Deepak Chopra

Deepak Chopra | |

|---|---|

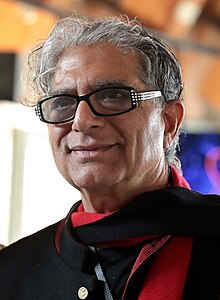

Chopra in 2019 | |

| Born | October 22, 1946[1] New Delhi, British India[2] |

| Citizenship | United States[3] |

| Alma mater | All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse |

Rita Chopra (m. 1970) |

| Children | |

| Relatives | Sanjiv Chopra (brother) |

| Website | Official website |

Deepak Chopra (/ˈdiːpɑːk ˈtʃoʊprə/; Hindi: [diːpək tʃoːpɽa]; born October 22, 1946) is an Indian-American author, new age guru,[4][5] and alternative medicine advocate.[6][7] A prominent figure in the New Age movement,[8] his books and videos have made him one of the best-known and wealthiest figures in alternative medicine.[9] In the 1990s, Chopra, a physician by education, became a popular proponent of a holistic approach to well-being that includes yoga, meditation, and nutrition, among other new-age therapies.[4][10]

Chopra studied medicine in India before emigrating in 1970 to the United States, where he completed a residency in internal medicine and a fellowship in endocrinology. As a licensed physician, in 1980, he became chief of staff at the New England Memorial Hospital (NEMH).[4] In 1985, he met Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and became involved in the Transcendental Meditation (TM) movement. Shortly thereafter, Chopra resigned from his position at NEMH to establish the Maharishi Ayurveda Health Center.[5] In 1993, Chopra gained a following after he was interviewed about his books on The Oprah Winfrey Show.[11] He then left the TM movement to become the executive director of Sharp HealthCare's Center for Mind-Body Medicine. In 1996, he cofounded the Chopra Center for Wellbeing.[4][5][10]

Chopra claims that a person may attain "perfect health", a condition "that is free from disease, that never feels pain", and "that cannot age or die".[12][13] Seeing the human body as undergirded by a "quantum mechanical body" composed not of matter but energy and information, he believes that "human aging is fluid and changeable; it can speed up, slow down, stop for a time, and even reverse itself", as determined by one's state of mind.[12][14] He claims that his practices can also treat chronic disease.[15][16]

The ideas Chopra promotes have regularly been criticized by medical and scientific professionals as pseudoscience.[17][18][19][20] The criticism has been described as ranging "from the dismissive to...damning".[17] Philosopher Robert Carroll writes that Chopra, to justify his teachings, attempts to integrate Ayurveda with quantum mechanics.[21] Chopra says that what he calls "quantum healing" cures any manner of ailments, including cancer, through effects that he claims are literally based on the same principles as quantum mechanics.[16] This has led physicists to object to his use of the term "quantum" in reference to medical conditions and the human body.[16] His discussions of quantum healing have been characterized as technobabble – "incoherent babbling strewn with scientific terms"[22] by those proficient in physics.[23][24] Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins has said that Chopra uses "quantum jargon as plausible-sounding hocus pocus".[25] Chopra's treatments generally elicit nothing but a placebo response,[9] and they have drawn criticism that the unwarranted claims made for them may raise "false hope" and lure sick people away from legitimate medical treatments.[17]

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]Chopra was born in New Delhi,[26] British India to Krishan Lal Chopra (1919–2001) and Pushpa Chopra.[27] His paternal grandfather was a sergeant in the British Indian Army. His father was a prominent cardiologist, head of the department of medicine and cardiology at New Delhi's Moolchand Khairati Ram Hospital for over 25 years, and was also a lieutenant in the British army, serving as an army doctor at the front at Burma and acting as a medical adviser to Lord Mountbatten, viceroy of India.[28] As of 2014[update], Chopra's younger brother, Sanjiv Chopra, is a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and on staff at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.[29]

Chopra completed his primary education at St. Columba's School in New Delhi and graduated from the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi in 1969. He spent his first months as a doctor working in rural India, including, he writes, six months in a village where the lights went out whenever it rained.[30] It was during his early career that he was drawn to study endocrinology, particularly neuroendocrinology, to find a biological basis for the influence of thoughts and emotions.[31]

He married in India in 1970 before emigrating, with his wife, to the United States that same year.[11] The Indian government had banned its doctors from sitting for the exam needed to practice in the United States. Consequently, Chopra had to travel to Sri Lanka to take it. After passing, he arrived in the United States to take up a clinical internship at Muhlenberg Hospital in Plainfield, New Jersey, where doctors from overseas were being recruited to replace those serving in Vietnam.[32]

Between 1971 and 1977, he completed residencies in internal medicine at the Lahey Clinic in Burlington, Massachusetts, the VA Medical Center, St Elizabeth's Medical Center, and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.[33] He earned his license to practice medicine in the state of Massachusetts in 1973, becoming board certified in internal medicine, specializing in endocrinology.[34]

East Coast years

[edit]Chopra taught at the medical schools of Tufts University, Boston University, and Harvard University,[35][36][37] and became Chief of Staff at the New England Memorial Hospital (NEMH) (later known as the Boston Regional Medical Center) in Stoneham, Massachusetts before establishing a private practice in Boston in endocrinology.[38]

While visiting New Delhi in 1981, he met the Ayurvedic physician Brihaspati Dev Triguna, head of the Indian Council for Ayurvedic Medicine, whose advice prompted him to begin investigating Ayurvedic practices.[39] Chopra was "drinking black coffee by the hour and smoking at least a pack of cigarettes a day".[40] He took up Transcendental Meditation to help him stop, and as of 2006[update], he continued to meditate for two hours every morning and half an hour in the evening.[41]

Chopra's involvement with TM led to a meeting in 1985 with the leader of the TM movement, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who asked him to establish an Ayurvedic health center.[5][42] He left his position at the NEMH. Chopra said that one of the reasons he left was his disenchantment at having to prescribe too many drugs: "[W]hen all you do is prescribe medication, you start to feel like a legalized drug pusher. That doesn't mean that all prescriptions are useless, but it is true that 80 percent of all drugs prescribed today are of optional or marginal benefit."[43]

He became the founding president of the American Association of Ayurvedic Medicine, one of the founders of Maharishi Ayur-Veda Products International, and medical director of the Maharishi Ayur-Veda Health Center in Lancaster, Massachusetts. The center charged between $2,850 and $3,950 per week for Ayurvedic cleansing rituals such as massages, enemas, and oil baths, and TM lessons cost an additional $1,000. Celebrity patients included Elizabeth Taylor.[44] Chopra also became one of the TM movement's spokespeople. In 1989, the Maharishi awarded him the title "Dhanvantari of Heaven and Earth" (Dhanvantari was the Hindu physician to the gods).[45] That year Chopra's Quantum Healing: Exploring the Frontiers of Mind/Body Medicine was published, followed by Perfect Health: The Complete Mind/Body Guide (1990).[4]

West Coast years

[edit]In June 1993, he moved to California as executive director of Sharp HealthCare's Institute for Human Potential and Mind/Body Medicine, and head of their Center for Mind/Body Medicine, a clinic in an exclusive resort in Del Mar, California, that charged $4,000 per week and included Michael Jackson's family among its clients.[46] Chopra and Jackson first met in 1988 and remained friends for 20 years. When Jackson died in 2009 after being administered prescription drugs, Chopra said he hoped it would be a call to action against the "cult of drug-pushing doctors, with their co-dependent relationships with addicted celebrities".[47][48]

