Thomas Eyre Macklin

Thomas Eyre Macklin | |

|---|---|

Macklin in 1922 | |

| Born | March 30, 1863 Newcastle upon Tyne, England |

| Died | August 1, 1943 (aged 80) Budleigh Salterton, Devon, England |

| Alma mater | Royal Academy Schools |

| Notable work | |

| Movement |

|

| Spouse | Alice Martha "Alys" Philpott (writer) |

| Elected | Royal Society of British Artists (RBA), 1900 |

Thomas Eyre Macklin RBA (30 March 1863 – 1 August 1943) was a British painter in oils and watercolour, illustrator, sculptor and designer of monuments, who signed his works T. Eyre Macklin or T.E. Macklin.

After a promising career at various art schools, including the Royal Academy, in the late 19th century Macklin produced Romantic black-and-white illustrations for books, numerous landscapes, figurative paintings and civic portraits, all of which came to the attention of local newspapers in his native Newcastle upon Tyne. In the 20th century he concentrated on Art Deco monuments and other sculpture, his best-known works being the South African War Memorial in Newcastle, the Bangor Memorial, County Down, and the Land Wars Memorial at Auckland, New Zealand.

According to Macklin, his ancestors were from County Donegal. He was the son of John Eyre Macklin, a soldier, journalist and landscape painter; both were Newcastle-born. Macklin married writer Alice Martha "Alys" Philpott and they had one child, but she later petitioned for divorce on the grounds of infidelity. He had bouts of illness during later life and died in Devon in 1943.

Background

[edit]Parentage

[edit]According to Thomas Eyre Macklin, he was "descended from an old Donegal family".[1][2] He was born in Newcastle upon Tyne on 30 March 1863,[nb 1][3][4] the son of Lieutenant John Eyre Macklin (b. Newcastle c.1834) a non-commissioned officer of the 10th Brigade, Royal Artillery, on foreign service (1853–1870). J.E. Macklin was a lieutenant of the English Garibaldian Volunteers (1860–1861),[5] and he was a landscape painter and Newcastle journalist.[nb 2][3][4][12][13] Macklin's mother was Margaret E. Charlton (Carlisle c.1838 – Belfast 30 September 1924).[nb 3][3][14][15] She was the adopted child of an agricultural labourer.[nb 4][16]

Training

[edit]Encouraged by his father, Macklin "showed a remarkable aptitude for drawing" from childhood,[17] and "devoted himself to art" from the age of ten, being one of W. Cosens Way's students at the Newcastle School of Art, where he was "one of the most successful pupils ... On one occasion he carried off the four head prizes of the year".[18][17] Macklin was selling his pictures by the age of thirteen.[19] In 1884 he moved from Newcastle to London to sketch antiques at the British Museum, and trained at Calderon's Art School until c.1887.[4][17][20] After that, he studied at John Dawson Watson's studio. In 1887 he passed the Royal Academy Schools' entrance examinations at the age of 23 years.[21] Macklin was lucky to be accepted at the Royal Academy. "He had spent three months on a special drawing to be submitted to the examiners of the Academy, but it mysteriously disappeared". There was no time to search for it, and he spent another fourteen days reproducing it, with "one hour to spare" before the entrance assessment.[17] In 1888 he won a Royal Academy silver medal for "the best copy of an oil painting".[18] Throughout his training, Macklin was "a diligent student".[18] In 1891, he was living alone at the back of King's Road, in Chelsea.[22][23]

Personal life

[edit]Macklin married Alice Martha "Alys" Philpott (d. before 1939) on 25 November 1893 at St George's, Hanover Square.[nb 5][4] They had one child, a son, born in Brittany on 4 May 1895.[24] Alys was a leading member of the Poetry Society,[25] and was a writer for the Newcastle Chronicle under the pen name Margery Lee.[26][27][28] Alys also wrote various books, including Greuze (1902),[29] and Twenty-nine Tales from the French (c.1922).[30] Following his marriage, Macklin worked in Brittany and Paris for some years, "painting pictures of peasant life",[31][32] being still there in 1895, and 1896.[13] After returning to Newcastle, Macklin and his wife Alys lived in a "little old cottage hidden in a garden behind a high stone wall in Osborne Road".[33] In 1911 the Census finds Macklin lodging at 139 Marylebone Road, NW London, and working on his own account as an artist, painter and sculptor; it says he had had one child, who was still living.[34] Alys and Thomas Eyre Macklin were separated in 1917. Alys petitioned for restitution of conjugal rights,[35] then petitioned for divorce in 1918.[36] They received their decree nisi in November 1918 on account of his abandonment, and his infidelity at the Black Rabbit Inn, Arundel, Sussex.[37]

Macklin occasionally suffered financial difficulties. In 1928 he was sued for £400 (equivalent to £30,442 in 2023), said by the plaintiff William Edward Pearson to be moneys lent and not repaid. Macklin responded that the sum was not lent, but was payment for five portraits painted. The judgement by Mr Justice Rowlatt was for the plaintiff, and Macklin had to repay £51 (equivalent to £3,881 in 2023) plus costs.[38][39][40] The Newcastle Journal commented that in Newcastle, "the local talent did not get all the commissions it deserved and London men of brush and palette pouched guineas which would materially have assisted to keep the wolf from studio doors in Pilgrim and other streets of the city ... [although] Macklin got a goodly share of Northern commissions".[41]

In 1929, Macklin had influenza and bronchitis, described as "a serious illness".[42][43] In 1939, he was a patient in hospital, but had been living in Watford. He described himself as a widower, artist and sculptor.[44] He died at "Kersbrook", Budleigh Salterton, Devon on 1 August 1943.[nb 6][4][45]

-

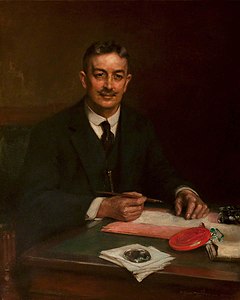

John Eyre Macklin by Thomas Eyre Macklin, 1903

-

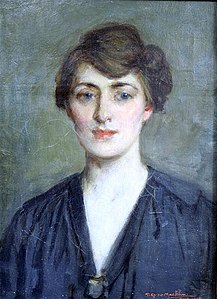

Alys Eyre Macklin, 1900 (Library of Congress)

