfa from the back riser to the front where Clemons had been.[4] Springsteen declared this to be evidence of his desire to shake things up when rehearsals began: "The first thing I did was make everyone stand in a different place."[4]

The music of the show itself was a departure, and the show overall more subdued than in the past,[11] with the return to arenas making the show more accessible.[23] Yet at the same time the stage presentation was more stylized and choreographed than on any tour before.[21] The country-influenced rock and serious ballads of the new album were not ideal stage material.[22] Audiences expected the moody "Tunnel of Love" to open, but the second slot — which in past years was filled by well-known rousers such as "Badlands", "Out in the Street" or "Prove It All Night" — now was "Be True", an obscure, lightweight B-side[22] to the underperforming 1981 "Fade Away" single. The show's theme was quickly established — an examination of relationships, often of the failed, sour variety, much as the album had been.[1] A long spoken introduction to "Spare Parts" over a quiet piano backing by Roy Bittan reiterated the song's hardscrabble setting.[4][24] Theatrics were up throughout A tortured rendition of the Biblical "Adam Raised a Cain", sitting on a park bench with Clemons in a long prologue to "All That Heaven Will Allow",[25] the horn section throughout swooping and swaying and doing every bit of stage shtick known to horn sections.

Plenty of songs (typically eight or nine) from Tunnel of Love appeared,[26] but the dominance of obscurities, of B-sides and outtakes, continued,[4][27] with immediate audience response sacrificed for what might be a slower but deeper understanding.[20] Springsteen said, "The idea on this tour is that you wouldn't know what song was gonna come next. ... [The show feels] real new, real modern to me. I figure some people will wrestle with it a little bit. But that's okay."[4] Some fans worried that Springsteen looked like he was not having as much fun on stage as in the past.[28] The first set saw "Roulette", a previously unreleased number from The River sessions about the Three Mile Island accident,[27] (which was paired with the previous tour's "Seeds" to lend an element of sociological anguish to the personal).[29] The second set saw Springsteen assuming the manner of a televangelist or professional wrestler[25] delivering "I Am a Coward", a remake of Gino Washington's little-known 1964 local Detroit hit "Gino Is a Coward",[30][12] and "Part Man, Part Monkey", a never-before-heard, Springsteen-written quasi-reggae ode to the Scopes monkey trial by way of Mickey & Sylvia's "Love is Strange".[30] Audiences were bewildered.[17][27]

Gone completely were several of Springsteen's most popular numbers and traditional concert warhorses: "Badlands", "The Promised Land", "Thunder Road", "Jungleland".[3][14] Springsteen had said as the tour began, "when I went to put this show together, I said, 'Well, what were the songs that were the kind of cornerstones of what I had done? Those are the ones I automatically put to the side.'"[3]

The first set did close with a blockbuster pairing of "War" and "Born in the U.S.A."; compared to the latter's opening of shows during the Born in the U.S.A. Tour, it now served to sum up a set's worth of personal struggles and counter any mistaken notions about the song's patriotic intent.[4][30] The first hour and a half of the show featured no selections from Springsteen albums prior to Born in the U.S.A. other than "Adam Raised a Cain".[22] The main set closer, a position long held by "Rosalita" until cut during the Born in the U.S.A. Tour, was now held by the fairly obscure, roadhouse-flavored and hotly played, Springsteen-written-but-Joan Jett-recorded "(Just Around the Corner to the) Light of Day" (it would hold this position for band-based Springsteen tours through the end of 2000).[21][23][24]

The encores began with Springsteen's signature song, "Born to Run", recast completely and slowly played solo by Springsteen on acoustic guitar and harmonica and with a melancholy feel,[23][24] albeit with the band standing behind him,[21] sometimes with an audience sing-along of "whoa-whoa's" at the end. Springsteen prefaced these performances with an introduction along the same lines every night:[31] "Before we came out on tour, I was sitting around home trying to decide what we were gonna be doing out here this time. What I felt I wanted to sing and say to you." After detailing how he came to write "Born to Run" a decade and a half earlier, he would say that its overt theme of escapism had concealed a deeper search for connection and for a place its protagonists could call home. That, now, to Springsteen meant a place deep within oneself.[14][31] He concluded by saying, "I wanna do this song tonight for all of you, wishing with all my heart that you have a safe trip to home."[4][32]

After this, Springsteen finally retreated into normalcy, with the last half-hour of the show an upbeat, redemptive sequence that The New York Times described as a "rip-roaring, cinderblock-shaking jubilee."[18][33] Presented were top hits such as "Hungry Heart" and "Glory Days" (both with heavy roles from the horn section)[17] and even, in the second encores, the resurrection of a couple of veteran numbers dropped midway through the Born in the U.S.A. Tour, "Rosalita" and the "Detroit Medley".[4][17] Springsteen reasoned that the latter's "Devil with a Blue Dress On" was actually the ultimate moment of the show, as the 'trick' of juxtaposing serious, emotional content with exciting entertainment was pulled off.[4] But those last two would also be gone by the latter stages of the American leg, and the second encore would be filled with more regional obscurities such as The Sonics' "Have Love, Will Travel" and unlikely attempts at Roy Orbison's "Crying". The encores also delved into Springsteen's longtime interest in soul music, showcasing Percy Sledge's 1967 arrangement of Elvis Presley's "Love Me Tender", Arthur Conley's "Sweet Soul Music", and a longtime staple, Eddie Floyd's "Raise Your Hand".[27]

