Tree of Liberty (symbol)

The Tree of Liberty has been a symbol of freedom since the French Revolution. As a tree of life, it also symbolizes continuity, growth, strength and power. In the 19th century, it became one of the symbols of the French Republic, along with the Marianne and the sower. Since 1999, it has been featured on French one-euro and two-euro coins.

Planted, generally in the busiest, most visible spot in a locality, as signs of joy and symbols of emancipation, these plants were to grow with the new institutions.

Origins

[edit]The custom of planting trees as a sign of popular joy is immemorial. It is found among the Gauls and Romans alike. The precursor of these trees was the maypole, which was planted in many places to celebrate the arrival of spring.[1] In Paris, until the end of the Ancien régime, the clerics of the Basoche planted a rootless tree in the palace courtyard every year, providing the occasion for a celebrated celebration. The first person in France to plant a Tree of Liberty, even several years before the Revolution, was Count Camille d'Albon, in 1782, in the gardens of his Franconville home, as a tribute to William Tell.

Trees of liberty during the French Revolution

[edit]The first trees: 1789–1791

[edit]At the time of the Revolution, in imitation of what had been done in the United States following the War of Independence with the Liberty poles,[2] the custom was introduced in France of ceremoniously planting a young poplar tree in French communes. The example was set in 1790 by the parish priest of Saint-Gaudent, in the Vienne department, who had an oak tree transplanted from the nearby forest into the middle of his village square.

The impetus of 1792

[edit]The planting of Tree of Libertys multiplied in the spring and summer of 1792: France, at war with Austria, was seized by a patriotic impulse, and the defense of the homeland became synonymous with that of the conquests of the Revolution. The tree thus became a powerful symbol of the revolutionary ideal.[3]

The poplar was preferred to the oak, and in early 1792, Lille, Auxerre and other towns planted Tree of Libertys. A few months later, more than sixty thousand of these trees were erected in all the communes of France, according to Abbé Grégoire.[4] According to the Marquis de Villette, Paris had over two hundred. Louis XVI himself presided over the erection of one of these trees in the Tuileries gardens, but it was felled in Pluviôse year II "in hatred of the tyrant". At the time of the King's trial, which led to his conviction, Barère de Vieuzac went so far as to paraphrase Thomas Jefferson, declaring: "The tree of liberty could not grow if it were not watered with the blood of kings".[5]

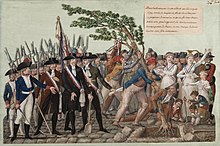

Inauguration

[edit]The planting of the Tree of Libertys was a very solemn affair, always accompanied by ceremonies and popular rejoicings in which all the authorities, magistrates, administrators and even the clergy, priests, constitutional bishops and even generals took part in the same patriotic enthusiasm. Adorned with flowers, tricolor ribbons, flags and cartouches with patriotic mottos, these trees served as stations, like altars of the fatherland, for processions and civic celebrations, along with many others.

Importance and care

[edit]

Tree of Libertys were considered public monuments. Maintained by the inhabitants with religious care, the slightest mutilation would have been considered a desecration. Inscriptions in verse and prose, couplets and patriotic stanzas attested to the local population's veneration for these revolutionary emblems. Special laws protected their consecration. A decree of the Convention ordered that the tree of liberty and the altar of the fatherland, overturned on March 27, 1793, in the department of Tarn, would be re-established at the expense of those who had destroyed them.

A large number of Tree of Libertys, uprooted in the midst of their growth, having dried up, the Convention ordered, by a decree of January 22, 1794, that "in all the communes of the Republic where the tree of liberty has perished, another will be planted by the 1st of Germinal". It entrusted this planting and its upkeep to the care of citizens, so that in each commune "the tree would flourish under the aegis of French liberty". The same law ordered that a tree be planted in the Tuileries Garden by the orphans of the defenders of the fatherland. Other decrees prescribed penalties for those who destroyed or mutilated the trees of liberty.

