Third Battle of the Isonzo

| Third Battle of the Isonzo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Italian Front (World War I) | |||||||

Eleven Battles of the Isonzo June 1915 – September 1917 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

338 battalions 130 cavalry squadrons 1,250 artillery pieces |

137 + 47 battalions 604 artillery pieces. | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

67,008[1]–80,000[2] 10,733–20,000 killed 44,290–60,000 wounded 11,985 missing or captured |

41,847:[1] 8,228 killed 26,418 wounded 7,201 missing or captured | ||||||

The Third Battle of the Isonzo was fought from 18 October through 4 November 1915 between the armies of Italy and Austria-Hungary.

Background

[edit]The first move was made in Italy, on the eastern sector; because this was their third attack that year, it was named as the Third Battle of the Isonzo (as the previous two were named the First and Second Battles of the Isonzo).[3]

After roughly two and a half months of reprieve to recuperate from the casualties incurred from frontal assaults from the First and Second Battle of the Isonzo, Luigi Cadorna, Italian commander-in-chief, understood that artillery played a fundamental role on the front and brought the total number to 1,250 pieces. As well as improving artillery, the Italian Army was also issued Adrian Helmets, which proved useful in some situations but overall ineffective.[4]

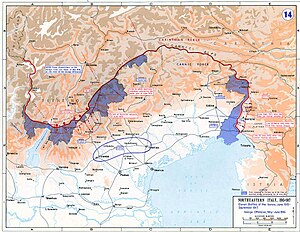

The main objectives were to take the Austro-Hungarian bridgeheads at Bovec (Plezzo in Italian), Tolmin, and (if possible) the town of Gorizia. Cadorna's tactic, of deploying his forces evenly along the entire Soča (Isonzo), proved indecisive, and the Austro-Hungarians took advantage of this by concentrating their firepower in certain areas. Specifically, the two objectives of the attack were Mount Sabotino and Mount San Michele.[3]

Location

[edit]This took place on the Austro-Hungarian side of the border between Austria-Hungary and Italy. The battle is named for the river that it was fought on (the Isonzo river), as well as the previous battles and the many that would eventually follow. Unfortunately for the Italians, it was not a prime location for attack maneuvers, since it had mountainous terrain on both sides. It also had frequently flooded banks. However, it was chosen because the Austro-Hungarian side had control of most of the other areas in the Isonzo region.[3]

Battle

[edit]Due to extensive artillery barrages, the Italians were able to advance to Plave (Plava in Italian) near Kanal ob Soči, beneath the southern end of the Banjšice Plateau (Bainsizza), and on Mount San Michele on the Karst Plateau in an attempt to outflank those forces defending Gorizia. The plateau near San Michele was the scene of heavy attacks and counterattacks involving the Italian Third Army and Austro-Hungarian reinforcements from the Eastern and Balkan fronts under the command of Svetozar Boroević; both sides suffered heavy casualties.

Thanks to the low profile held by Boroević's forces, the Austro-Hungarians were able to hold their positions despite heavy casualties, which were dwarfed by those of the Italian Army. This battle proved Boroević's tactical brilliance despite the limited scope of the front.

The lull in action lasted barely two weeks at which time the Italian offensive started anew.[5][6]

The Italians made some progress before they were eventually forced back by the Austro-Hungarians. Although the second Italian army had possession of Mt. Sabotino for a brief period of time, they were countered by the Austro-Hungarians'. The Third Army was able to approach Mt. San Michele, but were met with machine gun fire when attempting to sneak around the flank that was guarding Gorizia.[7][8] The Austro-Hungarians did not lose as many men during this, but proportionally, each side suffered similar losses.[7]

Criticism of Luigi Cadorna

[edit]Luigi Cadorna was a well-known man throughout Italy for his achievements and background; however, because of the failures the Italians suffered during World War I, Luigi Cadorna received quite a bit of negative feedback. His poor leadership skills led to many deserters during, and after the Battles of the Isonzo.[9] He assumed that the morale of Italian soldiers would win the battles at the end of the day. It was not until this Third Battle that he actually considered the sizes of troops and the amount of gunpower they possessed.[9]

Because he concentrated his attacks in very small areas, the Austro-Hungarians were able to do the same exact thing; therefore there was literally no advantage besides the fact that Cadorna had brought a few more troops in. However, because of the terrain and the area of the attack, the larger numbers also did not do the Italians much good.[8]

Aftermath

[edit]Cadorna decided to attack again a week later, starting the Fourth Battle of the Isonzo. However, it was not until the Sixth that the Italians would gain any ground and establish a presence at Gorizia.[3]

See also

[edit]- First Battle of the Isonzo - 23 June–7 July 1915

- Second Battle of the Isonzo - 18 July–3 August 1915

- Fourth Battle of the Isonzo - 10 November–2 December 1915

- Fifth Battle of the Isonzo - 9 March–17 March 1916

- Sixth Battle of the Isonzo - 6 August–17 August 1916

- Seventh Battle of the Isonzo - 14 September–17 September 1916

- Eighth Battle of the Isonzo - 10 October–12 October 1916

- Ninth Battle of the Isonzo - 1 November–4 November 1916

- Tenth Battle of the Isonzo - 12 May–8 June 1917

- Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo - 19 August–12 September 1917

- Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo - 24 October–7 November 1917 also known as the Battle of Caporetto

References

[edit]- ^ a b Schindler, John R. (2001). Isonzo: The Forgotten Sacrifice of the Great War. Praeger Publishers. p. 103/104.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gilbert, Martin (2023). The First World War: A complete History. Moscow: Квадрига. p. 283. ISBN 978-5-389-08465-0.

- ^ a b c d "Third Battle of the Isonzo". HISTORY. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- ^ "Third battle of the Isonzo, 18 October-3 November 1915". www.historyofwar.org. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- ^ FirstWorldWar.Com: The Battles of the Isonzo, 1915-17

- ^ WorldWar1.com: Isonzo 1915

- ^ a b "Third battle of the Isonzo, 18 October-3 November 1915". www.historyofwar.org. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- ^ a b Knighton, Andrew (2018-06-29). "The First Four Battles of the Isonzo: Italy Enters World War One". WAR HISTORY ONLINE. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- ^ a b "Isonzo, Battles of | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1)". encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

Further reading

[edit]- Macdonald, John, and Željko Cimprič. Caporetto and the Isonzo Campaign: The Italian Front, 1915-1918. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military, 2011. ISBN 9781848846715 OCLC 774957786

- Schindler, John R. (2001). Isonzo: The Forgotten Sacrifice of the Great War. Praeger. ISBN 0275972046. OCLC 44681903.

- Bauer, E., 1985: Der Lowe vom Isonzo, Feldmarschall Svetozar Boroević de Bojna. Aufl. Styria. Graz

- Boroević, S., 1923: O vojni proti Italiji (prevod iz nemškega jezika). Ljubljana

- Comando supremo R.E. Italiano, 1916: Addestramento della fanteria al combattimento. Roma. Tipografia del Senato

External links

[edit]- Battlefield Maps: Italian Front

- 11 battles at the Isonzo

- The Walks of Peace in the Soča Region Foundation. The Foundation preserves, restores and presents the historical and cultural heritage of the First World War in the area of the Isonzo Front for the study, tourist and educational purposes.

- The Kobarid Museum (in English) Archived 2007-11-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Društvo Soška Fronta (in Slovenian)

- Pro Hereditate - extensive site (in En/It/Sl)