Treaty of Vienna (1731)

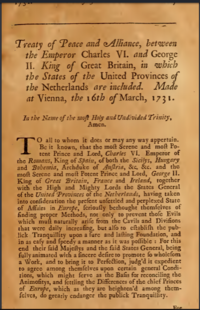

| Treaty of Peace and Alliance | |

|---|---|

| |

| Context | Britain and the Dutch Republic accept the Pragmatic Sanction; Austria withdraws from Parma & Piacenza and accepts Charles of Spain as duke; Closure of Ostend Company |

| Signed | 16 March 1731 |

| Location | Vienna |

| Negotiators | |

| Parties | |

The 1731 Treaty of Vienna was signed on 16 March 1731 between Great Britain and Emperor Charles VI on behalf of the Habsburg monarchy, with the Dutch Republic included as a party.

This marked the end of the Anglo-French Alliance that dominated Europe since the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, replacing it with the Anglo-Austrian Alliance. After Spain signed on 22 July 1731, Austria recognised Charles of Spain as Duke of Parma and Piacenza.

Background

[edit]

The period after the 1713 Peace of Utrecht was one of constant re-alignment among the European Powers as they attempted to solve issues without war. France in particular needed peace to rebuild its exhausted economy after the War of the Spanish Succession, which resulted in the 1716 Anglo-French Alliance. Although both sides were suspicious of each other, the succession of George I in 1714 and his concern for Hanover made the alliance more important to Britain than was previously the case.[1]

Utrecht confirmed Philip V as the first Bourbon king of Spain but left Britain in possession of the Spanish ports of Gibraltar and Mahón, Menorca, captured during the war. Regaining these was a priority for the new regime.[2] Spain also ceded their Italian possessions of Naples, Sicily, Milan and Sardinia. These became a focus for Spanish foreign policy largely due to Elisabeth Farnese, Philip's second wife. When they married in 1714, he already had two sons and she wanted to create an Italian inheritance for her own children.[3]

Commercial issues included the Austrian-owned Ostend Company, which competed for the East Indies trade with British, French and Dutch merchants, as well as Spanish concerns over British incursions in New Spain. As the 1730s began, Emperor Charles VI of Austria needed support for the 1713 Pragmatic Sanction and ensure the succession of his daughter Maria Theresa.[4]

The result was an almost continuous series of conferences and agreements, among them the 1725 Peace of Vienna between Austria and Spain. This alignment was short-lived, Charles VI deciding Austria's interests were better served by an alliance with Britain and the Dutch Republic.[5]

Details

[edit]

In the 1720 Treaty of The Hague, Britain, France, the Dutch Republic and Austria recognised Charles of Spain, third son of Philip V, as Duke of Parma and Tuscany.[6] Although reconfirmed by Britain and France in the 1729 Treaty of Seville, Austria refused to comply and occupied the Duchy when Antonio Farnese died in January 1731. The Treaty agreed to withdraw these and Charles of Spain was installed as Duke.[7]

The Austrian-backed Ostend East India Company was also closed; established in 1722, this had become a major competitor to the British and Dutch East India companies. Emperor Charles VI revoked the Company's charter in 1727 to ensure acceptance of the Pragmatic Sanction but Britain made its permanent closure a condition of signing the Treaty.[8]

Aftermath

[edit]During the 1733 to 1735 War of the Polish Succession, Charles of Spain seized the former Spanish possession of the Kingdom of Naples. As a result, the 1738 Treaty of Vienna returned Parma and Piacenza to Emperor Charles VI, until his death in 1740 led to the War of the Austrian Succession.[9] The 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle transferred Parma to Charles of Spain's younger brother Philip; Charles succeeded his elder brother Ferdinand VI as king of Spain in 1759.[10]

The Anglo-Austrian alliance lasted until the 1756 Diplomatic Revolution led to a realignment of relationships; the most significant was long-time rivals France and Austria becoming allies.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ Lindsay 1957, p. 202.

- ^ Tucker 2012, p. 122.

- ^ Solano 2011, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Lindsay 1957, pp. 201.

- ^ Savelle 1974, p. 124.

- ^ Lessafer, Randall. "The 18th-century Antecedents of the Concert of Europe II: The Quadruple Alliance of 1718". Oxford Public International Law. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ Savelle 1974, p. 126.

- ^ Butel 1997, p. 198.

- ^ Anderson 1995, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Lindsay 1957, pp. 200.

- ^ Lindsay 1957, pp. 449–450.

Sources

[edit]- Anderson, MS (1995). The War of the Austrian Succession 1740–1748. Routledge. ISBN 978-0582059504.

- Butel, Paul (1997). Européens et espaces maritimes: vers 1690-vers 1790. Par cours universitaires. Bordeaux University Press.

- Lindsay, JO (1957). International Relations in The New Cambridge Modern History: Volume 7, The Old Regime, 1713–1763. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521045452.

- Savelle, Max (1974). Empires to Nations: Expansion in America, 1713-1824 (Europe and the World in Age of Expansion). University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0816607815.

- Solano, Ana Crespa (2011). "A Change of Ideology in Imperial Spain?". In Rommelse, Gijs; Onnekink, David (eds.). Ideology and Foreign Policy in Early Modern Europe (1650–1750). Routledge. ISBN 978-1409419136.

- Tucker, Spencer C, ed. (2012). Almanac of American Military History; Volume I. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1598845303.

External links

[edit]- Lessafer, Randall. "The 18th-century Antecedents of the Concert of Europe II: The Quadruple Alliance of 1718". Oxford Public International Law. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- 1731 treaties

- 1731 in Great Britain

- 1731 in the Habsburg monarchy

- 1731 in Spain

- 18th century in Vienna

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Great Britain

- Treaties of the Habsburg monarchy

- Treaties of the Holy Roman Empire

- Peace treaties of the Dutch Republic

- Treaties of the Spanish Empire

- Great Britain–Habsburg monarchy relations

- Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor

- Charles III of Spain