Chopra left the Transcendental Meditation movement around the time he moved to California in January 1993.[49][50] Mahesh Yogi claimed that Chopra had competed for the Maharishi's position as guru,[51] although Chopra rejected this.[52] According to Robert Todd Carroll, Chopra left the TM organization when it "became too stressful" and was a "hindrance to his success".[53] Cynthia Ann Humes writes that the Maharishi was concerned, and not only with regard to Chopra, that rival systems were being taught at lower prices.[54] Chopra, for his part, was worried that his close association with the TM movement might prevent Ayurvedic medicine from being accepted as legitimate, particularly after the problems with the JAMA article.[55] He also stated that he had become uncomfortable with what seemed like a "cultish atmosphere around Maharishi".[56]

In 1995, Chopra was not licensed to practice medicine in California where he had a clinic. However, he did not see patients at this clinic "as a doctor" during this time.[57] In 2004, he received his California medical license, and as of 2014[update] is affiliated with Scripps Memorial Hospital in La Jolla, California.[58][59][60] Chopra is the owner and supervisor of the Mind-Body Medical Group within the Chopra Center, which in addition to standard medical treatment offers personalized advice about nutrition, sleep-wake cycles, and stress management based on mainstream medicine and Ayurveda.[61] He is a fellow of the American College of Physicians and member of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.[62]

Alternative medicine business

[edit]Chopra's book Ageless Body, Timeless Mind: The Quantum Alternative to Growing Old was published in 1993.[4] The book and his friendship with Michael Jackson gained him an interview on July 12 that year on Oprah. Paul Offit writes that within 24 hours Chopra had sold 137,000 copies of his book and 400,000 by the end of the week.[63] Four days after the interview, the Maharishi National Council of the Age of Enlightenment wrote to TM centers in the United States, instructing them not to promote Chopra, and his name and books were removed from the movement's literature and health centers.[64] Neuroscientist Tony Nader became the movement's new "Dhanvantari of Heaven and Earth".[65]

Sharp HealthCare changed ownership in 1996 and Chopra left to set up the Chopra Center for Wellbeing with neurologist David Simon, now located at Omni La Costa Resort & Spa in Carlsbad, California.[66] In his 2013 book, Do You Believe in Magic?, Paul Offit writes that Chopra's business grosses approximately $20 million annually, and is built on the sale of various alternative medicine products such as herbal supplements, massage oils, books, videos and courses. A year's worth of products for "anti-ageing" can cost up to $10,000, Offit wrote.[67] Chopra himself is estimated to be worth over $80 million as of 2014[update].[68] As of 2005[update], according to Srinivas Aravamudan, he was able to charge $25,000 to $30,000 per lecture five or six times a month.[69] Medical anthropologist Hans Baer said Chopra was an example of a successful entrepreneur, but that he focused too much on serving the upper-class through an alternative to medical hegemony, rather than a truly holistic approach to health.[12]

Teaching and other roles

[edit]Chopra serves as an adjunct professor in the marketing division at Columbia Business School.[70] He serves as adjunct professor of executive programs at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University.[71] He participates annually as a lecturer at the Update in Internal Medicine event sponsored by Harvard Medical School and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.[72] Robert Carroll writes of Chopra charging $25,000 per lecture, "giving spiritual advice while warning against the ill effects of materialism".[73]

In 2015, Chopra partnered with businessman Paul Tudor Jones II to found JUST Capital, a non-profit firm which ranks companies in terms of just business practices in an effort to promote economic justice.[74] In 2014, Chopra founded ISHAR (Integrative Studies Historical Archive and Repository).[75] In 2012, Chopra joined the board of advisors for tech startup State.com, creating a browsable network of structured opinions.[76] In 2009, Chopra founded the Chopra Foundation, a tax-exempt 501(c) organization that raises funds to promote and research alternative health.[77] The Foundation sponsors annual Sages and Scientists conferences.[78] He sits on the board of advisors of the National Ayurvedic Medical Association, an organization based in the United States.[79] Chopra founded the American Association for Ayurvedic Medicine (AAAM) and Maharishi AyurVeda Products International, though he later distanced himself from these organizations.[80] In 2005, Chopra was appointed as a senior scientist at The Gallup Organization.[81] Since 2004, he has been a board member of Men's Wearhouse, a men's clothing distributor.[82] In 2006, he launched Virgin Comics with his son Gotham Chopra and entrepreneur Richard Branson.[83] In 2016, Chopra was promoted from voluntary assistant clinical professor to voluntary full clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego in their Department of Family Medicine and Public Health.[84]

Personal life

[edit]Chopra and his wife have, as of 2013[update], two adult children (Gotham Chopra and Mallika Chopra) and three grandchildren.[7] As of 2019[update], Chopra lives in a "health-centric" condominium in Manhattan.[85] He is a member of the inaugural class of the Great Immigrants Award named by Carnegie Corporation of New York (July 2006)[86]

Ideas and reception

[edit]Chopra believes that a person may attain "perfect health", a condition "that is free from disease, that never feels pain", and "that cannot age or die".[12][13] Seeing the human body as being undergirded by a "quantum mechanical body" comprised not of matter but energy and information, he believes that "human aging is fluid and changeable; it can speed up, slow down, stop for a time, and even reverse itself", as determined by one's state of mind.[12][14] He claims that his practices can also treat chronic disease.[15][16]

Consciousness

[edit]Chopra speaks and writes regularly about metaphysics, including the study of consciousness and Vedanta philosophy. He is a philosophical idealist, arguing for the primacy of consciousness over matter and for teleology and intelligence in nature – that mind, or "dynamically active consciousness", is a fundamental feature of the universe.[87]

In this view, consciousness is both subject and object.[88] It is consciousness, he writes, that creates reality; we are not "physical machines that have somehow learned to think...[but] thoughts that have learned to create a physical machine".[89] He argues that the evolution of species is the evolution of consciousness seeking to express itself as multiple observers; the universe experiences itself through our brains: "We are the eyes of the universe looking at itself".[90] He has been quoted as saying: "Charles Darwin was wrong. Consciousness is key to evolution and we will soon prove that."[91] He opposes reductionist thinking in science and medicine, arguing that we can trace the physical structure of the body down to the molecular level and still have no explanation for beliefs, desires, memory and creativity.[92] In his book Quantum Healing, Chopra stated the conclusion that quantum entanglement links everything in the universe, and therefore it must create consciousness.[93] Claims of quantum consciousness are, however, disputed by scientists arguing that quantum effects have no effect in systems on the macro-level systems (i.e., the brain).[94][95]

Approach to health care

[edit]

Chopra argues that everything that happens in the mind and brain is physically represented elsewhere in the body, with mental states (thoughts, feelings, perceptions, and memories) directly influencing physiology through neurotransmitters such as dopamine, oxytocin, and serotonin. He has stated, "Your mind, your body and your consciousness – which is your spirit – and your social interactions, your personal relationships, your environment, how you deal with the environment, and your biology are all inextricably woven into a single process ... By influencing one, you influence everything."[96]

Chopra and physicians at the Chopra Center practice integrative medicine, combining the medical model of conventional Western medicine with alternative therapies such as yoga, mindfulness meditation, and Ayurveda.[97][98] According to Ayurveda, illness is caused by an imbalance in the patient's doshas, or humors, and is treated with diet, exercise, and meditative practices[99] – based on the medical evidence there is, however, nothing in Ayurvedic medicine is known to be effective at treating disease, and some preparations may be actively harmful, although meditation may be useful in promoting general well-being.[100]