Overall, shows ran a little under three hours in length, up to an hour shorter than what audiences had become accustomed to with Springsteen.[22] Set lists were unusually static during the tour,[20][21][22] a deliberate decision by Springsteen, who saw the show as "focused and specific".[4] Not having to play multiple shows in many venues also helped, although some of the faithful[34] were travelling to multiple cities to see the tour. During the early weeks, often only one song changed per night; a two-night stand at the Philadelphia Spectrum saw no changes at all, highly unusual especially in Springsteen's home territories.[22]

During later shows on the European leg, setlists began to change with occasional surprise additions.[9] "Badlands" began appearing, and "Thunder Road" a couple of times,[22] while televangelist-styled song introductions were dropped due to lack of cultural context.[25] The many Americans at a West German show at Frankfurt's Waldstadion waved flags as "Born in the U.S.A." was played, with U. S. Ambassador to Germany Richard Burt in attendance.[35]

The East Berlin show

[edit]

Most unusual of the European shows was one in East Berlin on July 19, 1988, some 16 months before the Berlin Wall came down. It was organized by the socialist youth movement Free German Youth in an attempt to relieve some tension among the younger populations of East Germany by bringing in one of the most popular of Western musicians.[36] Other Western rock and pop stars, such as Joe Cocker, were brought in as part of this effort, which began in 1987.[37] Springsteen in particular was extolled by state newspaper Neues Deutschland as a working-class American who "attacks social wrongs and injustices in his homeland."[38]

The show was held at the Radrennbahn Weißensee cycling track, far away from the Wall (previous concerts held on the Western side of the Wall by Pink Floyd and Michael Jackson had given East Berlin security forces trouble in keeping youths away from the Eastern side to listen).[36] Initial news reports estimated that there were some 160,000 fans in attendance.[38] This was practically one percent of the German Democratic Republic's entire population.[39] It was the largest audience of Springsteen's career to that point[40] and the largest ever to see a rock concert in the GDR.[38] Much of the concert was broadcast live on both state television and radio,[39] although the television broadcast quality was shaky.[36] While some Western artists would not accept the local Mark der DDR currency and thus would not play in the GDR,[36] Springsteen did, and was paid 1,000,000 Mark der DDR for the performance, with another 340,000 Mark der DDR being paid for the television rights.[37]

Springsteen modified the set list for the occasion, opening with "Badlands" for the first time on the Express[41] and making a tour debut for "Promised Land". Before playing Bob Dylan's "Chimes of Freedom", Springsteen stated in phonetically recited German, "I want to tell you, I'm not here for or against any certain government, but to play rock 'n' roll for you East Berliners ... in the hope that one day, all barriers will be torn down."[39] GDR officials took advantage of a tape delay to delete Springsteen's words on the broadcast.[39][42] The show became one of the most politically meaningful moments of Springsteen's career.[39]

Since the initial reports, some estimates of the crowd size have been increased, often to a figure of 250,000[37] or 300,000.[36][41] Internet posters have made claims as high as 500,000; German public broadcaster Deutsche Welle has written, "160,000 tickets were sold, but it's said that a crowd of 500,000 people celebrated ..."[43] In any case, the costs of putting on the event and other concerts with Western stars led to the Free German Youth running out of money and having to be subsidized by a special fund of the state.[37]

In 2013, Erik Kirschbaum, a Berlin-based journalist, published his book Rocking the Wall: The Berlin Concert That Changed the World, which argues that the Springsteen concert was a signal event in the process that led to the Peaceful Revolution, the fall of the Wall, and Die Wende.[36] Gerd Dietrich, a professor of history at Humboldt University, was quoted saying that "Springsteen's concert and speech certainly contributed in a large sense to the events leading up to the fall of the wall. It made people … more eager for more and more change … It showed people how locked up they really were."[36][41] Thomas Wilke, who has studied the impact of popular music in East Germany, said "It was a topic of discussion for quite some time afterwards. There was clearly a different feeling and a different sentiment in East Germany after that concert."[36]

Life imitating art imitating life

[edit]From the first release of Tunnel of Love, there had listeners who wondered if some of the gloomy portrayals of interpersonal relationships on the album indicated that Springsteen's 1985 marriage to actress and model Julianne Phillips was in trouble.[44] Others, however, cautioned against such interpretations, pointing out that Springsteen's 1982 album Nebraska had been full of intense tales of spree killers and other criminals, of which Springsteen clearly had no personal experience.[44][45] Los Angeles Times music writer Robert Hilburn, interviewing Springsteen at the Worcester start of the tour, wrote that "Springsteen seemed extremely comfortable sitting on a sofa with his wife in the dressing room area – a picture that seemed to contradict the speculation that Tunnel of Love's songs of troubled romance reflected signs of trouble in his own marriage."[3]

