The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (cartoon)

| The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne | |

|---|---|

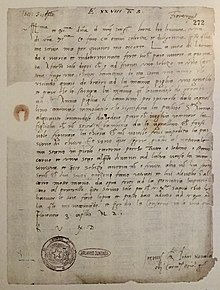

Presumed painting of the cartoon by Andrea del Brescianino (1515–1517) | |

| Artist | Leonardo da Vinci |

| Year | between 1500 and April 1501 |

| Movement | Italian Renaissance |

| Subject | Religious art |

| Condition | Lost |

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne is a cartoon said to have been created by Leonardo da Vinci as part of his "Virgin and Child with Saint Anne" project, and now considered lost. It is known from a letter written on April 3, 1501, by Fra Pietro Novellara, Isabella d'Este's envoy to the painter. For this reason, it is sometimes referred to as "Fra Pietro's cartoon". Although still hypothetical, its existence seems to be confirmed by paintings by Raffaello and Andrea del Brescianino that are said to have been made from it, as well as by various pencil studies.

The drawing, if it ever existed, features some of the most important figures in Christianity. It is a full-length portrait depicting a group formed by Mary seated on the lap of her mother, Saint Anne, and stretching out her arms towards her son Jesus of Nazareth, who is riding a lamb at her feet. The drawing evokes the moment when Jesus challenges his mother to accept his future Passion, aided by his grandmother, who also symbolizes the Church.

Dated between 1500 and April 1501, this is the second of three cartoons the painter needed to create the painting The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne in the Louvre: it follows the abandoned Burlington House cartoon by a few months, and precedes by a year to a year and a half the equally lost cartoon from which the Louvre painting is derived. It marks a significant stage in the painter's thinking: he abandons the figure of St. John the Baptist in favor of that of the lamb; and while it bears great similarities to the painting, the cartoon differs mainly in that its figures adopt a more upright posture and are oriented in an inverted left-to-right image.

The composition, and in particular the motif formed by the Infant Jesus straddling the lamb, met with some success among the painter's followers. This motif can be found in works by Raphael, Bernardino Luini and Giampietrino.

The work

[edit]

Description

[edit]Although the cartoon is lost, researchers have a picture of it, if not a precise one, at least one that contains significant elements. They rely on the description given by the Carmelite monk Fra Pietro da Novellara in a letter to Isabella d'Este dated April 3, 1501:

"[...] Since taking up residence in Florence, [Leonardo da Vinci] has produced only one cartoon project, depicting the Infant Jesus, aged about one year, who has almost escaped from his mother's arms. He turns to a lamb and seems to wrap his arms around it. The mother, almost rising from St. Anne's lap, holds the Child firmly, separating him from the lamb (a sacrificial animal) that signifies the Passion. Saint Anne, who rises a little, seems to want to hold back her daughter, so that she doesn't separate the Child from the lamb [...]. And these figures correspond to their natural sizes, and the reason they fit into this modest-sized cartoon is that they are all seated or leaning, and are placed one behind the other, facing to the left. This project is not yet complete. He hasn't done anything else, except that two of his boys draw copies and he sometimes puts his hand to them."[Note 1]

Fra Pietro da Novellara presents three figures – the Infant Jesus, his mother Mary and Saint Anne – and evokes the presence of a lamb, but not that of John the Baptist.[1] He describes their attitudes: all the figures are seated, one behind the other; however, the two women, bent over, are about to stand up.[2] He also shows Saint Anne preventing the Virgin from separating the baby Jesus from the sacrificial lamb.[3] Finally, he specifies that the drawing is organized "left-handed" ("la man sinistra"), which corresponds to the opposite direction of the painting in the Louvre.[4][Note 2]

Subject

[edit]The cartoon of Saint Anne, the Virgin and the Child Jesus is part of the Christian iconographic theme of the "Trinitarian Saint Anne", in which the Child Jesus, his mother Mary and his grandmother Anne are depicted together.[5] The painting of The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne was Leonardo da Vinci's first work to depict the subject.[6]

This theme enters into the context of the Marian cult,[7] in particular to justify the dogma of the Immaculate Conception,[7][8] according to which Mary, receiving in anticipation the fruits of the resurrection of her son Jesus Christ, was conceived free from original sin.[Note 3] This miracle meant that her own mother, Anne, gained in theological importance.[7] From then on, the cult of Saint Anne grew, so that the "Trinitarian Saint Anne" became an earthly trinity in reference to the heavenly Trinity.[8] Shortly before Leonardo da Vinci's period of activity, Pope Sixtus IV encouraged this cult by introducing an indulgence that promised remission of sins to anyone who prayed before the image of Anna metterza (Saint Anne, the Virgin and Child).[9] A few examples of the triad of Saint Anne, the Virgin and the Child can be seen in the 13th and 14th centuries, before this iconographic theme gained in importance at the end of the 15th century, mainly in the form of sculptures and paintings.[5]

History of the piece

[edit]A presumption of existence sometimes controversial

[edit]- Two paintings almost identical to Novellara's description

-

Andrea del Brescianino, Sainte Anne after the cartoon by Leonardo da Vinci, 1515–1517, lost, Berlin, Kaiser-Friedrich Museum.

