The Interview

| The Interview | |

|---|---|

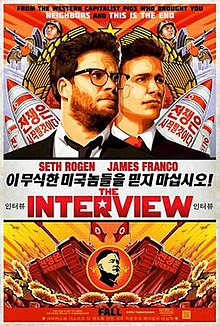

Theatrical release poster[a] | |

| Directed by | |

| Screenplay by | Dan Sterling |

| Story by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Brandon Trost |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Henry Jackman |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Releasing[b] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 112 minutes[3] |

| Countries |

|

| Languages | English Korean |

| Budget | $44 million[4][5] |

| Box office | $12.3 million[6] |

The Interview is a 2014 American political satire[7] action comedy film produced and directed by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg in their second directorial work, following This Is the End (2013). The screenplay was written by Dan Sterling, which he based on a story he co-wrote with Rogen and Goldberg. The film stars Rogen and James Franco as journalists who set up an interview with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, played by Randall Park, only to then be recruited by the CIA to assassinate him.

Rogen and Goldberg developed the idea for The Interview in the late 2000s, with Kim Jong Il as the original assassination target. In 2011, following Kim Jong Il's death and Kim Jong Un's succession as the North Korean leader, Rogen and Goldberg redeveloped the script in order to focus on Kim Jong Un's character. The Interview was first announced in March 2013 at the beginning of pre-production. Principal photography took place in Vancouver from October to December 2013. The film was produced by Columbia Pictures, LStar Capital and Rogen and Goldberg's Point Grey Pictures, and distributed by Sony Pictures Releasing.

In June 2014, the North Korean government threatened action against the United States if Sony released the film. As a result, Sony delayed the film's release from October to December and reportedly reedited the film in order to make it more acceptable to North Korea. In November that year, Sony's computer systems were hacked by the "Guardians of Peace", a cybercrime group allegedly connected to the North Korean government[8] that also threatened terrorist attacks against theaters showing the film. This led to major theater chains opting not to release the film and Sony instead releasing it for online digital rental and purchase on December 24, 2014, followed by a limited release at selected theaters the following day.

The Interview grossed $40 million in digital rentals, making it Sony's most successful digital release and earned an additional $12.3 million worldwide in box office ticket sales on a $44 million budget. It received mixed reviews from critics for its humor and subject matter, although they praised the performances of Franco and Park.

Plot

[edit]Dave Skylark is the host of the popular talk show Skylark Tonight, where he interviews various celebrities (including Eminem and Rob Lowe) about personal topics. The show's broadcast gets interrupted by news reports about North Korea regarding its leader Kim Jong Un and concerns about his nuclear weapons.

After Skylark and his crew celebrate producer Aaron Rapaport's 1,000th episode, Rapaport is upset by a producer peer, who criticizes the show as not being a real news program. After he voices his concern to Skylark and urges change, he agrees and later discovers that Kim is a fan of their show, prompting Rapaport to arrange an interview for him. Traveling to the outskirts of Dandong, China to receive instructions from North Korean chief propagandist Sook-yin Park, Rapaport accepts the interview on behalf of Skylark. Following Rapaport's return, CIA agent Lacey visits the duo and requests that they assassinate Kim with a transdermal strip of ricin via handshake to prevent a possible nuclear launch against the West Coast; they reluctantly agree.

Skylark carries the strip hidden inside a pack of gum. Upon arrival in Pyongyang, the group is greeted by Sook and taken to the palace where they are introduced to Kim's personal security officers Koh and Yu, who are immediately suspicious of them. When Koh finds the strip, he chews it upon mistaking it for gum. After making a secret request for help, Lacey airdrops them two more strips via a drone. However, to get it back to their room, Rapaport is forced to evade a Siberian tiger and hide the container in his rectum, before getting caught and stripped naked by security.

The next day, Skylark meets Kim and spends the day playing basketball, hanging out, riding in his personal tank and partying with a group of escort women. Kim convinces Skylark that he is misunderstood as both a cruel dictator and a failed administrator, and they become friends. At a state dinner, Koh suffers a seizure and diarrhea from the ricin poisoning, accidentally shooting Yu before dying. A guilt-ridden Skylark discards one of the ricin strips the next morning and thwarts Rapaport's attempt to poison Kim with the second strip.

After a dinner mourning the deaths of the bodyguards, Skylark witnesses Kim's brutal self as he angrily threatens South Korean "capitalists", the US and everyone who attempts to undermine his power, and later discovers that Kim has been lying to him upon seeing that the nearby grocery store is fake. At the same time, while seducing Rapaport (who still has the ricin strip on his hand), Sook reveals that she actually despises Kim and apologizes for defending his regime. Skylark returns and tries to get Sook's support to assassinate Kim, but she disagrees, suggesting to instead damage his cult of personality and show the North Korean people the dire state of the country.

