The Right Stuff (film)

| The Right Stuff | |

|---|---|

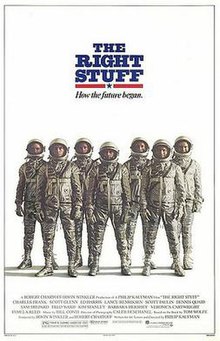

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Philip Kaufman |

| Written by | Philip Kaufman |

| Based on | The Right Stuff 1979 novel by Tom Wolfe |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Caleb Deschanel |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Bill Conti |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 192 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $27 million |

| Box office | $21.1 million (domestic only)[2] |

The Right Stuff is a 1983 American epic historical drama film written and directed by Philip Kaufman and based on the 1979 book of the same name by Tom Wolfe. The film follows the Navy, Marine, and Air Force test pilots who were involved in aeronautical research at Edwards Air Force Base, California, as well as the Mercury Seven, the seven military pilots who were selected to be the astronauts for Project Mercury, the first human spaceflight by the United States. The film stars Sam Shepard, Ed Harris, Scott Glenn, Fred Ward, Dennis Quaid, and Barbara Hershey; Levon Helm narrates and plays Air Force test pilot Jack Ridley.

The Right Stuff was a box-office bomb, grossing about $21 million (domestically) against a $27 million budget. Despite this, it received widespread critical acclaim, and was nominated for eight Oscars at the 56th Academy Awards, four of which it won. The film was a huge success on the home video market. In 2013, it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[3] The film was ranked #19 on the American Film Institute's most inspiring movies.

The film was later expanded into its titular franchise, including a television series and a documentary film.

Plot

[edit]In 1947, over the Muroc Army Air Field in California, a number of test pilots are killed while flying high-speed aircraft such as the rocket-powered Bell X-1. After another pilot, Slick Goodlin, demands $150,000 (equivalent to $2,047,000 in 2023) to attempt to break the sound barrier, war hero Captain Chuck Yeager receives the chance to fly the X-1. Yeager becomes the first person to fly at supersonic speed, defeating the "demon in the sky".

Six years later, Muroc, now Edwards Air Force Base, still attracts the best test pilots. Yeager (now a major) and friendly rival Scott Crossfield repeatedly break one another's speed records. They often visit the Happy Bottom Riding Club run by Pancho Barnes, who classifies the pilots at Edwards as either "prime" (such as Yeager and Crossfield) that fly the best equipment or newer "pudknockers" who only dream about it. Gordon "Gordo" Cooper, Virgil "Gus" Grissom and Donald "Deke" Slayton, captains of the United States Air Force, are among the "pudknockers" who hope to also prove that they have "the Right Stuff". The tests are no longer secret, as the military soon recognizes that it needs good publicity for funding. Cooper's wife, Trudy, and other wives are afraid of becoming widows, but cannot change their husbands' ambitions and desire for success and fame.

In 1957, the launch of the Soviet Sputnik satellite alarms the United States government. Politicians such as Senator Lyndon B. Johnson and military leaders demand that NASA help America defeat the Soviets in the new Space Race. The search for the first Americans in space excludes Yeager because he lacks a college degree. Grueling physical and mental tests select the Mercury Seven astronauts, including John Glenn of the United States Marine Corps, Alan Shepard, Walter Schirra and Scott Carpenter of the United States Navy, as well as Cooper, Grissom and Slayton; they immediately become national heroes. Although many early NASA rockets explode during launch, the ambitious astronauts all hope to be the first in space as part of Project Mercury. Although engineers see the men as passengers, the pilots insist that the Mercury spacecraft have a window, a hatch with explosive bolts, and pitch-yaw-roll controls. However, the Soviet Union beats them into space on April 12, 1961, with the launch of Vostok 1 carrying Yuri Gagarin. The seven astronauts are determined to match and surpass the Soviets.