New trees were then planted, but despite all the surveillance they were subjected to, many were destroyed by counter-revolutionaries, who sawed them down or sprayed vitriol on their roots at night. These attacks were keenly felt by the people, who worshipped these plantations; the laws often punished them with the utmost severity, and death sentences were even handed down to the perpetrators. In Bédoin, Vaucluse, 63 people were executed, 500 houses razed to the ground for failing to report those guilty of uprooting such a tree,[7][8] and farmland sterilized with salt.[9] Three peasants from La Versanne who cut down a tree were guillotined in Lyon,[10] and a miller from Mas-Grenier was also guillotined in Toulouse for the same offence.[11] On the other hand, the revolutionary Marie Joseph Chalier planned to use a large ditch around the Tree of Liberty to smoke the blood of the guillotine victims on Pont Moraud in Lyon.[12]

These kinds of offenses were very common under the Thermidorian reaction. For example, on June 8, 1794, the patron saint's day in Hirsingue, some of the town's inhabitants cut down their tree. As a result, on the orders of Nicolas Hentz and Jean-Marie-Claude-Alexandre Goujon, representatives on mission to the Army of the Rhine, General Dièche ordered the arrest and detention in Besançon of all constitutional priests in the Rhine departments (Haut-Rhin, Bas-Rhin and Mont-Terrible) (they were released after Thermidor 9), and the destruction of the church.[13] On March 31, 1794, in Clermont, Michel Fauré was guillotined for uprooting a tree and shouting "Long live the King".[14] The Directoire saw to the replacement of those that had been knocked down, but Bonaparte soon ceased to maintain them, and even had some of those that had sprung up in various parts of Paris cut down. Under the Consulate, all these laws fell into disuse, and the Tree of Libertys that survived the Republican government lost their political character. But popular tradition preserved the memory of their origins.

Distribution outside France

[edit]

The soldiers of the Republic planted Tree of Libertys in every country they crossed. In a collection of Marceau's unpublished letters, published by Hippolyte Maze, the young republican general wrote to Jourdan on October 27, 1794: "that the tree of liberty was planted yesterday in Coblence in front of the Elector's palace". Similarly, during the French occupation of Switzerland, many trees were planted as a sign of allegiance to France, only to be uprooted when the country's armies left.

The mother country's example was followed even in the colonies, where they were even planted at slave markets. Napoleon Bonaparte went so far as to plant one in Milan, although the reaction of the population was more mixed, going so far as to uproot the tree and justify violent repression.[15]

Other trees were planted in the colonies (in Pondicherry) and in foreign countries: a Freedom Palm in Shanghai by Sun Yat-sen in 1912.[16]

The fate of Tree of Libertys in the 19th century

[edit]Felling during the Restoration

[edit]

When the Bourbons returned, there were still a large number of Tree of Libertys throughout France, which had been called Napoleon trees under the Empire.[17] Louis XVIII's government issued strict orders to uproot these last emblems of the Revolution. Most of these trees were cut down or uprooted under the Restoration, making them a rarity in towns and cities, although they could still be seen in rural communities.

Renewal

[edit]After the Three Glorious Years, a few communes still planted new Tree of Libertys, but enthusiasm soon waned, and few were planted. Not so after the February Revolution of 1848, when the practice was renewed. The provisional authorities did not fail to encourage the planting of Tree of Libertys, and the clergy was more than willing to bless them. One of Louis-Philippe I's former ministers even offered a sapling from his Paris park to plant outside his door, with the inscription: "Jeune, tu grandiras" ("Young, you'll grow").[18] Some towns, such as Bayeux, still have a tree of liberty in full vigor today.

A violent reaction led to the cutting down of almost all the Tree of Libertys in Paris at the beginning of 1850, by order of Police Prefect Carlier, and nearly caused bloodshed in the streets of the capital. However, in the opinion of a Legitimist newspaper, "the Tree of Libertys caused very little inconvenience to passers-by, and we fail to see how the men of order could be upset by these symbols. A tree offers a beautiful image of freedom without violence, and can in no way threaten ideas of social inequality, since in the development of a plant all branches are unequal precisely because they are free".[18]

The return of the Republic in 1870 was an opportunity to plant new trees. However, the context (the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, then the Paris Commune, and finally the conservative Republic) did not lend itself to this. Plantings were more frequent in 1889 (centenary of the storming of the Bastille), then in 1892 (centenary of the First French Republic). Other trees were planted in 1919–1920, to celebrate the victory of the right and the liberation of Alsace and Moselle, and others in 1944–1945, to mark the Liberation. Other anniversaries (1939, 1948, 1989) are celebrated on other occasions. A new tree is sometimes replanted when the old one dies.[16] As in the past, they sometimes receive a lukewarm reception.[19]

Other uses

[edit]Today, the Tree of Liberty appears in a highly stylized form, but as the main motif on French €1 and €2 coins, and on the logo of the French political party, the UMP.

Design for French €1 and €2 coins

[edit]The Tree of Liberty, also known as the Starry Tree design, is the obverse of the €1 and €2 coins, created by Joaquin Jimenez in 1999. The tree, whose branches, roots and trunk (encircled by the initials R and F) radiate out from a hexagon representing the French territory, is framed by the motto Liberté, égalité, fraternité written in all caps; the whole is surrounded by a circle of twelve stars.

