Tsaritsyno Palace

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Царицыно | |

| |

| Established | 1775 |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 55°36′54″N 37°40′55″E / 55.61500°N 37.68194°E |

Tsaritsyno (Russian: Царицыно, IPA: [tsɐˈrʲitsɨnə], literal meaning "Tsaritsa's property") is a palace museum and park reserve in the south of Moscow.

It was founded in 1775 as the summer residence of Empress Catherine II, but the construction remained incomplete. For most of its history, it was a half-abandoned park with picturesque ruins. In the 2000s, the palace was restored according to the original plans. Today, it is a museum complex and a leisure place for Muscovites and tourists.[1]

History

[edit]During the Russian Empire

[edit]Before Catherine the Great

[edit]The land has been packaged together since the 16th century under Bogorodskoye, when it belonged to Tsaritsa Irina, sister of Tsar Boris Godunov. Over two centuries, it changed hands between several noble owners (including Streshnevs and Galitzines) until Catherine the Great finally bought it from the former owner, Prince Cantemir, in 1775.[2]

During the time of Catherine the Great

[edit]Catherine the Great wished to use the estate as a summer residence. An essential role in the future fate of Tsaritsyno was played by the fact that it is located in an area that, at that time, was a suburb of Moscow. In the same year, the empress gave the task to her court architect, Vasily Bazhenov, to develop a project for a summer residence near Moscow.

Bazhenov's project

[edit]Bazhenov designed the palace in the Neo-Gothic, Moscow Baroque, and Classical styles. He planned Tsaritsyno as a complete mini town:.

The peculiarity of the layout of the Tsaritsyno buildings is such that it allows us to speak of the "poetry of geometry": with the use of symmetry and different geometric shapes embedded in the design. Six octahedrons pavilions are laid in a cruciform; The Small Palace is in the form of a semicircle; the Kitchen Building is in the form of a square with rounded corners. The same applies to the internal layout: round, oval, and semi-oval halls are masterfully combined with rectangular halls. It is important to note that Bazhenov designed almost all the interiors of the Tsaritsyno buildings with vaulted ceilings, which achieved an even more significant effect of the play on geometric shapes.[3]

One of the main features of Bazhenov's project was that there was no main palace as a single building - there are instead three independent buildings. Catherine II liked the project, and construction began in May 1776.

However, by the end of the year, troubles arose with building supplies and funding; this was repeated several times throughout the construction, which lasted for a decade - contrary to the architect's plans to finish it all in three years. Bazhenov wrote numerous letters to officials to determine the reasons for the difficulties. Nevertheless, despite money and material shortages, the previously begun buildings were completed in 1777-1778, and in 1777 the construction of the Figured Gate and the main palace, which consisted of three buildings, began. It ended in 1782; at the same time, work for the Large Cavalry Corps, several outbuildings, and an arch-gallery was started.

In early June 1785, ten years after the beginning of construction, Catherine II arrived in Moscow. The visit was brief. She briefly inspected the palace and left it very disappointed. The verdict of the empress after a quick inspection was harsh: the money spent on construction could have been better spent, the stairs were narrow, the ceilings were heavy, the rooms and boudoirs were cramped, and the halls were dark, like cellars. Catherine ordered "to make a fair amount of deconstruction" and to present a new project for the main palace.

Historians now agree the main reason is that by the year 1785 Bazhenov's palace layout became politically incorrect: relations between Catherine and Crown Prince Paul irreversibly worsened, the empress had thoughts of removing Paul from the order of succession completely, and twin palaces had to make way for a single one – her own. Another reason for the royal anger could be Bazhenov's affiliation with the Freemasons (the architect underwent an initiation ceremony in 1784 on the guarantee of the educator and publisher N.I. Novikov, and was admitted to the Deucalion lodge), and his secret contacts with Tsarevich Pavel Petrovich.

Bazhenov's freemasonry was highly reflected in the Tsaritsyno buildings. The decor of many buildings, the mysterious lacy stone patterns, clearly resemble Masonic ciphers and emblems. Tsaritsyno is often referred to as the "architectural reference book" of Masonic symbols of the 18th century.

Bazhenov was immediately removed from construction, his student, Matvey Kazakov, was appointed the new architect of the Tsaritsyno residence, which was another humiliation for the retired architect. The Empress ordered Kazakov to build a new palace as a single building. More than six months passed after Catherine II's inspection of the Tsaritsyno before a new project for palace development was approved.