-

Raffaello del Brescianino (?), Saint Anne, copy of the Kaiser-Friedrich Museum painting, 1515–1517, Madrid, Prado Museum, inv. no. P000505.

As evidence of the research that led to the creation of the Louvre's Sainte Anne, we have the Burlington House cartoon, three composition drawings and thirteen detail studies preserved around the world.[10]

In 1887, a letter dated April 3, 1501, addressed to Isabella d'Este by her envoy to the painter in Florence, the Carmelite monk Fra Pietro Novellara, was discovered in the Mantua archives: in which he describes in great detail a cartoon by Leonardo da Vinci that he has just seen.[11] Researchers at the end of the 19th century considered this to be a description of the cartoon used by the painter to begin the painting of Saint Anne, since the general outline (characters and composition) was very similar.[2] This confusion is exacerbated by the fact that Giorgio Vasari's Vite refers to the exhibition of a cartoon in Florence's Santissima Annunziata at the beginning of the 16th century, which would have included Saint Anne, the Virgin Mary, the Child Jesus, the Lamb and Saint John:[12][Note 4] this testimony then creates a vagueness between Fra Pietro's cartoon, the one in Burlington House, which slightly precedes it, and the one for the painting of Saint Anne, which is one or two years older.[13][14]

Yet Novellara's testimony contains significant elements that dissociate them: on the one hand, the presence of a lamb completely rules out the Burlington House Cartoon composition; on the other hand, the figures are described as facing to the left, whereas the figures in the Saint Anne painting face to the right.[8] It wasn't until 1929 that Austrian art historian Wilhelm Suida identified these inconsistencies.[15] He made a comparison with two paintings by the brothers Raffaello (?) and Andrea del Brescianino, guided by the similarities of the text with the composition, the attitude of the figures and their "left-hand" orientation.[2][16]

For some, however, this theory is still stumped by the orientation described by Novellara: perhaps he was looking from the point of view of the figure (which would correspond to the orientation of the painting in the Louvre) and not from that of the viewer (corresponding to an opposite orientation). In 1979, Carlo Pedretti confirmed the hypothesis of the viewer's orientation to the left with the discovery of a study he believed might be by the master's hand,[Note 5] and in any case contemporary with it.[2] Since then, a number of researchers have rallied around the idea of a second cartoon: in addition to Carlo Pedretti, they include Daniel Arasse,[17] Carmen C. Bambach,[18] Vincent Delieuvin[19] and Frank Zöllner.[11]

Dating

[edit]The dating of this cartoon, produced as part of a project to compose a "Trinitarian Saint Anne", which led to the painting The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne in the Louvre, is fairly well circumscribed: it is dated after the creation of the Burlington House Cartoon,[Note 6] i.e. after 1500,[20] and cannot be later than its public exhibition in April 1501.[11]

The fate of the cartoon is totally unknown after its exhibition in Florence and the painter's departure from the city.[21]

A creation within the framework of the creation of a Saint Anne

[edit]By 1501, Leonardo da Vinci, who was approaching fifty,[22] was a recognized painter, and his fame extended beyond the Italian peninsula.[23] Nevertheless, his life was in an important phase of transition: in September 1499, Louis XII's French invaded Milan, and the painter lost his powerful patron Ludovico il Moro.[24] He then hesitated about his allegiances: should he follow his former protector or turn to Louis XII, who quickly made contact with him?[25] Nevertheless, the French quickly became hated by the population, and Leonardo decided to leave. This exile, described by his contemporaries as erratic,[Note 7] took him first to Mantua – to the Marchioness Isabella d'Este, for whom he created a cartoon for his portrait – then to Venice, and finally to his native Florence.[22]

According to a chronology widely spread within the scientific community, Leonardo da Vinci was commissioned to paint a Saint Anne around 1499–1500, by an unspecified patron.[26] In the early 1500s, he drew up a first cartoon – the Burlington House Cartoon – as an initial idea for the composition.[6] Abandoning this proposal, he quickly created a second one, in which he discarded the infant John the Baptist in favor of a lamb: this would thus be the cartoon The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, known as "of Fra Pietro", exhibited in Florence in April 1501, taken over by Raphael and now lost.[8][27] Setting aside his composition once again, the painter finally created a final cartoon from which the painting The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, now in the Louvre, would emerge.[28]

In the end, although this project for a "Trinitarian Saint Anne" seems to have taken shape around 1499–1500, with the painting of the Louvre picture beginning around 1503, the process took much longer, since it covered the last twenty years of the painter's life, and the picture was still unfinished when he died in 1519.[29]

Title

[edit]As the reality of this cartoon is still hypothetical despite its very high probability, there is no established title truly attributed to it: authors refer to it as "first"[30] or "second cartoon"[2] depending on the theory retained by each researcher as to the dating of the projects leading to the Saint Anne painting. In the same way that the first of the three cartons has been named by the scientific community as the Burlington House Carton,[21][31] Vincent Delieuvin calls it the "Fra Pietro cartoon" to differentiate it from the other two.[2]

Finally, it would be possible to take into account the titles given to the works that resulted from them (in greater or lesser proportion): The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne or directly Sainte Anne for the one created by Andrea del Brescianino; The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne for the painting by Leonardo da Vinci of which it is a preparatory stage.[16][21][32] In fact, only Daniel Arasse seems to name it directly: "Leonardo was working in Florence in 1501 [...] on the second cartoon (no longer existing) of "The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne", a title which, under his pen, constitutes the generic title of any work leading to the painting in the Louvre.[17]

Creation

[edit]Inspiration sources

[edit]-

Benozzo Gozzoli, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Donors, c. 1470, Pisa, National Museum of San Matteo.