In discussing health care, Chopra has used the term "quantum healing", which he defined in Quantum Healing (1989) as the "ability of one mode of consciousness (the mind) to spontaneously correct the mistakes in another mode of consciousness (the body)".[101] This attempted to wed the Maharishi's version of Ayurvedic medicine with concepts from physics, an example of what cultural historian Kenneth Zysk called "New Age Ayurveda".[102] The book introduces Chopra's view that a person's thoughts and feelings give rise to all cellular processes.[103]

Chopra coined the term quantum healing to invoke the idea of a process whereby a person's health "imbalance" is corrected by quantum mechanical means. Chopra said that quantum phenomena are responsible for health and well-being. He has attempted to integrate Ayurveda, a traditional Indian system of medicine, with quantum mechanics to justify his teachings. According to Robert Carroll, he "charges $25,000 per lecture performance, where he spouts a few platitudes and gives spiritual advice while warning against the ill effects of materialism".[21]

Chopra has equated spontaneous remission in cancer to a change in a quantum state, corresponding to a jump to "a new level of consciousness that prohibits the existence of cancer". Physics professor Robert L. Park has written that physicists "wince" at the "New Age quackery" in Chopra's cancer theories and characterizes them as a cruel fiction, since adopting them in place of effective treatment risks compounding the ill effects of the disease with guilt and might rule out the prospect of getting a genuine cure.[16]

Chopra's claims of quantum healing have attracted controversy due to what has been described as a "systematic misinterpretation" of modern physics.[104] Chopra's connections between quantum mechanics and alternative medicine are widely regarded in the scientific community as being invalid. The main criticism revolves around the fact that macroscopic objects are too large to exhibit inherently quantum properties like interference and wave function collapse. Most literature on quantum healing is almost entirely theosophical, omitting the rigorous mathematics that makes quantum electrodynamics possible.[105]

Physicists have objected to Chopra's use of terms from quantum physics. For example, he was awarded the satirical Ig Nobel Prize in physics in 1998 for "his unique interpretation of quantum physics as it applies to life, liberty, and the pursuit of economic happiness".[106][107][108] When Chopra and Jean Houston debated Sam Harris and Michael Shermer in 2010 on the question "Does God Have a Future?", Harris argued that Chopra's use of "spooky physics" merges two language games in a "completely unprincipled way".[18] Interviewed in 2007 by Richard Dawkins, Chopra said that he used the term quantum as a metaphor when discussing healing and that it had little to do with quantum theory in physics.[109][25]

Chopra wrote in 2000 that his AIDS patients were combining mainstream medicine with activities based on Ayurveda, including taking herbs, meditation, and yoga.[110] He acknowledges that AIDS is caused by the HIV virus but says that "'hearing' the virus in its vicinity, the DNA mistakes it for a friendly or compatible sound". Ayurveda uses vibrations that are said to correct this supposed sound distortion.[111] Medical professor Lawrence Schneiderman writes that Chopra's treatment has "to put it mildly...no supporting empirical data".[112]

In 2001, ABC News aired a show segment on the topic of distance healing and prayer.[113] In it, Chopra said, "There is a realm of reality that goes beyond the physical where in fact we can influence each other from a distance."[113] Chopra was shown using his claimed mental powers in an attempt to relax a person in another room, whose vital signs were recorded in charts that were said to show a correspondence between Chopra's periods of concentration and the subject's periods of relaxation.[113] After the show, a poll of its viewers found that 90% of them believed in distance healing.[114] Health and science journalist Christopher Wanjek has criticized the experiment, saying that any correspondence evident from the charts would prove nothing but that even so, freezing the frame of the video shows the correspondences are not so close as claimed. Wanjek characterized the broadcast as "an instructive example of how bad medicine is presented as exciting news" that has "a dependence on unusual or sensational science results that others in the scientific community renounce as unsound".[113]

Alternative medicine

[edit]Chopra has been described as "America's most prominent spokesman for Ayurveda".[80] His treatments benefit from the placebo response.[9] Chopra states, "The placebo effect is real medicine, because it triggers the body's healing system."[115] Physician and former U.S. Air Force flight surgeon Harriet Hall has criticized Chopra for his promotion of Ayurveda, stating, "It can be dangerous," referring to studies showing that 64% of Ayurvedic remedies sold in India are contaminated with significant amounts of heavy metals like mercury, arsenic, and cadmium and a 2015 study of users in the United States who found elevated blood lead levels in 40% of those tested.[116]

Chopra has metaphorically described the AIDS virus as emitting "a sound that lures the DNA to its destruction". The condition can be treated, according to Chopra, with "Ayurveda's primordial sound".[15] Taking issue with this view, medical professor Lawrence Schneiderman has said that ethical issues are raised when alternative medicine is not based on empirical evidence and that, "to put it mildly, Dr. Chopra proposes a treatment and prevention program for AIDS that has no supporting empirical data".[15]

He is placed by David Gorski among the "quacks", "cranks", and "purveyors of woo" and described as "arrogantly obstinate".[117] In 2013, the New York Times stated that Deepak Chopra is "the controversial New Age guru and booster of alternative medicine".[7] Time magazine stated that he is "the poet-prophet of alternative medicine".[118] He has become one of the best-known and wealthiest figures in the holistic-health movement.[9] The New York Times argued that his publishers have used his medical degree on the covers of his books as a way to promote the books and buttress their claims.[57] In 1999, Time magazine included Chopra on its list of the 20th century's heroes and icons.[119] Cosmo Landesman wrote in 2005 that Chopra was "hardly a man now, more a lucrative new age brand – the David Beckham of personal/spiritual growth".[120] For Timothy Caulfield, Chopra is an example of someone using scientific language to promote treatments that are not grounded in science: "[Chopra] legitimizes these ideas that have no scientific basis at all, and makes them sound scientific. He really is a fountain of meaningless jargon."[121] A 2008 Time magazine article by Ptolemy Tompkins commented that Chopra was a "magnet for criticism" for most of his career, and most of it was from the medical and scientific professionals.[17] Opinions ranged from the "dismissive" to the "outright damning".[17] Chopra's claims for the effectiveness of alternative medicine can, some have argued, lure sick people away from medical treatment.[17] Tompkins, however, considered Chopra a "beloved" individual whose basic messages centered on "love, health and happiness" had made him rich because of their popular appeal.[17] English professor George O'Har argues that Chopra exemplifies the need of human beings for meaning and spirit in their lives, and places what he calls Chopra's "sophistries" alongside the emotivism of Oprah Winfrey.[122] Paul Kurtz writes that Chopra's "regnant spirituality" is reinforced by postmodern criticism of the notion of objectivity in science, while Wendy Kaminer equates Chopra's views with irrational belief systems such as New Thought, Christian Science, and Scientology.[123][19]

Aging

[edit]Chopra believes that "ageing is simply learned behaviour" that can be slowed or prevented.[124] Chopra has said that he expects "to live way beyond 100".[125] He states that "by consciously using our awareness, we can influence the way we age biologically...You can tell your body not to age."[126] Conversely, Chopra also says that aging can be accelerated, for example by a person engaging in "cynical mistrust".[127] Robert Todd Carroll has characterized Chopra's promotion of lengthened life as a selling of "hope" that seems to be "a false hope based on an unscientific imagination steeped in mysticism and cheerily dispensed gibberish".[21]