Kazakov's Big Palace

[edit]By February 1786, Kazakov prepared a project for the Grand Palace, and it was approved by the Empress. In March, the dismantling of two buildings began - the chambers of Catherine and Tsarevich Pavel. In November 1796, Catherine the Great suddenly died. At this time, the construction of the Grand Tsaritsyno Palace had been roughly completed. The building was covered with a temporary roof. Interior finishing work had begun; when all work in Tsaritsyno was stopped, 17 rooms of the Big Palace had parquet floors and ceilings. In the remaining Bazhenov buildings no interior decoration was carried out for the entire previous decade. The new Emperor Paul I visited Tsaritsyno after his coronation in March 1797 and did not like it. On June 8 (19) of the same year, a decree was issued "not to produce any buildings in the village of Tsaritsyno." In the future, the development of the Tsaritsyno buildings did not resume, and the palace ensemble, so long and difficult to build for Vasily Bazhenov and Matvey Kazakov, never became a residential imperial residence.

Imperial residence after Catherine

[edit]

The unfinished royal residence quickly fell into disrepair. Already at the very beginning of the 19th century, buildings began to collapse and overgrow with greenery like classical ruins.

The emperors following Catherine were not particularly interested in Tsaritsyno, did not live there, and did not try to complete the construction.

However, starting from the reign of Alexander I, Tsaritsyno Park became available for "promenades".

However, the first decade of the 19th century in Tsaritsyno is associated with the activities of P. S. Valuev, the head of the "Kremlin Expedition of Buildings", and I. V. Egotov, a student of Bazhenov and Kazakov, who was the director of the "Kremlin Drawing Expedition" since 1803. Under the leadership of Ivan Egotov, the design of a landscape park was completed: instead of several wooden Bazhenov pavilions, stone park pavilions and gazebos (Milovida, Nerastankino, Temple of Ceres) were built.

Finally, in 1860, after an audit that admitted that the maintenance of the estate did not bring significant income, Tsaritsyno was transferred from the department that managed the royal property to the Department of Appanages. Thus, Tsaritsyno ceased to be the personal property of the imperial family.

Becoming a state property: Tsaritsyno-Dachnoe

[edit]

After becoming state property, Tsaritsyno was meant to generate income. At first, it was supposed to sell all the buildings for demolition for 82,000 rubles, but no buyer was found. At the same time, Moscow authorities decided to lease out part of the Tsaritsyno lands for dacha development. The idea was hampered by the lack of transport links with Moscow, but the situation changed in 1865 when the "Tsaritsyno'' station of the newly built Kursk railway was opened (it was even renamed to Tsaritsyno-Dachnoye in 1904). The plans for dacha development mainly affected the territories located to the west of the palaces and the historical park but part of the palace estate was also given over to dachas. This part included the First and Third Cavalier Corps with the adjacent palace territories, as well as the fields with greenhouses and orchards from the east.

Tsaritsyno became a holiday destination; in the 1870s, a whole summer cottage village Novoe Tsaritsyno came into existence. Over the years, celebrities rented dachas here or visited friends and relatives: writers F. M. Dostoevsky, F. I. Tyutchev, A. N. Pleshcheev, A. P. Chekhov, I. A. Bunin (here he met his future second wife, Vera Muromtseva), Leonid Andreev, Andrei Bely, N. D. Teleshov, composers M. A. Balakirev and P. I. Tchaikovsky, historians I. E. Zabelin and V. O. Klyuchevsky, naturalist K. A. Timiryazev, Chairman of the First State Duma S. A. Muromtsev. By the beginning of the 20th century, there were about a thousand dachas in Tsaritsyno and nearby villages, despite the fact that those dachas were considered extremely expensive.[4]

The condition of the ownerless palace buildings steadily worsened. Abandoned greenhouses were demolished; some buildings and pavilions were occasionally used, and so underwent cosmetic repairs. But most of the buildings were still in disrepair. In 1880 there was a partial collapse of the roof of the Grand Tsaritsyno Palace; in order to avoid accidents, it was decided to remove the remnants of the roof and dismantle the frames of the Gothic décor of the towers.

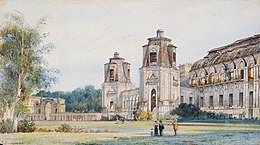

- Ruined state of the Grand Palace at the turn of the 20th century

-

Tsarytsyno Palace Panorama. 1888. Before the roof collapsed.

-

Postcard. Tsaritsyno Grand Palace. Beginning of the 20th century. After the roof collapsed.