The trio secretly devise a plan to expose Kim on-air, arming themselves with guns and Rapaport has sex with Sook. Before the broadcast begins, Kim gifts Skylark a puppy as a symbol of their friendship. During the internationally televised interview with Kim, Skylark addresses increasingly sensitive topics, including the food shortage and US-imposed economic sanctions, then challenges his need for his father's approval. Rapaport take over the control room to fight off the guards trying to cut the broadcast, while Sook attacks the soldiers storming the control room, including killing Kim's high-ranking general.

Initially resistant and rebuffed Skylark's claims, Kim eventually cries uncontrollably and defecates himself after Skylark, having known his fondness for Katy Perry, betrays him by singing "Firework", ruining his reputation. Kim, enraged at Skylark's betrayal, shoots him and vows revenge by preparing the nuclear missiles. Skylark, whose bulletproof vest has saved him, regroups with Rapaport and Sook to escape and hijacks Kim's tank to get to their pickup point, killing several more soldiers in the process. Kim chases the group in a helicopter, only to be shot down by Skylark before he can issue the command to launch the nuclear missile.

With the nuclear threat thwarted, Sook guides Skylark and Rapaport to an escape route, explaining that she has to return to Pyongyang to maintain security. Skylark and Rapaport are later tracked down and rescued by SEAL Team Six members disguised as North Korean soldiers. Back in the US, Skylark writes a book about his experience in North Korea, Rapaport returns to work as a producer and maintains contact with Sook via Skype, and North Korea becomes a denuclearized democracy under Sook's interim leadership.

Cast

[edit]- James Franco as Dave Skylark

- Seth Rogen as Aaron Rapaport

- Lizzy Caplan as Agent Lacey

- Randall Park as Kim Jong Un (credited as "President Kim")

- Diana Bang as Sook-yin Park

- Timothy Simons as Malcolm

- Reese Alexander as Agent Botwin

- Anders Holm as Jake

- Charles Rahi Chun as General Jong

- Ben Schwartz as Darryl

- Zochhia as Florida

The film also features cameo appearances from Eminem, Rob Lowe, Bill Maher, Seth Meyers, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Song Kang-ho, Brian Williams and Scott Pelley. Iggy Azalea, Nicki Minaj, Emma Stone, Zac Efron and Guy Fieri appear in the title card for Skylark Tonight.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg developed the idea for The Interview in the late 2000s, joking about what would happen if a journalist was required to assassinate a world leader.[9] Initially, screenwriter Dan Sterling wrote his script for the film involving a fictional dictator from a fictional country (reminiscent of Sacha Baron Cohen's The Dictator), but Rogen, Goldberg and Sony executives asked him to rewrite the script focusing on Kim.[10] The screenplay was then titled Kill Kim Jong Un.[11] Previous iterations of the story revolved around Kim Jong Il, but the project was put on hold until he died in 2011 and succeeded by his son Kim Jong Un. Development resumed when Rogen and Goldberg realized that Kim was closer to their own age, which they felt was more humorous. To write the story, Rogen, Goldberg and Sterling researched meticulously by reading non-fiction books and watching video footage of North Korea. The script was later reviewed by an employee in the State Department.[12] Rogen and Goldberg aimed to make the project more relevant and satirical than their previous films while still retaining toilet humor.[9] They were pleased when former NBA star Dennis Rodman visited North Korea and met Kim, as it reinforced their belief that the premise of the film was realistic.[9]

In March 2013, it was announced that Rogen and Goldberg would direct a comedy film for Columbia Pictures in which Rogen would star alongside James Franco, with Franco playing a talk-show host and Rogen playing his producer.[13] Rogen and Goldberg were on board to produce along with James Weaver through Point Grey Pictures, while Columbia was said to finance the $30 million budgeted film.[13] Lizzy Caplan joined the film's cast in October 2013. Caplan signed on to play Agent Lacey, a CIA agent who tries to get Franco's character to assassinate Kim.[14] Randall Park and Timothy Simons signed on to co-star later that month. Park starred as Kim and Simons as the director of the talk show.[15][16] Park was the first to audition for the role of Kim Jong Un and got the part immediately. Before filming began, Park gained 15 pounds and shaved his head to resemble Kim's signature crew cut. His role was praised by critics.[9][17] Although Rogen and Goldberg wrote the character of Kim as "robotic and strict", Park instead played it "sheepish and shy", which they found more humorous.[9] Diana Bang was cast as Sook-yin Park, for which she was well-received by critics.[17][18]

Filming

[edit]Principal photography on the film began in Vancouver, British Columbia, on October 10, 2013,[19] and concluded on December 20, 2013.[20] There are hundreds of visual effects in the film; for instance, a crowd scene at the Pyongyang airport was digitally manipulated with a shot from 22 Jump Street.[9]