Spirituality and religion

[edit]Chopra has likened the universe to a "reality sandwich" which has three layers: the "material" world, a "quantum" zone of matter and energy, and a "virtual" zone outside of time and space, which is the domain of God, and from which God can direct the other layers. Chopra has written that human beings' brains are "hardwired to know God" and that the functions of the human nervous system mirror divine experience.[128] Chopra has written that his thinking has been inspired by Jiddu Krishnamurti, a 20th-century speaker and writer on philosophical and spiritual subjects.[129]

In 2012, reviewing War of the Worldviews – a book co-authored by Chopra and Leonard Mlodinow – physics professor Mark Alford says that the work is set out as a debate between the two authors, "[covering] all the big questions: cosmology, life and evolution, the mind and brain, and God". Alford considers the two sides of the debate a false opposition and says that "the counterpoint to Chopra's speculations is not science, with its complicated structure of facts, theories, and hypotheses", but rather Occam's razor.[130]

In August 2005, Chopra wrote a series of articles on the creation–evolution controversy and Intelligent design, which were criticized by science writer Michael Shermer, founder of The Skeptics Society.[131][132][133] In 2010, Shermer said that Chopra is "the very definition of what we mean by pseudoscience".[18]

Position on skepticism

[edit]Paul Kurtz, an American skeptic and secular humanist, has written that the popularity of Chopra's views is associated with increasing anti-scientific attitudes in society, and such popularity represents an assault on the objectivity of science itself by seeking new, alternative forms of validation for ideas. Kurtz says that medical claims must always be submitted to open-minded but proper scrutiny, and that skepticism "has its work cut out for it".[134]

In 2013, Chopra published an article on what he saw as "skepticism" at work in Wikipedia, arguing that a "stubborn band of militant skeptics" were editing articles to prevent what he believes would be a fair representation of the views of such figures as Rupert Sheldrake, an author, lecturer, and researcher in parapsychology. The result, Chopra argued, was that the encyclopedia's readers were denied the opportunity to read of attempts to "expand science beyond its conventional boundaries".[135] The biologist Jerry Coyne responded, saying that it was instead Chopra who was losing out as his views were being "exposed as a lot of scientifically-sounding psychobabble".[135]

More broadly, Chopra has attacked skepticism as a whole, writing in The Huffington Post that "No skeptic, to my knowledge, ever made a major scientific discovery or advanced the welfare of others."[136] Astronomer Phil Plait said this statement trembled "on the very edge of being a blatant and gross lie", listing Carl Sagan, Richard Feynman, Stephen Jay Gould, and Edward Jenner among the "thousands of scientists [who] are skeptics", who he said were counterexamples to Chopra's statement.[137]

Misuse of scientific terminology

[edit]Reviewing Susan Jacoby's book The Age of American Unreason, Wendy Kaminer sees Chopra's popular reception in the US as symptomatic of many Americans' historical inability (as Jacoby puts it) "to distinguish between real scientists and those who peddled theories in the guise of science". Chopra's "nonsensical references to quantum physics" are placed in a lineage of American religious pseudoscience, extending back through Scientology to Christian Science.[19] Physics professor Chad Orzel has written that "to a physicist, Chopra's babble about 'energy fields' and 'congealing quantum soup' presents as utter gibberish", but that Chopra makes enough references to technical terminology to convince non-scientists that he understands physics.[138] English professor George O'Har writes that Chopra is an exemplification of the fact that human beings need "magic" in their lives, and places "the sophistries of Chopra" alongside the emotivism of Oprah Winfrey, the special effects and logic of Star Trek, and the magic of Harry Potter.[139]

Chopra has been criticized for his frequent references to the relationship of quantum mechanics to healing processes, a connection that has drawn skepticism from physicists who say it can be considered as contributing to the general confusion in the popular press regarding quantum measurement, decoherence and the Heisenberg uncertainty principle.[107] In 1998, Chopra was awarded the satirical Ig Nobel Prize in physics for "his unique interpretation of quantum physics as it applies to life, liberty, and the pursuit of economic happiness".[140] When interviewed by ethologist and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in the Channel 4 (UK) documentary The Enemies of Reason, Chopra said that he used the term "quantum physics" as "a metaphor" and that it had little to do with quantum theory in physics.[141] In March 2010, Chopra and Jean Houston debated Sam Harris and Michael Shermer at the California Institute of Technology on the question "Does God Have a Future?" Shermer and Harris criticized Chopra's use of scientific terminology to expound unrelated spiritual concepts.[18] A 2015 paper examining "the reception and detection of pseudo-profound bullshit" used Chopra's Twitter feed as the canonical example, and compared this with fake Chopra quotes generated by a spoof website.[20][142][143]

Yoga

[edit]In April 2010, Aseem Shukla, co-founder of the Hindu American Foundation, criticized Chopra for suggesting that yoga did not have its origins in Hinduism but in an older Indian spiritual tradition.[144] Chopra later said that yoga was rooted in "consciousness alone" expounded by Vedic rishis long before historic Hinduism ever arose. He said that Shukla had a "fundamentalist agenda". Shukla responded by saying Chopra was an exponent of the art of "How to Deconstruct, Repackage and Sell Hindu Philosophy Without Calling it Hindu!", and he said Chopra's mentioning of fundamentalism was an attempt to divert the debate.[144][145]

Legal actions

[edit]In May 1991, the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) published an article by Chopra and two others on Ayurvedic medicine and TM.[146] JAMA subsequently published an erratum stating that the lead author, Hari M. Sharma, had undisclosed financial interests, followed by an article by JAMA associate editor Andrew A. Skolnick which was highly critical of Chopra and the other authors for failing to disclose their financial connections to the article subject.[147] Several experts on meditation and traditional Indian medicine criticized JAMA for accepting the "shoddy science" of the original article.[148] Chopra and two TM groups sued Skolnick and JAMA for defamation, asking for $194 million in damages, but the case was dismissed in March 1993.[149]

After Chopra published his book, Ageless Body, Timeless Mind (1993), he was sued for copyright infringement by Robert Sapolsky for having used, without proper attribution, "five passages of text and one table" displaying information on the endocrinology of stress.[150] An out-of-court settlement resulted in Chopra correctly attributing material that was researched by Sapolsky.[151]

Select bibliography

[edit]According to publishers HarperCollins, Chopra has written more than 80 books which have been translated into more than 43 languages, including numerous New York Times bestsellers in both fiction and nonfiction categories.[152] His book The Seven Spiritual Laws of Success was on The New York Times Best Seller list[153] for 72 weeks.[154]

Books

- Creating Health. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 1987. ISBN 978-0-395-42953-2.

- Quantum Healing. New York: Bantam Books. 1989. ISBN 978-0-553-05368-5.

- Perfect Health. New York: Harmony Books. 1990. ISBN 0517571951.

- Return of the Rishi: A Doctor's Story of Spiritual Transformation and Ayurvedic Healing. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 1991. ISBN 978-0-395-57420-1.

- Ageless Body Timeless Mind. New York: Harmony Books. 1993. ISBN 978-0-517-59257-1.

- The Seven Spiritual Laws of Success. San Rafael: Amber Allen Publishing and New World Library. 1994. ISBN 978-1-878424-11-2.

- The Return of Merlin. New York: Harmony Books. 1995. ISBN 978-0-517-59849-8.

- The Way of the Wizard. New York: Random House. 1995. ISBN 978-0-517-70434-9.

- The Path to Love. New York: Harmony Books. 1997. ISBN 978-0-517-70622-0.