-

Black Rabbit Inn, Sussex, 1900–1915

Career and works

[edit]Besides being an illustrator and sculptor, Macklin was a painter in oils and watercolours, and he produced landscapes, figurative pictures and portraits.[4] He also designed posters.[46] When Macklin returned from Paris he set up a studio in London.[13] He later had a studio at 22 Blackett Street, in Newcastle,[47][48] where he would sometimes exhibit his work.[49] During the 19th century, Macklin's painting style was Romantic, but one observer had other ideas about it: "His charlady noticed a skyscape hanging in his studio. 'I don't think much of that', she observed severely, 'it's too like them Turner things'".[50] In 1922, the Daily Mirror selected Macklin and two other artists to judge its beauty competition's junior section for children.[51] In 1903, the Newcastle Daily Chronicle gave the public a view of the inside of the Blackett Street studio:[52]

The portrait of Sir Charles Frederick Hamond is now complete in [Macklin's] studio ... It is a strong, characteristic portrait, some nine feet high ... In addition to the portrait, Mr Macklin, who is accomplished in modelling, has executed a bust of Sir Charles which, also, is an admirable likeness, forcible and expressive. Mr Macklin studied modelling for some years, and is reviving his interest in that branch of art. The works in his studio include a fine bust of the late Mr John Hall ... A death mask was taken, when Mr Hall died, and this has helped Mr Macklin considerably. The bust has a good pose, and is in every way excellent. In addition, Mr Macklin is busy upon a large portrait of Mr Alexander Laing which is intended to be hung in the new Laing Art Gallery.[52]

Exhibitions

[edit]Royal Academy Summer Exhibition

[edit]Macklin exhibited 17 works at the Royal Academy (RA) from 1889 when he submitted a portrait of a Lady titled From the Sunny South.[4][32][17][53] In 1900 he contributed Perros, Brittany, "a scene in Britanny, an effective piece of painting".[54][55] His portrait of Blanche was accepted for the Summer Exhibition in 1891,[23][56] and his painting of An English Girl was "hung on the line" there in 1892.[57][58][59] In 1893 his portrait of his future wife, Miss Alys Philpott, was accepted for the Summer Exhibition.[60] The Newcastle Chronicle said, "Every one who has seen Mr Macklin's work will probably conclude that it is a just tribute to his ability and perseverance. Probably the subject has inspired the artist. A portrait of a lady of considerable personal attractions certainly affords a painter a good opportunity to display his power. And it can safely be said that Mr Macklin has risen to the occasion".[28] In 1898 Macklin had three paintings on show at the RA: Ripe, Portofino, Mediterranean, and Piazza Garibaldi, Ripallo.[61] Ripe was a "skilful treatment of an orchard scene with a young woman wheeling a barrow".[62] Macklin sold its copyright for reproduction in photogravure.[63]

In 1899 it was mistakenly reported that Macklin had two portraits and two landscapes hung at the RA: Helen ("there is some vivacity in his Helen"), Mrs W.H. Dircks, A Bend of the Tees ("a simple but satisfying landscape study"), and Streatley Mill on the Thames ("a water-colour drawing with an excellent moonlit sky").[64][65] There are two versions of what happened to the four pictures. The first, testified in the Academy's catalogue, says that Macklin had three hung that year (not including Mrs Dircks), and his wife Alys had one picture on the line: Priez Pour Eux.[66] The second version, according to the Newcastle Daily Chronicle, says that there were three oil paintings and one watercolour: Streatley Mill ("managed with telling effect"), A Bend of the Tees ("not so successful" and looking "unfinished"), and portraits of a young woman in blue and a child with a bunch of flowers, both titled Helen. "Mrs A.E. Macklin, the artist's wife, is included among the addresses in the catalogue as an exhibitor, though she is not represented by any work, the explanation being that although a painting from her was accepted ... it could not be found".[67] In 1902, Macklin contributed a landscape painting of Lincoln to the Summer Exhibition.[47][68]

Other exhibitions

[edit]In February 1882, Macklin exhibited an unknown work at the Scottish Academy.[69][70] In 1892, Macklin's submission to Newcastle Art Gallery drew attention: "All that need be said with regard to Thomas Eyre Macklin's little landscape, The Heart of England – a cottage with trees and reedy pool – is that it is an exquisite gem".[71] He also exhibited at the Paris Salon, the Royal Society of British Artists and the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.[4] In February 1893, Macklin and several other Tynesider artists exhibited at the Bewick Club.[nb 7] Macklin's portrait of William Glendinning was hung "in an unfortunate position for, owing to the curious lights that play about the canvas, it [was] almost impossible to obtain a fair view of it".[72] However the Newcastle Courant saw it and declared it "too hot and purple in colour, and lacking in directness". Nevertheless that paper did approve his other work in the exhibition, a study in chalk titled Grey Eyes, which it described as "a very fine piece of work indeed".[73] In 1895 the members exhibited there again (Macklin contributed Jeannie-Yvonne),[74] and the Newcastle Chronicle's art critic, under the pen name of Merlin, said that they had "produced work that does honour to Tyneside and to the Bewick Club",[75] and that Macklin's contribution was a portrait "in which he exhibit[ed] all his usual refinement of style and decided draughtsmanship. The face is very sweet".[76] In 1903, Macklin exhibited "powerful portraits" at the Academy of Arts, Beckett Street, Newcastle.[77] In 1905 he contributed work to the Jarrow Art Exhibition, in the Engineers' Drill Hall, Western Road, Jarrow.[78] In 1908 Macklin exhibited his "dignified and fine" portrait of Edmund J. Browell, JP, alongside his black and white drawings, at the Laing Gallery, Newcastle.[79]

Illustrations

[edit]From 1888 until at least 1902, Macklin had illustrations published in various magazines including the Pall Mall Gazette.[4] In 1902, Alys and Thomas Eyre Macklin together produced A Holiday Pilgrimage: the Birthplace of Renan for Pal Mall.[80] In 1890, the Newcastle Chronicle observed cryptically that, "for some time past Mr Thomas Eyre Macklin ... has contributed high class pen and ink and other drawings to an illustrated metropolitan contemporary".[nb 8][81]