Pre-release reaction

[edit]In June 2014, The Guardian reported that the film had "touched a nerve" within the North Korean government, as they are "notoriously paranoid about perceived threats to their safety."[21][22] The Korean Central News Agency (KCNA), the state news agency of North Korea, reported that their government promised "stern" and "merciless" retaliation if the film was released. KCNA said that the release of a film portraying the assassination of the North Korean leader would not be allowed and it would be considered the "most blatant act of terrorism and war".[23][24] The next month, North Korea's United Nations ambassador Ja Song-nam condemned the film, describing its production and distribution as "an act of war" and because of Kim's assassination in the film, "the most undisguised sponsoring of terrorism."[25] The Guardian described Song-nam's comments as "perfect publicity for the movie".[25] Later in July, KCNA wrote to U.S. President Barack Obama, asking to have the film pulled.[26] Shortly before the planned release of the film on December 25, 2014, screenwriter Dan Sterling told Creative Screenwriting: "I couldn't believe that the most infamous man in the world knew about my script – but most importantly, I would never want something I wrote to lead to some kind of humanitarian disaster. I would be horrified if anyone got hurt over this."[10]

Release

[edit]Delay and changes

[edit]In August 2014, Sony delayed the film's release from October 10 to December 25, 2014[27] and made post-production alterations to the film in order to modify its portrayal of North Korea, including modifying the designs of buttons worn by characters (which were originally modeled after real North Korean military buttons praising the country's leaders) and cutting a portion of Kim Jong Un's death scene.[28] In December 2014, South Korean singer Yoon Mi-rae revealed that the film used her song "Pay Day" without permission, and that she was taking legal action.[29] Yoon Mi-rae and her label Feel Ghood Music reached a settlement with Sony Pictures Entertainment on May 13, 2015.[30]

Sony Pictures Entertainment hack and threats

[edit]

On November 24, 2014, an anonymous group identifying themselves as the "Guardians of Peace" hacked the computer networks of Columbia Pictures's parent company Sony Pictures Entertainment.[31] The hackers leaked internal emails, employee records and several recent and unreleased Sony Pictures films, including Annie, Mr. Turner, Still Alice and To Write Love on Her Arms. The North Korean government denied involvement in the hack.[32][33][34] On December 8, the hackers leaked further materials, including a demand that Sony pull "the movie of terrorism", widely interpreted as referring to The Interview.[35][36][37]

On December 16, 2014, the hackers threatened to attack the New York premiere of The Interview and any cinema showing the film.[33] Two further messages were released on December 1; one, sent in a private message to Sony executives, said that the hackers would not release further information if Sony never released the film and removed it from the internet. The other, posted to Pastebin, a web application used for text storage which the Guardians of Peace had used for previous messages, stated that Sony had "suffered enough" and could release The Interview, but only if Kim Jong Un's death scene was not "too happy". The message also threatened that if Sony made another film antagonizing North Korea, the hackers "will be here ready to fight".[38]

Distribution

[edit]The Interview was not released in Japan, as live-action comedy films do not often perform well in the Japanese market. In the Asia-Pacific region, it was released only in Australia and New Zealand.[39]

Rogen predicted that the film would make its way to North Korea, stating that "we were told one of the reasons they're so against the movie is that they're afraid it'll actually get into North Korea. They do have bootlegs and stuff. Maybe the tapes will make their way to North Korea and cause a revolution."[9] Business Insider reported via Free North Korea Radio that there was high demand for bootleg copies of the film in North Korea.[40] The South Korean human rights organizations Fighters for a Free North Korea and Human Rights Foundation, largely made up of North Korean defectors, planned to distribute DVD copies of The Interview via balloon drops.[41][42] The groups had previously air-dropped offline copies of the Korean Wikipedia into North Korea on a bootable USB memory device.[43] The balloon drop was scrapped after the North Korean government referred to the plan as a de facto "declaration of war".[44][45]

Cancellation of wide theatrical release

[edit]The film's world premiere was held in Los Angeles on December 11, 2014.[46] The film was scheduled a wide release in the United Kingdom and Ireland on February 6, 2015.[47] Following the hackers' threats on December 16, Rogen and Franco canceled scheduled publicity appearances and Sony pulled all television advertising.[48] The National Association of Theatre Owners said that they would not object to cinema owners delaying the film in order to ensure the safety of filmgoers. Shortly afterwards, the ArcLight and Carmike cinema chains announced that they would not screen the film.[49]

On December 17, Sony canceled the New York City premiere. Later that day, other major theater chains including AMC, Cinemark, Cineplex, Regal, Southern Theatres and several independent movie theaters either delayed or canceled screenings of the film,[50] which led to Sony announcing that they were scrapping the wide theatrical release of the film altogether.[51] The chains reportedly came under pressure from shopping malls where many theaters are located, which feared that the terror threat would ruin their holiday sales. They also feared expensive lawsuits in the event of an attack; Cinemark, for instance, contended that it could not have foreseen the 2012 Aurora, Colorado shooting, which took place at one of its multiplexes, a defense that would not hold in the event of an attack at a screening of The Interview.[52]

In light of the decision by the majority of our exhibitors not to show the film The Interview, we have decided not to move forward with the planned December 25 theatrical release. We respect and understand our partners’ decision and, of course, completely share their paramount interest in the safety of employees and theater-goers. Sony Pictures has been the victim of an unprecedented criminal assault against our employees, our customers, and our business. Those who attacked us stole our intellectual property, private emails, and sensitive and proprietary material, and sought to destroy our spirit and our morale – all apparently to thwart the release of a movie they did not like. We are deeply saddened at this brazen effort to suppress the distribution of a movie, and in the process do damage to our company, our employees, and the American public. We stand by our filmmakers and their right to free expression and are extremely disappointed by this outcome.