- with Simon, David (2000). The Chopra Center Herbal Handbook. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-609-80390-5.

- The Book of Secrets. New York: Harmony. 2004. ISBN 978-0-517-70624-4.

- The Third Jesus. New York: Harmony Books. 2008. ISBN 978-0-307-33831-0.

- Reinventing the Body, Resurrecting the Soul. New York: Harmony Books. 2009. ISBN 978-0-307-45233-7.

- The Soul of Leadership. New York: Harmony Books. 2010. ISBN 978-0-307-40806-8.

- with Mlodinow, Leonard (2011). War of the Worldviews. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-307-88688-0.

- with Chopra, Gotham (May 31, 2011). The Seven Spiritual Laws of Superheroes: Harnessing Our Power to Change the World. HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-205966-6.

- God: A Story of Revelation. New York: HarperOne. October 8, 2013. ISBN 978-0-06-202069-7.

- with Tanzi, Rudolph E. (2012). Super Brain. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-307-95682-8.

- with Chopra, Sanjiv (2013). Brotherhood: Dharma, Destiny, and the American Dream. New York: New Harvest. ISBN 978-0-544-03210-1.

- What Are You Hungry For?. New York: Harmony Books. 2013. ISBN 978-0-7704-3721-3.

- with Tanzi, Rudolph E. (2015). Super Genes. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-8041-4013-3.

- with Kafatos, Menas (2017). You Are the Universe. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0307889164.

- Metahuman. New York: Harmony. 2019. ISBN 978-0307338334.

- Total Meditation. Harmony. 2020. ISBN 9781984825315.

- with Tanzi, Rudolph E. (2020). The Healing Self. Harmony. ISBN 9780451495549.

- with Platt-Finger, Sarah (2023). Living in the Light: Yoga for Self-Realization. Random House. ISBN 9780593235423.

See also

[edit]- Celebrity doctor

- Hard problem of consciousness

- Indian Americans

- Indians in the New York City metropolitan area

- List of people in alternative medicine

- Panpsychism

- Spiritual naturalism

References

[edit]- ^ Chopra & Chopra 2013, pp. 5ff.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Britannica Almanac 2010. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2010. p. 42. ISBN 978-1615353293.

- ^ Jeffrey Brown (May 13, 2013). "Chopra Brothers Tell Story of How They Became Americans and Doctors in Memoir". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

Chopra & Chopra 2013, p. 194

Boye Lafayette De Mente (1976). Cultural Failures That Are Destroying the American Dream! – The Destructive Influence of Male Dominance & Religious Dogma!. Cultural-Insight Books. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-914778-17-2. - ^ a b c d e f Perry, Tony (September 7, 1997). "So Rich, So Restless". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Baer 2003, p. 237

- ^ "Deepak Chopra". The Huffington Post. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ a b c Chopra 1991, pp. 54–57[incomplete short citation]; Joanne Kaufman, "Deepak Chopra – An 'Inner Stillness,' Even on the Subway", The New York Times, October 17, 2013.

- ^ Alter, Charlotte (November 26, 2014). "Deepak Chopra on Why Gratitude is Good For You". Time. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Gamel, John W. (2008). "Hokum on the Rise: The 70-Percent Solution". The Antioch Review. 66 (1): 130. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2023.

It seems appropriate that Chopra and legions of his ilk should now populate the halls of academic medicine, since they carry on the placebo-dominated traditions long ago established in those very halls by their progenitors

- ^ a b David Steele (2012). The Million Dollar Private Practice: Using Your Expertise to Build a Business That Makes a Difference. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-1-118-22081-8.

- ^ a b Dunkel, Tom (2005). "Inner Peacekeeper". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Baer, Hans A. (June 2003). "The work of Andrew Weil and Deepak Chopra—two holistic health/New Age gurus: a critique of the holistic health/New Age movements". Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 17 (2): 240–241. doi:10.1525/maq.2003.17.2.233. JSTOR 3655336. PMID 12846118. S2CID 28219719.

- ^ a b Chopra, Deepak (December 2007). Perfect Health—Revised and Updated: The Complete Mind Body Guide. New York City: Three Rivers Press. p. 7. ISBN 9780307421432.

- ^ a b Chopra, Deepak (1997). Ageless Body, Timeless Mind: The Quantum Alternative to Growing Old. Random House. p. 6. ISBN 9780679774495.

- ^ a b c d Schneiderman, LJ (2003). "The (alternative) medicalization of life". Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 31 (2): 191–7. doi:10.1111/j.1748-720X.2003.tb00080.x. PMID 12964263. S2CID 43786245.

- ^ a b c d e Park, Robert L. (2005). "Chapter 9: Voodoo medicine in a scientific world". In Ashman, Keith; Barringer, Phillip (eds.). After the Science Wars: Science and the Study of Science. Routledge. pp. 137–. ISBN 978-1-134-61618-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tompkins, Ptolemy (November 14, 2008). "New Age Supersage". Time. Archived from the original on April 12, 2009.

Ever since his early days as an advocate of alternative healing and nutrition, Chopra has been a magnet for criticism—most of it from the medical and scientific communities. Accusations have ranged from the dismissive—Chopra is just another huckster purveying watered-down Eastern wisdom mixed with pseudo science and pop psychology—to the outright damning.

- ^ a b c d "Face-Off: Does God Have a Future". Nightline. Season 30. Episode 58. March 23, 2010. ABC. Transcript from the Internet Archive. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c Wendy Kaminer (Spring 2008). "The Corrosion of the American Mind". The Wilson Quarterly. 32 (2): 92 (91–94). JSTOR 40262377.

Then came Scientology, the 'science' of positive thinking, and, more recently, New Age healer Deepak Chopra's nonsensical references to quantum physics.

Text at Wilson Quarterly - ^ a b "Scientists find a link between low intelligence and acceptance of 'pseudo-profound bulls***'". The Independent. December 4, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c Carroll, Robert Todd (May 19, 2013), "Deepak Chopra", The Skeptic's Dictionary

- ^ Strauss, Valerie (May 15, 2015). "Scientist: Why Deepak Chopra is driving me crazy". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ Plait, Phil (December 1, 2009). "Deepak Chopra: redefining "wrong"". Slate. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ Burkeman, Oliver (November 23, 2012). "This column will change your life: pseudoscience". Retrieved May 19, 2018.

[Chopra]'s the guy behind Ask The Kabala and 'quantum healing', which involves 'healing the bodymind from a quantum level' by a 'shift in the fields of energy information', and which drives people who actually understand physics crazy; his critics accuse him of selling false hope to the sick.

- ^ a b Chopra, Deepak (June 19, 2013). "Richard Dawkins Plays God: The Video (Updated)". The Huffington Post. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Chamberlain, Adrian (October 10, 2015). "Backstage: A lesson in concentration from Deepak Chopra". Times Colonist.

- ^ Chopra & Chopra 2013, pp. 5, 161.

- ^ Chopra 2013, pp. 5–6, 11–13; Michael Schulder (May 24, 2013). "The Chopra Brothers". CNN. Archived from the original on June 28, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- ^ "Chopra, Sanjiv, MD" Archived December 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ Deepak Chopra, Return of the Rishi, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1991, p. 1.

- ^ Carl Lindgren (March 31, 2010). "International Dreamer – Deepak Chopra". Map Magazine's Street Editors. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011.