Shepard is the first American to reach space on the 15-minute sub-orbital flight of Mercury-Redstone 3 on May 5. After Grissom's similar flight of Mercury-Redstone 4 on July 21, the capsule's hatch blows open and quickly fills with water. Grissom escapes, but the spacecraft, overweight with seawater, sinks. Many criticize Grissom for possibly panicking and opening the hatch prematurely. Glenn becomes the first American to orbit the Earth on Mercury-Atlas 6 on February 20, 1962, surviving a possibly loose heat shield, and receives a ticker-tape parade. He, his colleagues, and their families become celebrities, including a gigantic celebration in the Sam Houston Coliseum to announce the opening of the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, despite Glenn's wife Annie's fear of public speaking due to a stutter.

Although test pilots at Edwards mock the Mercury program for sending "spam in a can" into space, they recognize that they are no longer the fastest men on Earth, and Yeager states that "it takes a special kind of man to volunteer for a suicide mission, especially when it's on national TV." While testing the new Lockheed NF-104A, Yeager attempts to set a new altitude record at the edge of space but is nearly killed in a high-speed ejection when his engine fails. Though seriously burned after reaching the ground, Yeager gathers up his parachute and walks to the ambulance, proving his worth.

On May 15, 1963, Cooper has a successful launch on Mercury-Atlas 9, ending the Mercury program. As the last American to fly into space alone, he "went higher, farther, and faster than any other American ... for a brief moment, Gordo Cooper became the greatest pilot anyone had ever seen."

Cast

[edit]The following appeared as themselves in archive footage: Ed Sullivan with Bill Dana (in character as José Jiménez); Yuri Gagarin and Nikita Khrushchev embracing at a review, joined by Georgi Malenkov, Nikolai Bulganin, Kliment Voroshilov, and Anastas Mikoyan; Lyndon B. Johnson; John F. Kennedy; Alan Shepard (in Kennedy footage); and James E. Webb, director of NASA during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]In 1979, independent producers Robert Chartoff and Irwin Winkler outbid Universal Pictures for the movie rights to Tom Wolfe's book, paying $350,000.[4] They hired William Goldman to write the screenplay. Goldman wrote in his memoirs that his adaptation focused on the astronauts, entirely ignoring Chuck Yeager.[5] Goldman was inspired to accept the job because he wanted to say something patriotic about America in the wake of the Iran hostage crisis. Winkler writes in his memoirs that he was disappointed that Goldman's adaptation ignored Yeager.[6]

In June 1980, United Artists agreed to finance the film up to $20 million, and the producers began looking for a director. Michael Ritchie was originally attached but fell through; so did John Avildsen who, four years prior, had won an Oscar for his work under Winkler and Chartoff on the original Rocky. (The Right Stuff would have reunited Avildsen with both producers, and also with a fourth Rocky veteran, composer Bill Conti.)[7]

Ultimately, Chartoff and Winkler approached director Philip Kaufman, who agreed to make the film, but did not like Goldman's script; Kaufman disliked the emphasis on patriotism, and wanted Yeager put back in the film.[8] Eventually, Goldman quit the project in August 1980, and United Artists pulled out.

When Wolfe showed no interest in adapting his own book, Kaufman wrote a draft in eight weeks.[4] His draft restored Yeager to the story, because "if you're tracing how the future began, the future in space travel, it began really with Yeager and the world of the test pilots. The astronauts descended from them."[9]

After the financial failure of Heaven's Gate, the studio put The Right Stuff in turnaround. Then The Ladd Company stepped in with an estimated $17 million.