The cancellation also affected other films portraying North Korea. An Alamo Drafthouse Cinema location in Dallas planned to hold a free screening of Team America: World Police, which satirizes Kim Jong Un's father Kim Jong Il, in place of its previously scheduled screening of The Interview;[53][54] Paramount Pictures refused to permit the screening.[55] New Regency pulled out of a planned film adaptation of the graphic novel Pyongyang starring Steve Carell; Carell declared it a "sad day for creative expression".[56]

Sony received criticism for canceling the wide release.[57][58][59] Guardian film critic Peter Bradshaw wrote that it was an "unprecedented defeat on American turf", but that "North Korea will find that their bullying edict will haunt them."[60] In the Capital and Gizmodo suggested the cancellation caused a Streisand effect, whereby the attempt to remove or censor a work has the unintended consequence of publicizing it more widely.[61][62] In a press conference, U.S. President Barack Obama said that though he was sympathetic to Sony's need to protect employees, he thought Sony had "made a mistake. We cannot have a society in which some dictator in some place can start imposing censorship in the United States. I wish they'd spoken to me first. I would have told them: do not get into the pattern in which you are intimidated."[63]

According to Sony Pictures Entertainment CEO Michael Lynton, the cancellation of the wide release was a response to the refusal of cinema chains to screen the film, not the hackers' threats, and that Sony would seek other ways to distribute the film. Sony released a statement saying that the company "is and always has been strongly committed to the First Amendment… Free expression should never be suppressed by threats and extortion."[64]

The film was not released in Russia.[65]

Revised release

[edit]After the wide release cancellation, Sony considered other ways to release the film citing pressure from the film industry, theater owners and the White House.[64][66][67] On NBC's Meet the Press on December 21, Sony's legal counsel David Boies noted that the company was still committed to releasing the film.[67] Sony planned a limited release for December 25, 2014, at more than three hundred American independent and arthouse cinemas.[68][69][70][71] Lynton stated that Sony was trying to show the film to the largest audience by securing as many theaters as they could.[69][70]

Sony released The Interview for rental or purchase in the United States through the streaming services Google Play, Xbox Video, and YouTube on December 24, 2014. It was also available for a limited time on SeeTheInterview.com, a website operated by the stealth startup Kernel.com, which Sony previously worked with to market The Fifth Wave.[72] Within hours, The Interview spread to file sharing websites after a security hole allowed people to download rather than stream the film.[73] TorrentFreak estimated that The Interview had been downloaded illegally via torrents at least 1.5 million times in just two days.[74] On December 27, the North Korean National Defence Commission released a statement accusing President Obama of forcing Sony to distribute the film.[75] The film was released on iTunes on December 28.[76]

In the first week of January 2015, Sony announced The Interview would receive a wide theatrical release in the United Kingdom and Ireland on February 6, but it would not be distributed digitally in the UK.[77] The film became available for streaming on Netflix on January 24.[78]

Home media

[edit]Sony released the film on Blu-ray Disc and DVD on February 17, 2015. The home release was packaged as the "Freedom Edition", and included 90 minutes of deleted scenes, behind-the-scenes featurettes, a blooper reel, feature commentary with directors Rogen and Goldberg, and a special episode of Naked and Afraid featuring Rogen and Franco.[79] As of July 21, 2015[update], the film had earned over $6.7 million in sales in the U.S.[80]

Reception

[edit]Box office and online rentals

[edit]The Interview opened to a limited release in the United States on December 25, 2014, across 331 theaters[81] and earned over $1 million on its opening day. Variety called the opening gross "an impressive launch for a title playing in only about 300 independent theaters in the U.S."[82] It went on to earn over $1.8 million in its opening weekend, and by the end of its run on January 25, 2015, had grossed $6.1 million at the box office.[83]

Within four days of its online release on December 24, 2014, The Interview earned over $15 million through online rentals and purchases. It became Sony Pictures' highest-grossing online release, outselling Arbitrage ($14 million), Bachelorette ($8.2 million), and Snowpiercer ($7 million).[84] It was the top-selling Google Play and YouTube film of 2014.[85] By January 20, 2015, the film had earned more than $40 million from online sales and rentals.[86]

