The Great Dictator

| The Great Dictator | |

|---|---|

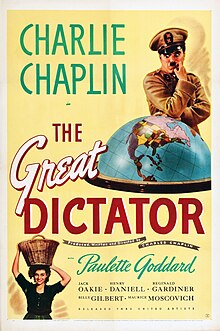

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Charlie Chaplin |

| Written by | Charlie Chaplin |

| Produced by | Charlie Chaplin |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 125 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.2 million[2] |

| Box office | $5 million (worldwide rentals)[3] |

The Great Dictator is a 1940 American anti-fascist, political satire, and black comedy film written, directed, and produced by, and starring, British filmmaker Charlie Chaplin. Having been the only Hollywood filmmaker to continue to make silent films well into the period of sound films, Chaplin made this his first true sound film.

Chaplin's film advanced a stirring condemnation of the German and Italian dictators Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, as well as fascism, antisemitism, and the Nazis. At the time of its first release, the United States was still at peace with Nazi Germany and neutral during what were the early days of World War II. Chaplin plays both leading roles: a ruthless fascist dictator and a persecuted Jewish barber.

The Great Dictator was popular with audiences, becoming Chaplin's most commercially successful film.[4] Modern critics have praised it as a historically significant film, one of the greatest comedy films ever made and an important work of satire. In 1997, it was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[5][6] The Great Dictator was nominated for five Academy Awards – Outstanding Production, Best Actor, Best Writing (Original Screenplay), Best Supporting Actor for Jack Oakie, and Best Music (Original Score).

In his 1964 autobiography, Chaplin stated that he could not have made the film if he had known about the true extent of the horrors of the Nazi concentration camps at that time.[7]

Plot

[edit]On the Western Front in 1918, a Jewish soldier fighting for the Central Powers nation of Tomainia[8] valiantly saves the life of a wounded pilot, Commander Schultz, who carries valuable documents that could secure a Tomainian victory. However, after running out of fuel, their plane crashes into a tree and the soldier subsequently suffers memory loss. Upon being rescued, Schultz is informed that Tomainia has officially surrendered to the Allied Forces, while the Jewish soldier is carried off to a hospital.

Twenty years later, still suffering from amnesia, the Jewish soldier returns to his previous profession as a barber in a ghetto. The ghetto is now governed by Schultz who has been promoted in the Tomainian regime, now transformed into a dictatorship under the ruthless Adenoid Hynkel.

The barber falls in love with a neighbor, Hannah, and together they try to resist persecution by military forces. The stormtroopers capture the barber and are about to kill him, but Schultz recognizes him and restrains them. By recognizing him, and reminding him of World War I, Schultz helps the barber regain his memory.

Meanwhile, Hynkel tries to finance his ever-growing military forces by borrowing money from a Jewish banker called Hermann Epstein, leading to a temporary ease on the restrictions on the ghetto. However, ultimately the banker refuses to lend him the money. Furious, Hynkel orders a purge of the Jews. Schultz protests against this inhumane policy and is sent to a concentration camp. He escapes and hides in the ghetto with the barber. Schultz tries to persuade the Jewish family to assassinate Hynkel in a suicide attack, but they are dissuaded by Hannah. Troops search the ghetto, arrest Schultz and the barber, and send both to a concentration camp. Hannah and her family flee to freedom at a vineyard in the neighboring country of Osterlich.

Hynkel has a dispute with the dictator of the nation of Bacteria, Benzino Napaloni, over which country should invade Osterlich. The two dictators argue over a treaty to govern the invasion, while dining together at an elaborate buffet, which happens to provide a jar of English mustard. The quarrel becomes heated and descends into a food fight, which is only resolved when both men eat the hot mustard and are shocked into cooperating. After signing the treaty with Napaloni, Hynkel orders the invasion of Osterlich. Hannah and her family are trapped by the invading force and beaten by a squad of arriving soldiers.

Escaping from the camp in stolen uniforms, Schultz and the barber, dressed as Hynkel, arrive at the Osterlich frontier, where a victory parade crowd is waiting to be addressed by Hynkel. The real Hynkel is mistaken for the barber while out duck hunting in civilian clothes and is knocked out and taken to the camp. Schultz tells the barber to go to the platform and impersonate Hynkel, as the only way to save their lives once they reach Osterlich's capital. The barber has no other choice. He announces that he (as Hynkel) has had a change of heart and makes an impassioned speech for brotherhood and goodwill, encouraging soldiers to fight for liberty, and unite the people in the name of democracy.