In addition to everything else, what was different about the Tunnel of Love Express was Springsteen's first go at explicit carnality,[27] from the opening "Tunnel of Love", where he and Scialfa sang cheek to cheek with lips nearly touching at the same microphone, to other numbers such as "Part Man, Part Monkey".[30] A centerpiece of the second set was an eight-minute reworking of one of The River's casual rockers, "You Can Look (But You Better Not Touch)". Now it was recast into rockabilly mode, with a half-spoken, half-sung introduction detailing a youth's frustrations up to the iconic car parked with a girlfriend on a lovers' lane. Out come the horn section, sans horns, to do synchronized dancing[30] and sing call-and-response. Out come Scialfa and two women from backstage, three temptresses for the six assembled men. Around they circle each other, as Springsteen sings "You Can Look", resting the microphone below his belt in between lines. Finally the song winds down, as Springsteen and Scialfa stare at each other. Springsteen goes back to the drum kit, where a tray full of water and a sponge are. In tours past, this was a classic moment of Springsteen the relentless showman; he would sponge off his head, gulp down water and spray it over the stage, revitalizing himself to keep on playing for a few more hours. Now, however, he took the sponge, pulled his pants out by his belt buckle, and squeezed the water down into his crotch. Perhaps tame by the standards of Prince or Madonna at the time, but for Springsteen and his audience, a line had been crossed.

Newsday wrote, "Dripping wet during 'Part Man, Part Monkey' – which is as sexual a message as Springsteen has ever transmitted live – Springsteen was, literally, steaming."[27] Amplified deep breathing.[27]

This was all a big change for Scialfa, who had stayed in the background during the 1984–1985 Born in the U.S.A. Tour, her first. Early on the tour, she said in an interview about her new role: "Bruce coaxed me and urged me to reach. He was very patient, very willing to teach. He had a lot of confidence in me. ... I feel real complete working with him on stage. It's like for a moment nothing bad can happen to you. It's a wonderful give-and-take. You go through every emotion every night."[46] The tour soon proved sufficiently strenuous for her that she began gulping down milkshakes in an effort to restore lost weight to her 5-foot-8, 117-pound frame.[47]

But there was more to the Tunnel of Love Express than just what Springsteen had planned.[32] On stage, Scialfa had now become Springsteen's principal vocal partner (a role held in the past by the departed Steve Van Zandt) as well as principal foil (supplanting Clarence Clemons),[48] and in this number and others, the way Springsteen and Scialfa approached each other, and how they held their bodies as they sang together, made their byplay the center of the show right from the "Tunnel of Love" opener.[30][46][49][50] Springsteen biographer Dave Marsh later wrote of the sparks flying from the interaction, "You could have written it off just to musical magic ... if you were dumb as a doorstop", and said that even those that oblivious could not have missed the meaning of the body language during their performance on "One Step Up", in which a man lists metaphors for the failing love in his marriage, expresses his lack of desire to find it again, and starts casting a wandering eye about.[49]

Springsteen and Scialfa's involvement had thus been rumored since early on the tour.[40] Suspicion and confirmation came in stages. Phillips had traveled with the tour initially and even danced onstage during "You Can Look", but at times had looked lost and lonely backstage; she then left (apparently to try out for or shoot a film, variously reported as Sweet Lies with Treat Williams, Fletch Saves with Chevy Chase, or Skin Deep directed by Blake Edwards).[46][51][52][53] Springsteen and Phillips spent their May 13 wedding anniversary apart.[54] During the Madison Square Garden shows in mid-May, fans and the New York newspapers began noticing that Springsteen was not wearing his wedding ring on stage.[44][51][54]

A National Enquirer headline declared, "Bruce Springsteen's Marriage in Trouble", soon followed on June 9 by USA Today asking "Is Bruce on the Loose?".[44] Springsteen's management initially declined any comment.[44] The European leg of the tour started in Italy, with three shows in mid-June in Rome. Paparazzi caught Springsteen and Scialfa snuggling each other in their underwear (sometimes described as nightshirts) on a Rome balcony in one photograph and dressed but lounging together on a single deck chair with drinks in hand in another.[5][40][46][55] An Italian paper wrote, "There are no doubts ... Patti and Bruce really love each other."[46] A tabloid fever was underway.[49][56]

On June 17, Phillips' publicist officially confirmed that Springsteen and Phillips had split .[46][54] Attention did not diminish; by the time the tour hit France, photographers were capturing Springsteen and Scialfa walking arm in arm through Parisian streets or lolling in the grass in one of the city's parks.[57][58] When the show reached Wembley Stadium in London, the Fleet Street papers were preoccupied with judging whether the two really were an item: as USA Today reported, The Star and News of the World said yes, The Daily Mail was unsure, while the Sunday Mirror ran a photograph of Springsteen staring intently at his guitar and claimed it was the only love in his life.[59] The goings-on around Springsteen became fodder for jokes on late-night talk shows in the U.S.[60]

Later that month, Springsteen's management elaborated that the cause had been that they just grew apart, and explicitly denied tabloid reports that the needs of her career or disagreements about having children had played a role.[54] Phillips subsequently said the same thing in an interview in Us magazine.[53] On August 30, Phillips filed for divorce, which was made final in March 1989.[5] Scialfa later said of the period, "I just thought, I can't take this ... Bruce and I had gotten together, it was a very turbulent time."[56] Springsteen himself said, "My first wife's one of the best people I've ever met. She's lovely, intelligent – a great person. But we were pretty different, and I realized I didn't know how to be married."[61]