Casting

[edit]Actor Ed Harris auditioned twice in 1981 for the role of John Glenn. Originally, Kaufman wanted to use a troupe of contortionists to portray the press corps, but settled on the improvisational comedy troupe Fratelli Bologna, known for its sponsorship of "St. Stupid's Day" in San Francisco.[10] The director created a locust-like chatter to accompany the press corps whenever they appear, which was achieved through a sound combination of (among other things) motorized Nikon cameras and clicking beetles.[10]

Professional American football player Anthony Muñoz has a minor role in the film as a hospital orderly named Gonzales; the soft-spoken Muñoz was asked to lip sync his lines, and a "deeper, gruffer voice" was dubbed over him in post-production.[11]

Filming

[edit]Most of the film was shot in and around San Francisco between March and October 1982, with additional filming continuing into January 1983. A waterfront warehouse there was transformed into a studio.[4][Note 1] Location shooting took place primarily at the abandoned Hamilton Air Force Base north of San Francisco which was converted into a sound stage for the numerous interior sets.[12] No location could substitute for the distinctive Edwards Air Force Base landscape, so the entire production crew moved to the Mojave Desert to shoot the opening sequences that framed the story of the test pilots at Muroc Army Air Field, later Edwards AFB.[13] Additional shooting took place in California City in early 1983. During the filming of a sequence portraying Chuck Yeager's ejection from an NF-104,[14] stuntman Joseph Svec, a former Green Beret, was killed when he failed to open his parachute because he may have been unconscious from smoke.[15]

In 1982, the scene of the wives of the astronauts watching the television broadcast was filmed on military housing in Novato, California.

Yeager was hired as a technical consultant on the film. He took the actors flying, studied the storyboards and special effects, and pointed out the errors. To prepare for their roles, Kaufman gave the actors playing the seven astronauts an extensive videotape collection to study.[4]

The effort to make an authentic feature led to the use of many full-size aircraft, scale models and special effects to replicate the scenes at Edwards Air Force Base and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.[16] Special visual effects supervisor Gary Gutierrez said the first special effects were too clean for the desired "dirty, funky, early NASA look."[4] So Gutierrez and his team started from scratch, employing unconventional techniques, like going up a hill with model airplanes on wires and fog machines to create clouds, or shooting model F-104s from a crossbow device and capturing their flight with up to four cameras.[4] Avant garde filmmaker Jordan Belson created the background of the Earth as seen from high-flying planes and from orbiting spacecraft.[9]

Kaufman gave his five editors a list of documentary images he needed, sending them off to search for film from NASA, the Air Force and Bell Aircraft vaults.[4] They also discovered Russian stock footage not viewed in 30 years. During production, Kaufman met with resistance from the Ladd Company and threatened to quit several times. In December 1982, one reel of cut workprint of the film that included portions of John Glenn's flight disappeared from Kaufman's editing facility in San Francisco's Dogpatch neighborhood. The missing reel of cut workprint was never found, but was reconstructed using a black and white duplicate copy of the reel as a guide and reprinting new workprint from the original negative, which was always safely in storage at the film lab.

Historical accuracy

[edit]Although The Right Stuff was based on historic events and real people, some substantial dramatic liberties were taken. Neither Yeager's flight in the X-1 to break the sound barrier early in the film or his later, nearly fatal flight in the NF-104A were spur-of-moment, capriciously decided events, as the film seems to imply – they actually were part of the routine testing program for both aircraft. Yeager had already test-flown both aircraft a number of times previously and was very familiar with them.[17][18][19] Jack Ridley had actually died in 1957,[20] even though his character appears in several key scenes taking place after that, most notably including Yeager's 1963 flight of the NF-104A.

The Right Stuff depicts Cooper arriving at Edwards in 1953, reminiscing with Grissom there about the two of them having supposedly flown together at the Langley Air Force Base and then hanging out with Grissom and Slayton, including all three supposedly being present at Edwards when Scott Crossfield flew at Mach 2 in November 1953.[21] The film shows the three of them being recruited together there for the astronaut program in late 1957, with Grissom supposedly expressing keen interest in becoming a "star-voyager". According to their respective NASA biographies, none of the three was posted to Edwards before 1955 (Slayton in 1955[22] and Grissom and Cooper in 1956,[23][24]) and neither of the latter two had previously trained at Langley. By the time astronaut recruitment began in late 1957 after the Soviets had orbited Sputnik, Grissom had already left Edwards and returned to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, where he had served previously and was happy with his new assignment there. Grissom did not even know he was under consideration for the astronaut program until he received mysterious orders "out of the blue" to report to Washington in civilian clothing for what turned out to be a recruitment session for NASA.[23]