In 1893 Macklin produced "a variety of sketches" for Historical Notes on Cullercoats, Whitley and Monkseaton by William Weaver Tomlinson.[82] The Newcastle Chronicle's critic "Robin Goodfellow" reported that "the gem of these illustrations is Mr Thomas Eyre Macklin's sketch of the Whitley coast. Next come[s] the same artist's view of Monkseaton village".[83] In the same year, Wetherell's The Wide, Wide World included "six splendid reproductions of black-and-white drawings by the local artist Mr Thomas Eyre Macklin. These illustrations are of unquestionable merit, and the value of them from the painter's point of view consists in the fact that every touch of the brush reappears with all its original force".[84][85] Macklin produced the "very fine frontispiece in photogravure" for an 1893 edition of Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter,[86][87] and some illustrations for The Newcastle Christmas Annual, 1893.[88]

In 1894, Macklin contributed illustrations for Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin for the Reward Series of children's books,[89] and a frontispiece for Cradle Songs and Nursery Rhymes from the Canterbury Poets series.[90] In the same year, Macklin created frontispieces for Hawthorne's The Blithedale Romance,[91] and Our Old Home,[92] besides illustrations for Emily Grace Harding's A Noble Sacrifice.[93] In August of that year was published Denton Hall and its Association, a history of the building by William Weaver Tomlinson, which contained thirteen illustrations by Macklin.[94][nb 9] In 1895 he contributed a frontispiece in photogravure from a drawing, for Elsie Venner: a romance of destiny by Oliver Wendell Holmes.[95] In 1896, Alexandre Dumas' The Three Musketeers was published "with twelve full-page illustrations drawn by Thomas Eyre Macklin".[96] He also produced illustrations for the Monthly Chronicle of North-Country Lore and Legend.[97] In 1914, British publisher George Pulman announced: "We have published a coloured plate entitled The Angel of Peace by T. Eyre Macklin. It is a startling representation of the Kaiser's war methods".[98]

-

"Dial House, Cullercoates" for Tomlinson's Cullercoats (1893)

-

Illustration for Collins' The Woman in White, 1903

-

Illustration for Collins' The Woman in White, 1903

-

Illustration for Collins' The Woman in White, 1903

-

Capt. Paul Jones from an original drawing taken from life, on board the Serapis, undated

Landscapes and figurative paintings

[edit]While Macklin was in France, he was described by the Newcastle Daily Chronicle as "an artist of considerable reputation".[13] Macklin's The First-Born, or Le Premier Né, painted in Brittany, brought him "credit and renown".[26] It was "favourably criticised in the French papers, reproduced in two illustrated magazines, and [in 1895 it was] sold for an American gallery".[27] The above newspaper and the Newcastle Chronicle reported in 1895 and 1896:[99][100]

Since [Macklin] and his talented wife took up their residence in Brittany, Mr Macklin has been working hard. He has painted many fine pictures there, but his great production – a canvas 8 feet (2.4 m) square – has not been sent to the Royal Academy, as perhaps might have been expected, he being one of the most promising of its young men, but to the Paris Salon, where it occupies a capital position. The title of the work is The Premier Ne (sic) and shows a young mother smiling at the baby she holds in her arms as she walks homewards through a wheat field with her young husband, who, laden with scythe and rake, is pausing to light his pipe. The picture appears amongst the other great works of the year in the illustrated catalogue, and Goupil, the great Parisian art publisher, is reproducing it in gravure and colours. From all this we may infer that Mr. Macklin has now fully realised the anticipation of his many admirers.[99]

The faces of the couple are not handsome; they are probably typical of Breton faces – faces of people who, besides being toilers themselves, have descended from long generations of toilers ... the torn garments, the wooden shoes, the bronzed cheeks, and the coarse and horny hands of the father and mother, all tell a clear and almost self-evident story of hard work and many privations. The manner in which Mr Macklin has executed his masterpiece ... is almost beyond criticism. Father and mother are so naturally and exquisitely drawn, that they seem to be actually moving along ... There are life and animation in the whole performance, even in the waving corn and the distant trees.[100]

At an unknown date, Macklin painted a "large oil painting in massive gilt frame", titled The Trossachs, which was sold from Gale How, Ambleside, in 1906.[101] In 1922 Macklin went on a sketching tour of Italy.[102] In 1936, Macklin's The City Hall Floodlighted, 1935, was presented by the Belfast Telegraph to Belfast Libraries, Museums and Art Committee.[103]

-

Treguier, Brittany, 1896

-

North East Coast Landscape, 1900

-

Whittle Mill, 1904

Portrait paintings

[edit]The subjects of most of Macklin's portraits now in public collections are male civic personages, but he was also "well known for child portraits".[104] His 19th-century portraits were in the traditional style. The Newcastle Daily Chronicle said:[105]

[Macklin] clings, happily, to the older style of portrait painting – the fashion that must prevail. The desire of the newer method is to make bold portraits, in which much of the painting is apparently done with the palette knife. These have a certain striking vigour, and are effective at a distance; but they lack the softness and smoothness which characterised the best of the older portraits in this and the other countries. Mr Macklin was taught otherwise. He is a disciple of the Old Masters ... Technically the painting is superb. Mr Macklin has a wonderful command over colour; and the form stands out solidly from the background".[105]

19th-century portraits

[edit]Macklin's first portrait was of Alexander Laing, the benefactor of the Laing Art Gallery, and that was also "the first gift work the gallery possessed".[41][nb 10] He also painted the Newcastle magistrate Dr G.H. Philipson, in 1899.[48][105] Macklin painted portraits of his home town's magistrates, which were originally for the Central Courts in Pilgrim street, but at the time of his death were hanging in Newcastle Town Hall and Newcastle Art Gallery in Newcastle upon Tyne.[32] The portrait of magistrate John Hall had to be painted posthumously from a plaster cast of Hall's head and from photographs. The Newcastle Chronicle reported:[48]

There is no-one who, seeing the portrait, and ignorant of the circumstances would believe that it had been painted after death. There is a wonderful fidelity in the likeness, even in the dignified gravity which was Mr. Hall's characteristic expression. The whole picture, indeed, is characteristic of him whom it represents – gravity and dignity in the pose and aspect, and in the severe simplicity of his surroundings. Mr. Hall was, in the public eye, a plain unassuming gentleman; and Mr. Macklin's portrait conveys the same impression.[48]

One of Macklin's civic portraits was of Councillor A.P. Andersen, painted between 1898 and 1899. The Newcastle Chronicle reported: "The commission was given to that clever artist, Mr. Thomas Eyre Macklin, who has limned to perfection the mobile features of Mr. Andersen, and produced a picture of him, in his robes of office, as Sheriff of Newcastle, that will extort universal admiration".[106] In 1899 he completed a portrait of Sir Charles Hamond, of which the Newcastle Daily Chronicle said, "The likeness is perfect, both as to pose and expression".[19] Macklin executed portraits of the Kynnersley family, who lived at Leighton Hall, Shropshire. In 1891, he painted portraits of Colonel Alfred Capel-Cure of Shropshire, and of his own father John Eyre Macklin.[17]