Sony expected The Interview to break even through video-on-demand sales and saving millions of dollars on marketing.[87] The National Association of Theatre Owners contended that Sony would lose at least $30 million due to the film's poor box office performance.[88]

Critical response

[edit]On review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a 51% approval rating, based on 154 reviews, with an average rating of 5.70/10. The site's consensus reads: "Unfortunately overshadowed by controversy (and under-screened as a result), The Interview's screenplay offers middling laughs bolstered by its two likable leads."[89] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 52 out of 100, based on 33 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[90]

IGN's Roth Cornet wrote that "though it's unlikely to stand out as one of the shrewdest political satires of its time, [it] is a clever, unrestrained and—most importantly—sidesplitting parody that pokes fun at both a vapid media and one of the world's most dangerous dictators."[91] Edward Douglas of ComingSoon.net said the film was "hilarious, but it will probably get us nuked."[92] Jordan Hoffman of The Guardian gave the film three out of five stars and wrote that "if this unessential but agreeable movie really triggered an international response, this is life reflecting art in a major way."[93]

Scott Foundas of Variety panned the film for being "cinematic waterboarding" and "about as funny as a communist food shortage, and just as protracted", but praised the performances of Randall Park and Diana Bang.[17] Mike Hale of The New York Times also praised Park and Bang, but wrote that "after seeing The Interview and the ruckus its mere existence has caused, the only sensible reaction is amazement at the huge disconnect between the innocuousness of the film and the viciousness of the response."[94]

Political response

[edit]In the wake of the Sony Pictures Entertainment hack, leaks revealed e-mails between Sony Pictures Entertainment CEO Michael Lynton and RAND Corporation defense analyst Bruce Bennett from June 2014. Bennett advised against toning down The Interview's graphic Jong-un death scene, in the hope that it would "start some real thinking in South Korea and, I believe, in the North once the DVD leaks into the North". Bennett expressed his view that "the only resolution I can see to the North Korean nuclear and other threats is for the North Korean government to eventually go away", which he felt would be likeliest to occur following an assassination of Kim. Lynton replied that a senior figure in the United States Department of State agreed. Bennett responded that the office of Robert R. King, U.S. Special Envoy for North Korean Human Rights Issues, had determined that the North Korean statements had been "typical North Korean bullying, likely without follow-up".[95]

In an interview with CNN, Bennett said Lynton sits on the board of trustees of the RAND Corporation, which had asked Bennett to talk to Lynton and give his opinion on the film.[96] Bennett felt The Interview was "coarse" and "over the top", but that "the depiction of Kim Jong-un was a picture that needed to get into North Korea. There are a lot of people in prison camps in North Korea who need to take advantage of a change of thinking in the north." Bennett felt that if the DVD were smuggled into the country it might have an effect "over time".[97] Bennett contacted the Special Envoy for North Korean Human Rights Issues, a personal friend of his, who "took the standard government approach: we don't tell industry what to do".[96] Jen Psaki, then a spokesperson for the United States Department of State, confirmed that Daniel R. Russel, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, had spoken to Sony executives; she reiterated that "entertainers are free to make movies of their choosing, and we are not involved in that".[98]

North Korean state press threatened "merciless" retaliation for his depiction in the film. Seth Rogen responded, "People don't usually wanna kill me for one of my movies until after they've paid 12 bucks for it."[99]

Legacy

[edit]In Greece in April 2017, the film's opening scene, depicting a young girl reciting a poem with hate speech, was mistakenly broadcast in the news bulletin of Alpha TV and the news program Live News on Epsilon TV, as a real-life provocative event against the United States.[100] In response to the backlash on various online newspapers, Antonis Sroiter and Nikos Evangelatos, the hosts of the said programs, apologized in posts they made on their social accounts.[101][102]

See also

[edit]- Assassinations in fiction

- Team America: World Police, another comedy film satirizing North Korea

- The Dictator, a comedy film satirizing Middle Eastern dictators

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Korean text translates as: "The war will begin" (on the missiles and tanks). The Korean text line right beneath the stars' names above the movie title translates to: "Please do not believe these ignorant dishonorable Americans!" while the small text to the left and right of the title translates to the film's title. The fine print at the bottom of the poster reiterates the opening tagline from the top of the poster, translating to: "Awful work by the 'pigs' that created Neighbors and This Is the End".[1]

- ^ All references to Sony Pictures were removed from the final film and marketing.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ Vary, Adam B. (June 11, 2014). "The Poster For Seth Rogen and James Franco's New Comedy Is Filled with Anti-American Propaganda" Archived March 28, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. BuzzFeed. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- ^ Donnelly, Matt (December 12, 2014). "Hack Attack: Sony Orders Its Name Removed from 'Interview' Marketing Materials". TheWrap. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- ^ "The Interview (15)". British Board of Film Classification. November 17, 2014. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- ^ "Sony Weighing Premium VOD Release for 'The Interview' (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. December 17, 2014. Archived from the original on January 16, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ "Sony Could Lose $75 Million on 'The Interview' (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. December 18, 2014. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ "The Interview (2014) – Financial Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on April 22, 2018. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ Holmes, Brent (January 4, 2015). "The Interview: Satire is the Greatest Enemy of Tyrants". westerngazette.ca.