While the film took liberties with certain historical facts as part of "dramatic license", criticism focused on one: the portrayal of Gus Grissom panicking when his Liberty Bell 7 spacecraft sank following splashdown. Most historians, as well as engineers working for or with NASA and many of the related contractor agencies within the aerospace industry, are now convinced that the premature detonation of the spacecraft hatch's explosive bolts was caused by mechanical failure not associated with direct human error or deliberate detonation by Grissom.[Note 2] This determination had been made long before the film was completed.[25] Many astronauts, including Schirra, Cooper and Shepard, were critical of The Right Stuff for its treatment of Grissom,[26][27][28] who was killed in the Apollo 1 launch pad fire in January 1967 and thus unable to defend himself when the film was being made.

Other notable inaccuracies include: early termination of Glenn's flight after three orbits instead of seven (in reality, the flight was scheduled for at most three orbits); the engineers who built the Mercury craft are portrayed as Germans (in reality, they were mostly Americans).[9]

Film models

[edit]

A large number of film models were assembled for the production; for the more than 80 aircraft appearing in the film, static mock-ups and models were used as well as authentic aircraft of the period.[29] Lieutenant Colonel Duncan Wilmore, USAF (Ret) acted as the United States Air Force liaison to the production, beginning his role as a technical consultant in 1980 when the pre-production planning had begun. The first draft of the script in 1980 had concentrated only on the Mercury 7, but as subsequent revisions developed the treatment into more of the original story that Wolfe had envisioned, the aircraft of the late-1940s that would have been seen at Edwards AFB were required. Wilmore gathered World War II era "prop" aircraft including:

- Douglas A-26 Invader

- North American P-51 Mustang

- North American T-6 Texan and

- Boeing B-29 Superfortress

The first group were mainly "set dressing" on the ramp while the Confederate Air Force (now renamed the Commemorative Air Force) B-29 "Fifi" was modified to act as the B-29 "mothership" to carry the Bell X-1 and X-1A rocket-powered record-breakers.[30]

Other "real" aircraft included the early jet fighters and trainers as well as current USAF and United States Navy examples. These flying aircraft and helicopters included:

- Douglas A-4 Skyhawk

- LTV A-7 Corsair II

- North American F-86 Sabre

- Convair F-106 Delta Dart

- McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II

- Sikorsky H-34 Choctaw

- Sikorsky SH-3 Sea King

- Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star

- Northrop T-38 Talon[31]

A number of aircraft significant to the story had to be recreated. The first was an essentially static X-1 that had to at least roll along the ground and realistically "belch flame" by a simulated rocket blast from the exhaust pipes.[29] A series of wooden mock-up X-1s were used to depict interior shots of the cockpit, the mating up of the X-1 to a modified B-29 fuselage and bomb bay and ultimately to recreate flight in a combination of model work and live-action photography. The "follow-up" X-1A was also an all-wooden model.[30]

The U.S. Navy's Douglas D-558-2 Skyrocket that Crossfield duelled with Yeager's X-1 and X-1A was recreated from a modified Hawker Hunter jet fighter. The climactic flight of Yeager in a Lockheed NF-104A was originally to be made with a modified Lockheed F-104 Starfighter but ultimately, Wilmore decided that the production had to make do with a repainted Luftwaffe F-104G, which lacks the rocket engine of the NF-104.[30]

Wooden mock-ups of the Mercury space capsules also realistically depicted the NASA spacecraft and were built from the original mold.[9]

For many of the flying sequences, scale models were produced by USFX Studios and filmed outdoors in natural sunlight against the sky. Even off-the-shelf plastic scale models were utilized for aerial scenes. The X-1, F-104 and B-29 models were built in large numbers as a number of the more than 40 scale models were destroyed in the process of filming.[32] The blending together of miniatures, full-scale mock-ups and actual aircraft was seamlessly integrated into the live-action footage. The addition of original newsreel footage was used sparingly but to effect to provide another layer of authenticity.[33]

