Titivillus

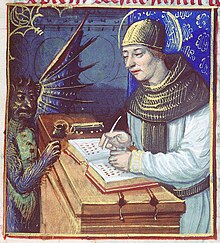

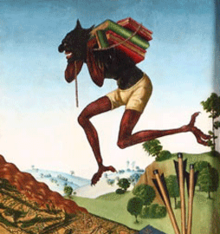

Titivillus is a demon said to introduce errors into the work of scribes. The first reference to Titivillus by name occurred in Tractatus de Penitentia, c. 1285, by Johannes Galensis (John of Wales).[a] Attribution has also been given to Caesarius of Heisterbach. Titivillus has also been described as collecting idle chat that occurs during church service, and mispronounced, mumbled or skipped words of the service, to take to Hell to be counted against the offenders.[citation needed]

He has been called the "patron demon of scribes", as Titivillus provides an easy excuse for the errors that are bound to creep into manuscripts as they are copied.[b]

Marc Drogin noted in his instructional manual, Medieval Calligraphy: Its History and Technique (1980), that "for the past half-century every edition of The Oxford English Dictionary has listed an incorrect page reference for, of all things, a footnote on the earliest mention of Titivillus."

Titivillus gained a broader role as a subversive figure of physical comedy, with satirical commentary on human vanities, in late medieval English pageants, such as the Iudicium that finishes the Towneley Cycle.[4] He plays an antagonistic role in the Medieval English play Mankind.

In an anonymous fifteenth-century English devotional treatise, Myroure of Oure Ladye, Titivillus introduced himself thus (I.xx.54): "I am a poure dyuel, and my name ys Tytyvyllus ... I muste eche day ... brynge my master a thousande pokes full of faylynges, and of neglygences in syllables and wordes."

Origin of the name

[edit]The function of collecting liturgical errors in a sack was first mentioned in by Jacques de Vitry (died 1240) in Sermones vulgares (tenth sermon, on Numbers 18:5), which speaks of a demon that listens to the choir singing psalms and collects syncopated or omitted syllables in a sack.

I have heard that a certain holy man, while in the choir, saw a devil truly weighed down with a full sack. When, however, he commanded the demon to tell what he carried, the evil one said: "These are the syllables and syncopated words and verses of the psalms which these very clerics in their morning prayers stole from God; you can be sure I am keeping these diligently for their accusation."[5][6]

This demon was later given the name "Titivillus" by Johannes Galensis c. 1285.[7] "Titivillus collects fragments of words and puts them in his bag thousand times every day." (Fragmina verborum Titivillus colligit horum quibus die mille vicibus se sarcinat ille).[8]

Regarding the demon's function, André Vernet points out that the Latin terms, particularly "collect" (colligere) and "fragments" (fragmenta) for the clery's omissions, derive from John 6:12, the Feeding the multitude narrative, in which the disciples are told to "Gather up the broken pieces (Colligite fragmenta)." As to the demon's name, Titivillus, Vernet points to The City of God (Book IV, Chapter 8), in a passage in which Augustine, while giving examples of the numerous Roman deities assigned to each step of the agricultural process, mentions a goddess Tutilina whose job is to watch over grain after it was collected and stored. However, we must imagine a series of copyists' errors (perhaps in the copy of City of God available to Johannes Galensis) to arrive at "Titivillus" and its many variants: Tutivillus, Tytivillum, Tintillus, Tantillus, Tintinillus, Titivitilarius, Titivilitarius.[9]

In popular culture

[edit]Since 1977, one of the many devils populating the role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons is named "Titivilus."

He was the subject of the book Tittivulus or The Verbiage Collector by Michael Ayrton (Max Reinhardt: London, 1953).[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Printer's devil

- Wicked Bible

- Uli der Fehlerteufel

- Daemones Ceramici – Greek mythological spirits

Notes

[edit]- ^ Little is known of Johannes Galensis aside from this text and a set of Decretales intermediæ.

- ^ For a twentieth-century subversive demon of mechanical failures, compare gremlin.

References

[edit]- ^ Aragonés Estella, Esperanza (2006). "Visiones de tres diablos medievales". De Arte (5): 15. doi:10.18002/da.v0i5.1543. hdl:10612/1190.

- ^ Esquivias, Óscar: "Diabluras", Diario de Burgos, 15 de diciembre de 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Tolnay, Charles de. Hieronymus Bosch. Het volledige werk, 1984, pp. 35–36.

- ^ The numerous appearances of Titivillus in the Towneley Iudicium are noted in Hicks, James E. (1990). "Majesty and Comedy in the Towneley "Iudicium": The Contribution of Property to Spectacle". Rocky Mountain Review of Language and Literature. 44 (4): 211–228. doi:10.2307/1346789. JSTOR 1346789.

- ^ Jennings, Margaret (November 1977). "Tutivillus: The literary career of the recording demon". Studies in Philology. 74 (5): 11. JSTOR 4173953. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

- ^ A slightly different translation is given in The Exempla of Illustrative Stories from the Sermones Vulgares of Jacques de Vitry, ed. and trans. by T. S. Crane (New York: B. Franklin, 1971), p. 141.

- ^ Johannes Galensis, Tractatus de penitentia, c. 1285 in London, British Library MS Royal 10 A. ix, fol. 40v

- ^ Item 9908 in Walther, H. (1964). Proverbia sententiaeque Latinitatis medii aevi. Lateinische Sprichwörter und Sentenzen des Mittelalters in alphabetischer Anordnung (Teil 2). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- ^ Vernet, André (1958–1959). "Titivillus, "démon des copistes"". Bulletin de la Société Nationale des Antiquaires de France. 1958: 155–157. doi:10.3406/bsnaf.1959.5965. Retrieved July 31, 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Drogin, Marc, Medieval Calligraphy: Its History and Technique, Dover Publications, 1980. ISBN 0-486-26142-5

- Who is Titivillus?

- Montañés, J. G, Tutivillus. El demonio de las erratas, Madrid, Turpin, 2015.

- Montañés, J. G, Titivillus. Il demone dei refusi, Perugia, Graphe.it, 2018