- ^ Gabi Siboni and David Siman-Tov, Cyberspace Extortion: North Korea versus the United States Archived August 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, INSS Insight No. 646, December 23, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Eells, Josh (December 17, 2014). "Seth Rogen at the Crossroads". Rolling Stone (1224/1225). New York City: 52–57, 86. ISSN 0035-791X. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ a b Maroff, Melissa (December 18, 2014). "The Interview: an "Act of War"". Creative Screenwriting. Archived from the original on July 21, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Weinstein, Shelli (February 4, 2015). "Seth Rogen: Censoring North Korea in 'The Interview' 'Seemed Wrong'". Variety. Archived from the original on February 5, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ Demick, Barbara (January 2, 2015). "A North Korea Watcher Watches "The Interview"". newyorker.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ a b Siegel, Tatiana (March 21, 2013). "Seth Rogen to Direct, Star in 'The Interview' for Columbia Pictures (Exclusive)". hollywoodreporter.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ Kit, Borys (October 1, 2013). "Lizzy Caplan Joins Seth Rogen and James Franco in 'The Interview'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved December 25, 2013.

- ^ Siegel, Tatiana (October 8, 2013). "Randall Park and 'Veep's' Timothy Simons to Co-Star in Seth Rogen's 'The Interview'". hollywoodreporter.com. Archived from the original on April 20, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ Mazza, Ed (June 25, 2014). "North Korea Calls Seth Rogen-James Franco Film An 'Act Of War'". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ a b c Foundas, Scott (December 12, 2014). "Film Review: 'The Interview'". Variety. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ^ Smith, Krista (November 20, 2014). "The Interview Actress Diana Bang Is Ready for Anything". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Schaefer, Glen (October 12, 2013). "Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg come home to shoot B.C. for Korea in The Interview". The Province. Archived from the original on December 26, 2013. Retrieved December 25, 2013.

- ^ Vlessing, Etan (September 30, 2013). "Seth Rogen, Evan Goldberg to Direct 'The Interview' in Vancouver". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved December 25, 2013.

- ^ McCurry, Justin (June 25, 2014). "North Korea threatens 'merciless' response over Seth Rogen film". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017.

- ^ Branigan, Tanya (December 18, 2014). "Sony's cancellation of The Interview surprises North Korea-watchers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- ^ "North Korea calls new Seth Rogen film, The Interview, an 'act of war'". CBC News. June 25, 2014. Archived from the original on June 26, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ^ "North Korea threatens war on US over Kim Jong-un movie". BBC. June 25, 2014. Archived from the original on June 25, 2014. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ^ a b Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (July 10, 2014). "North Korea complains to UN about Seth Rogen comedy The Interview". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 30, 2014. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ Ryall, Julian (July 17, 2014). "North Korea appeals to White House to halt release of US comedy film". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ Lang, Brent (August 7, 2014). "'The Interview' with Seth Rogen, James Franco Pushed Back to Christmas". Variety. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ^ Siegel, Tatiana (August 13, 2014). "Sony Altering Kim Jong Un Assassination Film 'The Interview'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on August 15, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ "Yoon Mi Rae to Take Legal Action against Sony Pictures for Using Her Song in "The Interview" without Permission". Soompi. December 27, 2014. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ^ "Sony And Yoon Mi Rae Reach Settlement Over Unlicensed Song Usage In 'The Interview'". KpopStarz. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ Sanger, David E.; Perlroth, Nicole (December 17, 2014). "U.S. Said to Find North Korea Ordered Cyberattack on Sony". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014.

- ^ McCurry, Justin (December 4, 2014). "North Korea denies hacking Sony Pictures". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ a b "Hackers who targeted Sony invoke 9/11 attacks in warning to moviegoers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ "Sony's New Movies Leak Online Following Hack Attack". NBC News. December 2014. Archived from the original on December 2, 2014. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ^ Weise, Elizabeth (December 9, 2014). "Hackers told Sony to pull 'The Interview'". USA Today. Archived from the original on November 30, 2015.

- ^ "North Korean Government Thought To Be Behind Sony Pictures Hack". NPR. December 1, 2014. Archived from the original on April 24, 2015.

- ^ "North Korea's Cyber Skills Get Attention Amid Sony Hacking Mystery". NPR. December 4, 2014. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015.