He then addresses a message of hope to Hannah: "Look up, Hannah. The soul of man has been given wings, and at last he is beginning to fly. He is flying into the rainbow, into the light of hope, into the future, the glorious future that belongs to you, to me, and to all of us." Hannah hears the barber's voice on the radio. She turns toward the rising sunlight, and says to her fellows: "Listen."

Cast

[edit]People of the ghetto

[edit]- Charlie Chaplin as a Jewish barber, a soldier during World War I who loses his memory for about 20 years. After having rescued Schultz during the war, he meets his friend again under radically changed circumstances.

- Paulette Goddard as Hannah, the barber's neighbor. She lives in the ghetto next to the barber shop. She supports the barber against the Tomainian stormtroopers.

- Maurice Moscovich as Mr. Jaeckel, an elderly Jew who befriends Hannah. Mr. Jaeckel is the renter of the barber salon.

- Emma Dunn as Mrs. Jaeckel

- Bernard Gorcey as Mr. Mann

- Paul Weigel as Mr. Agar

- Chester Conklin as the barber's customer

People of the palace

[edit]- Charlie Chaplin as Adenoid Hynkel, the dictator, or "Phooey",[9] of Tomainia (a parody of Adolf Hitler, the Führer of Nazi Germany)[10] who attacks the Jews with his stormtroopers. He has Schultz arrested and has his stormtroopers hunt down the Jewish barber. Hynkel is later arrested by his own soldiers in the woods near the border, who mistake him for the Jewish barber.

- Jack Oakie as Benzino Napaloni, the Diggaditchie of Bacteria (a parody of Benito Mussolini, Il Duce of Italy and a reference to French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte).[10]

- Reginald Gardiner as Commander Schultz, a Tomainian who fought in World War I, who commands soldiers in the 1930s. He has his troops abstain from attacking Jews, but is arrested by Hynkel, after which he becomes a loyal ally to the barber. He later leads the invasion of Osterlich and helps the barber pretend to be Adenoid Hynkel in his (successful) attempt at saving Osterlich.

- Henry Daniell as Garbitsch, a parody of Joseph Goebbels,[10] and Hynkel's loyal and stoic Secretary of the Interior and Minister of Propaganda.

- Billy Gilbert as Herring, a parody of Hermann Göring,[10] and Hynkel's Minister of War. He supervises demonstrations of newly developed weapons, which tend to fail and annoy Hynkel.

- Grace Hayle as Madame Napaloni, the wife of Benzino who later dances with Hynkel. In Italy, scenes involving her were all cut out of respect to Benito Mussolini's widow Rachele until 2002.

- Carter DeHaven as Spook, the Bacterian ambassador.

Other cast

[edit]- Stanley "Tiny" Sandford as a comrade soldier in 1918

- Joe Bordeaux as ghetto extra

- Hank Mann as stormtrooper stealing fruit

Also featuring Esther Michelson, Florence Wright, Eddie Gribbon, Robert O. Davis, Eddie Dunn, Nita Pike and Peter Lynn.

Production

[edit]According to Jürgen Trimborn's biography of Nazi propaganda filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, both Chaplin and French filmmaker René Clair viewed Riefenstahl's Triumph of the Will together at a showing at the New York Museum of Modern Art. Filmmaker Luis Buñuel reports that Clair was horrified by the power of the film, crying out that this should never be shown or the West was lost. Chaplin, on the other hand, laughed uproariously at the film. He used it to inspire many elements of The Great Dictator, and, by repeatedly viewing this film, Chaplin could closely mimic Hitler's mannerisms.[11]

Trimborn suggests that Chaplin decided to proceed with making The Great Dictator after viewing Riefenstahl's film.[12] Hynkel's rally speech near the beginning of the film, delivered in German-sounding gibberish, is a caricature of Hitler's oratory style, which Chaplin also studied carefully in newsreels.[13]

The film was directed by Chaplin (with his half-brother Wheeler Dryden as assistant director), and written and produced by Chaplin. The film was shot largely at the Charlie Chaplin Studios and other locations around Los Angeles.[14] The elaborate World War I scenes were filmed in Laurel Canyon. Chaplin and Meredith Willson composed the music. Filming began in September 1939 (coincidentally soon after Germany invaded Poland, triggering World War II) and finished six months later.

