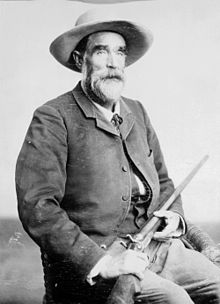

Tom Jeffords

Thomas Jefferson Jeffords | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 1, 1832 |

| Died | February 19, 1914 (aged 82) Tortolita Mountains north of Tucson, Arizona |

| Resting place | Evergreen Cemetery, Tucson, Arizona |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | US Army Scout, Indian agent, prospector |

| Years active | 1876–1903 |

| Employer | Pinkerton Detective Agency |

| Known for | Brokering peace with Apache Chief Cochise |

Thomas Jefferson Jeffords (January 1, 1832 – February 19, 1914) [1] was a United States Army scout, Indian agent, prospector, and superintendent of overland mail in the Arizona Territory. His friendship with Apache leader Cochise was instrumental in ending the Indian wars in that region.[2] He first met Cochise when he rode alone into Cochise's camp in 1871 to request that the chief come to Canada Alamosa for peace talks. Cochise declined at least in part because he was afraid to travel with his family after the recent Camp Grant Massacre. Three months later he made the trip and stayed for over six months during which time their friendship grew while the negotiations failed. Cochise was unwilling to accept the Tularosa Valley as his reservation and home. In October 1872, Jeffords led General Oliver O. Howard to Cochise's Stronghold, believed to be China Meadow, in the Dragoon Mountains. Cochise demanded and got the Dragoon and Chiricahua Mountains as his reservation and Tom Jeffords as his agent. From 1872 to 1876, there was peace in southern Arizona. Then renegade Apaches killed Nicholas Rogers who had sold them whiskey and the cry went out to abolish the reservation and remove Jeffords as agent. Tom Jeffords embarked on a series of ventures as sutler and postmaster at Fort Huachuca, head of the first Tucson water company trying to bring artesian water to that city, and as prospector and mine owner and developer. He died at Owl Head Buttes in the Tortolita Mountains 35 miles north of Tucson.[3]

Early life

[edit]Tom Jeffords was born in Chautauqua County, New York, where his father was trying to earn enough money to purchase a farm. When Tom was seven, the family moved to Ashtabula, Ohio, in the Western Reserve. Jeffords and his brothers sailed the Great Lakes, Tom becoming a captain while still in his early twenties. Bored and in search of wealth, Tom followed the gold rush to Pike's Peak in 1859, working on the road from Leavenworth to Denver. From there. he pursued the San Juan Gold Rush of 1860 to Taos County, New Mexico, and that same year followed the Colorado Gold Rush to Gila City in Arizona. He soon moved on to the mines in Pinos Altos, New Mexico. The Civil War found Tom near Fort Craig and he participated in the Battle of Valverde as a civilian courier. Jeffords accepted an assignment from Colonel Edward Canby to ride over 500 miles alone across Apache country to Fort Yuma, California, where Colonel James Carleton was arriving with the California Column. Since Confederate forces had invaded southern New Mexico and occupied the countryside as far as Tucson, Colonel Canby needed a brave courier who knew the route through the wilds along the Gila River. Tom Jeffords returned east to Arizona Territory in 1862 as a scout with the lead companies of the California Column. He remained with the Army as a civilian scout throughout the war as the Army engaged Navajo, Apache and Comanche Indians and kept the Texans out of New Mexico.[3]

Bascom Affair

[edit]Open war with the Chiricahua Apaches had begun in 1861, when Cochise, one of their chiefs, was accused by the Army of kidnapping an 11-year-old Mexican boy, Felix Ward, stepson of Johnny Ward, later known as Mickey Free. Although the abduction was probably the work of Pinal Indians, a clear trail led to Cochise's doorstep. Reassignment of two companies of dragoon cavalry to Fort Breckinridge on the lower San Pedro River had forced the Pinal, Coyotero and other Western Apaches to alter their raiding routes so that they swung east toward the Chiricahua Mountains and Apache Pass.[4]

