Tongues Untied

| Tongues Untied | |

|---|---|

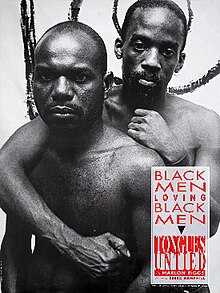

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Marlon T. Riggs |

| Produced by | Marlon T. Riggs |

| Starring |

|

| Narrated by |

|

| Distributed by | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 55 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Tongues Untied is a 1989 American video essay[1][2] experimental documentary film directed by Marlon T. Riggs,[3] and featuring Riggs, Essex Hemphill, Brian Freeman. and more.[4] The film seeks, in its author's words to, "...shatter the nation's brutalizing silence on matters of sexual and racial difference."

In 2022, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[5]

Content

[edit]The film blends documentary footage with personal account and poetry in an attempt to depict the specificity of Black gay identity. The "silence" referred to throughout the film is that of Black gay men, who are unable to express themselves because of the prejudices of white and Black heterosexual society, as well as the white gay society.

Riggs brings awareness to the issues Black gay men face.[6] They are excluded from gay communities because these communities are white-centered and fail to understand the intersecting identities of race and sexuality. Riggs experienced this in San Francisco, California within the Castro District, in which he states, "I was immersed in vanilla" and witnessed the absence of the Black gay image.[7]

In addition, Riggs gives examples of media in which black men are hypersexualized for white sexual pleasure and racistly portrayed Black individuals. Black gay men are placed in a divide because their voices are excluded from these LGBTQIA+ communities, but their bodies are sexualized for white viewing pleasure.[7]

Furthermore, Black men are supposed to represent hyper-masculinity, and when Black gay men associate with homosexuality, they are seen as being weak.[8] With their gay identity, however, a Black man is expected to be both hyper-feminine and hyper-masculine.[7] These are the stereotypes and stigmas that oppress Black gay men.[8]

Within their Black communities, black homophobia is also present.[7] Riggs displays footage of church leaders preaching that gay relationships are an abomination and Black political activists who consider being Black and gay to be a conflict of loyalties.[6]

The narrative structure of Tongues Untied is both non-linear and unconventional. Besides including documentary footage detailing North American Black gay culture, Riggs also tells of his own experiences as a gay man. These include the realization of his sexual identity and of coping with the deaths of many of his friends to AIDS. Other elements within the film include footage of the Civil Rights Movement and clips of Eddie Murphy performing a homophobic stand-up routine.

The documentary dealt with the simultaneous critique of the politics of racism, homophobia and exclusion as they are intertwined with contemporary sexual politics. The film is a part of a body of films and videos which examine central issues in the lives of lesbian and gay Black people. Riggs' work challenged documentary film's generic boundaries of conformity at that time.

Release and reception

[edit]At the time of its release, the film was considered controversial because of its frank portrayal of two men kissing. Presidential candidate Pat Buchanan cited Tongues Untied as an example of how President George H. W. Bush was using taxpayer's money to fund "pornographic art". In his defense, Riggs stated that, "Implicit in the much overworked rhetoric of community standards is the assumption of only one central community (patriarchal, heterosexual and usually white) and only one overarching cultural standard ditto."

Controversy over broadcast

[edit]When Tongues Untied was scheduled to be aired on the POV television series on PBS (and even before it was broadcast), it triggered a national controversy. Along with his own funds, Riggs had financed the documentary with a $5,000 grant from the Western States Regional Arts Fund, a re-granting agency funded by the National Endowment for the Arts, an independent federal agency that provides funding and support for visual, literary, and performing artists. POV also received funding from the National Endowment for the Arts in the amount of $250,000.[9][10]

News of the film's impending airing sparked a national debate about whether or not it is appropriate for the federal government of the United States to fund artistic creations that offended some.[10]

Reverend Donald E. Wildmon, the president of the American Family Association, attacked PBS and the National Endowment for the Arts for airing Tongues Untied but hoped that the film would be widely seen, because he believed most Americans would find it offensive. "This will be the first time millions of Americans will have an opportunity to see the kinds of things their tax money is being spent on," he said. "This is the first time there is no third party telling them what is going on; they can see for themselves."

Riggs defended the film, saying it was meant to "shatter this nation's brutalizing silence on matters of sexual and racial difference."[11] He observed that the widespread attack on PBS and the National Endowment for the Arts in response to the film was predictable, since "any public institution caught deviating from their puritanical morality is inexorably blasted as contributing to the nation's social decay."[12]

Riggs said, "implicit in the much overworked rhetoric about 'community standards' is the assumption of only one central community (patriarchal, heterosexual and usually white) and only one overarching cultural standard to which television programming must necessarily appeal." Riggs stated that ironically, the censorship campaign against Tongues Untied actually brought more publicity to the film than it would have otherwise received and thus enhanced its effectiveness in challenging societal standards regarding depictions of race and sexuality.[12]

Marc Weiss, executive producer of POV, and Jennifer Lawson, Vice President for Programming at PBS, vigorously defended the broadcast[13][14] and, although some public TV stations did not air the film, many stations did, saying it should be available for people who wanted to see it.

The broadcast of the film was criticized by several conservative US Senators, who vehemently objected to using taxpayer money to fund what they believed was pornography.[15]

At the same time, the national broadcast of Tongues Untied was applauded by many others who resoundingly defended the work, among them Norman Lear's People for the American Way.