Leonardo designed his carton as part of a large-scale production linked to the theme of the "Trinitarian Saint Anne". He drew his inspiration from the composition of The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Donors by Benozzo Gozzoli (circa 1470), in which the figures are placed one above the other diagonally.[33] He also drew on the Adoration of the Magi by Filippino Lippi (1496), notably by reorienting the figures to the left[34] and replacing the figure of Joseph with Saint Anne. Finally, the master combines the two compositions to create his own proposal: he enlivens Gozzoli's composition with the dynamism of the Joseph-Marie-Jesus group in Filippino Lippi's painting.[33]

Studies

[edit]-

Leonardo da Vinci, verso of Composition Study for Saint Anne, c. 1500 or c. 1505–1508, London, British Museum, no. inv. 1875,0612.17v.

-

Leonardo da Vinci, Study for Saint Anne, the Virgin and Child Jesus, 1501, Paris, Louvre, graphic arts department, inv. no. RF 460.

-

Leonardo da Vinci, Studies for the Christ Child with a Lamb, c. 1500-1501 (?), Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, ref. no. 86.GG.725.

-

Leonardo da Vinci, Study for the head of Saint Anne, circa 1501, Windsor Castle, The Royal Collection, Royal Library, RL 12534.

Researchers have identified several drawings by Leonardo da Vinci as studies for the cartoon. The first, whose autograph nature is sometimes debated, is in the British Museum collections under inventory number 1875,0612.17v:[34][35] it is a drawing on the verso of a study for the Burlington House Cartoon, obtained by transferring certain strokes of the composition from the recto to the verso with a drypoint, the latter being placed on a support rubbed with charcoal.[36] Although the drawing still shows John the Baptist as a child and not a lamb, it is the first indication that the composition could be constructed and read in the opposite direction to that of the Burlington House cartoon.[34][37]

The second drawing is in the collections of the Graphic Arts Department of the Louvre under inventory number RF 460.[34] The orientation of the figures is the opposite of the Burlington House Cartoon and the painting in the Louvre: Leonardo confirms that he "envisaged both directions of reading."[38] Clearly satisfied with the postures of Mary and her mother – whose lines are quite clear – the painter is apparently still looking for those of baby Jesus and his companion above and to the left of Mary's legs – whose lines have been heavily retouched during the creation of the drawing, producing almost indistinct shapes.[Note 8] In any case, the Child remains on his mother's lap, as in the Burlington House Cartoon.[39] Likewise, the painter still seems unsure of the identity of the scene's fourth protagonist, hidden in the mass on the left: it appears to be a lamb – as in the Louvre painting – whose snout can be guessed to the left of Jesus' head, and the rest of his body stretched out on the bench occupied by Saint Anne.[38][40] A final lesson from the drawing is that the Child Jesus seems to be turning his face towards the two women: ready for his own sacrifice, he would like to reassure his mother; her smile marks the beginning of her acceptance. Such an accumulation of clues would confirm that Fra Pietro's cartoon is indeed a transition between the Burlington House Cartoon and the painting in the Louvre.[40]

Following on from the Louvre drawing, a sketch sheet kept at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles under inventory number 86.GG.725 contains a series of studies that focus exclusively on the group of Jesus and the lamb,[41] independently of the rest of the composition.[Note 9][42] The interest of this document is twofold. Firstly, it reflects the evolution of the painter's thoughts on his composition: he keeps Jesus at the same level as the lamb, but now seems to be placing them on the ground. In addition, a very direct link can be made between this composition and the drawing preserved at the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice under inventory number 230: among other arguments, this allows us to consider the latter as a study of Fra Pietro's cartoon, despite its opposite orientation.[43] Also of interest to researchers, the drawing contains a few notes, at the top of the sheet in its mirrored script, relating to a geometric treatise written in the 11th century by the Spanish-Jewish mathematician Abraham bar Hiyya Hanassi (c. 1070 – c. 1136 or c. 1145):[Note 10] art historian Carmen C. Bambach links this note with Fra Pietro Novellara's assertion that Leonardo da Vinci was simultaneously absorbed in mathematical studies and the design of a Saint Anne,[Note 11] making the cleric's testimony even more credible.[44]

Preserved at the Royal Library under inventory number RL 12534, a fourth drawing is the last known study for Fra Pietro's Cartoon, but its autograph character is also debated,[45] as are the figure it depicts[46] and its dating.[47] It shows a woman's face whose pose, hairstyle and smile are reminiscent of Saint Anne in the Louvre painting. Only its orientation to the left dissociates it from this, and links it resolutely to the second cartoon. The drawing bears witness to the painter's search for an ideal head for Saint Anne, as it would have appeared on the cartoon and which he kept for the work in the Louvre.[45]

Analysis

[edit]