Chaplin wanted to address the escalating violence and repression of Jews by the Nazis throughout the late 1930s, the magnitude of which was conveyed to him personally by his European Jewish friends and fellow artists. Nazi Germany's repressive nature and militarist tendencies were well known at the time. Ernst Lubitsch's 1942 To Be or Not To Be dealt with similar themes, and also used a mistaken-identity Hitler figure. But Chaplin later said that he would not have made the film had he known of the true extent of the Nazis' crimes.[4] After the horror of the Holocaust became known, filmmakers struggled for nearly 20 years to find the right angle and tone to satirize the era.[15]

In the period when Hitler and his Nazi Party rose to prominence, Chaplin was becoming internationally popular. He was mobbed by fans on a 1931 trip to Berlin, which annoyed the Nazis. Resenting his style of comedy, they published a book titled The Jews Are Looking at You (1934), describing the comedian as "a disgusting Jewish acrobat" (although Chaplin was not Jewish). Ivor Montagu, a close friend of Chaplin's, relates that he sent the comedian a copy of the book and always believed that Chaplin decided to retaliate with making Dictator.[16]

In the 1930s, cartoonists and comedians often built on Hitler and Chaplin having similar mustaches. Chaplin also capitalized on this resemblance in order to give his Little Tramp character a "reprieve".[17]

In his memoir My Father, Charlie Chaplin, Chaplin's son Charles Chaplin Jr. described his father as being haunted by the similarities in background between him and Hitler; they were born four days apart in April 1889, and both had risen to their present heights from poverty. He wrote:

Their destinies were poles apart. One was to make millions weep, while the other was to set the whole world laughing. Dad could never think of Hitler without a shudder, half of horror, half of fascination. "Just think", he would say uneasily, "he's the madman, I'm the comic. But it could have been the other way around."[18]

Chaplin prepared the story throughout 1938 and 1939, and began filming in September 1939, six days after the beginning of World War II. He finished filming almost six months later. The 2002 TV documentary on the making of the film, The Tramp and the Dictator,[19] presented newly discovered footage of the film production (shot by Chaplin's elder half-brother Sydney) that showed Chaplin's initial attempts at the film's ending, filmed before the fall of France.[4]

According to The Tramp and the Dictator, Chaplin arranged to send the film to Hitler, and an eyewitness confirmed he saw it.[4] Hitler's architect and friend Albert Speer denied that the leader had ever seen it.[20] Hitler's response to the film is not recorded, but another account tells that he viewed the film twice.[21]

Some of the signs in the shop windows of the ghetto in the film are written in Esperanto, a language that Hitler condemned as an anti-nationalist Jewish plot to destroy German culture because it was an international language whose founder was a Polish Jew.[22]

Music

[edit]The film score was written and composed by Meredith Willson, later known as composer and librettist of the 1957 musical comedy The Music Man:

I've seen [Chaplin] take a soundtrack and cut it all up and paste it back together and come up with some of the dangdest effects you ever heard—effects a composer would never think of. Don't kid yourself about that one. He would have been great at anything—music, law, ballet dancing, or painting—house, sign, or portrait. I got the screen credit for The Great Dictator music score, but the best parts of it were all Chaplin's ideas, like using the Lohengrin "Prelude" in the famous balloon-dance scene.[23]

According to Willson, the scene in which Chaplin shaves a customer to Brahms' Hungarian Dance No. 5 had been filmed before he arrived, using a phonograph record for timing. Willson's task was to re-record it with the full studio orchestra, fitting the music to the action. They had planned to do it painstakingly, recording eight measures or less at a time, after running through the whole scene to get the overall idea. Chaplin decided to record the run-through in case anything was usable. Willson later wrote, "by dumb luck we had managed to catch every movement, and that was the first and only 'take' made of the scene, the one used in the finished picture".[23]

James L. Neibaur has noted that among the many parallels that Chaplin noted between his own life and Hitler's was an affinity for Wagner's music.[24] Chaplin's appreciation for Wagner has been noted in studies of the director's use of film music.[25] Many commentators have noted Chaplin's use of Wagner's Lohengrin prelude when Hynkel dances with the globe-balloon.[24][26][27] Chaplin repeated the use of the Lohengrin prelude near the conclusion when the exiled Hannah listens to the Jewish barber's speech celebrating democracy and freedom.[28] The music is interrupted during the dictator's dance but it is heard to climax and completion in the barber's pro-democracy speech.

