The Song of Los

The Song of Los (written 1795) is one of William Blake's epic poems, known as prophetic books. The poem consists of two sections, "Africa" and "Asia". In the first section Blake catalogues the decline of morality in Europe, which he blames on both the African slave trade and enlightenment philosophers. The book provides a historical context for The Book of Urizen, The Book of Ahania, and The Book of Los, and also ties those more obscure works to The Continental Prophecies, "Europe" and "America".[1] The second section consists of Los urging revolution.

Background

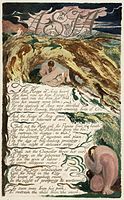

[edit]During autumn 1790, Blake moved to Lambeth, Surrey. He had a studio at the new house that he used while writing what were later called his "Lambeth Books", which included The Song of Los in 1795. Like the others under the title, all aspects of the work, including the composition of the designs, the printing of them, the colouring of them, and the selling of them, happened at his home.[2] Early sketches for The Song of Los were included in a notebook that contained images were created between 1790 until 1793.[3] The Song of Los was one of the few works that Blake describes as "illuminated printing", one of his colour printed works with the coloured ink being placed on the copperplate before printed.[4]

The pages of the work and images were 23 cm × 17 cm (9.1 in × 6.7 in) in size, the size of America a Prophecy and Europe a Prophecy, and the work was occasionally bound together with the other two works.[5] Only six copies of the work survived, and the work was not listed along with Blake's other works that he sold in either 1818 or 1827. There were no mentions of the work by either Blake's contemporaries or his early biographer Alexander Gilchrist.[6]

Poem

[edit]- Scans of Copy E of The Song of Los currently held at the Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery[7]

The work begins with a title page image of an empty, dead world with an old man looking at the title of the work. The story of the work begins in Africa with Los singing of Adam, Noah, and Moses and how they were granted laws by Urizen. This involve abstractions being granted to Pythagoras, Socrates, and Plato, gospel being given to Jesus, a bible for Mahomet, and a book on war given to Odin. These caused the world to fail, as they were chains that bound the mind:[8]

Thus the terrible race of Los & Enitharmon gave

Laws & Religions to the sons of Har binding them more

And more to Earth: closing and restraining:

Till a Philosophy of Five Senses was complete

Urizen wept & gave it into the hands of Newton & Locke[9]— Plate 4, lines 13-17

In the second half of the work, Asia, Orc creates fire in the mind that causes kings to be startled and an apocalypse of sorts to start:

The Grave shrieks with delight, & shakes

Her hollow womb, & clasps the solid stem:

Her bosom swells with wild desire:

And mild & blood & glandous wine

In rivers rush & shout & dance,

On mountain, dale and plain.[10]— Plate 7, lines 35-40

Themes

[edit]The Song of Los is connected to both America and Europe in that it describes Africa and Asia, which operate as a sort of frame to the other works. As such, the three works are united by the same historical and social themes.[11] The "Africa" section of the poem summarizes Blake's historical cycles, which describes a three-part tyrannous power of Egypt, Babylon and Rome. Of this summary, the line "The Guardian Prince of Albion burns in his nightly tent" appears, which is also the first line of America a Prophecy. The section "Asia" follows the actions in America a Prophecy and describes a worldwide revolution in an apocalyptic state.[12] There are many similarities between the way Orc is described within the poem, a pillar of fire that burns oppression away, and how Fingal of Macpherson's Fingal is described. Fingal, in the Ossian work, is a good character that defends the oppressed against the Norse and the Romans. As Fingal fights imperialism, Orc fights against Urizen's rationality, and they both seek to free their people.[13]

The work closely follows the idea of biblical prophecy in that it is brief and concentrated. The first section condenses the history of religion, but does so in a non-chronological manner. His history relies on Urizen to establish the various historical moments as incidents, and the type of order within the poem is similar to the prophetic narrative.[14] The prophetic image is also embodied within the work by Los, who, when he submits to the system created by Urizen, loses his prophetic ability. In addition to the prophetic aspects, the work deals with religion as a whole. The first section describes the origin of priestcraft and the origins of religion, which is established through a bardic form of poetry.[15]

Critical response

[edit]Jon Mee claims that "Nowhere is Blake's interest in comparative religion more obvious than in The Song of Los".[16]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Bloom (1988). footnote. p. 905.

- ^ Bentley 2003 pp.122–124

- ^ Bentley 2003 p. 142

- ^ Bentley 2003 pp. 149

- ^ Bentley 2003 p. 154

- ^ Bentley 2003 p. 156

- ^ Morris Eaves; Robert N. Essick; Joseph Viscomi (eds.). "Index of " The Song of Los, copy E, 1795 (Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery)"". William Blake Archive. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ Bentley 2003 pp. 154–155

- ^ Erdman 1988 p. 68

- ^ Erdman 1988 pp. 69-70

- ^ Bentley 2003 p. 154

- ^ Frye 1990 pp. 215–216

- ^ Mee 2002 pp. 83–84

- ^ Mee 2002 pp. 24–25

- ^ Mee 2002 pp. 104, 122–123

- ^ Mee 2002 p. 122

References

[edit]- Bentley, G. E. (Jr). The Stranger From Paradise. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

- Damon, S. Foster. A Blake Dictionary. Hanover: University Press of New England, 1988.

- Erdman, David and Bloom, Harold. The Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. New York: Random House, 1988.

- Frye, Northrop. Fearful Symmetry. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.

- Mee, Jon. Dangerous Enthusiasm. Oxford: Clarendon, 2002.