Tropico, California

Tropico, California | |

|---|---|

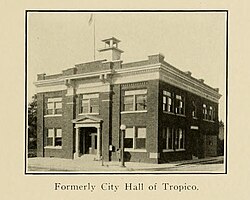

"Tropico City Hall" building, photographed c. 1922 (History of Glendale and vicinity via Library of Congress Digital) | |

| |

| Coordinates: 34°07′43″N 118°15′18″W / 34.1287°N 118.2549°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Los Angeles County |

Tropico is an archaic place name in Los Angeles County, California, United States, located in what is now south Glendale, California. Tropico was established in 1887 as a Southern Pacific railroad siding, was briefly an independent city in the 1910s, and was merged into Glendale in 1918.

History

[edit]The settlement was established on a dairy cattle ranch known as Rancho Santa Eulalia that was owned by W. C. B. Richardson.[1][2] Richardson bought the ranch from one Samuel M. Heath in 1868.[3]

Tropico was the first Southern Pacific railroad depot north of Los Angeles proper, located about 6 miles (9.7 km) north of the city.[4][5] The Los Angeles Times called the name Tropico "a horrible rumor...materialized into a fact."[6] The San Pedro and Salt Lake and/or "Glendale narrow-gauge" railroads also ran past Tropico.[5][7] The townsite was laid out in 1887 and bounded by what became Lexington, Colorado, Central, and Chevy Chase Drive.[8] Other Southern Pacific-adjacent towns (or railway sidings) established in the Los Angeles area in 1887 were Fillmore, Saugus, Bardsdale, Fernando, Pacoima, Tuni, Dundee, Burbank, Aurant, Ramona, Shorb's, Nadeau, The Palms, Almond, and Sansevain.[9] The station was built on a 13-acre (5.3 ha) lot donated by Richardson.[6] The depot was located at what is now Cerritos Avenue and San Fernando Road.[8] A newspaper writer described the Southern Pacific route from Los Angeles in 1891:[10]

Leaving Los Angeles by the Southern Pacific, the train soon crosses the Los Angeles river and winds along the east banks, through the comparatively narrow gorge which gives the river ingress from the north. On each side are rolling hills, above and beyond which, on the east, are the Sierras. Corn fields, vineyards and groves of eucalyptus trees dot the lower foothills. The first place reached is Tropico Station, six miles north of Los Angeles. The principal part of the settlement is 100 feet above and a mile from the station. It will be found described elsewhere in this issue, as also Glendale.[10]

By 1890, a number of market-garden farms in the area were worked by Chinese immigrants.[5] Japanese agricultural workers came to Tropico to work at the strawberry farms beginning in 1899.[11] Underground water from the Verdugo watershed was drawn for homes and farms by wells and windmills.[5] The settlement had a post office in 1900[2] and about 700 residents in 1903.[8] In 1903 the Los Angeles, Tropico and Glendale Electric Railroad Company made plans for an electric railway line "extending from the Los Angeles River south of Griffith Park to the Tropico schoolhouse, a distance of over a mile. This takes the line through Tropico across the Southern Pacific Railroad just south of the depot grounds, and thence north about midway between the Southern Pacific and the Glendale branch of the Salt Lake road."[12] The electric interurban line was completed in 1904.[3] In 1907 it took 20 minutes on the trolley to get from downtown Los Angeles to Tropico.[7] This line, which eventually became the Pacific Electric Railway's Glendale–Burbank Line, was initially dubbed the "strawberry line" after the area's leading crop.[13]

In 1910, the Los Angeles Times delivered a report from town boosters that, "Tropico stands at the gateway between the valley and the city. At this point are many signs of a new and substantial impetus. The Baumeister-Salyer piano factory is being built a little north of the center of town, G. H. A. Goodwin is opening a large subdivision, the Tropico Art Tile Works are being enlarged and the old Richardson ranch, where strawberries have been raised for years is about to be transformed Into a fine residence district, with cement walks and curbs, oiled streets and $4,000 to $5,000 houses and bungalows. A bank is one of the proposed features for the center of town and new business blocks will soon be erected."[14]

Tropico was an incorporated sixth-class[16] city of 861 acres (348 ha) beginning on March 15, 1911.[17][8] Tropico City Hall was completed in 1914 and housed the city government offices, a library, and the fire house.[16] Tropico ceased to exist as a municipality on January 9, 1918, when it was formally annexed to neighboring Glendale, California.[8][17] Tropico became one of the southern neighborhoods of Glendale,[18] described as the "heart of the industrial district" circa 1930.[19] In 1939, the Tropico district threatened to secede from Glendale and seek annexation by Los Angeles if requests for community improvements were not addressed.[20] The old city hall building, located at the intersection of Brand and Los Feliz, was demolished in 1940.[21]

Tropico was known for its strawberry production.[17][4] Pacific Art Tile Works (also known as Tropico Art Tile Works) and the Los Angeles Basket Factory were also based in the district.[4][22][16] Edward Weston opened a photography studio in Tropico in 1911.[23] There are a number of surviving Weston photographs of Tropico.[24][25]

A Tropico Bridge was built across the Los Angeles River in 1924.[26] The Tropico branch of the Glendale Public Library stood at 1501 S. Brand Blvd.[8] The name also survived for a time in a plant nursery, motel, and a convalescent hospital.[8] Tropico Avenue, an east–west thoroughfare, later became Los Feliz Blvd.[8] There is still a U.S. post office in Glendale called Tropico.[4]

Additional images

[edit]-

1887 application for a U.S. post office at Tropico (U.S. National Archives)