Composition

[edit]The composition of Fra Pietro's cartoon is deduced from the indications given by Pietro Novellara. But it is also deduced from the two paintings by the Brescianino brothers: it should be borne in mind that the idea that these works perfectly reflect Leonardo da Vinci's original composition remains a hypothesis.[16]

With the exception of the arrangement of the figures to the left, the composition is very similar to that of the painting in the Louvre – which may have led to the two works being confused in the past: Mary is seated on St. Anne's lap and, in line with their gaze, the Child Jesus stands at their feet. Together, they form a diagonal construction descending to the left in a right-angled triangle, the hypotenuse of which passes through the heads of the four protagonists (including the lamb).[2] The composition of Fra Pietro's cartoon thus differs from the previous proposal – the Burlington House Cartoon – by abandoning the horizontal construction: it thus constitutes a return to a hierarchical vision of the theme, with Saint Anne overlooking her daughter, herself situated above Jesus.[48] Moreover, Daniel Arasse considers that the painter is correcting the "unfinished" composition of the previous cartoon, where "the two female figures [were] not clearly articulated" and where "Saint Anne [only] occupied a very secondary place plastically": the new cartoon would thus allow the figure of Saint Anne to be emphasized thanks to the vertical scheme.[49]

Finally, the arrangement of the figures is such that the posture and gestures of each one seem to continue those of the previous one, as when a movement is decomposed: "Saint Anne's left shoulder continues into the Virgin's left arm, which itself finds continuity in Christ's forearm."[48] This dynamic arrangement is not new, since Leonardo da Vinci found it in Filippino Lippi's Adoration of the Magi;[33] but the scene thus acquires its own kinematics, induced by the movement created, and sustained by the slight rotational effect of the whole "initiated by the position of the bodies, slightly out of alignment with each other."[50]

From Saint John the Baptist to the Lamb

[edit]-

Leonardo da Vinci, Study for the Madonna of the Cat, c. 1480, British Museum, inv. no. 1856,0621.1v.

-

Leonardo da Vinci, Composition study for a Trinitarian Saint Anne with a lamb, c. 1500–1501, Venice, Gallerie dell'Accademia, no. inv. 230.

When it came to composing his new cartoon, Leonardo da Vinci decided to change a number of elements, and in particular to abandon the figure of Saint John the Baptist as a child for a lamb. Researchers don't know the reasons for such a change: was it the commissioner's wish, or did he seek a better composition?[51]

Here, Leonardo da Vinci is proposing a realistic representation of the animal[51] rather than the heraldic representation often used in Italian Renaissance art, where it appears within a disc or resting on a book.[52] The lamb is one of the attributes of Saint John the Baptist in Western art,[Note 12] in reference to his welcoming of Jesus with the words: "Behold the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world",[53][54] making the lamb "the double of Jesus himself."[55] This is why Saint John the Baptist is associated with the lamb, as one respectively announces and the other symbolizes the Passion of Christ:[8] in fact, in a more direct and coherent scheme, the painter substitutes the bearer of the announcement of the Passion present in the first cartoon with the symbol of the event.[56][57]

Such a proposal is in line with the painter's research, carried out in the 1480s,[58] depicting Jesus with a cat. Indeed, the association or interchangeability of the two animals is present in the research of the painter and his entourage: for example, in a painting by the Spanish Leonardeschi painter Hernando de los Llanos (or Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina)[Note 13] inspired by several of the master's drawings on the theme of the Madonna with cat, scientific imagery shows that the lamb held by the Child was originally a cat.[59][60] This filiation enabled the painter to answer the following questions: where should the lamb and the Child be placed? What interactions should be established between these two figures? The first instance of the lamb figure is the drawing in the Louvre (inv. no. RF 460), which shares many similarities with his Study for the Madonna of the Cat (1479–1480): in both cases, the animal is placed in the arms of Christ, who is himself on his mother's lap.[61][Note 14] After the Louvre drawing, the lamb also appears in the Venice drawing (inv. no. 230), which is slightly later: this time, Leonardo da Vinci places it on the ground, but the Child remains on his mother's lap.[58] These moves are completed in Fra Pietro's Cartoon, where the two figures are placed at the Virgin's feet, with the Child straddling the animal.[62]

The benefit to the painter of eliminating John the Baptist is threefold. Firstly, it makes the composition more compact: the construction can focus on the three figures of the family and thus become vertical again – in the iconographic tradition of the theme – to emphasize the succession of generations.[61] What's more, the refocused narration removes the double visual dialogue between Mary/Anne and Jesus/Saint John the Baptist and becomes a three-way dialogue, as confirmed by the rotation of baby Jesus towards his mother. Finally, this choice introduces another element of dynamism – that of the little animal, along with that of the Child – which the calm of the Baptist figure did not allow in the Burlington House Cartoon.[51]

Interpretation

[edit]

Leonardo da Vinci captures the moment when Mary is challenged by her mother and son to accept the latter's sacrifice. Unlike traditional representations of the "Trinitarian Saint Anne", which are generally mere symbolic images, the painter offers a true narrative, depicted "like a family genre scene in which a grandmother and her daughter observe the seemingly innocent play of the Child", whose purpose is to reveal God's goal: the sacrifice of his son for the salvation of humanity.[50]