Commenting on this, Lutz Peter Koepnick writes in 2002,

How can Wagner at once help emphasize a progressivist vision of human individualism and a fascist preview of absolute domination? How can the master's music simultaneously signify a desire for lost emotional integrity and for authoritative grandeur? Chaplin's dual use of Lohengrin points towards unsettling conjunctions of Nazi culture and Hollywood entertainment. Like Adorno, Chaplin understands Wagner as a signifier of both: the birth of fascism out of the spirit of the total work of art and the origin of mass culture out of the spirit of the most arduous aesthetic program of the 19th century. Unlike Adorno [who identifies American mass culture and fascist spectacle], Chaplin wants his audience to make crucial distinctions between competing Wagnerianisms. Both...rely on the driving force of utopian desires, on...the promise of self-transcendence and authentic collectivity, but they channel these mythic longings in fundamentally different directions. Although [Chaplin] exposes the puzzling modernity of Nazi politics, Chaplin is unwilling to write off either Wagner or industrial culture. [Chaplin suggests] Hollywood needs Wagner as never before in order to at once condemn the use of fantasy in fascism and warrant the utopian possibilities in industrial culture.[29]

Reception

[edit]

Chaplin's film was released nine months after Hollywood's first parody of Hitler, the short subject You Nazty Spy! by the Three Stooges, which premiered in January 1940.[30][self-published source?] Chaplin had been planning his feature-length work for years, and began filming in September 1939. Hitler had been previously allegorically pilloried in the 1933 German film The Testament of Dr. Mabuse, by Fritz Lang.[31]

The film was well received in the United States at the time of its release and was popular with the American public. For example, Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called the film "a truly superb accomplishment by a truly great artist" and "perhaps the most significant film ever produced."[32] The film was also popular in the United Kingdom, drawing 9 million to the cinemas,[33] despite Chaplin's fears that wartime audiences would dislike a comedy about a dictator. The film earned theater rentals of $3.5 million from the U.S. and Canada[34] and $5 million in total worldwide rentals.[3]

The film was banned in several Latin American countries, where there were active movements of Nazi sympathizers.[35]

During the film's production, the British government had announced that it would prohibit its exhibition in the United Kingdom, in keeping with its appeasement policy concerning Nazi Germany,[36] but by the time the film was released, the UK was at war with Germany and the film was welcomed in part for its obvious propaganda value. In 1941, London's Prince of Wales Theatre screened its UK premiere. The film had been banned in many parts of Europe, and the theatre's owner, Alfred Esdaile, was apparently fined for showing it.[37]

When the film was released in France in 1945, it became the most popular film of the year, with admissions of 8,280,553.[38] The film was voted at No. 24 on the list of "100 Greatest Films" by the prominent French magazine Cahiers du cinéma in 2008.[39] In 2010, The Guardian considered it the 22nd-best comedy film of all time.[40] The film was voted at No. 16 on the list of The 100 greatest comedies of all time by a poll of 253 film critics from 52 countries conducted by the BBC in 2017.[41]

Chaplin biographer Jeffrey Vance concludes his lengthy examination of the film, in his book Chaplin: Genius of the Cinema, by asserting the film's importance among the great film satires. Vance writes, "Chaplin's The Great Dictator survives as a masterful integration of comedy, politics and satire. It stands as Chaplin's most self-consciously political work and the cinema's first important satire."[42]

Vance further reports that a refugee from Germany who had worked in the film division of the Nazi Ministry of Culture before deciding to flee told Chaplin that Hitler had watched the movie twice, entirely alone both times. Chaplin replied that he would "... give anything to know what he thought of it."[43]

Chaplin's Tramp character and the Jewish barber

[edit]

There is no critical consensus on the relationship between Chaplin's earlier Tramp character and the film's Jewish barber, but the trend is to view the barber as a variation on the theme. French film director François Truffaut later noted that early in the production, Chaplin said he would not play The Tramp in a sound film.[44] Turner Classic Movies says that years later, Chaplin acknowledged a connection between The Tramp and the barber. Specifically, "There is some debate as to whether the unnamed Jewish barber is intended as the Tramp's final incarnation. Although in his autobiography he refers to the barber as the Little Tramp, Chaplin said in 1937 that he would not play the Little Tramp in his sound pictures."[45]

In My Autobiography, Chaplin would write, "Of course! As Hitler I could harangue the crowds all I wished. And as the tramp, I could remain more or less silent." The New York Times, in its original review (16 October 1940), specifically sees him as the tramp. However, in the majority of his so-called tramp films, he was not literally playing a tramp. In his review of the film years after its release, Roger Ebert says, "Chaplin was technically not playing the Tramp." He also writes, "He [Chaplin] put the Little Tramp and $1.5 million of his own money on the line to ridicule Hitler."[46]