-

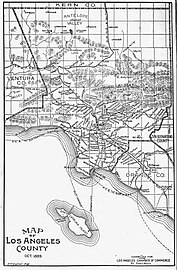

Tropico on a map of Los Angeles County published October 1893 for the World's Columbian Exposition

-

Cover of 1903 guide to Tropico (Online Archive of California)

-

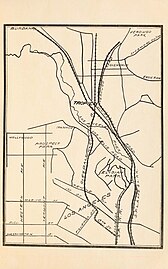

Tropico location map 1903

-

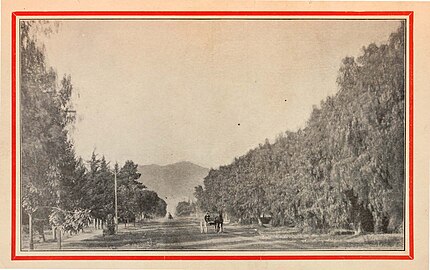

Road and orchard in Tropico 1903

-

"Tropico - Borthick's Subdivision" ad in Los Angeles Times 1906

-

Western Art Tile Works 1906

-

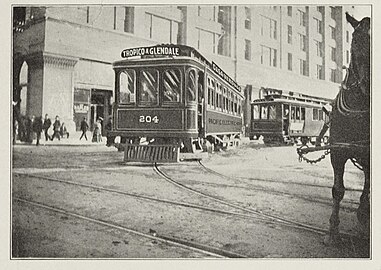

Pacific Electric train to Tropico & Glendale, and Casa Verdugo 1906

-

Tropico in foreground of 1916 road map "to Sunland, La Crescenta, and La Canada"

-

Corner of Glendale, Brand and Cypress with Glendale–Burbank Line streetcar 1910 (top) and in 1922 (bottom)

-

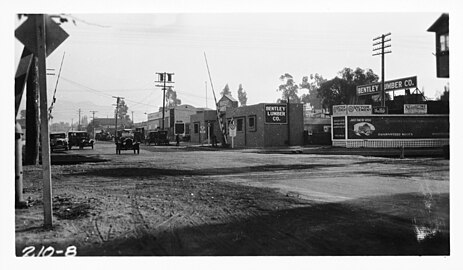

"S.P.Ry. grade crossing on Tropico Avenue, Glendale city limits, Los Angeles County, 1923" (AAA Archive via USC Digital Collections)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Memories of City of Tropico Flicker Anew". The Los Angeles Times. March 10, 1957. p. 217. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ a b "Tropico". The Los Angeles Times. January 1, 1900. p. 57. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ a b Sherer, John Calvin (1923). "VII: The Story of Tropico". History of Glendale and Vicinity. Glendale History Publishing Company. pp. 77–92.

- ^ a b c d Masters, Nathan (June 16, 2014). "The Lost City of Tropico, California". PBS SoCal. Retrieved 2023-09-26.

- ^ a b c d "In the San Fernando: The Big Valley, Its Towns and Tributaries". The Los Angeles Times. January 1, 1890. p. 46. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ a b "Glendale and Verdugo". The Los Angeles Times. May 28, 1887. p. 6. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ a b Guinn, James Miller (1907). A History of California and an Extended History of Its Southern Coast Counties: Also Containing Biographies of Well-known Citizens of the Past and Present. Historic Record Company. p. 395.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Snyder, Don (January 9, 1966). "Glendale's Lost City - Tropico: Only Name Remains". The Los Angeles Times. p. 257. Retrieved 2023-09-26. & https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-los-angeles-times-tropico-once-flou/132480818/

- ^ "Industrial Progress". Los Angeles Herald. August 13, 1887. p. 9. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ a b "San Fernando Valley". The Los Angeles Times. September 5, 1891. p. 4. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ U.S. Immigration Commission (1907–1910) (1911). Immigrants in Industries (in Twenty-five Parts). U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 387–388.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Tropico: New Electric Route". The Los Angeles Times. August 28, 1903. p. 19. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ "40th Anniversary of Glendale Rail Lines Celebrated" (PDF). Pacific Electric Magazine. May 1944. p. 12 – via library.metro.net.

- ^ "Rapid Progress on Edge of Annexation". The Los Angeles Times. January 30, 1910. p. 85. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ Bengtson, John (June 23, 2023). "Los Angeles Railway". Chaplin-Keaton-Lloyd film locations (and more). Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ a b c "Tropico". The Los Angeles Times. January 1, 1915. p. 38. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ a b c Morrison, Patt (September 13, 2022). "Moneta, Tropico, Lordsburg — where did L.A.'s phantom towns vanish to?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2023-09-26.

- ^ "The Los Angeles Times 01 Jan 1925, page 184". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ "Town Names in Valley Recall Earliest Days". The Los Angeles Times. March 10, 1930. p. 13. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ "City Government Change Asked in Glendale Secession Threat". The Los Angeles Times. January 12, 1939. p. 7. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ "Wrecking the Old "Tropico" City Hall". San Fernando Valley Times. June 13, 1940. p. 27. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ "Tropico: Los Angeles County California". oac.cdlib.org. Retrieved 2023-09-26.

- ^ "Edward Weston - National Portrait Gallery". www.npg.org.uk. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ "[Storefronts at Tropico, California] (The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection)". The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ "[Tropico, California from above] (The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection)". The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- ^ "Suit Against City Asks Bridge Fee". The Los Angeles Times. October 27, 1931. p. 23. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

Further reading

[edit]- "Tropico, the Beautiful Link City". American Globe. November 1916. pp. 3–15 – via New York Public Library & Google Books.

- Brown, Evan Nicole (July 30, 2018). "Tropico Post Office". Atlas Obscura.

- "Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps from Tropico, Los Angeles County, California". Sanborn Map Company. October 1908. Retrieved 2023-09-27 – via Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.