During the years of the Soviet Union

[edit]In the first years of Soviet power, the Tsaritsyno, along with New Tsaritsyno and the nearest villages were combined under the name of Lenino village.

Created in March 1918, the revolutionary local government - the Soviet of Workers', Peasants' and Soldiers' Deputies, - was located in the First Cavalry Corps. In 1932, this building was rebuilt and became a 3-story building (the brick for completion was taken from the inner walls of the adjacent Second Cavalry Corps); it housed the executive committee of the Leninsky district of the Moscow region.

First Museum

[edit]In 1926, the palace and park ensemble was transferred to the jurisdiction of Glavnauka, and after - to the museum sub-department of Moscow Department of Public Education. On July 21, 1927, the Tsaritsyno Museum was opened in the building of the Third Cavalry Corps; a year later, the museum acquired the status of a local history museum. The first repair and restoration work in Tsaritsyno also dates back to 1927.

However, the museum did not last long in this form. In 1930, in accordance with the collectivization campaign, the exposition was based on models of agricultural products and diagrams of the development of the Leninsky district; the museum itself began to be called the "Leninsky District Local Horticultural and Garden Museum". Finally, in 1937 the museum was closed, and the village club with a cinema was set up in the building.

Maintenance during Soviet Era

[edit]The Khlebny Dom received a new life in Soviet times: in the early 1920s, communal apartments spontaneously appeared here. They lasted until the 1970s. In 1939, the temple on the territory of the palace and park ensemble was closed; the building was given over to host a transformer substation.

In 1936, by the order of the Moscow City Council, architects developed a project for adapting the Tsaritsyno ensemble into a rest house. The implementation of these plans was halted by the Great Patriotic War.

At the end of the 1950s, the Milovida and Nerastankino pavilions, the Golden Sheaf pavilion, and a number of park bridges again required restoration. The work was carried out in 1958-1961. The first project of the scientific restoration of the Tsaritsyno architectural and landscape monuments dates back to the end of the 1960s.

In 1960, Lenino became part of Moscow. In the 1970s, because of the development of the nearby Orekhovo-Borisovo residential area, a security zone with an area of more than 1,000 hectares was established around Tsaritsyno and the cascade of the Tsareborisovsky Ponds.

Restoration at the end of the 20th - beginning of the 21st century

[edit]Since the mid-1980s, scientific restoration of the Tsaritsyno objects has been carried out; almost all of them were restored by 2004.

In 2004, the museum-reserve was transferred under the jurisdiction of the Moscow authorities, and in September 2005, full-scale work was launched in Tsaritsyno to restore the Grand Palace and reconstruct the palace ensemble and park. The reconstruction project was developed in the architectural workshop No. 13 "Mosproekt-2" (the authors of the project are O. E. Galanicheva, N. G. Mukhin) under the leadership of Moscow Mayor Yu. M. Luzhkov and the head of "Mosproekt-2" M. M. Posokhin.

However, the Tsaritsyno reconstruction work caused an intense debate, which lasted throughout the implementation of the project. Critics of the project, among whom were prominent art critics, restorers, and architects, noted that the new Tsaritsyno construction was carried out with violations of the legislation of protection of cultural monuments, and with unacceptable distortions of the historical appearance of Tsaritsyn. The idea of building an atrium in the Khlebny Dom came under criticism: the project supposed the construction of a glass-domed ceiling of the courtyard, which changed the silhouette of the building.

The greatest objections were raised by the project of restoration of the Grand Palace. This idea itself, according to critics, was erroneous: from the standpoint of preserving historical authenticity; it is impossible to restore what was destroyed in a natural way; you cannot finish building something that was not completed due to historical circumstances. Architectural historian Grigory Revzin pointed out that back in the 19th century, the ruins of the Grand Tsaritsyno Palace were a self-sufficient monument, belonging to the era of romanticism, in which there was a cult of ruins. The dilapidated palace was an important part of the landscape park, forming a special emotional atmosphere around it. Dmitry Shvidkovsky, rector of the Moscow Institute of Architecture, also noted that the completion of the construction essentially destroyed the monument, since the perception of the building radically changed.

