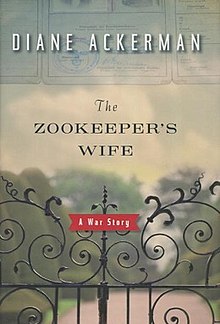

The Zookeeper's Wife

First edition | |

| Author | Diane Ackerman |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | History Biography Non-fiction |

| Publisher | W. W. Norton |

Publication date | September 4, 2007 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Pages | 288 |

| ISBN | 0-393-06172-8 |

| OCLC | 227016807 |

| 940.53/18350943841 22 | |

| LC Class | D804.66.Z33 A25 2007 |

The Zookeeper's Wife is a non-fiction book written by the poet and naturalist Diane Ackerman. Drawing on the diary of Antonina Żabińska, unpublished in English (though published in Polish in 1968[1]), it recounts the true story of how Antonina and her husband, Jan Żabiński, director of the Warsaw Zoo, saved the lives of 300 Jews who had been imprisoned in the Warsaw Ghetto following the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939.[2][3] The book was first published in 2007 by W. W. Norton.

Plot summary

[edit]In the 1930s, Jan Żabiński is the director of a thriving zoo in Warsaw, Poland. His wife, Antonina, has a remarkable empathy with animals, and their villa in the zoo acts as a nursery and residence for numerous animals, as well as for their son. This part of their life abruptly ends with the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, subsequently starting World War II (1939–1945). Most of the zoo's animals and structures are destroyed in the bombings and siege of the city. The zoo is closed under German occupation, but the Żabińskis continue to occupy the villa, and the zoo itself is converted first as a pig farm and subsequently as a fur farm.

Jan and Antonina Żabiński become active with the Polish underground resistance. At the villa and in the zoo's structures, they secretly shelter Jews, most escaping from the doomed Warsaw ghetto. As many as 300 such "guests" pass through the zoo, and many survive the war with the Żabińskis' and the underground's assistance. Although the German occupiers execute those aiding Jews, Antonina Żabińska maintains a semblance of prewar life at the villa, harboring a menagerie of animals – such as otters, a badger, hyena pups, lynxes, and a rabbit – as well as the secret guests.

Jan Żabiński is wounded in the armed August 1944 Warsaw uprising against the German occupiers and, for a time, is interned in a POW camp. The Żabińskis survive the war and the zoo reopens in 1949, with Jan as its new director. On September 21, 1965, Yad Vashem (Israel's official memorial to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust) recognized Jan and Antonina Żabiński as Righteous Among the Nations.[4]

Reception

[edit]Critical reception

[edit]Donna Seaman wrote enthusiastically in her Los Angeles Times review, "It is no stretch to say that this is the book Ackerman was meant to write. Ever since A Natural History of the Senses, she has been building a galaxy of incandescent works that celebrate the unity and wonder of the living world. But every rapturous hour she has spent communing with plants and animals, every insight gleaned into human nature, every moment under the spell of language is a steppingstone that led her to Poland, the home of her maternal grandparents, and to the incomparable heroes Jan and Antonina Zabinski. The result of her tenacious research, keen interpretation and her own "transmigration of sensibility" is a shining book beyond category."[2] D. T. Max wrote in The New York Times, "This is an absorbing book, diminished sometimes by the choppy way Ackerman balances Antonina's account with the larger story of the Warsaw Holocaust. For me, the more interesting story is Antonina's. She was not, as her husband once called her, "a housewife," but the alpha female in a unique menagerie."[5]

For Orion Magazine Susanne Antonetta wrote: "Ackerman, with her profound understanding of nature, tells Antonina's story in a way that makes it clear her roles as the zookeeper's wife and heroine of the Resistance are inextricably connected, both in what the natural world has taught her, and taught her to accept."[6]

Popular reception

[edit]On February 10, 2008, the book was number 13 on The New York Times non-fiction best seller list.[7]

Honors

[edit]In 2008, The Zookeeper's Wife won the annual Orion Book Award from Orion Magazine; the selection committee noted, "The Zookeeper's Wife is a groundbreaking work of nonfiction in which the human relationship to nature is explored in an absolutely original way through looking at the Holocaust."[8]

Adaptations

[edit]In 2013, plans were announced for an eponymous feature film adaptation. The film is based on a screenplay by Angela Workman, directed by Niki Caro, and starring Jessica Chastain,[9][10] Johan Heldenbergh, Michael McElhatton and Daniel Brühl. The film was released on March 31, 2017.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ Żabińska, Antonina, Wydawnictwo Literackie (2017). Ludzie i zwierzęta (in Polish). Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. ISBN 978-83-08-06322-4. OCLC 982629503.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Seaman, Donna (September 2, 2007). "Strange Sanctuary". The Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Foran, Charles (December 15, 2007). "Antonina's Ark". The Globe and Mail. Toronto.

- ^ "Hiding in Zoo Cages: Jan & Antonina Zabinski, Poland". Yad Vashem Remembrance Authority. Retrieved 2013-09-02.

- ^ Max, D. T. (September 9, 2007). "Antonina's List". The New York Times.

- ^ Antonetta, Susanne (November–December 2007). "Reviews – The Zookeeper's Wife: A War Story". Orion Magazine.

- ^ The New York Times Non-Fiction Best Seller List For February 10, 2008

- ^ "2008 Orion Book Award Winner". Orion Magazine. April 1, 2008.

- ^ Kit, Borys (April 30, 2013). "Jessica Chastain Attached to Star in 'The Zookeeper's Wife' (Exclusive)". Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ The Zookeeper's Wife at IMDb

- ^ Elavsky, Cindy (September 21, 2015). "Celebrity Q&A". Celebrity Extra Online. King Features. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Linfield, Susie (September 7, 2007). "A Natural History of Terrible Things". The Washington Post.

At the heart of the Nazis' madness, she implies, lay a paradoxical refusal to control our most amoral impulses on the one hand and to accept the natural world's imperfections on the other.