20th-century portraits

[edit]At some point in the 20th century, Macklin began to modernise his style. in 1920, the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer said, "T. Eyre Macklin, stronger and freer in his brush work then when in bygone years he painted the portraits of so many of the Novocastrian notabilities, is well represented [at the 1920 Laing Art Gallery exhibition] by a characteristic portrait of Edwin Cleary, the war correspondent of the Daily Express".[107]

In 1900 Macklin produced a presentation portrait of the mayor of Newcastle and chief magistrate Riley Lord.[108] That portrait was donated to Newcastle Corporation in 1924, to be hung in the committee room.[109] Also in 1900, Macklin executed a portrait of Alderman R.H. Holmes, funded by Newcastle Conservative Club.[110] In 1901, Alderman Richardson's likeness was painted by Macklin, and that was hung in the magistrates' room at the City Police Court in Pilgrim Street, Newcastle.[111] In 1908, a portrait in oils and "splendidly executed work" by Macklin of C.T. Maling,[nb 11] master of the Haydon foxhounds, was presented to Maling on his retirement by his friends.[112][113] In the same year, he painted a presentation portrait for Edmund John Jasper Browell (c.1828–1914),[nb 12] who had given 50 years of unpaid civic service to County Durham.[114][115][116] In 1909 Macklin produced another presentation portrait; this time of the former mayor of Newcastle, W.J. Sanderson.[117] "The portrait [was] a very large one, and at once striking and very lifelike".[118] "The ex-Lord Mayor is depicted seated, wearing his robes of office above court dress, and the background is the lobby of the Laing Art Gallery. On a table are the accessories to municipal dignity – the mace of gold, the conical hat its bearer wears, and other accompaniments".[119]

In January 1918, a Daily Mirror journalist wrote: "The rage for photography among stage folk has not entirely killed the work of the portrait painter. Mr T. Eyre Macklin tells me that he was so impressed with the appearance of Miss Muriel Dole in a small part at His Majesty's that he determined to paint her picture".[120][nb 13] In 1921, Macklin painted a life-sized portrait of W.R. McMurray, JP, who for 50 years was the managing director of John Shaw Brown & Sons, Belfast.[121] In 1927, Macklin produced a life-sized portrait of Portadown councillor W.J. Johnston, JP, to be hung in the town hall.[122] In 1928, Macklin painted a presentation portrait of his friend Sir Robert Baird, who was the royal arch officer of the District Grand Chapter of Antrim.[123] In 1929, Macklin painted a portrait of the Grand Master of the Masonic Province of County Antrim, James H. Stirling (d.1928). The portrait was to be hung in the Masonic Hall, Arthur Square, Belfast. "Macklin had accomplished successfully a singularly difficult task, for he had only seen Br. Stirling once, and he had to paint the portrait from photographs taken from time to time".[124] In Bangor, County Down, he painted portraits of the mayor and the town clerk, Thomas S. Wilson and James Milliken.[42] In 1931, Macklin was again in Northern Ireland, painting freemason W. Bel-Burrowes.[46] The Baird and Bel-Burrowes portraits were officially presented in 1933.[125] In the same year he painted a posthumous portrait of Rev. Henry Biddall Swanzy, Dean of Dromore, for the Masonic Hall, Newry.[126] At an unknown date, Macklin painted "the group of Lord Carson signing the Ulster Covenant at the Belfast City Hall".[2]

-

Alexander Laing, 1903

-

James Hall, 1906

-

Portrait of a Young Woman, 1918

-

James Milliken, 1920–1939

-

Portrait of a Young Child, undated

Monuments and sculptures

[edit]South African War Memorial, Newcastle, 1907–1908

[edit]Macklin is perhaps best known for the South African War Memorial, previously known as the Northumberland War Memorial (sculpted in 1907; unveiled in 1908) in Percy Street, Newcastle, which is Grade II* listed.[4][127] He and Charles Septimus Errington (1869–1935) were first asked to submit plans for the monument in 1904,[128] and in 1905 it was announced that Macklin had won the competition to execute the work.[129][130] Macklin's wife Alys was the model for two of the figures on the top and at the base of the monument: Peace and Victory.[33] Standing 24m tall, it is the oldest and largest war memorial in the city,[131] memorialising "373 officers and men of Northumbrian regiments who fell in the South African War". It was unveiled by Lieutenant-general Sir Laurence Oliphant on 22 June 1908, in front of a crowd of about 30,000.[132] Afterwards, the chairman of the Executive Committee, Sir Henry Scott, spoke of "the success of [Macklin's] efforts and the artistic beauty of the result".[133] By 2016, it had become known as the "Dirty Angel" or the "Mucky Angel", and Newcastle City Council had granted planning permission to repair and refurbish the memorial.[131][134]

Bust of Alderman Sir Charles Frederick Hamond, Newcastle, 1905

[edit]Macklin created a bust of Sir Charles Frederick Hamond for Leazes Park, Newcastle, in 1905. As of 2018 the bust was still there.[135]

Land Wars Memorial, Auckland, New Zealand, 1920

[edit]Macklin's second "chief work" was the Land Wars Memorial at Auckland, New Zealand.[4][32] This memorial, in Symonds Street, is also known as the Māori War Memorial, and Zealandia War Memorial. It was designed by Macklin who won the design competition in 1914, and was unveiled on 18 August 1920. It is dedicated to "all the soldiers who had fallen during the Land Wars of the 19th century, including "the British, Australians and New Zealanders, along with the Maori allies". It has, "a draped female figure representing Zealandia offering a palm [now missing] to those who had died for the country during the Land Wars". This statue was cast in a Paris foundry.[136][nb 14]

Bangor War Memorial, County Down, 1927

[edit]Macklin's third "chief work" was the Bangor Memorial, County Down, a listed building,[137] The site, materials, and Macklin as designer, were chosen on 27 April 1925.[138] Macklin was present when the Bangor war memorial was unveiled on Empire Day, 24 May 1927, by the Duke of Abercorn, in the presence of the Bishop of Down, Connor and Dromore, a crowd "of several thousands", and much attendant ceremony.[139][140] The Herald and County Down Independent gave the following description:[141][142]