This interpretation is summed up by Fra Pietro Novellara in his letter to Isabella d'Este, contemporaneous with the work's creation. First, he describes how "the Child Jesus, about a year old, has almost escaped from his mother's arms. He turns to a lamb and seems to wrap his arms around it."[62] Jesus' gesture of "embracing" the animal is understood as an acceptance of his destiny – an acceptance accentuated by the fact that the Child has joined him on the ground.[63] But Andrea del Brescianino's painting also shows him turning towards his mother, as a sign of comfort and an invitation to accept his fate.[8]

However, the Virgin Mary reacts protectively towards her son: "The mother, who almost rises from Saint Anne's lap, holds the Child firmly to separate him from the lamb – a sacrificial animal that signifies the Passion."[62] At the same time, says Pietro Novellara, "Saint Anne, who rises a little, seems to want to hold back her daughter, so that she does not separate the Child from the lamb."[64] However, this gesture is discreet: she only holds her daughter back with her fingertips, as she seems to accept her son's future death,[65] and is no longer obliged to invoke Heaven by pointing her index finger at it, as was the case in the Burlington House Cartoon.[66]

Lastly, Novellara's testimony suggests a double reading: Anne, who prevents her daughter from holding back Jesus, is not simply Mary's mother, but also represents the Church ("Saint Anne, who stands up a little, seems to want to hold back her daughter, so that she does not separate the child from the lamb. This perhaps represents the Church, which does not wish to prevent the Passion of Christ").[64] The man was in fact an eminent member of the clergy: a renowned preacher, he had been vicar-general of the Bologna chapter since May 3, 1499, and remained so until May 3, 1501, after which he became prior of the Mantua convent.[4] As a simple believer, he believed that Christ's destiny was the Passion, and as a member of the clergy, he necessarily considered that the Church must prevent Mary from diverting Christ from this destiny.[67]

Posterity

[edit]

Fra Pietro's cartoon is not the subject of any autograph painting. Nevertheless, scholars – led by Austrian art historian Wilhelm Suida – consider that its composition was soon faithfully reproduced in two paintings. The earliest was painted between 1515 and 1517 by Andrea Piccinelli, known as "Il Brescianino", and was kept in Berlin's Kaiser-Friedrich Museum from 1829 until its destruction in 1945. Another artist – perhaps his brother Raffaello[68] – produced a copy around the same period, now in the Museo del Prado in Madrid.[69] Art historians consider that Andrea del Brescianino created his painting from an unfinished cartoon – which corresponds to the state in which Fra Novellara could observe it in April 1501 – because a description of the lost painting describes a color palette and treatment of faces quite unusual for Leonardo da Vinci.[16]

- The success of the Child Riding the Lamb motif on Fra Pietro's Cartoon

-

Giampietrino, Madonna and Child with Saints Jerome and John the Baptist, circa 1515, Ospedaletto Lodigiano, parish church.

-

Bernardino Luini, The Virgin with Jesus and John the Baptist as Children, c. 1529–1532, Switzerland, Lugano, Church of St Mary of the Angels.

-

Anonymous after Bernardino Luini, Holy Family with St. John the Baptist and St. Elizabeth, first half of the 16th century, Copenhagen, Bruun Rasmusen Bredgade.

-

Anonymous Florentine, Madonna and Child, early 16th century, private collection.

-

Anonymous Lombard, Madonna and Child, 16th century, Milan, Archinto collection.

Although the cartoon was eventually abandoned by the master, it was still an extremely useful project for the Saint Anne in the Louvre: Leonardo definitively abandoned the figure of St. John the Baptist in favor of the lamb, and solved the problem of positioning baby Jesus and the lamb at Mary's feet.[63] As for the positions and poses of the two women, they are merely a variation on what could be seen on the cartoon. Finally, the importance of the latter for the painting is such that it can be considered to "unquestionably provide the iconological and formal matrix for the Sainte Anne in the Louvre."[4]

According to Sarah Taglialagamba, the cartoon's impact was "considerable" and therefore "quickly reused by Leonardo's followers."[30] They readily imitated the motif of the Child straddling a lamb, usually under the gaze of his mother.[70] One of its earliest occurrences dates back to 1507, with Raphael's Holy Family with a Lamb: the painter uses the Virgin, Child and Lamb, but St. Anne is replaced by St. Joseph.[71] Although he reused the three main figures from the cartoon, it was above all this motif that Bernardino Luini also repeated in several paintings: The Virgin with Jesus and John the Baptist as Children, a fresco in the Church of St Mary of the Angels in Lugano dating from the first quarter of the 16th century; and another from which a follower drew the Holy Family with St. John the Baptist and St. Elizabeth. Giampietrino also uses it at least twice, each time showing Jesus in the company of Saint John the Baptist.[70]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ « Illustrissima et exellentissima Domina, Domina nostra singularissima. Hora ho havuta una di Vostra excellencia et farò cum omni celerità et diligencia quanto quella me scrive. Ma per quanto me occorre, la vita di Leonardo è varia et indeterminata forte siché pare vivere a gornata. A facto solo dopoi che è ad Firenci uno schizo in uno cartone; finge uno Christo bambino de età cerca uno anno che uscindo quasi de bracci ad la mamma piglia uno agnello et pare che lo stringa. La mamma quasi levandose de grembo ad Sta Anna piglia el bambino per spicarlo dalo agnellino (animale immolatile) che significa la Passione. Sta Anna alquanto levandose da sedere pare che voglia retenere la figliola che non spica el bambino da lo agnellino. Che forsi vole figurare la Chiesas che non vorebbe fussi impeditala Passione di Christo. Et sono queste figure grande al naturale ma stano in picolo cartone perché tutte o sedino e stano curve et una stae alquanto dinanci ad l'altra verso la man sinistra. Et questo schzo ancora non e finito. Altro non ha facto senon che dui suoi garzoni fano retrati et lui ale volte in alcuno mette mano. Da opra forte a la geometria impacientissimo al pennello. Questo scrivo solo perché Vostra Excellencia sapia ch'io ho havute le sue. Farò l'opra et preso darò adviso ad Vostra Excellencia ad laquale mi racomoando. Et prego Dio la conservi in la sua gracia. Florencie 3 aprillis M.D.I. » The original quotation and translation to French are from Zöllner (2017, Chap. VII) Return to Florence via Mantua and Venice – 1500–1503, p. 221-222.