- ^ Weise, Elizabeth; Johnson, Kevin (December 19, 2014). "Obama: Sony "did the wrong thing" when it pulled movie". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 19, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ^ Schilling, Mark (December 10, 2014). "'The Interview' to Have Only Limited Release in Asia". Variety. Archived from the original on December 13, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ Kim, Eugene. "Demand For 'The Interview' Is Shooting Up In North Korea And Its Government Is Freaking Out". Business Insider. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ Bond, Paul (December 16, 2014). "Sony Hack: Activists to Drop 'Interview' DVDs Over North Korea Via Balloon". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ "Launching Balloons into North Korea: Propaganda Over Pyongyang". VICE news. March 18, 2015. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015.

- ^ Segall, Laurie (December 18, 2014). "Activists plan to drop 'Interview' DVDs in North Korea". CNN. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- ^ "South Korean activists postpone sending of copies of The Interview to North Korea by balloon". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. March 24, 2015. Archived from the original on March 23, 2015.

- ^ Mohney, Gillian (March 23, 2015). "North Korea Calls Planned Balloon Drop of 'The Interview' DVDs a 'De Facto Declaration of War'". VICE News. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015.

- ^ Appelo, Tim (December 11, 2014). "'The Interview' Premiere: Seth Rogen Thanks Amy Pascal "For Having The Balls to Make This Movie"". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ Jaafar, Ali (January 7, 2015). "'The Interview' To Get Wide Release In The UK". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on January 10, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ "Seth Rogen and James Franco Cancel All Media Appearances for 'The Interview'". Variety. December 16, 2014. Archived from the original on December 16, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Yamato, Jen; Patten, Dominic (December 17, 2014). "First Theaters Cancel 'The Interview' After Hacker Threats". Deadline. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ "Major U.S. Theaters Drop 'The Interview' After Sony Hacker Threats". Variety. December 17, 2014. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (December 17, 2014). "It's Official: Sony Scraps 'The Interview'". Deadline. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks; Cieply, Michael (December 18, 2014). "Sony Drops 'The Interview' Following Terrorist Threats". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 29, 2017.

- ^ "Texas Theater to Show 'Team America' In Place of 'The Interview'". The Hollywood Reporter. December 17, 2014. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ "'Team America: World Police' Replaces 'The Interview' at Dallas Theater". Variety. December 18, 2014. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ "Paramount Cancels 'Team America' Showings, Theaters Say". Deadline Hollywood. December 18, 2014. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ "Steve Carell's North Korea movie from Guy Delisle novel scrapped after Sony hack". CBC News. Archived from the original on December 19, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ^ Sinha-Roy, Piya (December 17, 2014). "Hollywood slams Sony, movie theaters for canceling 'The Interview'". Reuters. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- ^ Marcus, Stephanie (December 17, 2014). "Celebrities React To Sony Canceling 'The Interview' Release". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014.

- ^ "Hollywood Hits Twitter To Vent Anger About 'The Interview' Being Pulled". Deadline. December 17, 2014. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (December 18, 2014). "The Interview: Sony's retreat signals an unprecedented defeat on American turf". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 19, 2016.

- ^ Schwartz, Eric Hal (December 15, 2014). "Sony Pictures Is in for a Lesson on the Streisand Effect". In The Capital. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- ^ "The Streisand Effect and Why We All Now Want to See 'The Interview'". Gizmodo.co.uk. December 22, 2014. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ^ Dwyer, Devin; Bruce, Mary (December 19, 2014). "Sony Hacking: President Obama Says Company Made 'Mistake' in Canceling 'The Interview'". ABC News. Archived from the original on December 19, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Siegel, Tatiana; Hayden, Erik (December 19, 2014). "Sony Fires Back at Obama: "We Had No Choice" But to Cancel 'The Interview' Release". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on December 24, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ^ Tokmasheva, Maria (January 30, 2018). "Final cut: Movies that have been banned in Russia". Russia Beyond. Archived from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ "Obama: Sony 'Made a Mistake' By Pulling 'The Interview' Movie". NBC News. December 19, 2014. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- ^ a b Atkinson, Claire (December 23, 2014). "Sony faces pressure to release 'The Interview'". New York Post. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ Shaw, Lucas (December 23, 2014). "Sony to Release The Interview in More Than 300 Theaters on Christmas Day" Archived December 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Bloomberg. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- ^ a b "'The Interview' Release Back On For Christmas Day – Update". Deadline Hollywood. December 23, 2014. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ a b Pankratz, Howard (December 23, 2014). "Alamo Drafthouse in Littleton will screen 'The Interview' starting Christmas". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ 'Hobbit' rules box office, 'Interview' succeeds online Archived September 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. USA Today. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ "What is Kernel? The Stealth Startup Sony Tapped to Stream 'The Interview' (Exclusive)". Variety. December 24, 2014. Archived from the original on December 30, 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ "Oops: people are downloading and keeping Sony's rental for The Interview". The Verge. December 24, 2014. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- ^ "The Interview Is A Pirate Hit With 200k Downloads (Updated)". TorrentFreak. Archived from the original on December 28, 2014. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ "North Korea berates Obama over The Interview release". BBC News. December 27, 2014. Archived from the original on December 28, 2014. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ "The Interview makes over $15 million online, beating movie theaters". The Verge. December 28, 2014. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ^ "The Interview to receive UK release, Sony confirms". BBC News. January 7, 2015. Archived from the original on January 10, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2015.