Lieutenant George Nicholas Bascom was sent with 66 men of Company C, 7th Infantry, which he commanded, to get the boy back. Johnny Ward went along as interpreter. The lieutenant invited Cochise to his camp for parley and they retired to the lieutenant's tent for lunch and talk along with his brother, Coyuntura, and Ward. Bascom told Cochise that he wanted the boy and Ward's stolen livestock.[4]

This was not the first time that Cochise had been forced to return stolen stock. Captain Richard S. Ewell had been out to Apache Pass twice before to recover stock and had sworn he would, "proceed to force them to terms the next time".[5]

Cochise said he did not have them but thought he knew who did. Bascom told the chief he would be a hostage against the boy's safe return. Cochise's father and brothers had been slain by Mexicans during parley and his people had been poisoned. Hearing that he would be a hostage, Cochise pulled his knife, slashed the ties of the tent, and escaped up Overlook Ridge. His brother, his son and nephew, two warriors and his wife remained as hostages.[4]

Meeting the next day, Cochise violated the flag of truce and took his own hostage. In following days, he took three more. Surrounded by what he believed were 500 Apaches, Bascom sent for aid. The first to arrive was Surgeon Bernard Irwin, who took three more hostages on his way to rescue Bascom while leading only eleven men. He was awarded the Medal of Honor 32 years later for this action.[6]

Cochise killed and possibly tortured his four hostages. Two troops of dragoons arrived under command of Lieutenants Isaiah Moore and Richard Lord, both senior to Bascom. Moore took command. Irwin proposed hanging the six Apache hostages (the woman and boys were released at Fort Buchanan).[6] Bascom demurred but, outranked, allowed the hanging.[7]

Cochise, formerly inclined toward peace with the white settlers, now joined other Apache chiefs in hostility to them. It was not long before the Army retaliated, and the war was on.[8]

Between 1867 and 1869, Jeffords was the superintendent of a mail line from Tucson to Socorro. He apparently gave people to understand that he had met Cochise during this period and negotiated a peace for his mail riders. This is very unlikely as they were attacked as often, seldom, after he took charge as before.[3]

In 1871 President Grant sent General Oliver Howard to the Arizona Territory with orders to end the Apache wars by negotiating treaties with the tribes. Howard was an apt choice, as he had been head of the Freedmen's Bureau, the agency responsible for assisting freed black slaves after the Civil War. General Howard enlisted the help of Jeffords in concluding these treaties. Learning of his work with the Freedmen's Bureau, Jeffords knew that Howard was honorable and would be respected by Cochise, and eventually conducted the general into Cochise's camp. A treaty was signed in 1872, ending the decade-long war with the Chiricahua Apaches.[9]

On December 14, 1872, 18th President of the United States Ulysses Grant issued an Executive Order establishing the Chiricahua Reservation in the southeast Arizona Territory at the Mexico–United States border and New Mexico Territory border.[10][11] Cochise requested that his people be allowed to remain in the Chiricahua Mountains and that Jeffords be made Indian agent for the region. These requests were granted, and the Indian raids subsided.[12]

Settlers branded Jeffords "Indian lover" and wrote scathing reports to politicians back in Washington.[3] In 1875, he was removed as the federal agent and the Chiricahua Apaches were relocated to the San Carlos Reservation.[13] Cochise was spared this; he had died of natural causes about a year after signing the now broken treaty. The Apache wars began again, but were ended in 1886 with the surrender of Geronimo, the last Apache leader.[14]

Later life and death

[edit]Jeffords relocated to Tombstone, AZ, where he was part owner of a number of mines. He staked claims in the Huachuca, Dos Cabezas, and Chiricahua Mountains. With Nicholas Rogers and Sidney De Long, he staked a claim to the famed Brunckow Mine in 1875 and remained in control of it into the 1880s.[15] He was a partner in a mine in Santa Rita, NM and head of a company trying to supply water to the city of Tucson, AZ.[16] He lived out the last 22 years of his life in the Tortolita Mountains north of Tucson, at a homestead near the Owlhead Buttes. He died on February 19, 1914, and was buried in Tucson's Evergreen Cemetery.[7]