- ^ Chopra 1991, p. 57[incomplete short citation]; Deepak Chopra, "Special Keynote with Dr. Deepak Chopra", November 2013, from 2:50 mins; Richard Knox, "Foreign doctors: a US dilemma", The Boston Globe, June 30, 1974.

- ^ "Dr. Deepak K Chopra" Archived May 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, U.S. News & World Report.

- ^ "Deepak K. Chopra, M.D." Archived May 21, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Commonwealth of Massachusetts Board of Registration in Medicine; "Verify a Physician's Certification" Archived December 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, American Board of Internal Medicine.

- ^ Lambert, Craig A. (July 1989). "Quantum Healing: An Interview with Deepak Chopra, M.D." Yoga Journal (87): 47–53.

- ^ Young, Anna M. (2014). Prophets, Gurus, and Pundits: Rhetorical Styles and Public Engagement. SIU Press. pp. 59–68. ISBN 978-0809332953. OCLC 871781118.

- ^ Hill, Maria (2016). The Emerging Sensitive: A Guide for Finding Your Place in the World. BookBaby. ISBN 978-1682224755. OCLC 953493840.

- ^ Baer, Hans A. (2004). Toward an Integrative Medicine. Rowman Altamira. p. 121. ISBN 978-0759103023. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ Chopra 1991, p. 105ff.[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Chopra 1991, p. 125.[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Rosamund Burton (June 4, 2006). "Peace Seeker". Nova Magazine. Archived from the original on November 5, 2013.

- ^ Chopra 1991, p. 139ff[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Nafeez Mosaddeq Ahmed, "The Crisis of Perception", Media Monitors Network, February 29, 2008.

- ^ Pettus, Elise (August 14, 1995). "The Mind–Body Problems". New York. pp. 28–31, 95, 30. Also see Deepak Chopra, "Letters: Deepak responds", New York, September 25, 1995, p. 16.

- ^ Humes, Cynthia Ann (2009). "Schisms within Hindu guru groups: the Transcendental Meditation movement in North America". In James R. Lewis; Sarah M. Lewis (eds.). Sacred Schisms: How Religions Divide. Cambridge University Press. p. 297.. Also see Humes, Cynthia Ann (2005). "Maharishi Mahesh Yogi: Beyond the TM Technique". In Thomas A. Forsthoefel; Cynthia Ann Humes (eds.). Gurus in America. State University of New York Press. pp. 68–69.

- ^ Pettus 1995, p. 31

- ^ "A Tribute to My Friend, Michael Jackson" by Deepak Chopra, The Huffington Post, June 26, 2009

- ^ Gerald Posner, "Deepak Chopra: How Michael Jackson Could Have Been Saved", The Daily Beast, July 2, 2009, p. 4.

- ^ Pettus 1995, p. 31.

- ^ Baer 2004, p. 129.

- ^ Deepak Chopra, "The Maharishi Years – The Untold Story: Recollections of a Former Disciple", The Huffington Post, February 13, 2008.

- ^ Nilanjana Bhaduri Jha (June 22, 2004). "'Employee loyalty comes first, the rest will follow' – Economic Times". The Times of India. Archived from the original on June 7, 2014. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ^ Carroll, Robert Todd (2011). The Skeptic's Dictionary: A Collection of Strange Beliefs, Amusing Deceptions, and Dangerous Delusions. John Wiley & Sons. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-118-04563-3.

- ^ Humes 2005, p. 69; Humes 2009, pp. 299, 302

- ^ Humes, Cynthia Ann (2008). "Maharishi Ayur-Veda: Perfect Health through Enlightened Marketing in America". In Frederick M. Smith; Dagmar Wujastyk (eds.). Modern and Global Ayurveda: Pluralism and Paradigms. State University of New York Press. p. 324.

- ^ Hoffman, Claire (February 22, 2013). "David Lynch Is Back ... as a Guru of Transcendental Meditation". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Elise Pettus (August 14, 1995). "The Mind–Body Problems". New York. pp. 95ff. Retrieved December 16, 2014 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Chopra, Deepak" Archived May 21, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, California Department of Consumer Affairs. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Dr. Deepak K Chopra" Archived May 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Endocrinologists, Scripps La Jolla Hospitals and Clinics", U.S. News & World Report. Archived May 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Mind–Body Medical Group" Archived May 29, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Chopra Center; Deepak Chopra, "The Mind–Body Medical Group at the Chopra Center", The Chopra Well, May 26, 2014.

- ^ "Deepak Chopra, M.D." Archived May 15, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, The Chopra Center.

- ^ Paul A. Offit, Do You Believe in Magic? The Sense and Nonsense of Alternative Medicine, HarperCollins, 2013, p. 39; "Full Transcript: Your Call with Dr Deepak Chopra" Archived May 21, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, NDTV, January 23, 2012; also see Craig Bromberg, "Doc of Ages", People, November 15, 1993.

- ^ For the National Council's letter, Humes 2005, p. 68; Humes 2009, p. 297; for the rest, Pettus 1995, p. 31

- ^ Humes 2008, p. 326.

- ^ David Ogul (February 9, 2012). "David Simon, 61, mind-body medicine pioneer, opened Chopra Center for Wellbeing". U-T San Diego. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 20, 2014.

- ^ Offit, Paul (2013). Do You Believe in Magic? The Sense and Nonsense of Alternative Medicine. HarperCollins. pp. 245–246. ISBN 978-0-06-222296-1.

- ^ Rowe 2014, Truly, madly, deeply Deepak Chopra.

- ^ Srinivas Aravamudan, Guru English: South Asian Religion in a Cosmopolitan Language, Princeton University Press, 2005, p. 257.

- ^ "Deepak Chopra". Columbia Business School, Columbia University in the City of New York. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ "Deepak Chopra – Faculty". Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University. Archived from the original on March 26, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ^ "Update in Internal Medicine". updateinternalmedicine.com/faculty. updateinternalmedicine.com. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ Robert Todd Carroll (2011). "Auyrvedic medicine". The Skeptic's Dictionary. John Wiley & Sons. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-118-04563-3.

- ^ Stanley, Alessandra (December 20, 2015). "A Plan to Rank 'Just' Companies Aims to Close the Wealth Gap". The New York Times. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ Maureen Seaberg. "Let's Raise ISHAR!". The Huffington Post. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ "State.com/about". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved September 9, 2013.

- ^ Jane Kelly (October 9, 2013). "Chopra and Huffington to Hold a Public Meditation on the Lawn Oct. 15". UVAToday.

- ^ Anne Cukier (January 22, 2014). "Sages and Scientists Symposium 2014". Zapaday.

- ^ "NAMA's Board of Advisors".

- ^ a b Butler, J. Thomas (2011). Consumer Health: Making Informed Decisions. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-1-4496-7543-1.

- ^ "Gallup Senior Scientists". Gallup.com. Archived from the original on February 16, 2011. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ^ Belton, Beth (June 25, 2013). "Men's Wearhouse fires back at George Zimmer". USA Today. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ^ David Segal, "Deepak Chopra And a New Age Of Comic Books", The Washington Post, March 3, 2007.

- ^ Robbins, Gary (March 15, 2016). "UCSD deepens ties with Deepak Chopra". U-T San Diego.

- ^ Jordi Lippe-Mcgraw (July 16, 2019). "Live Like Leonardo DiCaprio and Deepak Chopra in this Wellness-Focused Manhattan Building". Architectural Digest. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ "2006 Great Immigrants: Deepak Chopra". Carnegie Corporation of New York. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ Deepak Chopra, "What Is Consciousness & Where Is It?", discussion with Rudolph Tanzi, Menas Kafatos and Lothar Schäfer, Science and Nonduality Conference, 2013, 08:12 mins.