English fans interviewed had mixed reactions to the romantic developments,[59] while American fans interviewed, after expressing some sympathy and unease for those involved, generally felt that Springsteen's private life was his business.[45] Some belonged to a camp that had never seen Phillips as a good match for Springsteen from the start.[45][53][58][62] Others were surprised that Springsteen would end up in the middle of a messy and indiscreet love triangle.[58][60] Some married fans did not like Springsteen's seemingly cavalier behavior, even if they had not approved of Phillips, and some longtime fans did not like Scialfa's usurping of the Clemons stage role.[48] On the other hand, some female fans were happy to see their idol possibly available again.[60] There was no immediate drop in Springsteen album sales or radio airplay.[60]

The two primary organs of the Bruce faithful at the time, Backstreets Magazine and the "Springsteen party line" (a telephone-based precursor to Springsteen fan groups and mailing lists on the Internet), said nothing about the developments at all.[45] Music writer David Hinckley said that while Springsteen had never promoted himself as a hero or role model, he had nonetheless built a bond of faith with his fan base around the notion of doing the right thing. Hinckley wondered whether Springsteen could "win the faithful back".[28] Music writer Gary Graff said that because Springsteen espoused "hanging tough and solving problems" that made his marital failure "especially intriguing" to the public.[60] The affair continued to draw the attention of the celebrity and supermarket press, eventually including a long piece in Woman's World magazine that quoted Judith Kuriansky, a psychologist and television talk show host, to the effect that Springsteen was going through a midlife crisis.[58] Quasi-official Springsteen biographer Marsh would later write that the separation had occurred in early May at the end of the West Coast portion of the American leg,[49] while an Us magazine story based around a Phillips interview placed it sometime between the early stages of the tour and the couple's May 13 anniversary.[53] Regardless of exactly when the marriage ended and the new relationship began, the impression left upon the wider public was that Springsteen was a heartless man cheating on his wife an ocean away, Phillips was humiliated, and Scialfa was the "other woman".[49]

The search for a deeper personal connection that Springsteen had mentioned during his "Born to Run" introduction had left him, in an interview during the tour, comparing his fame and situation to that of Elvis Presley and Michael Jackson.[4] But his quest to undermine his Born in the U.S.A.-era fame with a more subdued album and smaller-scale tour had ended up in most unexpected fashion.[63]

Critical and commercial reception

[edit]Due to the limited number of dates in each city and the continuing popularity of Springsteen from the 1984–86 period, tickets were hard to come by.[64] Long waits for the chance to buy tickets were common.[64][65] This was in the era of the "ambush sale", when often no advance word would be given of when tickets were going on sale (or bracelets for the rights to get tickets were being distributed).[34][66] This was especially the case for this tour, as in some locations such as for Nassau Coliseum tickets went on sale much closer to the event date than usual.[67] Thus, for example, in the weeks preceding the New York area shows, several dozen fans would gather at major Ticketmaster outlets on Saturday mornings, listening on portable radios with the idea that something might be happening right then. Most often, nothing would happen, and a rock radio disc jockey would then confirm that no tickets were going on sale that day. Or fans would gather outside the box office at the Centrum in Worcester, hoping that ticket bracelets might suddenly be distributed that day, and be suddenly rewarded if they were.[34] The alternative of buying tickets over the telephone once they went on sale was often fruitless.[10]

The disparity between supply and demand meant high prices for scalpers, with $22.50 tickets to the Nassau Coliseum shows on Long Island going for anywhere from $100 to $400[64] and other shows expensive as well.[10][19] Undercover police worked venue parking lots to try to curb the practice.[64] Fans from all over Ohio and parts of Indiana attended the Richfield Coliseum shows in Cleveland, with some paying scalper prices.[23] Fans in Rockford, Illinois staged an (unsuccessful) petition drive to get Springsteen to add their city to the tour's routing.[68]

The three kickoff shows in Worcester sold out in two hours[66] (the site having been chosen for the tour opening, the venue manager thought, because the New England area had given a very favorable response to the Born in the U.S.A. Tour.)[34] Two shows in Cleveland's Richfield Coliseum sold out in four hours.[65] Indeed, there were quick sellouts all across the eastern U.S. and elsewhere.[67][69]

How much the tour grossed overall is unclear. For the years 1987 and 1988 combined, Forbes magazine estimated that Springsteen earned $61 million from all sources, and for the years 1988 and 1989 combined, $40 million.[70]

Reviews of the Tunnel of Love Express were generally favorable, with some more mixed views.

The Associated Press found the opening Worcester shows full of "twists and turns" that at first "befuddled the crowd with an assortment of seldom-heard songs" before he "eventually put the crowd in a frenzy."[17] The Blade newspaper of Toledo, Ohio declared that "there is much new and much different about the 'Tunnel of Love' tour. There are new songs, and new insights to be gained from old ones."[23] The Milwaukee Journal found that the obscure and unexpected songs in the set list were the show's best moments, but also said that "at times, the new horn section proved to be unneeded baggage", either diluting or drowning out the rest of the band.[14]

Jon Pareles of The New York Times found the show undermined by the didactic, monochromatic nature of Springsteen's more recent songs.[33] Stephen Holden of the same paper, on the other hand, thought those same songs "wonderful", and wrote that "In concert, [Springsteen has] figured out how to string songs into extended journeys that take on a cumulative power as the evening proceeds."[29] He concluded that "Springsteen reconciles seemingly unreconcilable concepts: a sober awareness of social and erotic realities and a boundless faith in life."[29] (Holden's review itself became suspect due to his describing performances of songs not actually played.[71])