Critics who view the barber as different include Stephen Weissman, whose book Chaplin: A Life speaks of Chaplin "abandoning traditional pantomime technique and his little tramp character".[47] DVD reviewer Mark Bourne asserts Chaplin's stated position: "Granted, the barber bears more than a passing resemblance to the Tramp, even affecting the familiar bowler hat and cane. But Chaplin was clear that the barber is not the Tramp and The Great Dictator is not a Tramp movie."[48] The Scarecrow Movie Guide also views the barber as different.[49]

Annette Insdorf, in her book Indelible Shadows: Film and the Holocaust (2003), writes that "There was something curiously appropriate about the little tramp impersonating the dictator, for by 1939 Hitler and Chaplin were perhaps the two most famous men in the world. The tyrant and the tramp reverse roles in The Great Dictator, permitting the eternal outsider to address the masses".[50] In The 50 Greatest Jewish Movies (1998), Kathryn Bernheimer writes, "What he chose to say in The Great Dictator, however, was just what one might expect from the Little Tramp. Film scholars have often noted that the Little Tramp resembles a Jewish stock figure, the ostracized outcast, an outsider."[51]

Several reviewers of the late 20th century describe the Little Tramp as developing into the Jewish barber. In Boom and Bust: American Cinema in the 1940s, Thomas Schatz writes of "Chaplin's Little Tramp transposed into a meek Jewish barber",[52] while, in Hollywood in Crisis: Cinema and American Society, 1929–1939, Colin Shindler writes, "The universal Little Tramp is transmuted into a specifically Jewish barber whose country is about to be absorbed into the totalitarian empire of Adenoid Hynkel."[53] Finally, in A Distant Technology: Science Fiction Film and the Machine Age, J. P. Telotte writes that "The little tramp figure is here reincarnated as the Jewish barber".[54]

A two-page discussion of the relationship between the barber and The Tramp appears in Eric L. Flom's book Chaplin in the Sound Era: An Analysis of the Seven Talkies. He concludes:

Perhaps the distinction between the two characters would be more clear if Chaplin hadn't relied on some element of confusion to attract audiences to the picture. With The Great Dictator's twist of mistaken identity, the similarity between the barber and the Tramp allowed Chaplin break [sic] with his old persona in the sense of characterization, but to capitalize on him in a visual sense. The similar nature of the Tramp and barber characterizations may have been an effort by Chaplin to maintain his popularity with filmgoers, many of whom by 1940 had never seen a silent picture during the silent era. Chaplin may have created a new character from the old, but he nonetheless counted on the Charlie person to bring audiences into the theaters for his first foray into sound, and his boldest political statement to date.[55]

Awards

[edit]The film was nominated for five Academy Awards:

- Outstanding Production – United Artists (Charlie Chaplin, Producer)

- Best Actor – Charlie Chaplin

- Best Writing (Original Screenplay) – Charlie Chaplin

- Best Supporting Actor – Jack Oakie

- Best Music (Original Score) – Meredith Willson

Chaplin also won best actor awards at National Board of Review awards and New York Film Critics Circle Awards.[56]

In 1997, The Great Dictator was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry as being "culturally, historically or aesthetically significant".[5]

In 2000, the American Film Institute ranked the film No. 37 in its "100 Years... 100 Laughs" list.[57]

The film holds a 92% "Fresh" rating on the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes based on 48 reviews, with an average rating of 8.90/10. The consensus reads, "Charlie Chaplin demonstrates that his comedic voice is undiminished by dialogue in this rousing satire of tyranny, which may be more distinguished by its uplifting humanism than its gags."[58] Film critic Roger Ebert of Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four stars out of four and included it in his Great Movies list.[59]

Plagiarism lawsuit

[edit]Chaplin's half-brother Sydney directed and starred in a 1921 film called King, Queen, Joker in which, like Charles Chaplin, he played the dual role of a barber and ruler of a country which is about to be overthrown. More than twenty years later, in 1947, Charles Chaplin was sued over alleged plagiarism with The Great Dictator. Konrad Bercovici claimed that he had created ideas such as Charles Chaplin playing a dictator and a dance with a globe, and that Charles Chaplin had discussed his five-page outline for a screenplay with him for several hours.[36] Yet, apparently, neither the suing party nor Charles Chaplin himself brought up Sydney Chaplin's King, Queen, Joker of the silent era.[60] The case, Bercovici v. Chaplin, was settled, with Charles Chaplin paying Bercovici $95,000 ($1.3 million in 2023).[61] In return, Bercovici conceded that Chaplin was the sole author. Chaplin insisted in his autobiography that he had been the sole writer of the movie's script. He agreed to a settlement, because of his "unpopularity in the States at that moment and being under such court pressure, [he] was terrified, not knowing what to expect next."[62]