The memorial is outstandingly artistic. Its proportions are well-balanced and it is altogether at once graceful and symmetrical as viewed from the distance ... perhaps one of the prettiest settings is when it is seen from the junction of High Street and Prospect Road, using the latter as sort of vista, but pretty as it is from the distance, it loses none of its decided charm on even close approach, and, indeed on reaching the foot of the gentle knoll which it surmounts, it becomes genuinely impressive. The approach including the leading-up stepways, guards and coplings are of the very best concrete. So is the series of terraced mountings and all ramps. The pedestal plinth, oversails and cornice are, like the shaft, of beautifully-cut Portland stone laid in mathematically harmonised ashlar work, the hardness being broken at intervals by the introduction half-courses. The shaft is obelisk and carries throughout the true Egyptian ratios ending in a quadrafacial pyramid of correct proportions. The deadly dulness of the ordinary obelisk has been got rid of by the introduction of a collar of four panels showing delightful Celtic interlacing in basso relievo. On the southward face of the shaft there is shown one of the foci of the Roman lictor, with conventional additions. On the oversail on this side is a figure alleged to be of Erin holding the palm branch of victory but giving, none the less a sense of mourning – a charmingly thought-out idea. The Lion of Victory also stands out in alto relievo, and very gracefully on the opposite side is a massive bronze shield on which are graven the names of the fallen heroes whom it commemorates. On the Southern face midway up the shaft is the legend Died in the service of their country, and, on the panel of the pedestal is carved: The Great War 1914–1918. On the Northern end raised on repoussé bronze is the Latin legend Dulce et Decorum est pro Patria Mori. Altogether the War Memorial was worth waiting for and is a credit to Bangor.[141]

-

South African War Memorial, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1907

-

Detail of South African War Memorial, 1907

-

Land Wars Memorial, Auckland, 1920

-

Bangor War Memorial, County Down, 1927

Collections

[edit]Macklin has at least 20 works in various national collections, including Scolton Manor museum, Belfast Harbour Commissioners, Bangor Castle, Shipley Art Gallery, Ulster Museum, Newcastle University, South Shields Museum & Art Gallery, and the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle.[4][143] In 1892, the Central Exchange Art Gallery, or Newcastle Art Gallery, was established. Macklin had one item in its original collection: "a small but very clever portrait" titled Recollections.[144]

Institutions

[edit]In October 1900, Macklin was elected a member of the Royal Society of British Artists, being proposed by its president Wyke Bayliss.[145]

In Newcastle

[edit]Macklin was a freemason, of Delaval Lodge, Northumberland,[146] and an active member of the Archaeological and Architectural Society of Durham and Northumberland.[147] He was a founder member of the Pen and Palette Club where he would "dash off a speaking likeness of the principal guest, on the inside of an envelope".[148][149] That club was instigated on 11 November 1899 at a meeting of local artists and worthies at Macklin's studio in Blackett Street.[150] Macklin was also a member of Brunswick Cycling Club in Newcastle.[151] Politically, Macklin was an active Unionist,[152] and a member of Newcastle Liberal Club.[153]

In London

[edit]While in London, Macklin was a member of the Savage Club, together with George Loraine Stampa. When visiting the Sports Club in St James's Square, they "decorated the walls" with some comic sketches which offended some Sports Club members. However, when advised of the artist's professional standing, the members varnished the drawings and protected them with plate glass.[154]

In Northern Ireland

[edit]On 22 March 1928, a meeting of Ulster artists, attended by Macklin, "decided to form an Ulster Academy of Arts".[155] The same year, Macklin was elected chairman of the Academy, which later became the Royal Ulster Academy.[156][157] In 1931 Macklin was "chairman of the conference of painters, sculptors and architects which decided to form an academy of arts for the Province [of Northern Ireland]".[nb 15][158]

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Note: Thomas Eyre Macklin's birth was registered under the surname "Eyre", instead of Macklin: Births Jun 1863 Eyre Thomas Macklin Newcastle T (mother: Charlton) 10b 10 His death certificate also confirms that he was born around 1863. (The following birth certificate is for another child, who has different parents: Births Mar 1863 Macklin John Thomas Gateshead 10a 602)

- ^ In 1851, at the age of 18, John Eyre Macklin was a soldier in the Royal Artillery Barracks, Greenwich, but in later censuses described himself as a landscape painter.[6] He went bankrupt in 1877.[7] J.E. Macklin later recalled his exploits as a soldier in the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle and Newcastle Daily Chronicle.[8][9] As a soldier, he received a Medal of Valour from the King of Italy.[10] in 1916 he and his wife Margaret went to live with their daughter in Belfast.[11]

- ^ Note: Macklin's father Joyn Eyre Macklin is listed with surname Eyre in error, in the GRO index: Marriages Sep 1862 Eyre John Macklin, Charlton Margaret, Newcastle T 10B 222.

- ^ Margaret's birth name was possibly a variant of Burrell, e.g. Berrell, Birrel or Birrell.

- ^ Marriages Dec 1893 Philpott Alice Martha, and Macklin, Thomas Eyre, St. Geo. H. Sq. 1a 888

- ^ Deaths Sep 1943 Macklin Thomas E. 80 Devon Central 5b 29

- ^ The Bewick club was a Newcastle association of painters, including Henry Hetherington Emmerson, Ralph Hedley, John Chambers (artist), John Atlantic Stephenson and Elizabeth Cameron Mawson.

- ^ The words "illustrated" and "metropolitan" could imply a reference to the Illustrated London News or the Pall Mall Gazette.

- ^ Denton Hall (now known as Bishop's House, East Denton) still stands, in the Denton area of Newcastle.

- ^ Macklin later produced a second portrait of Laing, in 1903.

- ^ C.T. Maling was possibly a son of the potter Christopher Thompson Maling, of Maling & Sons, Newcastle.

- ^ This name was also spelled "Brewell" and "Brawell" in newspapers, but the correct spelling is "Browell". See: Deaths Jun 1914 Browell Edmund J J 86 Rothbury 10b 585. His obituary is here: "Obituary: Mr EJJ Browell", Newcastle Journal, 22 April 1914, p.4 col.6

- ^ Muriel Dole (Bristol 13 November 1886 – Kensington 1 November 1982), birth name Muriel Elsa Dole. She played Katharine in The Divine Gift (1918) a silent film. She married Frank L. Adams in 1931.