The Spokane Chronicle said that with the addition of the horn section, "the always powerful E Street Band is more muscular than ever" and that thematically, the show takes the viewer "for a bleak ride before you reach the light of day."[18] Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times assayed that Springsteen "stepped away from the two concert elements that have most been associated with him – spontaneity and celebration – to concentrate on artistic independence and growth."[20] The result, Hilburn stated, were Springsteen's "most studied, yet most radical and liberating appearances yet".[20]

The Glasgow Herald stated that the first-set performances of John Lee Hooker's (by way of The Animals) "Boom Boom" as well as the Bo Diddley-inspired "Ain't Got You"/"She's the One" were the high points of the Birmingham concert at Villa Park but that overall the show lacked genuine geographical or thematic connection with its British audience.[72] The Swedish newspaper Aftonbladet claimed that the second and third parts of the show were the greatest rock show ever put forth on Swedish ground.[73]

Legacy

[edit]In all, the Tunnel of Love Express lacked the athletic, boisterous liveliness that Springsteen had been known for, and featured largely fixed and predetermined performances and on-stage banter.[9] Bassist Tallent would say a couple of decades later,

The Tunnel of Love Express tour was unlike anything we'd ever done in that so much of it was staged. The band had fixed positions onstage; unlike every other time we performed live, there was really no spontaneity. We had our parts and needed to stick to them if the show was going to make any sense.[11]

Springsteen biographer Marsh would write in 2006, "As a tour, Tunnel of Love Express presents the greatest puzzle of Springsteen's career."[1] In his 2016 memoir, Springsteen wrote of the tour, "After Born in the USA, it was an intentional left turn and the band was probably somewhat disoriented by it, along with my growing relationship with Patti."[12] Of the split with Phillips, he wrote, "I dealt with Julie's and my separation abysmally, insisting it remain a private affair, so we released no press statement, causing furor, pain and 'scandal' when the news leaked out. It made a tough thing more heartbreaking than necessary. I deeply cared for Julianne and her family and my poor handling of this is something I regret to this day."[74]

In any case, rearranging where the band members stood on stage did not change things enough for Springsteen.[75] The August 4, 1988, show in Barcelona that closed out the Tunnel of Love Express would be the last full-length Springsteen and E Street Band show for eleven years. Following the Human Rights Now! Tour later that year, which featured abbreviated sets and few performances of Tunnel of Love songs, Springsteen broke up the E Street Band. It would not tour again until the 1999–2000 Reunion Tour.[9] The staged aspects of the tour would not appear again, and its songs would remain infrequently performed.

Broadcasts and recordings

[edit]MTV filmed the March 28 show in Detroit's Joe Louis Arena. Portions of several songs were aired as part of their special Bruce Springsteen – Inside the Tunnel of Love on April 30.[76] And as noted earlier, much of the July 19 East Berlin concert was broadcast live on GDR state television and radio.[38]

The first set of the July 3 show in Stockholms Olympiastadion was broadcast live on radio to an international audience. Distributed through D.I.R. Broadcasting and available free to any station that wanted it, it was Springsteen's first live broadcast since 1978, and the first available nationwide.[77] Some 300 stations broadcast it in the United States, and it was also heard across Canada, Europe, Australia, and Japan.[77] Proceeds from commercials that aired before and after the concert segment were to be divided between DIR and Springsteen, and after subtraction for costs, sent to charity.[77] The set itself followed tour practice except for the addition of Bob Dylan's "Chimes of Freedom" at the close, as Springsteen announced his upcoming participation in Amnesty International's Human Rights Now! Tour later that year.[78] The Chimes of Freedom EP, released in August 1988, included that rendition, as well as documenting three other song performances from scattered dates on the Express, including the radical simplification of "Born to Run".

Several shows from the tour have subsequently released via the Bruce Springsteen Archives or similar mechanisms. In July 2015, Springsteen released LA Sports Arena, California 1988, the first official full show live release from this tour. It captured the April 23 show performed at the Los Angeles Sports Arena and was available through his website.[79] This would be followed by the release of the July 3 show in Stockholm in November 2017, the release of the May 23 U.S. leg finale at Madison Square Garden in January 2019, the March 28 show from Detroit in March 2020, the fifth and final show at the Los Angeles Sports Arena in April 2021 & the first night at Madison Square Garden in May 2022.