The next objection of the opponents of the project was related to the appearance of the palace: if it was to be restored, then only strictly adhering to the principles of scientific restoration. Yet the project was supposed to build the palace in a form in which it never existed. During the original construction of the palace, in 1793, according to the order of Catherine II, Matvey Kazakov made changes: the palace was lowered by one floor and obtained different roofs of the main buildings and towers. The Mosproekt-2 project combined both options - the actually existing walls of the final Kazakov version of the palace were planned to be completed with roofs from the original, unrealized version. Aleksey Komech, director of the Institute of Art Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences and a consistent opponent of the plans to restore the palace, called this approach "fantasy restoration". As an alternative to "fake" and "remake", it was proposed to emphasize the authenticity of the ruined palace with the help of modern architectural technologies: for example, by placing some glass rooms inside the conserved ruins that could be used for museum purposes. One such project for the restoration of the palace was developed and approved shortly before the Tsaritsyno ensemble became the property of Moscow.[5]

In response to critics, the Moscow authorities referred to the opinion of Muscovites: according to sociological surveys, residents of the Tsaritsyno district wanted to see the palace restored. M. M. Posokhin noted that the roof of the palace, which existed for about a hundred years, was temporary and was erected at the end of the 18th century by order of the then Moscow authorities in order to preserve the building. Therefore, it cannot be considered the author's intention.

Experts also criticized the newly-built objects, that did not previously exist: a transformer box in the Gothic style, a glass pavilion leading to the underground lobby of the museum, a light-dynamic fountain on the Middle Tsaritsyno pond (it was noted that Catherine II did not love fountains).

Opponents of the reconstruction, seeing that their arguments were being ignored by the project leaders, appealed to Rosokhrankultura and the Prosecutor General's Office of the Russian Federation with a demand to stop the construction as violating the current legislation of cultural heritage protection, but to no avail. A. I. Komech, the initiator of the appeals, assumed the following outcome to be very likely:

"We will not be heard, but we still need to talk about preserving history, otherwise it will be even worse."

Despite severe criticism from a number of experts, the restoration project of the Grand Tsaritsyno Palace was fully finished in 2005-2007. In a short time, a huge amount of construction and restoration work was carried out; much of which was unique. The official opening of the reconstructed palace complex, including the restored Grand Tsaritsyno Palace, took place on September 2, 2007. The President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin took part in the celebration.

The main attractions of Tsaritsyno

[edit]Palace ensemble

[edit]Bazhenov's buildings

[edit]It consists of more than 20 buildings, most of which were built by the architect Bazhenov in 1775 - 1785 and give Tsaritsyno its recognizable appearance. All of them were built in Moscow Baroque and Neo-Gothic style. It is also claimed that the decoration of the buildings includes many Masonic symbols (Bazhenov was a Freemason), and the meaning of many of them is still not solved.

- Some of Bazhenov's building in Tsaritsyno

-

Khlebnyi Dom (Bread House)

-

Bazhenov's Figured Bridge

-

Bazhenov's Big Bridge over the Ravine

-

Bazhenov's Opera House (Medium Palace)

-

Bazhenov's Small Palace

-

Bazhenov's Second Cavalier Corps

-

Bazhenov's Grape Gates.

Kazakov's Big Palace

[edit]However, the largest building of the complex - the Grand Palace - was designed by Bazhenov's student, Matvey Kazakov. Construction began under the command of Kazakov in 1786, but was not fully completed. The unfinished palace stood half-ruined for more than 200 years. It was finished only in 2007 by architectural restorers according to historical drawings.

- Tsaritsyno Big Palace by the project of Matvey Kazakov

Later buildings

[edit]Many small architectural forms, pavilions, "picturesque ruins" in the park were erected in the 19th century, in the era of romanticism. This happened after Tsaritsyno ceased to be a personal royal residence and became a public park.

-

Nerastankino Pavilion

-

Ceres Temple

-

Grotesque bridge

Park and ponds

[edit]The Tsaritsyno palace and park ensemble, covering an area of more than 100 hectares, is located on a hilly area crossed by ravines.

Park

[edit]

The park began to be arranged in the 1770s, simultaneously with the beginning of the palace construction.

Vyatichi's burial mounds

[edit]The place where Tsaritsyno is located was inhabited long before Catherine's reign. One of the first inhabitants was the East Slavic tribe of Vyatichi between the 9th and 12th centuries.