- ^ The sources given here give no indication that Macklin visited New Zealand. They do say that he provided plans for the monument, and that the bronzes for the monument were cast in Paris.

- ^ This academy was possibly the Committee for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts (CEMA), which became the Arts Council of Northern Ireland.

References

[edit]- ^ "Ulster Arts Club". Northern Whig. 3 April 1928. p. 10 col.3. Retrieved 13 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "Death of Mr T.E. Macklin". Northern Whig. 5 August 1943. p. 3 col.3. Retrieved 16 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c "1881 England Census, 43 Maple Street, Newcastle upon Tyne. RG11/5052, schedule 87, p.5". H.M. Government. 1881. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Thomas Eyre Macklin RBA Oil Portrait Of Lady 1895". antiques-atlas.com. Antiques Atlas. 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022. (includes biography of Macklin)

- ^ "John Eyre Macklin, the last of the Tyneside red-shirts". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 4 July 1907. p. 8 cols 2–3. Retrieved 13 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "1851 England Census HO/107/1858. Royal Artillery Barracks, Greenwich". ancestry.co.uk. H.M. Government. 1851. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Bankruptcies". Eastern Morning News. 17 October 1877. p. 3 col.7. Retrieved 13 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Macklin, John Eyre (4 May 1889). "Under Garibaldi, by a Newcastle volunteer: episodes and ventures with the English Legion in Italy". Newcastle Chronicle (supplement). p. 1 col.1. Retrieved 13 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Under Garibaldi ... by Lieut. John Eyre Macklin". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 26 April 1889. p. 4 col.1. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Italian medals for Newcastle Garibaldians". Shields Daily Gazette. 16 February 1867. Retrieved 13 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Mr J.E. Macklin". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 2 November 1916. p. 4 col.3. Retrieved 13 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "South African War Memorial, Newcastle, by Thomas Eyre Macklin". victorianweb.org. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Mr Thomas Eyre Macklin". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 21 November 1896. p. 4 col.4. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "1871 England Census RG10/5077 p.10. 45 Maple Street, Newcastle". ancestry.co.uk. H.M. Government. 1871. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Deaths". Northern Whig. 2 October 1924. p. 1 col.1. Retrieved 13 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ 1851 England census HO/107/2429 p.1 Warwick (village), Cumberland

- ^ a b c d e f "Literature, art, and the drama". Newcastle Chronicle. 16 May 1891. p. 8/16 col.1. Retrieved 12 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c "A Royal Academy medallist from Newcastle". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 12 December 1888. p. 5 col.2. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "Sir Charles F. Hamond MP, portrait by Mr T. Eyre Macklin". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 15 May 1899. p. 3 col.6. Retrieved 13 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Literature, art, and the drama". Newcastle Chronicle. 8 January 1887. p. 4/12 col.6. Retrieved 13 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "A local artist at the Royal Academy". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 3 January 1887. p. 5 col.2. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "1891 England census RG12/64, p.58, back of 181A Kings Road, Chelsea". ancestry.co.uk. H.M. Government. 1891. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b 1891 Exhibition Catalogue. London: Royal Academy. 1891. pp. 24, 74. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "Births". Newcastle Courant. 18 May 1895. p. 4 col.1. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Tribute to woman poet: Poetry Society's dinner to Mrs Alice Meynell". London Evening Standard. 2 June 1913. p. 8 col.5. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "Breton folks". Newcastle Chronicle. 27 June 1896. p. 4 col.3. Retrieved 11 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "It was in Merlin's column". Newcastle Chronicle. 20 July 1895. p. 4 col.5. Retrieved 11 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "Literature, art and the drama". Newcastle Chronicle. 6 May 1893. p. 8/16 col.2. Retrieved 11 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Macklin, Alys Eyre (1907). "Greuze". archive.org. T.C. & E.C. Jack, London. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ Macklin, Alys Eyre (1922). Twenty-nine Tales from the French. Harcourt, Brace and company, New York. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "The Biographer for September". Newcastle Chronicle. 15 September 1894. p. 16/8 col.1. Retrieved 11 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c d "Painter-sculptor dies". Dundee Evening Telegraph. 4 August 1943. p. 4 col.1. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "A Newcastle artist". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. 6 August 1943. p. 3 col.6. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "1911 England Census. 139 Marylebone Road, NW London". ancestry.co.uk. H.M. Government. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Divorce Court File: 834. Appellant: Alice Martha Macklin. Respondent: Thomas Eyre. Ref. J 77/1335/834". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. The National Archives. 1918. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Divorce Court File: 1602. Appellant: Alice Martha Macklin. Respondent: Thomas Eyre. Ref. J 77/1358/1602". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. National Archives. 1918. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "An artist divorced". The People. 24 November 1918. p. 5 col.6–7. Retrieved 11 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "St John's Wood painter, oil paintings in court". Marylebone Mercury. 23 June 1928. p. 8 col.4. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "St Johns Wood painter, oil paintings in court". Kensington Post. 22 June 1928. p. 8 col.4. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "One of able group". Newcastle Journal. 5 August 1943. p. 2 cols 5–6. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "Out and about". North Down Herald and County Down Independent. 23 February 1929. p. 6 col.3. Retrieved 15 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Illness of Mr T.E. Macklin, RBA". Belfast Telegraph. British Newspaper Archive. 16 February 1929. p. 9 col.3. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "1939 England and Wales Register. 36/2/75. Peace Memorial Hospital, Watford. 140-2". ancestry.co.uk. H.M. Government. 1939. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

Birth date, 30 March 1863. Residence: Watford. Patient in hospital.