- ^ The various French translations of the phrase "ad l'altra verso la man sinistra" are as follows: Zöllner (2017, Chap. VII) suggests "turned to the left", Hohenstatt (2007, p. 83), "in a movement directed to the left" and Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 77), "one stands somewhat in front of the other on the left hand".

- ^ She was therefore not corrupted by the initial fault that has since given every human being a tendency to commit evil. According to the Catholic Church's definition, this is "the privilege whereby, by virtue of an exceptional grace, the Virgin Mary was born preserved from original sin. The dogma of the Immaculate Conception was proclaimed by Pius IX in 1854. Not to be confused with the virginal conception of Jesus by Mary", as defined by the Conférence des évêques de France (French Bishops' Conference), "Immaculée Conception". eglise.catholique.fr. 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ Vasari speaks of a "little Saint John having fun with a lamb". Quoted in Pedretti & Taglialagamba (2017, p. 126)

- ^ However, this attribution is still disputed by a number of the researcher's colleagues. Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 74)

- ^ Nevertheless, the dating of the Burlington House Cartoon is the subject of wide disagreement among researchers, some of whom estimate that it was created after 1506. Temperini (2003, p. 42)

- ^ Fra Pietro Novellara, Isabella d'Este's envoy to the painter, testified: "his existence is so unstable and uncertain that he seems to be living from day to day". Vezzosi (2010, p. 83)

- ^ Art historians refer to this creation as "componimento inculto", the process of repeatedly ironing over strokes to create a drawing with indistinct lines. Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 64)

- ^ Two other documents bear identical studies, including one preserved at Windsor Castle under reference number RL 12540. "A seated youth, and a child with a lamb c. 1503-6". rct.uk. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ "jicipit liber.endaborum.assauasorda.judeo inebraicho coposit[us] et a platone/tiburtinj inlatin sermone translat[us] anno. arabu.dx. mse sap h ar/capi tulu pimu ingeometrice arihmetrice (p) vnyversalia proposita:" and "franco.o dif." quoted in Getty."Studies for the Christ Child with a Lamb (recto); Head of an Old Man, and Studies of Machinery (verso)". getty.edu. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ "And this sketch isn't finished yet. He has done nothing else, except that two of his boys draw copies and he sometimes puts his hand to it. He's very fond of geometry, suffers very badly with the brush." Zöllner (2017, pp. 221–222, Chap. VII. Retour à Florence par Mantoue et Venise – 1500–1503)

- ^ Other attributes include the long, thin metal cross of Eastern origin: following the Quinisext Council of 692, the representation of the lamb was banned in the Eastern Church and replaced by that of the cross. Mâle (1951, p. 56) The attribute then migrated to the West, after which it is found in other works by the painter, such as the London version of Virgin of the Rocks – though certainly by another hand.Marani & Villata (1999, p. 139)

- ^

Hernando de los Llanos (?), Virgin and Child with Lamb, c. 1502–1505, Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera, no. inv. 1168.

- ^ Nevertheless, the presence of a lamb has not been clearly established, although a recent scientific imaging analysis would point to this. Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 64)

References

[edit]- ^ Zöllner (2017, Chap. VII)

- ^ a b c d e f g Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 74)

- ^ Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 4, Press dossier)

- ^ a b c Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 78)

- ^ a b Le Tourneau, Dominique (2005). Les mots du Christianisme: Catholicisme, orthodoxie, protestantisme. Fayard. p. 21. ISBN 978-2-213-62195-1. OCLC 912397060.

- ^ a b Delieuvin et al. (2019, booklet)

- ^ a b c Hohenstatt (2007, p. 80)

- ^ a b c d e f Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 11, Press dossier)

- ^ Hohenstatt (2007, pp. 80–83)

- ^ Delieuvin (2019, p. 274, catalogue)

- ^ a b c Zöllner (2017, p. 400, Catalogue critique des peintures, XXII)

- ^ Vasari, Giorgio (1839). "Léonard de Vinci, Peintre florentin". Le Vite de' più exxellenti architetti, pittori et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri [Vies des peintres sculpteurs et architectes] (in French). Vol. 4. Translated by Leclanché, Léopold. Paris: Just Tessier. pp. 15–16. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 8, Press dossier)

- ^ Zöllner (2017, pp. 401–402, Catalogue critique des peintures, XXII)

- ^ Suida, Wilhelm (1929). Leonardo und sein Kreis [Leonardo and his circle] (in German). Munich: Bruckmann. p. 327. OCLC 185401310.