Personnel

[edit]The E Street Band

[edit]- Bruce Springsteen – lead vocals, guitars, harmonica

- Roy Bittan – piano, synthesizer

- Clarence Clemons – saxophone, congas, percussion, background vocals

- Danny Federici – organ

- Nils Lofgren – guitars, background vocals

- Patti Scialfa – background vocals, some featured duet vocals, acoustic guitar, percussion

- Garry Tallent – bass guitar

- Max Weinberg – drums

The Horns of Love

[edit]- Mario Cruz – saxophone

- Eddie Manion – saxophone

- Mark Pender – trumpet

- Richie "La Bamba" Rosenberg – trombone

- Mike Spengler – trumpet

Tour dates

[edit]| Date | City | Country | Venue | Attendance | Revenue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | |||||

| February 25, 1988 | Worcester | United States | The Centrum | 38,233 / 38,233 | $762,060 |

| February 28, 1988 | |||||

| February 29, 1988 | |||||

| March 3, 1988 | Chapel Hill | Dean Smith Center | 40,158 / 40,158 | $801,200 | |

| March 4, 1988 | |||||

| March 8, 1988 | Philadelphia | The Spectrum | 37,296 / 37,296 | $741,680 | |

| March 9, 1988 | |||||

| March 13, 1988 | Richfield | Richfield Coliseum | 37,644 / 37,644 | $752,880 | |

| March 14, 1988 | |||||

| March 16, 1988 | Rosemont | Rosemont Horizon | 35,632 / 35,632 | $801,720 | |

| March 17, 1988 | |||||

| March 20, 1988 | Pittsburgh | Civic Arena | 16,969 / 16,969 | $381,802 | |

| March 22, 1988 | Atlanta | The Omni | 32,944 / 32,944 | $741,218 | |

| March 23, 1988 | |||||

| March 26, 1988 | Lexington | Rupp Arena | 23,134 / 23,134 | $520,515 | |

| March 28, 1988 | Detroit | Joe Louis Arena | 39,550 / 39,550 | $889,875 | |

| March 29, 1988 | |||||

| April 1, 1988 | Uniondale | Nassau Coliseum | 37,760 / 37,760 | $782,100 | |

| April 2, 1988 | |||||

| April 4, 1988 | Landover | Capital Centre | 36,333 / 36,333 | $820,396 | |

| April 5, 1988 | |||||

| April 12, 1988 | Houston | The Summit | 34,128 / 34,128 | $690,713 | |

| April 13, 1988 | |||||

| April 15, 1988 | Austin | Frank Erwin Center | 17,190 / 17,190 | $386,190 | |

| April 17, 1988 | St. Louis | St. Louis Arena | 18,532 / 18,532 | $416,408 | |

| April 20, 1988 | Denver | McNichols Arena | 17,660 / 17,660 | $397,350 | |

| April 22, 1988 | Los Angeles | Los Angeles Sports Arena | 77,734 / 77,734 | $1,749,015 | |

| April 23, 1988 | |||||

| April 25, 1988 | |||||

| April 27, 1988 | |||||

| April 28, 1988 | |||||

| May 2, 1988 | Mountain View | Shoreline Amphitheatre | 20,105 / 20,105 | $422,205 | |

| May 3, 1988 | 20,123 / 20,123 | $422,583 | |||

| May 5, 1988 | Tacoma | Tacoma Dome | 47,642 / 47,642 | $1,071,945 | |

| May 6, 1988 | |||||

| May 9, 1988 | Bloomington | Met Center | 34,795 / 34,795 | $782,888 | |

| May 10, 1988 | |||||

| May 13, 1988 | Indianapolis | Market Square Arena | 17,577 / 18,154 | $395,483 | |

| May 16, 1988 | New York City | Madison Square Garden | 98,458 / 98,458 | $2,215,305 | |

| May 18, 1988 | |||||

| May 19, 1988 | |||||

| May 22, 1988 | |||||

| May 23, 1988 | |||||

| Europe | |||||

| June 11, 1988 | Turin | Italy | Stadio Comunale di Torino | 65 000 | |

| June 15, 1988 | Rome | Stadio Flaminio | 40 000 | ||

| June 16, 1988 | 40 000 | ||||

| June 19, 1988 | Paris | France | Hippodrome de Vincennes | 80 000 | |

| June 21, 1988 | Birmingham | England | Villa Park | 40 000 | |

| June 22, 1988 | 40 000 | ||||

| June 25, 1988 | London | Wembley Stadium | 80 000 | ||

| June 28, 1988 | Rotterdam | Netherlands | Feyenoord Stadion | 100 000 | |

| June 29, 1988 | |||||

| July 2, 1988 | Stockholm | Sweden | Stockholm Olympic Stadium | 33 000 | |

| July 3, 1988 | 33 000 | ||||

| July 7, 1988 | Dublin | Ireland | RDS Arena | 43 000 | |

| July 9, 1988 | Sheffield | England | Bramall Lane | 44 000 | |

| July 10, 1988 | 44 000 | ||||

| July 12, 1988 | Frankfurt | West Germany | Waldstadion | 51 400 | |

| July 14, 1988 | Basel | Switzerland | St. Jakob Stadium | 55 000 | |

| July 17, 1988 | Munich | West Germany | Olympia Reitstadion Riem | 35 000 | |

| July 19, 1988 | East Berlin | East Germany | Radrennbahn Weissensee | 500 000 | |

| July 22, 1988 | West Berlin | West Germany | Waldbühne | 23 000 | |

| July 25, 1988 | Copenhagen | Denmark | Idraetsparken | 58 000 | |

| July 27, 1988 | Oslo | Norway | Valle Hovin | ||

| July 30, 1988 | Bremen | West Germany | Weserstadion | 45 000 | |

| August 2, 1988 | Madrid | Spain | Vicente Calderón Stadium | 62 000 | |

| August 4, 1988 | Barcelona | Camp Nou | 90 000 | ||

Songs performed

[edit]|

The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle

|

Other

|

|

|

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Alterman, Eric (2001). It Ain't No Sin To Be Glad You're Alive: The Promise of Bruce Springsteen. Back Bay. ISBN 0-316-03917-9.