Home media

[edit]A digitally restored version of the film was released on DVD and Blu-ray by the Criterion Collection in May 2011. The extras feature color production footage shot by Sydney Chaplin, a deleted barbershop sequence from Charlie Chaplin's 1919 film Sunnyside, a barbershop sequence from Sydney Chaplin's 1921 film King, Queen, Joker, a visual essay by Chaplin biographer Jeffrey Vance titled "The Clown Turns Prophet", and The Tramp and the Dictator (2002), Kevin Brownlow and Michael Kloft's documentary exploring the lives of Chaplin and Hitler, including interviews with author Ray Bradbury, director Sidney Lumet, screenwriter Budd Schulberg, and others. It has a booklet featuring an essay by film critic Michael Wood, Chaplin's 1940 The New York Times defense of his movie, a reprint from critic Jean Narboni on the film's final speech, and Al Hirschfeld's original press book illustrations.[63]

Legacy

[edit]The Great Dictator influenced numerous directors, such as Stanley Kubrick, Mel Brooks, Wes Anderson, and Chuck Jones and inspired such films as The Dictator (2012), The Interview (2014), and Jojo Rabbit (2019).

Sean McArdle and Jon Judy's Eisner Award-nominated comic book The Führer and the Tramp is set during the production of The Great Dictator.[64]

The final speech of the film has been sampled in more than 40 songs,[65] artists such as Coldplay and U2 have played the speech during live shows,[66] and coffee company Lavazza used it in a television advertisement.[67]

During Gorbachev's Perestroyka in the USSR (late 1980s, ended with the downfall of the USSR and its version of Communism in 1991), a movie Repentance was created by a team of Georgians, with primary soundtrack being Georgian, and the Russian soundtrack being secondary "double". The movie was more-or-less directly modeled after The Great Dictator, bearing hardcore anti-Stalinism bias. The dictator protagonist "batono Varlam" (Georgian: "comrade Varlam") was chosen to be facially similar to Lavrenty Beria, the notorious national security minister of late Stalin. The movie, which started the wave of anti-Stalinism in Soviet media and all over the country, is considered to be one of the major milestones of Perestroyka. It was also extremely important that the authors were Georgians, since both Stalin and Beria were Georgians themselves.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Hitler's Reign of Terror (screened 30 April 1934), possibly the first American anti-Nazi film

- Are We Civilized? (released 6 June 1934), about an unspecified dictatorship

- To Be or Not to Be (February 15, 1942), a dark comedy about living in Nazi-occupied Warsaw, remade in 1983 by Mel Brooks

References

[edit]- ^ "The Great Dictator (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. December 9, 1940. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "UA Meeting". Variety. November 20, 1940. p. 20.

- ^ a b Friedman, Barbara G. (2007). From the Battlefront to the Bridal Suite: Media Coverage of British War Brides, 1942-1946. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1718-9.

Charlie Chaplin's 1940 film The Great Dictator, satirizing Hitler and Nazism, grossed $5 million worldwide and became a classic.

- ^ a b c d Branagh, Kenneth (narrator) (2002). Chaplin and Hitler: The Tramp and the Dictator (television). BBC. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ a b "Films Selected to The National Film Registry, 1989–2010". Library of Congress. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ^ "New to the National Film Registry (December 1997) – Library of Congress Information Bulletin". www.loc.gov. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- ^ Chaplin, Charlie (1964). My Autobiography. New York, Simon and Schuster. p. 392.

Had I known of the actual horrors of the German concentration camps, I could not have made The Great Dictator, I could not have made fun of the homicidal insanity of the Nazis

- ^ The spelling of the country's name is derived from the numerous local newspapers flashed onscreen between 14 and 15 minutes into the film that indicate the end of World War I, such as The Tomainian past, thus establishing the proper spelling.

- ^ "The film that dared to laugh at Hitler". BBC Culture. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Pfieffer, Lee. "The Great Dictator". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ^ "The Great Dictator". The Criterion Collection.