According to its author, this new tree of liberty symbolizes a France whose roots and branches, turned towards the stars of Europe, tell its story and bear witness to its openness and growth. For the author, this new tree of liberty is the ideal subject to illustrate the French motto, as Victor Hugo made clear in his speech on March 2, 1848, a century and a half before the design was created.

UMP political party logo

[edit]The tree of liberty adopted by the Union pour un mouvement populaire (UMP), a French political party of the center and right, thus appears on its logo. It is white between blue and red in the center of the logo, echoing the three colors of the French flag, and features an oak or apple tree, typical trees of the French terroir and "fetishes" of the French right.

The oak, the tree of freedom par excellence, symbolizes in European culture durability, virility, power, stability and unity. The day after his death, Charles de Gaulle was depicted as a felled oak in a front-page drawing by Jacques Faizant in Le Figaro (November 11, 1970). As for the apple tree, it was one of the symbols of Jacques Chirac's campaign for election to the presidency of the French Republic in 1995. The apple tree, along with the apple, represented the fruits of France.

Whatever the species of tree, the symbolism of the Tree of Liberty is based on the universal values and humanist principles of the French Republic.

For historian Bernard Richard, "it could be said that it has taken the place occupied on the RPR 'logo' by the cross of Lorraine, which some people find annoying, or the Phrygian bonnet, which already offended some Gaullist deputies".[20]

Quotes

[edit]"The tree of liberty must be revived from time to time by the blood of patriots and tyrants."

— Thomas Jefferson, Letter to W. S. Smith, Nov. 13, 1787.

"It is a beautiful and true symbol for liberty that a tree! Liberty has its roots in the heart of the people, like the tree in the heart of the earth; like the tree it raises and spreads its branches in the sky; like the tree, it grows unceasingly and covers generations with its shade. The first tree of freedom was planted, eighteen hundred years ago, by God himself on Golgotha. The first tree of liberty is this cross on which Jesus Christ offered himself as a sacrifice for the liberty, equality and fraternity of the human race."

— Victor Hugo, Speech at the planting of a Tree of Liberty on the Place des Vosges, March 2, 1848.

References

[edit]- ^ Fechner, Erik (1987). "L'arbre de la liberté: Objet, symbole, signe linguistique". Mots: Les Langages du Politique. 15 (1): 23–42.

- ^ Le Bas, Philippe. France, dictionnaire encyclopédique (in French). Firmin Didot. p. 284.

- ^ Petit (1989, p. 28)

- ^ See Histoire des arbres de la liberté, quoted by Petit, Robert (1989). Les Arbres de la liberté à Poitiers et dans la Vienne (in French). Éditions CLEF 89/Fédération des œuvres laïques. p. 25. ISBN 978-2-905061-20-1.

- ^ "Citations françaises".

- ^ "Arbre de la liberté" (PDF).

- ^ "Quelques éléments d'histoire pour comprendre Bédoin".

- ^ Sens-Meyé, André (2016). "L'affaire de Bedoin, un exemple de Terreur provinciale". Archives départementales de Vaucluse.

- ^ "Monument aux victimes de la Révolution, Bédoin, Vaucluse".

- ^ "Claude Javogues (1759–1796)".

- ^ "Arbres de la liberté en Haute-Garonne".

- ^ "Crommelin family".

- ^ Le Clere, A. (1875). Histoire de l'Eglise catholique en France: d'après les documents les plus authentiques, depuis son origine jusqu'au concordat de Pie VII (in French). p. 174.

- ^ Sabatié, Amans-Claude (1914). Les tribunaux révolutionnaires en province (in French). P. Lethielleux.

- ^ Album littéraire et musical de la Minerve. 1848.

- ^ a b Petit (1989, pp. 187–188)

- ^ Ceccarelli, Albert (1989). La Révolution à l'Isle sur la Sorgue et en Vaucluse (in French). Éditions Scriba. p. 117. ISBN 978-2-86736-018-3.

- ^ a b Duckett (1853, p. 745)

- ^ Veniant, Jean (2012). "Le sapin de la liberté victime de vandales". Le Journal de Saône-et-Loire.

- ^ Richard (2011)

Bibliography

[edit]- Boursin, Elphège; Challamel, Augustin (1982). Dictionnaire de la révolution française (in French). Jouvet et Cie.

- Duckett, William (1853). Dictionnaire de la conversation et de la lecture (in French) (2nd ed.). Michel Lévy.

- Richard, Bernard (2011). Les Emblèmes de la République (in French). CNRS Éditions. ISBN 978-2-271-07299-3.