- ^ a b c d Zöllner (2017, pp. 400–401, Catalogue critique des peintures, XXII)

- ^ a b Arasse (2019, p. 255)

- ^ Leonardo; Bambach, Carmen; Stern, Rachel; Metropolitan Museum of Art, eds. (2003). "Drawing the boundaries". Leonardo da Vinci, master draftsman: Exhibition "Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman" organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and held there from January 22 to March 30, 2003. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art [u.a.] ISBN 978-1-58839-034-9.

- ^ Delieuvin et al. (2012, pp. 74–76)

- ^ The National Gallery. "The Burlington House Cartoon". nationalgallery.org.uk. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c Pedretti & Taglialagamba (2017, p. 126)

- ^ a b Bramly (2019, p. 448)

- ^ Bramly (2019, p. 443)

- ^ Bramly (2019, p. 438)

- ^ Bramly (2019, p. 439)

- ^ Zöllner (2017, p. 393, Catalogue critique des peintures, XX)

- ^ Harding et al. (1989, p. 5)

- ^ Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 10, Press dossier)

- ^ Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 20, Press dossier)

- ^ a b Pedretti & Taglialagamba (2017, pp. 126, 128)

- ^ Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 45, Press dossier)

- ^ Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 38, Press dossier)

- ^ a b c Zöllner (2017, pp. 222–223, Chap. VII)

- ^ a b c d Zöllner (2017, p. 401, Catalogue critique des peintures, XXII)

- ^ The Trustees of the British Museum (2019). "Asset number 218863001 – Description – Verso". britishmuseum.org. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Kemp, Martin (2003). "Drawing the boundaries". In Leonardo; Bambach, Carmen; Stern, Rachel; Metropolitan Museum of Art (eds.). Leonardo da Vinci, master draftsman: Exhibition "Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman" organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and held there from January 22 to March 30, 2003. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art [u.a.] pp. 141–154. ISBN 978-1-58839-034-9.

- ^ Leonardo; Bambach, Carmen; Stern, Rachel; Metropolitan Museum of Art, eds. (2003). Leonardo da Vinci, master draftsman: Exhibition "Leonardo da Vinci, Master Draftsman" organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and held there from January 22 to March 30, 2003. New York, NY: Metropolitan Museum of Art [u.a.] pp. 242, 722, 528. ISBN 978-1-58839-034-9.

- ^ a b "VINCI Leonardo da – Ecole florentine – Sainte Anne, la Vierge et l'Enfant". arts-graphiques.louvre.fr (in French). Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Delieuvin et al. (2012, pp. 66–67)

- ^ a b Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 67)

- ^ "Studies for the Christ Child with a Lamb (recto); Head of an Old Man, and Studies of Machinery (verso)". getty.edu. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ Bambach (2003, pp. 516–519)

- ^ Bambach (2003, p. 516)

- ^ Bambach (2003, pp. 519–520)

- ^ a b Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 80)

- ^ Ewart Popham, Arthur (1945). The drawings of Leonardo da Vinci. Reynal & Hitchcock. p. 51.

- ^ Clayton, Martin. "The head of the Madonna(?)". rct.uk. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ a b Delieuvin (2019, pp. 280–281, catalogue)

- ^ Arasse (2019, p. 351)

- ^ a b Delieuvin (2019, p. 281, catalogue)

- ^ a b c Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 64)

- ^ Mâle (1951, pp. 55–56)

- ^ Gospel of John 1:29

- ^ Mâle (1951, p. 55)

- ^ Arasse (2019, p. 354)

- ^ Delieuvin et al. (2012, pp. 47, 75)

- ^ Arasse (2019, p. 355)

- ^ a b Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 65)

- ^ Popham, Arthur E.; Pouncey, Philip. "Drawing – Museum number 1856,0621.1". britishmuseum.org. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 258)

- ^ a b Delieuvin et al. (2012, pp. 64–65)

- ^ a b c Zöllner (2017, p. 221, Chap. VII. Retour à Florence par Mantoue et Venise – 1500–1503)

- ^ a b Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 75)

- ^ a b Zöllner (2017, pp. 221–222, Chap. VII. Retour à Florence par Mantoue et Venise – 1500–1503)

- ^ Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 12, Press dossier)

- ^ Delieuvin (2019, p. 279, catalogue)

- ^ Zöllner (2017, pp. 223–230, Chap. VII. Retour à Florence par Mantoue et Venise – 1500–1503)

- ^ Delieuvin et al. (2012, p. 82)

- ^ "La Virgen con el Niño y Santa Ana". Museo del Prado (in Spanish). 2019. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Delieuvin et al. (2012, pp. 86–87)

- ^ "Sagrada Familia del Cordero". Museo del Prado (in Spanish). 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]- Arasse, Daniel; et al. (Les incontournables) (2019). "Les desseins du peintre". Léonard de Vinci (in French). Vanves: Hazan. pp. 204–261. ISBN 978-2-7541-1071-6. OCLC 1101111319.