A monument was dedicated to Jeffords in Evergreen Cemetery in 1964.[3]

In popular culture

[edit]The story of Jeffords, General Howard, Cochise, and the Apache wars was told in historically-based but dramatized form in a novel by Elliott Arnold called Blood Brother. The novel was adapted into the Delmer Daves's film Broken Arrow (1950). James Stewart played Jeffords in the movie.[17] It was later adapted into a 1956 television show that ran for 72 episodes, in which John Lupton played Jeffords.[18]

References

[edit]- ^ A: Dan L. Thrapp: Al Sieber Chief of Scouts, page 218

B: Dito: The Conquest of Apacheria, page 145

C: Arizona Daily Star, Tucson on February 20, 1914

D: His biography show the February 19, 1914 as date of death.

E: also this biography of Access Genealogy - ^ "Tom Jeffords: Indian Agent" by Harry G. Cramer III (Tucson: Journal of Arizona History, Autumn, 1976, pp. 265–300)

- ^ a b c d e Sonnichsen, Charles Leland (1988). "Who was Tom Jeffords". Pilgrim in the sun: a southwestern omnibus. Texas Western Press. pp. 88–99.

- ^ a b c Hutton, Paul Andrew (May 3, 2016). The Apache Wars: The Hunt for Geronimo, the Apache Kid, and the Captive Boy Who Started the Longest War in American History. Crown/Archetype. pp. 41–44. ISBN 978-0-7704-3582-0.

- ^ Pfanz, Donald C. (November 9, 2000). Richard S. Ewell: A Soldier's Life. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 109–116. ISBN 978-0-8078-8852-0.

- ^ a b Thrapp, Dan L. (August 1, 1991). Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography: G-O. University of Nebraska Press. p. 707. ISBN 0-8032-9419-0.

- ^ a b McLoughlin, Denis (1977). The Encyclopedia of the Old West. Taylor & Francis. pp. 256–257. ISBN 978-0-7100-0963-0.

- ^ Mort, Terry (April 2, 2013). The Wrath of Cochise: The Bascom Affair and the Origins of the Apache Wars. Pegasus Books. pp. 10–12. ISBN 978-1-4532-9847-3.

- ^ Sweeney, Edward R (2008). Making Peace with Cochise: the 1872 Journal of Captain Joseph Alton Sladen. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 120–126. ISBN 978-0-8061-2973-0.

- ^ Grant, Ulysses S. (1912). "Chiricahua Reservation ~ December 14, 1872" [Executive Orders Relating to Indian Reserves, from May 14, 1855, to July 1, 1902]. Internet Archive. United States Government Printing Office. pp. 5–6. LCCN 34008449.

- ^ "Territory of Arizona Map, 1876". United States Library of Congress. United States General Land Office. LCCN 99446141.

- ^ Wyatt, Edgar (1953). Cochise, Apache warrior and statesman. Whittlesey House. pp. 118–123.

- ^ Grant, Ulysses S. (1912). "Executive Order of December 14, 1872 ~ Chiricahua Reservation Lands Restored to Public Domain - October 30, 1876" [Executive Orders Relating to Indian Reserves, from May 14, 1855, to July 1, 1902]. Internet Archive. United States Government Printing Office. p. 6. LCCN 34008449.

- ^ Roberts, David (1994). Once They Moved Like The Wind: Cochise, Geronimo, And The Apache Wars. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 375. ISBN 978-0-671-88556-4.

- ^ Shillingberg, Wm. B. (February 19, 2016). Tombstone, A.T.: A History of Early Mining, Milling, and Mayhem. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 19–20, 75, 86. ISBN 978-0-8061-5409-1.

- ^ Sonnichsen (1962). The Journal of Arizona History. Vol. 4. Tucson, Arizona: Arizona Pioneers' Historical Society. p. 75.

- ^ Stone, Barry (August 4, 2016). The 50 Greatest Westerns. Icon Books. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-1-78578-159-9.

- ^ Terrace, Vincent (November 7, 2013). Television Introductions: Narrated TV Program Openings since 1949. Scarecrow Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-8108-9250-7.