- Attila Grandpierre, Deepak Chopra, P. Murali Doraiswamy, Rudolph Tanzi, Menas C. Kafatos, "A Multidisciplinary Approach to Mind and Consciousness", NeuroQuantology, 11(4), December 2013 (pp. 607–617), p. 609.

- ^ Deepak Chopra, Stuart Hameroff, "The 'Quantum Soul': A Scientific Hypothesis", in Alexander Moreira-Almeida, Franklin Santana Santos (eds.), Exploring Frontiers of the Mind-Brain Relationship, Springer, 2011 (pp. 79–93), p. 85.

- ^ Chopra, Deepak (2009) [1989]. Quantum Healing: Exploring the Frontiers of Mind Body Medicine. Random House. pp. 71–72, 74. ISBN 9780307569950.

- ^ Deepak Chopra, "Dangerous Ideas: Deepak Chopra & Richard Dawkins", Archived May 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine University of Puebla, November 9, 2013, 26:23 mins.

- Also see Deepak Chopra, Menas Kafatos, Rudolph E. Tanzi, "From Quanta to Qualia: The Mystery of Reality (Part 1)", "(Part 2)", "(Part 3)", "(Part 4)", The Huffington Post, October 8, 15, 29 and November 12, 2012.

- ^ "India Today Conclave 2015: Darwin was wrong, says Deepak Chopra". India Today. March 13, 2015.

As quoted by Steve Newton (April 8, 2015). "Why Does Deepak Chopra Hate Me?". NCSE blog.

As quoted by Valerie Strauss (May 20, 2015). "Deepak Chopra blasts scientist who criticized his view of evolution. The scientist fires back". The Washington Post (blog). - ^ Deepak Chopra and Leonard Mlodinow, War of the Worldviews, Random House, 2011, p. 123.

- ^ O'Neill, Ian (May 26, 2011). "Does Quantum Theory Explain Consciousness?". Discovery News. Discovery Communications, LLC. Archived from the original on August 13, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ Stenger, Victor (1995). The Unconscious Quantum. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-022-3.

- ^ Shermer, Michael (2011). The Believing Brain: From Ghosts and Gods to Politics and Conspiracies – How We Construct Beliefs and Reinforce Them as Truths. Macmillan. pp. 177–178. ISBN 978-0-8050-9125-0.

- ^ Deepak Chopra, "Deepak Chopra Meditation", YouTube, December 10, 2012.

- ^ "Deepak Chopra and the Chopra Center". ReligionFacts.com. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ "Oprah Winfrey & Deepak Chopra Launch All-New Meditation Experience 'Expanding Your Happiness'". Broadway World. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ For imbalance, see Baer 2004, p. 128; for the rest, Chopra 2009 [1989], pp. 222–224, 234ff.

- ^ "Ayurvedic medicine". Cancer Research UK. August 30, 2017.

There is no scientific evidence to prove that Ayurvedic medicine can treat or cure cancer or any other disease.

- ^ Chopra 2009 [1989], pp. 15, 241; Deepak Chopra, "Healing wisdom" Archived May 21, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, The Chopra Center, June 12, 2013.

- That he uses the term "quantum healing" as a metaphor, see Richard Dawkins, "Interview with Chopra", The Enemies of Reason, Channel 4 (UK) Archived January 8, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, 2007, 01:16 mins.

- ^ Suzanne Newcombe, "Ayurvedic Medicine in Britain and the Epistemology of Practicing Medicine in Good Faith", in Smith and Wujastyk 2008, pp. 263–264; Kenneth Zysk, "New Age Ayurveda or what happens to Indian medicine when it comes to America", Traditional South Asian Medicine, 6, 2001, pp. 10–26. Also see Francoise Jeannotat, "Maharishi Ayur-veda", in Smith and Wujastyk 2008, p. 285ff.

- ^ Zamarra, John W. (1989). "Book Review Quantum Healing: Exploring the frontiers of mind/body medicine". New England Journal of Medicine. 321 (24): 1688. doi:10.1056/NEJM198912143212426.

- ^ Cox, Brian (February 20, 2012). "Why Quantum Theory Is So Misunderstood – Speakeasy". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ "'Magic' of Quantum Physics". Aske-skeptics.org.uk. Archived from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ Park 2005, p. 137.

- ^ a b Victor J. Stenger (2007). "Quantum Quackery". Skeptical Inquirer. 27 (1): 37. Bibcode:2005SciAm.292a..34S. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0105-34.

- ^ "Winners of the Ig Nobel Prize". Improbable Research. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- Brian Cox says that "for some scientists, the unfortunate distortion and misappropriation of scientific ideas that often accompanies their integration into popular culture is an unacceptable price to pay". See Cox 2012

- The main criticism revolves around the fact that macroscopic objects are too large to exhibit inherently quantum properties like interference and wave function collapse. Most literature on quantum healing is almost entirely theosophical, omitting the rigorous mathematics that makes quantum electrodynamics possible. See Doug Bramwell. "'Magic' of Quantum Physics". Association for Skeptical Enquiry. Archived from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ Richard Dawkins, "Interview with Chopra", Archived May 9, 2014, at the Wayback Machine The Enemies of Reason, Channel 4 (UK). "The Enemies of Reason - All 4". Archived from the original on January 8, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2013., 2007

- ^ Dann Dulin, "The Medicine Man", interview with Deepak Chopra, A&U magazine, 2000.

- ^ Chopra 2009 [1989], pp. 37, 237, 239–241.

- ^ Lawrence J. Schneiderman (2003). "The (Alternative) Medicalization of Life". Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 31 (2): 191–7. doi:10.1111/j.1748-720X.2003.tb00080.x. PMID 12964263. S2CID 43786245.

- ^ a b c d Wanjek, Christopher (2003). Bad Medicine: Misconceptions and Misuses Revealed, from Distance Healing to Vitamin O. Wiley Bad Science Series. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 224–. ISBN 978-0-471-46315-3. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ Posner, Gary P (2001). "Hardly a Prayer on ABC's 20/20 Downtown". Skeptical Inquirer. 25 (6): 9. Archived from the original on November 6, 2023.

- ^ Deepak, Deepak (October 17, 2012). "I Will Not Be Pleased – Your Health and the Nocebo Effect". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Hall, Harriet (December 14, 2017). "Ayurveda: Ancient Superstition, Not Ancient Wisdom". Skeptical Inquirer. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ David Gorski. "Deepak Chopra tries his hand at a clinical trial. Woo ensues". Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ Dare, Stephen (March 15, 2016). "Stephen Dare Interviews Deepak Chopra". Metro Jacksonville.

- ^ For Time, Peter Rowe, "Truly, madly, deeply Deepak Chopra", U-T San Diego, May 3, 2014, p. 1 Archived May 27, 2014, at archive.today

- ^ Landesman, Cosmo (May 8, 2005). "There's an easy way to save the world". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved November 10, 2017. (subscription required)

- ^ "Deepak Chopra, Timothy Caulfield end Twitter feud". CBC News. January 26, 2017. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ George M. O'Har (2000). "Magic in the Machine Age". Technology and Culture. 41 (4): 864. doi:10.1353/tech.2000.0174. JSTOR 25147641. S2CID 110355126.