- Cavicchi, Daneil (1998). Tramps Like Us: Music & Meaning among Springsteen Fans. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511833-2.

- Derkins, Susie (2002). Rock & Roll Hall of Famers: Bruce Springsteen. New York: Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8239-3522-1.

- Guterman, Jimmy (2005). Runaway American Dream: Listening to Bruce Springsteen. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81397-1.

- Marsh, Dave; Bernard, James (1994). The New Book of Rock Lists. New York: Fireside Books. ISBN 0-671-78700-4.

- Marsh, Dave (2006). Bruce Springsteen On Tour: 1968–2005. New York: Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 1-59691-282-0.

- Masur, Louis P. (2009). Runaway Dream: Born to Run and Bruce Springsteen's American Vision. New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-60819-101-7.

- Santelli, Robert (2006). Greetings From E Street: The Story of Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-5348-9.

- Springsteen, Bruce (2016). Born to Run. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-5011-4151-5.

- Symynkywicz, Jeffery B. (2008). The Gospel According to Bruce Springsteen: Rock and Redemption, from Asbury Park to Magic. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-23169-9.

- Wiersema, Robert J. (2011). Walk Like a Man: Coming of Age with the Music of Bruce Springsteen. Vancouver: Greystone Books. ISBN 978-1-55365-845-0.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Marsh, Bruce Springsteen On Tour, p. 172.

- ^ a b c Marsh, Bruce Springsteen On Tour, p. 175.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hilburn, Robert (March 2, 1988). "Springsteen plays few hits on 'Tunnel of Love' tour". Anchorage Daily News. Los Angeles Times. p. G-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Pond, Steve (May 5, 1988). "Bruce Springsteen's Tunnel Vision". Rolling Stone. Cover story.

- ^ a b c Symynkywicz, The Gospel According to Bruce Springsteen, p. 105.

- ^ "Springsteen tour begins in February". Milwaukee Sentinel. January 7, 1988. p. 3.

- ^ Derkins, Bruce Springsteen, p. 70.

- ^ "El primer concierto de Bruce Springsteen en España". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Barcelona. April 21, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Derkins, Bruce Springsteen, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Cavicchi, Tramps Like Us, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e Santelli, Greetings From E Street, pp. 76-77.

- ^ a b c d Springsteen, Born to Run, p. 350.

- ^ a b Guterman, Runaway American Dream, p. 173.

- ^ a b c d Christensen, Thor (March 17, 1988). "Bruce grows up without growing old". The Milwaukee Journal. p. 5B.

- ^ McShane, Larry (November 24, 1991). "Jersey shore reunion for Southside Johnny". Hudson Valley News. Associated Press. p. A4.

- ^ Marsh, Bruce Springsteen On Tour, pp. 45–46, 178.

- ^ a b c d e McShane, Larry (March 1, 1988). "Strange twists appearing in Springsteen's tour". Spartanburg Herald-Journal. Associated Press. p. D8.

- ^ a b c Adair, Don (May 6, 1988). "Springsteen in Tacoma: It's a ride in the 'Tunnel of Love'". Spokane Chronicle. p. 5.

- ^ a b Wiersema, Walk Like a Man, p. 87.

- ^ a b c d e Hilburn, Robert (May 10, 1988). "Springsteen opening new door with tour". The Eugene Register-Guard. Los Angeles Times. p. 6A.

- ^ a b c d e Guterman, Runaway American Dream, p. 174

- ^ a b c d e f g h Marsh, Bruce Springsteen On Tour, p. 178.

- ^ a b c d e Ford, Tom (March 20, 1988). "Bruce, Bruce, Bruce". The Blade. Toledo. p. E1.

- ^ a b c Marsh, Bruce Springsteen On Tour, p. 182.

- ^ a b c Marsh, Bruce Springsteen On Tour, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Cavicchi, Tramps Like Us, p. 86.

- ^ a b c d e f g Williams, Stephen (April 1, 1988). "Springsteen a Steamy Hit in Detroit". Newsday.

- ^ a b Hinckley, David (August 22, 1998). "How the Boss Lost His Halo". Us. p. 16.

- ^ a b c Holden, Stephen (May 17, 1998). "Springsteen at the Garden". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e f Guterman, Runaway American Dream, p. 175

- ^ a b Masur, Runaway Dream, pp. 160–161.

- ^ a b Marsh, Bruce Springsteen On Tour, p. 183.

- ^ a b Pareles, Jon (February 27, 1988). "Springsteen Starts First Tour in 2 Years". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d "Boss fans' patience rewarded". The Bulletin. Bend, Oregon. United Press International. February 7, 1988. p. E10.

- ^ "Names in the News". The Durant Daily Democrat. Associated Press. July 13, 1988. p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Connolly, Kate (July 5, 2013). "The night Bruce Springsteen played East Berlin – and the wall cracked". The Guardian. London.

- ^ a b c d Purschke, Thomas (July 16, 2018). "Bruce Springsteen in Ost-Berlin im Juli 1988: Die Stasi hörte mit". Leipziger Volkszeitung (in German).