- Bambach, Carmen C; Vecce, Carlo; Viatte, Françoise; Cecchi, Alessandro; Marani, Pietro C.; Farago, Claire; Forcione, Varena; Logan, Anne-Marie; Wolk-Simon, Linda (2003). Leonardo da Vinci, master draftsman. New York, New Haven: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Yale University Press. ISBN 978-1-5883-9034-9.

- Bramly, Serge; et al. (Essais et documents) (April 24, 2019). "9. Lauriers et orages". Léonard de Vinci: Une biographie (in French). Paris: Jean-Claude Lattès. ISBN 978-2-7096-6323-6.

- Delieuvin, Vincent; Barbe, Françoise; Beuzelin, Cécile; Chui, Sue Ann; Curie, Pierre; Eveno, Myriam; Foucart-Walter, Élisabeth; Frank, Louis; Frozinini, Cecilia; et al. (Ana Gonzalez Mozo, Sophie Guillot de Suduiraut, Claurio Gulli, Bruno Mottin, Cinzia Pasquali, Alan Phenix, Cristina Quattrini, Élisabeth Ravaud, Cécile Scailliérez, Naoko Takahatake) (March 29 – June 25, 2012). "L'exploration du sujet, du carton de Londres au tableau du Louvre". La Sainte Anne: l'ultime chef-d'œuvre de léonard de Vinci (Exhibition catalogue) (in French). Paris: Louvre éditions. ISBN 978-2-35031-370-2. OCLC 796188596.

- Delieuvin, Vincent; Curie, Pierre; Pasquali, Cinzia; Beuzelin, Cécile; Scailliérez, Cécile; Chui, Sue Ann; Gulli, Claudio; et al. (Louvre) (2012). La Sainte Anne, l'ultime chef-d'œuvre de Léonard de Vinci (PDF) (Press dossier). Louvre éditions.

- Delieuvin, Vincent (2019). "162. Sainte Anne, la Vierge, l'Enfant Jésus et saint Jean-Baptiste". Léonard de Vinci: 1452–1519 (blooket distributed to visitors of the exposition at Louvre, from 24 octobre 2019 to 24 février 2020) (in French). Paris: Louvre. ISBN 978-2-85088-725-3.

- Delieuvin, Vincent; Frank, Louis; Bastian, Gilles; Bellec, Jean-Louis; Bellucci, Roberto; Calligaro, Thomas; Eveno, Myriam; Frosinini, Cecilia; Laval, Éric; et al. (Bruno Mottin, Laurent Pichon, Élisabeth Ravaud, Thomas Bohl, Benjamin Couilleaux, Barbara Jatta, Ludovic Laugier, Pietro C. Marani, Dominique Thiébaut, Stegania Tullio Cataldo, Inès Villela-Petit) (2019). Léonard de Vinci (catalogue de l'exposition au musée du Louvre, du 24 octobre 2019 au 24 février 2020) (in French). Louvre éditions, Hazan. pp. 258–289. ISBN 978-2-7541-1123-2. OCLC 1129815512.

- Hohenstatt, Peter; et al. (Maîtres de l'Art italien) (2007). "La percée dans le Milan des Sforza 1482-1499". Meister der italienischen Kunst - Leonardo da Vinci [Léonard de Vinci: 1452-1519] (in French). Translated by Métais-Bührendt, Catherine. Paris: h.f.ullmann - Tandem Verlag. pp. 50–79. ISBN 978-3-8331-3766-2.

- Marani, Pietro; Villata, Edoardo (1999). Léonard de Vinci : Une carrière de peintre. Translated by Anne Guglielmetti. Arles, Milan: Actes Sud, Motta. ISBN 2-7427-2409-5.

- Pedretti, Carlo; Taglialagamba, Sara (October 11, 2017). "II. Du dessin au tableau, Les deux vierges". Leonardo, l'arte del disegno [Léonard de Vinci: L'art du dessin] (in French). Translated by Temperini, Renaud. Paris: Citadelles et Mazenod. pp. 204–211. ISBN 978-2-8508-8725-3.

- Temperini, Ranaud; et al. (ABCdaire série art) (2003). L'ABCdaire de Léonard de Vinci (in French). Arles: Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-010680-3.

- Vezzosi, Alessandro (April 16, 2010). "À Milan au temps des Sforza". Léonard de Vinci: Art et science de l'univers. Découvertes Gallimard / peinture (293) (in French). Translated by Françoise Liffran. Paris: Gallimard. pp. 51–81. ISBN 978-2-0703-4880-0.

- Zöllner, Frank; et al. (Bibliotheca universalis) (2017). Léonard de Vinci, 1452-1519: Tout l'œuvre peint (in French). Cologne: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-6296-6.

Articles

[edit]- Harding, Eric; Braham, Allan; Wyld, Martin; Burnstock, Aviva (1989). "The Restoration of the Leonardo Cartoon". National Gallery Technical Bulletin. 13: 5–27.

- Mâle, Émile (March 1, 1951). "Le type de Saint Jean-Baptiste dans l'art: et ses divers aspects". Revue des deux Mondes. 1–2: 53–62. JSTOR 44590041.