- ^ Paul Kurtz, Skepticism and Humanism: The New Paradigm, Transaction Publishers, 2001, p. 110

- ^ Henderson, Mark (February 7, 2004). "Junk medicine; The triumph of mumbo jumbo". The Times (Book review). p. 4.

- ^ Francis Wheen (2005). How Mumbo-Jumbo Conquered the World: A Short History of Modern Delusions. PublicAffairs. pp. 46–. ISBN 978-0-7867-2352-2.

- ^ Schwarcz, Joe (2009) Science, Sense & Nonsense, Doubleday Canada. ISBN 978-0307374646. p153.

- ^ Moukheiber, Zina (1994). "Lord of immortality". Forbes (Book review). 153 (8): 132.

- ^ Lois Malcolm (2003). "God as best seller: Deepak Chopra, Neal Walsch and New Age theology". The Christian Century. 120 (19): 31. commenting on Deepak Chopra (2008). How To Know God. Ebury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4090-2220-6.

- ^ Blau, Evelyne (1995). Krishnamurti: 100 Years. Stewart, Tabori, & Chang. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-55670-407-9.

- ^ Alford, Mark (2012). "Is science the antidote to Deepak Chopra's spirituality?". Skeptical Inquirer. 36 (3): 54. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012.

- ^ Chopra, Deepak (August 23, 2005). "Intelligent Design Without the Bible". The Huffington Post. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ Shermer, Michael (March 28, 2008). "Skyhooks and Cranes: Deepak Chopra, George W. Bush, and Intelligent Design". The Huffington Post. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ^ Chopra, Deepak (August 24, 2005). "Rescuing Intelligent Design – But from Whom?". The Huffington Post. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ Paul Kurtz (2001). Skepticism and Humanism: The New Paradigm. Transaction Publishers. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-4128-3411-7. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ a b Coyne, Jerry A (November 8, 2013). "Pseudoscientist Rupert Sheldrake Is Not Being Persecuted, And Is Not Like Galileo". The New Republic.

- ^ Chopra, Deepak (November 30, 2009). "The Perils of Skepticism". The Huffington Post. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ Plait, Phil (December 1, 2009). "Deepak Chopra: redefining 'wrong'". Discover. Archived from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ Orzel, Chad (October 11, 2013). "Malcolm Gladwell Is Deepak Chopra". ScienceBlogs. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ O'Har, George M (2000). "Magic in the Machine Age". Technology and Culture. 41 (4): 862–864. doi:10.1353/tech.2000.0174. S2CID 110355126.

- ^ "Winners of the Ig Nobel Prize". Improbable Research. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- ^ "The Enemies of Reason". Channel 4. Archived from the original on January 8, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ "Study Finds People Who Fall For Nonsense Inspirational Quotes Are Less Intelligent". The Huffington Post. December 4, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ Pennycook, Gordon; et al. (November 2015). "On the reception and detection of pseudo-profound bullshit". Judgment and Decision Making. 10 (6). Pennsylvania: Society for Judgment and Decision Making (SJDM) and the European Association for Decision Making (EADM): 549–563. doi:10.1017/S1930297500006999. S2CID 16505606. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ^ a b Shukla, Aseem (April 28, 2010). "Dr. Chopra: Honor thy heritage". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 30, 2010. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ^ Shukla, Aseem. "On Faith Panelists Blog: Hinduism and Sanatana Dharma: One and the same". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 3, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ Hari M. Sharma; B. D. Triguna; Deepak Chopra (May 22, 1991). "Maharishi Ayur-Veda: Modern insights into ancient medicine". Journal of the American Medical Association. 265 (20): 2633–4, 2637. doi:10.1001/jama.265.20.2633. PMID 1817464.

- ^ "Financial Disclosure". JAMA. 266 (6): 798. August 14, 1991. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03470060060025.; Andrew A. Skolnick (October 2, 1991). "Maharishi Ayur-Veda: Guru's marketing scheme promises the world eternal 'perfect health'". JAMA. 266 (13): 1741–1750. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03470130017003. PMID 1817475. Archived from the original on May 25, 2013. Retrieved August 10, 2013..

- Also see Andrew A. Skolnick (Fall 1991). "The Maharhish Caper: Or How to Hoodwink Top Medical Journals". ScienceWriters. Archived from the original on July 16, 2008. Retrieved December 15, 2005.

- ^ Robert Barnett; Cathy Sears (October 11, 1991). "JAMA gets into an Indian herbal jam". Science. 254 (5029): 188–189. Bibcode:1991Sci...254..188B. doi:10.1126/science.1925571. JSTOR 2885745. PMID 1925571.

- ^ Pettus 1995, p. 31; "Deepak's Days in Court". The New York Times. August 18, 1996.

- ^ Kazak, Don (March 5, 1997). "matDon Kazak, "Book Talk", Time (March 5, 1997)". paloaltoonline.com. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ TNN (April 15, 2001). "The Mind-Body". The Times of India. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ "Deepak Chopra". HarperCollins. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ Presley Noble, Barbara (April 2, 1995). "Spending it: off the Shelf; Habits of Highly Effective Authors". The New York Times. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ^ McGee, Micki (2005). Self-Help, Inc.: Makeover Culture in American Life. Oxford University Press. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-0-19-988368-4. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Butler, J. Thomas. "Ayurveda," in Consumer Health: Making Informed Decisions, Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2011, pp. 117–118.

- Butler, Kurt and Barrett, Stephen (1992). A Consumer's Guide to "Alternative Medicine": A Close Look at Homeopathy, Acupuncture, Faith-healing, and Other Unconventional Treatments. Prometheus Books, pp. 110–116. ISBN 978-0-87975-733-5.

- Kaeser, Eduard [in German] (July 2013). "Science kitsch and pop science: A reconnaissance". Public Understanding of Science. 22 (5): 559–69. doi:10.1177/0963662513489390. PMID 23833170. S2CID 206607585.

- Kafatos, Menas, Nadeau, Robert. The Conscious Universe: Parts and Wholes in Physical Reality, Springer, 2013.

- Nacson, Leon (1998). Deepak Chopra: How to Live in a World of Infinite Possibilities. Random House. ISBN 978-0-09-183673-3.

- Scherer, Jochen. "The 'scientific' presentation and legitimation of the teaching of synchronicity in New Age literature", in James R. Lewis, Olav Hammer (eds.), Handbook of Religion and the Authority of Science, Brill Academic Publishers, 2010.

External links

[edit]- 1946 births

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American non-fiction writers

- 20th-century Indian male writers

- 20th-century Indian medical doctors

- 20th-century Indian non-fiction writers

- 20th-century mystics

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- 21st-century Indian male writers

- 21st-century Indian non-fiction writers

- 21st-century mystics

- All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi alumni

- Alternative medicine activists

- American male non-fiction writers

- American male writers of Indian descent

- American motivational speakers

- American self-help writers

- American spiritual writers

- Ayurvedacharyas

- Celebrity doctors

- HuffPost writers and columnists

- Indian emigrants to the United States

- Indian expatriate academics in the United States

- Indian male non-fiction writers

- Indian motivational speakers

- Indian self-help writers

- Indian spiritual writers

- Living people

- Medical doctors from Delhi

- Nautilus Book Award winners

- New Age spiritual leaders

- New Age writers

- People from New Delhi

- Pseudoscientific diet advocates

- Quantum mysticism advocates

- Recipients of the Medal of the Presidency of the Italian Republic

- St. Columba's School, Delhi alumni

- Transcendental Meditation exponents

- Writers from Delhi

- Ig Nobel laureates

- Anti-fracking movement