- ^ a b c d "More than 100,000 East German fans see Springsteen". The Lewiston Journal. Associated Press. July 21, 1988. p. 8D.

- ^ a b c d e Alterman, It Ain't No Sin To Be Glad You're Alive, pp. 247-248.

- ^ a b c Derkins, Bruce Springsteen, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Ayed, Nahlah (November 6, 2014). "How a Bruce Springsteen concert helped bring down the Berlin Wall". CBC News.

- ^ A fan present is said to have written: "19th of July 1988: Bruce played over 4.5 hours in East Berlin, we're there to celebrate him, I paid lousy 19.95 east marks for my ticket but what I really bought and got was a glimpse to freedom. I smelled the American spirit that night and I'll never forget it!"

- ^ Wünsch, Silke (November 6, 2019). "Bruce Springsteen: An icon of freedom in East Germany". Deutsche Welle.

- ^ a b c d e Hilburn, Robert (June 19, 1988). "Does album really reflect if marriage is going down?". Asbury Park Press. Los Angeles Times. Date is approximate.

- ^ a b c d Gundersen, Edna (June 23, 1988). "Fans: Affair only proves he's human". USA Today. p. 1D.

- ^ a b c d e f Trebbe, Ann (June 20, 1988). "It's official: Bruce, wife no longer a duet". USA Today. p. 1D.

- ^ "Patti pounds it out on tour with Bruce". USA Today. April 19, 1988. p. 2D.

- ^ a b Infusino, Divina (November 18, 1988). "Springsteen Latest To Face Media Backlash". Copley News Service. p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e Marsh, Bruce Springsteen On Tour, p. 187.

- ^ Wiersema, Walk Like a Man, p. 92.

- ^ a b "Are Bruce and Julianne splitting?". Toronto Star. May 29, 1988. p. D2.

- ^ Takiff, Jonathan (June 23, 1988). "The honeymoon is over ... Marriage no longer music to Springsteens' ears". Boca Raton News. Knight-Ridder Newspapers. p. 1W.

- ^ a b c d Van Buskirk, Leslie (August 22, 1998). "Starting Over". Us. pp. 12–16.

- ^ a b c d Gundersen, Edna (June 28, 1988). "Finally, Bruce's official word on the breakup". USA Today. p. 1D.

- ^ "Was Bruce really born to run?". USA Today. June 23, 1988. p. 1D. Photographs.

- ^ a b Willman, Chris (July 11, 1993). "Speaking Up in Her Own Voice". Los Angeles Times. p. 4.

- ^ "Boss' New Beat". New York Daily News. June 22, 1998. p. 19. Photograph.

- ^ a b c d Byron, Ellen (August 1989). "The Boss and his midlife crisis". Woman's World. pp. 32–33. Date is approximate.

- ^ a b Goldfarb, Michael (June 27, 1988). "Bruce and Patti? It's hard to tell". USA Today. p. 2D.

- ^ a b c d e Graff, Gary (July 3, 1988). "Springsteen marriage woes have some distraught, others ambivalent". The Vindicator. Youngstown, Ohio. Knight-Ridder Newspapers. p. D18.

- ^ Dawidoff, Nicholas (January 26, 1997). "The Pop Populist". The New York Times Magazine.

- ^ Cavicchi, Tramps Like Us, p. 32.

- ^ Guterman, Runaway American Dream, p. 176.

- ^ a b c d Moyers, Cope (April 3, 1988). "Hey, What's $100?' Supply meets demand at Springsteen concerts". Newsday. p. 3.

- ^ a b "Springsteen fans pack Coliseum". The Bryan Times. Associated Press. March 16, 1988. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Concert is 2-hour sell out". The Modesto Bee. February 15, 1988. p. A2.

- ^ a b Moyers, Cope (March 4, 1988). "No Tickets, but Sales Are Hot". Newsday. p. 7.

- ^ "Boss fanatics mount write-in". Rome News-Tribune. Associated Press. March 4, 1988. p. 10A.

- ^ Gundersen, Edna (March 14, 1988). "Bruce adds 6 new stops". USA Today. p. 1D.

- ^ Marsh and Bernard, The New Book of Rock Lists, pp. 25–26.

- ^ "Just a Tiny Detail". Newsday. May 18, 1988. p. 6. Archived from the original on June 30, 2013.

- ^ Belcher, David (June 23, 1988). "Villa Park, Birmingham: Bruce Springsteen". The Glasgow Herald. p. 4.

- ^ Peterson, Jens (July 3, 1988). "unclear". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Stockholm. For a later use of this review, see Steen, Håkan (June 23, 1999). "Alla svenska gig". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Stockholm.

- ^ Springsteen, Born to Run, p. 351.

- ^ Masur, Runaway Dream, p. 160.

- ^ "Rock News & Notes". Daily News of Los Angeles. April 29, 1988.

- ^ a b c Jensen, Elizabeth (July 1, 1988). "Boss says thanks in big way". New York Daily News. p. 98.

- ^ Marsh, Bruce Springsteen On Tour, p. 188.

- ^ "Los Angeles Sports Arena Los Angeles, CA". Brucespringsteen.net. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ "Bruce Springsteen Setlists | Greasy Lake". Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ "Brucebase - home". brucebase.wikispaces.com. Retrieved April 19, 2018.