- ^ Trimborn, Jürgen (2007). Leni Riefenstahl: A Life. Macmillan. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0-374-18493-3.

- ^ Cole, R. (2001). "Anglo-American Anti-fascist Film Propaganda in a Time of Neutrality: The Great Dictator, 1940"". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 21 (2): 137–152. doi:10.1080/01439680120051488. S2CID 159482040.

[Chaplin sat] for hours watching newsreels of the German dictator, exclaiming: Oh, you bastard, you!

- ^ Ebiri, Bilge (December 19, 2014). "The Interview Has Renewed Interest in Chaplin's The Great Dictator, Which Is a Great Thing". Vulture. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ "Searching for Hitler and His Henchmen: Hitler in the Movies". schikelgruber.net. Archived from the original on October 27, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ Stratton, David (February 21, 2002). "The Tramp and the Dictator". Variety. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ Kamin, Dan; Eyman, Scott (2011). The Comedy of Charlie Chaplin: Artistry in Motion. Scarecrow Press. pp. 154–155. ISBN 978-0-8108-7780-1.

- ^ Singer, Jessica (September 14, 2007). "The Great Dictator". Brattle Theatre Film Notes. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ Internationally co-produced by four production companies, including BBC, Turner Classic Movies, and Germany's Spiegel TV

- ^ "Charlie Chaplins Hitler-Parodie: Führer befiehl, wir lachen!" [Charlie Chaplin's Hitler parody: Fiihrer commands, we laugh!] (in German). May 19, 2010. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- ^ Wallace, Irving; Wallechinsky, David; Wallace, Amy; Wallace, Sylvia (February 1980). The Book of Lists 2. William Morrow. p. 200. ISBN 9780688035747.

- ^ Hoffmann, Frank W.; Bailey, William G. (1992). Mind & Society Fads. Haworth Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-56024-178-2.

Between world wars, Esperanto fared worse and, sadly, became embroiled in political power moves. Adolf Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf that the spread of Esperanto throughout Europe was a Jewish plot to break down national differences so that Jews could assume positions of authority.... After the Nazis' successful Blitzkrieg of Poland, the Warsaw Gestapo received orders to 'take care' of the Zamenhof family.... Zamenhof's son was shot... his two daughters were put in Treblinka death camp.

- ^ a b Meredith Willson (1948). And There I Stood With My Piccolo. Garden City, New York: Doubleday and Company, Inc.

- ^ a b James L. Neibaur (2011). "The Great Dictator". Cineaste. Vol. XXXVI, no. 4. Archived from the original on January 26, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2012.

- ^ Edwards, Bill. "Charles Spencer Chaplin". ragpiano.com. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ "Charlie Chaplin in The Dictator: The Globe Scene using the Prelude to Lohengrin, Act 1" Archived October 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. WagnerOpera.net. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ "Ten Films that Used Wagner's Music", Los Angeles Times. June 17, 2010.

- ^ Peter Conrad. Modern Times, Modern Places How Life and Art Were Transformed in a Century of Revolution, Innovation and Radical Change. Thames & Hudson. 1999, p. 427

- ^ Koepnick, Lutz Peter (2002). The Dark Mirror: German Cinema between Hitler and Hollywood. University of California Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-520-23311-9.

- ^ Waller, J. Michael (2007). Fighting the War of Ideas Like a Real War. Lulu.com. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-615-14463-4.[self-published source]

- ^ Kracauer, Siegfried (1947). From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the Gertman Film. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 248–250. ISBN 0-691-02505-3.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (October 16, 1940). "Still Supreme in 'The Great Dictator,' Charlie Chaplin Reveals Again the Greatness in Himself". The New York Times. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ Ryan Gilbey (2005). The Ultimate Film: The UK's 100 most popular films. London: BFI. p. 240.

- ^ Sackett, Susan (December 26, 1996). "The Hollywood reporter book of box office hits". New York : Billboard Books – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Charles Higham (1971). The Films of Orson Welles. University of California Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-520-02048-1.

- ^ a b Friedrich, Otto (1997). City of Nets: A Portrait of Hollywood in the 1940s (reprint ed.). Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 0520209494.

- ^ Prince of Wales Theatre (2007). Theatre Programme, Mama Mia!. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ French box office in 1945 at Box office story

- ^ "Cahiers du cinéma's 100 Greatest Films". November 23, 2008.