- ^ "'The Interview' is on Netflix streaming". engadget.com. January 24, 2015. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016.

- ^ Welch, Chris (January 14, 2015). "The Interview is coming to Blu-ray and DVD on February 17th". The Verge. Archived from the original on January 16, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ "The Interview (2014)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ de Moraes, Lisa; Andreeva, Nellie (December 24, 2014). "'The Interview' Release: 331 Theaters Aboard For Christmas Day". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ^ McNarry, Dave (December 26, 2014). "Box Office: 'The Interview' Earns $1 Million on Christmas; 'Unbroken,' 'Into the Woods' Surging to $40M". Variety. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ^ Subers, Ray (December 28, 2014). "Weekend Report (cont.): Huge Limited Debuts for 'American Sniper,' 'Selma'". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ Lang, Brent (December 28, 2014). "Sony: 'The Interview' Has Made Over $15 Million Online". Variety. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ The Year's top-selling movie on YouTube, Google Play Archived December 31, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 31, 2014.

- ^ Lang, Brent (January 20, 2015). "'The Interview' Makes $40 Million Online and On-Demand". Variety. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2015.

- ^ Faughdner, Ryan (January 14, 2015). "Sony's 'The Interview' to get 'freedom edition' home video release". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 17, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (January 16, 2015). "'The Interview' Lost Sony $30 Million, Says Theater Group". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 20, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ "The Interview (2014)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ "The Interview". Metacritic. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ "The Interview Review". IGN.com.[dead link]

- ^ "The Interview Review". ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014.

- ^ Hoffman, Jordan (December 12, 2014). "The Interview review: stoned, anally fixated – and funny". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ^ "Memo to Kim Jong-un: Dying Is Easy, Comedy Is Hard". The New York Times. December 19, 2014. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ^ Boot, William (December 17, 2014). "Exclusive: Sony Emails Say State Department Blessed Kim Jong-Un Assassination in 'The Interview'". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014.

- ^ a b "Expert on N. Korea on 'The Interview'". CNN. December 19, 2014. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014.

- ^ "'The Interview' Release Would Have Damaged Kim Jong Un Internally, Says Rand Expert Who Saw Movie At Sony's Request". Yahoo Movies UK. December 19, 2014. Archived from the original on December 23, 2014.

- ^ "Daily Press Briefing – December 17, 2014". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ "North Korea threatens war on US over Kim Jong-un movie". BBC News. June 25, 2014. Archived from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ "Ευαγγελάτος και Alpha παρουσιάζουν σκηνή κωμικής ταινίας για τη Β.Κορέα ως πραγματική" [Evangelatos and Alpha present scene of a comedy film about North Korea as a real-life event]. The Press Project (in Greek). April 21, 2017. Archived from the original on August 2, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- ^ "Ο Νίκος Ευαγγελάτος ζητά συγγνώμη για την γκάφα: Κάναμε λάθος" [Nikos Evangelatos apologizes for the blunder: We made a mistake]. To Pontiki (in Greek). April 21, 2017. Archived from the original on July 21, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- ^ "Η… απολογία Σρόιτερ για το ρεπορτάζ με το κοριτσάκι από τη Βόρεια Κορέα" [Sroiter's... apology for the reportage with the girl from North Korea]. Eleftheros Typos (in Greek). April 22, 2017. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

External links

[edit]- 2014 films

- 2014 action comedy films

- 2014 black comedy films

- 2014 controversies in the United States

- 2010s American films

- 2010s buddy comedy films

- 2010s English-language films

- 2010s Korean-language films

- 2010s political comedy films

- 2010s political satire films

- American action comedy films

- American black comedy films

- American buddy comedy films

- American political comedy films

- American political satire films

- Censored films

- Columbia Pictures films

- Cultural depictions of Kim Jong Un

- Events relating to freedom of expression

- Films about assassinations

- Films about the Central Intelligence Agency

- Films about journalism

- Films about the Korean People's Army

- Films critical of communism

- Films directed by Evan Goldberg

- Films directed by Seth Rogen

- Films produced by Evan Goldberg

- Films produced by Seth Rogen

- Films scored by Henry Jackman

- Films set in 2014

- Films set in China

- Films set in Liaoning

- Films set in Manhattan

- Films set in Nevada

- Films set in North Korea

- Films set in Pyongyang

- Films set in South Korea

- Films set in Virginia

- Films shot in Vancouver

- Films with screenplays by Evan Goldberg

- Films with screenplays by Seth Rogen

- Mass media-related controversies in the United States

- North Korea–United States relations

- Point Grey Pictures films

- Political controversies in film

- Political controversies in the United States

- Self-censorship

- English-language black comedy films

- English-language action comedy films

- English-language buddy comedy films