In the 1992 Republican presidential primaries, presidential candidate Pat Buchanan cited Tongues Untied as an example of how President George H. W. Bush was investing "our tax dollars in pornographic and blasphemous art." Buchanan released an anti-Bush television advertisement for his campaign using re-edited clips from Tongues Untied[15] that violated U.S. Copyright law. The ad was quickly removed from television channels after Riggs successfully demonstrated Buchanan's copyright infringement.

Legacy

[edit]The year 2019 marked the 30th anniversary of the release of Tongues Untied and 25 years since Riggs' death. What began as an idea formulated by Signifyin' Works President Vivian Kleiman, eventually garnered support from the Ford Foundation, and Signifyin' Works seeded international events to introduce the work to a new generation. A nine-day retrospective curated by Ashley Clark was launched at the Brooklyn Academy of Music and was entitled Race, Sex & Cinema: The World of Marlon Riggs.[16] Discussions and panels were led by the likes of Raquel Gates, Yance Ford, Vivian Kleiman, Steven Thrasher, Katherine Cheairs, Herman Gray, and Steven G. Fullwood.[17][18]

In May, 2019, the Peabody Awards honored Marlon and Tongues Untied with a tribute, which Billy Porter of the award-winning FX series Pose presented. In conversation before the event with Vivian Kleiman, he noted that he saw Tongues Untied when it was broadcast on PBS, and the film changed his life, and gave him his voice at an early age.[19]

To celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Teddy Awards, the film was selected to be shown at the 66th Berlin International Film Festival in February 2016.[20]

New York Times critic-at-large Wesley Morris wrote "Tongues Untied is Riggs's unclassifiable scrapbook of black gay male sensibility (a hallucinatory whir of style, memory, psychology).... This is storytelling that arises from joy and pain and pride (Riggs's clearest emotional forebear is James Baldwin)."[21]

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a score of 100% based on 12 reviews, with an average rating of 6.4/10.[22]

In 2022, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Brief Descriptions and Expanded Essays of Titles at National Film Registry

- ^ No Regrets: A Celebration of Marlon Briggs|BAMPFA

- ^ Queer & Now & Then: 1991 - Film Comment

- ^ Bell, Chris (2006). "American AIDS Film". In Gerstner, David A. (ed.). Routledge International Encyclopedia of Queer Culture (1 ed.). Routledge. pp. 28–29. ISBN 9780415306515. Retrieved 2022-06-15.

- ^ a b Ulaby, Neda (December 14, 2022). "'Iron Man,' 'Super Fly' and 'Carrie' are inducted into the National Film Registry". NPR. Retrieved December 14, 2022.

- ^ a b "Tongues Untied". Senses of Cinema. 2000. Retrieved February 11, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Tongues Untied: Giving a Voice to Black Gay Men". Kanopy.com. Retrieved February 11, 2019.

- ^ a b Fields, Errol (2016). "The Intersection of Sociocultural Factors and Health-Related Behavior in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth: Experiences Among Young Black Gay Males as an Example". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 63 (6): 1091–1106. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.009. PMC 5127594. PMID 27865335.

- ^ Deane, Pamela S. "Riggs, Marlon: U.S. Filmmaker." The Museum of Broadcast Communications. MBC, 2011. 27 January 2011. Web.

- ^ a b Prial, Frank J. (June 25, 1991). "TV Film About Gay Black Men Is Under Attack". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ The Criterion Collection

- ^ a b Riggs, Marlon (1996). "Tongues Re-Tied". In Renov, Michael; Suderburg, Erika (eds.). Resolutions: Contemporary Video Practices. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 185–188. ISBN 978-0-8166-2330-3.

- ^ "Tongues Tied". Village Voice. July 2, 1991. Retrieved 2019-05-11 – via www.robertatkins.net.

- ^ Bullert, B. J. (1997). Public Television: Politics and the Battle Over Documentary Film. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813524702.

- ^ a b "On the Urge to Purge Public TV". Los Angeles Times. 1992-03-06. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ "Race, Sex & Cinema: The World of Marlon Riggs". BAM.org. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Alm, David (February 5, 2019). "Marlon Riggs, Icon of Queer and Black Cinema, Celebrated in Brooklyn". Forbes.

- ^ Als, Hilston. "Marlon Riggs Retrospective". The New Yorker.

- ^ "Tongues Untied tribute". Peabody Awards. 19 May 2019.

- ^ "Berlinale 2016: Panorama Celebrates Teddy Award's 30th Anniversary and Announces First Titles in Programme". Berlinale. Archived from the original on 21 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ Morris, Wesley (6 February 2019). "Blackness, Gayness, Representation: Marlon Riggs Unpacks It All in His Films". The New York Times.

- ^ "Tongues Untied - The Black Gay Male Experience". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved June 14, 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Diawara, Manthia (1993). Black American Cinema. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415903974.

- Gerstner, David (2011). Queer Pollen: White Seduction, Black Male Homosexuality, and the Cinematic. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. pp. 138–213. ISBN 978-0-252-07787-6.

- Mercer, Kobena (1994). "Skin Head Sex Thing: Racial Difference and the Homoerotic Imaginary". Welcome to the Jungle: New Positions in Black Cultural Studies (1st ed.). Psychology Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0415906357.

External links

[edit]- 1989 films

- POV (TV series) films

- 1989 LGBTQ-related films

- 1989 independent films

- Documentary films about African Americans

- Documentary films about HIV/AIDS

- American independent films

- African-American LGBTQ-related films

- African-American films

- Films directed by Marlon Riggs

- 1980s English-language films

- HIV/AIDS in American films

- 1980s American films

- United States National Film Registry films

- American LGBTQ-related documentary films

- Essays about culture

- English-language documentary films

- English-language independent films