- ^ O'Neill, Phelim (October 18, 2010). "The Great Dictator: No 22 best comedy film of all time". The Guardian. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ "The 100 greatest comedies of all time". BBC Culture. August 22, 2017. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ Vance, Jeffrey (2003). Chaplin: Genius of the Cinema. New York: Harry N. Abrams, p. 250. ISBN 0-8109-4532-0.

- ^ Vance, Jeffrey (2003). "The Great Dictator" (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved April 17, 2024.

- ^ Truffaut, François (1994). The Films in My Life. Da Capo Press. p. 358. ISBN 978-0-306-80599-8.

- ^ "The Great Dictator:The Essentials". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (September 27, 2007). "The Great Dictator (1940) [review]". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

- ^ Weissman, Stephen (2008). Chaplin: A Life. Arcade. ISBN 978-1-55970-892-0.

- ^ Mark Bourne. "The Great Dictator:The Chaplin Collection". DVD Journal. Retrieved December 31, 2010.

- ^ The Scarecrow Video Movie Guide. Sasquatch Books. 2004. p. 808. ISBN 978-1-57061-415-6.

- ^ Insdorf, Annette (2003). Indelible shadows: film and the Holocaust. Cambridge University Press. p. 410. ISBN 978-0-521-01630-8.

- ^ Bernheimer, Kathryn (1998). The 50 greatest Jewish movies: a critic's ranking of the very best. Carol Publishing. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-55972-457-9.

- ^ Schatz, Thomas (1999). Boom and Bust: American Cinema in the 1940s. University of California Press. p. 571. ISBN 978-0-520-22130-7.

- ^ Shindler, Colin (1996). Hollywood in crisis: cinema and American society, 1929–1939. Psychology Press. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-415-10313-8.

- ^ Telotte, J.P. (1999). A distant technology: science fiction film and the machine age. Wesleyan University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-8195-6346-0.

- ^ Flom, Eric (1997). Chaplin in the sound era: an analysis of the seven talkies. McFarland. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-7864-0325-7.

- ^ "Best Actor". nyfcc.

- ^ America's Funniest Movies. AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ^ The Great Dictator at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ "The Great Dictator". Roger Ebert. September 27, 2007.

- ^ Garza, Janiss. "King, Queen, Joker: Synopsis". AllMovie. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ "Chaplin Suit Ends; Actor Pays $95,000 – Agreement in Plagiarism Case Gives Comedian Scenarios Written by Bercovici". The New York Times. May 2, 1947. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ Chaplin, My Autobiography, 1964.

- ^ "The Great Dictator". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ Johnston, Rich (December 22, 2019). "The Fuhrer And The Tramp #1 and Hank Steiner: Monster Detective #1 Launch in Source Point March 2020 Solicits". Bleeding Cool.

- ^ "Final Speech". Whosampled. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ "U2 Concert Intro". charliechaplin.com. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ Greenberg, Charlie (August 19, 2020). "Lavazza channels the 80-year-old words of Charlie Chaplin". The Savvy Screener. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Chaplin and American Culture: The Evolution of a Star Image. Charles J. Maland. Princeton, 1989.

- National Film Theatre/British Film Institute notes on The Great Dictator.

- The Tramp and the Dictator, directed by Kevin Brownlow, Michael Kloft 2002, 88 mn.

External links

[edit]- The Great Dictator essay by Jeffrey Vance on the National Film Registry website

- The Great Dictator essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 320-321

- The Great Dictator at IMDb

- The Great Dictator at AllMovie

- The Great Dictator at the TCM Movie Database

- The Great Dictator at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- The Great Dictator at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Great Dictator: The Joker and the Madman an essay by Michael Wood at the Criterion Collection

- "The Great Dictator (1940) The Screen in Review", Bosley Crowther Wallace, The New York Times, October 16, 1940

- 1940 films

- 1940s war comedy-drama films

- American black-and-white films

- American war comedy-drama films

- American satirical films

- American political comedy-drama films

- American political satire films

- Anti-fascist propaganda films

- Anti-war films about World War II

- Films about Adolf Hitler

- Cultural depictions of Benito Mussolini

- Esperanto-language films

- Films about fascists

- Films directed by Charlie Chaplin

- Films set in 1918

- Films set in Europe

- Films set in fictional countries

- Films set in concentration camps

- Films shot in California

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Military comedy films

- Films involved in plagiarism controversies

- United States National Film Registry films

- Films about dictators

- Films à clef

- Western Front (World War I) films

- 1940s English-language films

- 1940s American films

- Films about lookalikes

- English-language war comedy-drama films