- ^ "Death of Mr T.E. Macklin". Ballymena Weekly Telegraph. 6 August 1943. p. 2 col.5. Retrieved 17 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "Eminent portrait painter, return visit to Belfast". Belfast Telegraph. 24 December 1931. p. 10 col.4. Retrieved 16 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b 1902 Exhibition Catalogue. London: Royal Academy. 1902. pp. 31, 64. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d "The late Mr John Hall: portrait by Mr T. Eyre Macklin". Newcastle Chronicle. 4 November 1899. p. 8 col.7. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Mr T. Eyre Macklin". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. 15 May 1899. p. 3 col.1. Retrieved 21 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Judging the judge". Daily Mirror. 4 October 1922. p. 9 col.4. Retrieved 16 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Youthful beauties: famous artists to adjudicate in £1,000 contest. Hard work for judges". Daily Mirror. 29 September 1922. p. 2 col.2. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "Sir Chas. Hamond's portrait". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 21 March 1903. p. 3 col.3. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ 1889 Summer Exhibition. London: Royal Academy. 1889. p. 24. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ 1900 Exhibition Catalogue. London: Royal Academy. 1900. p. 28. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "The one hundered and thirty-second exhibition". Newcastle Chronicle. 12 May 1900. p. 2 col.2. Retrieved 13 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Royal Academy". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 4 May 1891. p. 8 col.2. Retrieved 11 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ 1892 Exhibition Catalogue. London: Royal Academy. 1892. p. 18. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "Success of a local artist". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. 28 April 1892. p. 4 col.2. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Amongst the local artists". Newcastle Chronicle. 30 April 1892. p. 16/8 col.2. Retrieved 11 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ 1893 Exhibition Catalogue. London: Royal Academy. 1893. p. 26. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ 1898: Exhibition Catalogue. London: Royal Academy. 1898. pp. 17, 18, 22. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ "Local pictures at the Royal Academy". Newcastle Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 7 May 1898. p. 12 col.5. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "A local artist's success". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 10 May 1898. p. 4 col.7. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The Royal Academy: third notice, northern artists". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. 12 May 1899. p. 6 col.2. Retrieved 20 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Mr T. Eyre Macklin". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. 29 April 1899. p. 3 col.5. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ 1899: Exhibition Catalogue. London: Royal Academy. 1899. pp. 22, 26, 30, 40. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "Mr T. Eyre Macklin". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 29 April 1899. p. 5 col.2. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Many things in few lines". Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette. 28 April 1902. p. 5 col.2. Retrieved 17 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Mapping of Sculpture". sculpture.gla.ac.uk. University of Glasgow. 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Local exhibitors at the Scottish Academy". Newcastle Journal. 28 February 1882. p. 3 col.3. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The Art Gallery exhibition". Newcastle Chronicle. 3 December 1892. p. 8/16 col.2. Retrieved 13 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Merlin (25 February 1893). "The Bewick Club exhibition". Newcastle Chronicle. p. 8/16 col.2. Retrieved 13 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Bewick Club exhibition: concluding article". Newcastle Courant. British Newspaper Archive. 25 February 1893. p. 5 col.7. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "The Bewick Club: annual exhibition of pictures". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 1 February 1895. p. 5 col.6. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Merlin (9 February 1895). "The Bewick Club exhibition". Newcastle Chronicle. p. 8/16 col.2. Retrieved 13 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Literature, art and the drama: the Bewick Club exhibition". Newcastle Chronicle. 23 February 1895. p. 8/16 col.1. Retrieved 22 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "North coutnry artists: exhibition at the Academy of Arts". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 26 October 1903. p. 9 col.3. Retrieved 20 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Jarrow Art Exhibition". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 30 November 1905. p. 11 col.4. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Art exhibition: northern artists in the Laing Art Gallery, Newcast.e". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. British Newspaper Archive. 15 February 1908. p. 9 col.4. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "Magazines for August". Leamington Spa Courier. 22 August 1902. p. 3 col.3. Retrieved 16 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Literature, art and the drama". Newcastle Chronicle. 23 August 1890. p. 12/4 col.5. Retrieved 11 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Literature, art and the drama". Newcastle Chronicle. 15 July 1893. p. 16 col.1. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Goodfellow, Robin (5 August 1893). "The gossip's bowl: a handsome book". Newcastle Chronicle. p. 4 col.4. Retrieved 13 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Wetherell, Elizabeth (1893). Wide, Wide World. London and Newcastle: Walter Scott Ltd.

- ^ "Literature, art and the drama". Newcastle Chronicle. 9 September 1893. p. 16/8 col.1. Retrieved 11 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Books received yesterday". Westminster Gazette. 14 December 1893. p. 7 col.2. Retrieved 16 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The Scarlet Letter". North British Daily Mail. 22 January 1894. p. 2 col.3.