In the depths of the Tsaritsyno park, their burial mounds are still preserved. They attracted the attention of historians and archaeologists as early as the 19th century. The most complete archaeological excavations date back to 1944. A group led by A.V. Artsikhovsky discovered a number of interesting items, including tools, which until then had not been found in similar burial mounds in the Moscow region. The findings were subsequently transferred to the Tsaritsyno Museum-Reserve and laid the foundation for its archaeological collection.[6][7]

Ponds and islands

[edit]

The Tsaritsynskiye ponds cascade was formed during the 16th-18th centuries. The oldest is the Borisovsky pond, which was founded during the reign of Boris Godunov. The upper and lower Tsaritsynskiy ponds appeared when the estate of Chernaya Gryaz belonged to the boyars Streshnevs: the lower pond appeared in the 17th century. All the subsequent owners of the Chyornaya Gryaz paid a lot of attention to maintaining the ponds, building and reconstructing dams, water mills, and creating artificial islands. The Middle Tsaritsynsky Pond appeared in the 1980s after the construction of a high dam, along which the route of Novotsaritsynsky Highway divided the Lower Pond into two parts. Directly adjacent to the Grand Palais and park ensemble are the Upper and Middle ponds. They form a natural boundary of the ensemble from the west and an important part of it. Some of the palace buildings and pavilions of the landscape park are oriented towards the ponds.[8]

Fountain

[edit]During the 2000s restoration, a light and music fountain was installed on Horseshoe Island in the Middle Tsaritsyno Pond. It is one of the biggest fountains of that type in Moscow.[9]

Architectural features of the Grand Palais

[edit]The basis of Bazhenov's architectural plan is formed by two equal wings, square in plan, intended for the apartments of Catherine II (right-wing) and Crown-prince Paul (left-wing).

The palace, despite its vivid neo-Gothic features (towers, lancet arches) in its solution is close to the canons of Classicism: strict symmetry, the tripartite division of the facades, the overall calm and balanced proportions, the monumental details (semi-columns in the corners of towers, fascias, loggias of side-wings). The hipped ends of the towers bear features tracing back to the towers of the Moscow Kremlin. In many respects, the Great Palace shows a different approach to the task of building a country residence "in the Gothic style".[10]

The palace was not completed due to the sudden death of Catherine II. By 1796 it already had a temporary roof painted black. This gave the building a gloomy appearance which affected the perception of contemporaries of the construction. It was only by the middle of the 19th century that critics started to give credit for the palace's architectural features.[10]

The ruined palace, which had not been used in any way during its history, was converted into a museum complex in 2005-2007.

Gallery

[edit]-

Palace lawn

-

Ponds

-

Bazhenov's "Opera House", 1776–1778

-

Smaller hall inside the grand palace

-

Palace front

-

Map of park locations in Tsaritsino

References

[edit]- ^ "Tsaritsyno Palace | Zamoskvorechie, Moscow | Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ "Tsaritsyno Palace | Zamoskvorechie, Moscow | Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Разгонов, Сергей Н. (1985). Василий Иванович Баженов (in Russian). М.: Искусство.

- ^ "Life in the Tsaritsyno Dachas in the XIX century".

- ^ "Tsatitsyno: historical restoration of "glamour DisneyLand"?".

- ^ Егорычев, Виктор (2008). Золотое Царицыно. Архитектурные памятники и ландшафты музея-заповедника «Царицыно» (in Russian). М.: Трэвел-Дизайн/ГМЗ «Царицыно».

- ^ "Царицынские курганы". Музей-заповедник «Царицыно» (in Russian). Retrieved 2022-06-27.

- ^ "Департамент градостроительства города Москвы". 2008-12-11. Archived from the original on 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ^ admin (2022-04-06). "Tsaritsyno Museum-Reserve * All PYRENEES · France, Spain, Andorra". All PYRENEES · France, Spain, Andorra. Retrieved 2023-05-04.

- ^ a b T︠S︡arit︠s︡yno : attrakt︠s︡ion s istorieĭ. Natalʹi︠a︡ Samutina, B. E. Stepanov, Наталья Самутина, Б. Е. Степанов. Moskva. 2014. ISBN 978-5-4448-0171-0. OCLC 889406090.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link)

External links and references

[edit]- Official website (in English and Russian)

- Photo of Palace Complex and Park

- Reviews on TripAdvisor (in English and Russian)

- Tsaritsyno Park - One of the Best Museums in Moscow (in English)

- Parks and gardens in Moscow

- Museums in Moscow

- Palaces in Moscow

- Royal residences in Russia

- Vasili Bazhenov buildings

- Gothic Revival architecture in Russia

- Art museums and galleries in Moscow

- Folk art museums and galleries

- Decorative arts museums in Russia

- Cultural heritage monuments of federal significance in Moscow