- ^ "The Newcastle Christmas Annual". Newcastle Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 16 December 1893. p. 8/16 col.1. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Llenyddol &c" (In Welsh). Y Goleuad. 25 July 1894. p. 2 col.3. Retrieved 17 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The Canterbury Poets". Dorking and Leatherhead Advertiser. 20 December 1894. p. 2 col.4. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "A new issue of the works of Nathaniel Hawthorne". National Observer. 3 February 1894. p. 2 col.2. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "A new issue of the works of Nathaniel Hawthorne". National Observer. 7 July 1894. p. 4 col.1. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Reviews". Salisbury and Winchester Journal. 17 March 1894. p. 3 col.4. Retrieved 20 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Denton Hall and its Associations". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 6 August 1894. p. 5 col.3. Retrieved 22 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Publishers' announcements". Pall Mall Gazette. 26 March 1895. p. 3 col.3. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Literary gossip". Colonies and India. 19 September 1896. p. 17 col.1. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Thomas Eyre Macklin, artist, with a portrait". The Monthly Chronicle of North-Country Lore and Legend. V (LIV (August)). London and Newcastle: Walter Scott. August 1891. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Miscellaneous". Belfast News-Letter. 23 October 1914. p. 8 col.6. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "Mr Thomas Eyre Macklin". Newcastle Chronicle. 25 May 1895. p. 16/8 col.1. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "Mr Thomas Eyre Macklin". Newcastle Chronicle. 18 January 1896. p. 4 col.4. Retrieved 11 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Very short notice: Gale How, Ambleside". Lakes Chronicle and Reporter. 11 July 1906. p. 2 col.1. Retrieved 16 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "For Italy". Daily Mirror. 20 October 1922. p. 9 col.3. Retrieved 21 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Gifts to art gallery, oil paintings by Irish artists". Witness (Belfast). 24 January 1936. p. 8 col.6. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Mr T. Eyre Macklin, well known for child portraits". Daily Mirror. 10 October 1922. p. 5. Retrieved 20 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c "Portrait of Professor Philipson MD". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 24 June 1899. p. 4 col.6. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Familiar figures in Newcastle: Councillor A.P. Andersen". Newcastle Chronicle. 16 December 1899. p. 7 col.4. Retrieved 10 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Laing Gallery, Newcastle: works by north country artists". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. 31 July 1920. p. 11 col.6. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The mayor's portrait, presented to Newcastle magistrates". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. 2 January 1900. p. 3 col.2. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Portrait of Sir Riley Lord". North Star (Darlington). British Newspaper Archive. 7 March 1924. p. 5 col.1. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Mr T. Eyre Macklin RBA". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 9 November 1900. p. 4 col.4. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Zealous custodian of citezens' rights". Newcastle Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 18 January 1911. p. 5 col.5. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Testimonial to a local MFH, Mr C.T. Maling". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 7 November 1908. p. 7 col.2. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Popular MFH honoured: presentations at Fourstones to Mr C.T. Maling". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 9 November 1908. p. 7 col.6. Retrieved 20 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Fifty years' public service. Mr E.J.J. Browell honoured at South Shields". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 31 January 1908. p. 3 col.2. Retrieved 20 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Services recognised". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 27 January 1908. p. 6 col.6. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Presentation to a Durham magistrate: fifty years of public service". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. 31 January 1908. p. 8 col.5. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Court and personal". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. 28 July 1909. p. 5 col.3. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "For public services". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 28 July 1909. p. 3 col.4. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Portrait of the ex-Lord Mayor". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 11 May 1909. p. 6 col.3. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "Today's gossip: actress's portrait". Daily Mirror. 23 January 1918. p. 6 col.3. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "5 years with famous Belfast firm". Belfast Telegraph. 23 July 1921. p. 2 col.5. Retrieved 16 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Tribute to Mr Johnston". Northern Whig. 21 January 1927. p. 9 cols 3,4. Retrieved 17 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Antrim royal arch officer honoured". Belfast News-Letter. 16 October 1928. p. 10 col.2. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "A Masonic leader, the late R.W. Br. James H. Stirling. Memorial portrait unveiled". Belfast News-Letter. 12 November 1929. p. 11 cols 1,2. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Masonic ceremony: portraits unveiled". Belfast Telegraph. 16 March 1933. p. 10 col.1. Retrieved 20 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Late Dean Swanzy, unveiling of portrait". Belfast Telegraph. 14 December 1933. p. 15 col.4. Retrieved 16 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Historic England. "South African War Memorial, Haymarket (1024847)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Messrs T. Eyre Macklin and C.S. Errington". Shields Daily Gazette. 19 November 1904. p. 6 col.6. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Messrs T. Eyre Macklin and C.S. Errington". Blyth News. 22 November 1904. p. 3 col.8. Retrieved 16 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "To Northumbrian heroes: the new memorial in Barras Bridge". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 25 February 1905. p. 3 col.4. Retrieved 20 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "Newcastle's oldest and biggest war memorial to be restored to former glory". Newcastle Chronicle. 1 June 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "War Memorial at Newcastle". Lincolnshire Echo. 23 June 1908. p. 1 col.3. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Northumbria's heroes: memorial at Barras Bridge unveiled". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 23 June 1908. p. 3 cols 2–4. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Chappell, Peter (4 August 2021). "Newcastle's Mucky Angel memorial to Boer War dead to get new 'interpretation'". The Times. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ^ "Newcastle Parks: interesting functions this afternoon". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. 30 May 1905. p. 6 col.2. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Truffman, Lisa (3 July 2009). "Land Wars Memorial, Symonds Street". timespanner.blogspot.com. Timespanner. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

Lisa Truffman is a published author and authoritative New Zealand historian, serving on the executive committee of NZ History Federation.

- ^ "Bangor War Memorial Ward Park Bangor Co Down HB23/05/005, J5091 8160, 1920-1939". apps.communities-ni.gov.uk. Department for Communities. 10 August 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ "Bangor War Memorial, site in Ward Park chosen". Belfast News-Letter. 29 April 1925. p. 9 col.5. Retrieved 20 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Bangor's fallen heroes: governor unveils memorial. Plea for disabled servicement". Witness (Belfast). 27 May 1927. p. 7 col.2. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Bangor War Memorial: unveiling ceremony". Belfast News-Letter. 25 May 1927. p. 11 4–5. Retrieved 20 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "The memorial". North Down Herald and County Down Independent. 28 May 1927. p. 5 col.5. Retrieved 15 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Bangor's fallen heroes: governor unveils a dignified memorial". Northern Whig. 25 May 1927. p. 15 col.4. Retrieved 16 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Thomas Eyre Macklin". artuk.org. Art UK. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "The Newcastle Art Gallery". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 11 November 1892. p. 8 col.2. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "Mr T. Eyre Macklin". Newcastle Chronicle. 20 October 1900. p. 8 col.5. Retrieved 11 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Ulster Masonic Lodge". Northern Whig. 16 March 1932. p. 6 col.6. Retrieved 16 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "With the northern archaeologists: meeting in North Tyne". Newcastle Journal. 19 May 1893. p. 6 col.1. Retrieved 20 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Pen and Palette Club, Newcastle". The Stage. 8 March 1900. p. 17 col.2. Retrieved 17 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The Pencil Society". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 21 September 1912. p. 6 col.5. Retrieved 19 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "A Pen and Palette Club for Newcastle". Newcastle Chronicle. 18 November 1899. p. 9 col.5. Retrieved 20 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Cycling: Brunswick Cycling Club dinner". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. 23 April 1909. p. 7 col.4. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Campaign of the Unionists: vigorous address by Mr Bonar Law". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 23 September 1908. p. 10 col.5. Retrieved 20 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Peers or people? Sir R. Hudson and the menace of the Lords". Newcastle Daily Chronicle. 20 November 1909. p. 5 col.4. Retrieved 20 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "London letter". Oxfordshire Weekly News. British Newspaper Archive. 24 December 1924. p. 3 col.3. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ "An artist looks at Ulster. Antrim coast road compared with Capri". Belfast News-Letter. 23 March 1928. p. 9 col.2. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Ulster Academy of Arts". Northern Whig. 23 March 1928. p. 5 col.3. Retrieved 16 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Art in Ulster: establishing an academy". Witness (Belfast). 30 March 1928. p. 6 col.5. Retrieved 18 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Eminent portrait painter: his return visit to Belfast". Belfast Telegraph. 24 December 1931. p. 10 col.4. Retrieved 11 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

External links

[edit] Media related to Thomas Eyre Macklin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Thomas Eyre Macklin at Wikimedia Commons

- 1863 births

- 1943 deaths

- 19th-century English male artists

- 19th-century English painters

- 20th-century English male artists

- 20th-century English painters

- Artists from Newcastle upon Tyne

- English illustrators

- English landscape painters

- English male painters

- English male sculptors

- English portrait painters

- English sculptors