Reception and legacy

[edit]Box office

[edit]The Right Stuff had its world premiere on October 16, 1983, at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., to benefit the American Film Institute.[34][35] It was given a limited release on October 21, 1983, in 229 theaters, grossing $1.6 million on its opening weekend. It went into wide release on February 17, 1984, in 627 theaters where it grossed an additional $1.6 million on that weekend. Despite this, the movie bombed at the box office with $21.1 million (domestically). The failure of this and Twice Upon a Time caused The Ladd Company to shut down.

As part of the promotion for the film, Veronica Cartwright, Chuck Yeager, Gordon Cooper, Scott Glenn and Dennis Quaid appeared in 1983 at ConStellation, the 41st World Science Fiction Convention in Baltimore.[36]

Reviews

[edit]The Right Stuff received overwhelming acclaim from critics. The film holds a 96% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 52 reviews, with an average score of 8.80/10. The website's critical consensus reads: "The Right Stuff packs a lot of movie into its hefty running time, spinning a colorful, fact-based story out of consistently engaging characters in the midst of epochal events."[37] On Metacritic — which assigns a weighted mean score — the film has a score of 91 out of 100 based on 16 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[38]

Roger Ebert named The Right Stuff best film of 1983, writing: "There was a lot going on, and there's a lot going on in the movie, too.The Right Stuff is an adventure film, a special effects film, a social commentary and a satire... it joins a short list of recent American movies that might be called experimental epics: movies that have an ambitious reach through time and subject matter, that spend freely for locations or special effects, but that consider each scene as intently as an art film... It's a great film."[39] He later named it one of the best films of the decade, and wrote: "The Right Stuff is a greater film because it is not a straightforward historical account but pulls back to chronicle the transition from Yeager and other test pilots to a mighty public relations enterprise". He later put it at #2 on his 10 best of the 1980s, behind Martin Scorsese's Raging Bull.

Gene Siskel, Ebert's co-host of At the Movies, also named The Right Stuff the best film of 1983, and said: "It's a great film, and I hope everyone sees it."[40] Siskel also went on to include The Right Stuff at #3 on his list of the best films of the 1980s, behind Shoah and Raging Bull.[41]

In his review for Newsweek, David Ansen wrote: "When The Right Stuff takes to the skies, it can't be compared with any other movie, old or new: it's simply the most thrilling flight footage ever put on film".[4] Gary Arnold in his review for the Washington Post, wrote: "The movie is obviously so solid and appealing that it's bound to go through the roof commercially and keep on soaring for the next year or so".[35] In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby praised Shepard's performance: "Both as the character he plays and as an iconic screen presence, Mr. Shepard gives the film much well-needed heft. He is the center of gravity".[42]

Colin Greenland reviewed The Right Stuff for Imagine, and stated: "It is the film's willingness to question [...] idealism, while laying down some very fine footage of things that are moving very fast, which makes The Right Stuff thoroughly absorbing for nearly three and a quarter hours."[43]

Tom Wolfe made no secret of his dislike for the film, especially because of changes from his original book. William Goldman also disliked the choices made by Kaufman, writing in his 1983 book Adventures in the Screen Trade: "Phil [Kaufman]'s heart was with Yeager. And not only that, he felt the astronauts, rather than being heroic, were really minor leaguers, mechanical men of no particular quality, not great pilots at all, simply the product of hype."[44]

The Mercury Seven astronauts were mostly negative about the film. In an early interview, Deke Slayton said that none of the film "was all that accurate, but it was well done."[45] However, in his memoirs, Slayton described the film as being "as bad as the book was good, just a joke".[46] Wally Schirra liked the book a lot, but expressed disappointment and dislike for the movie, and he never forgave the producers for portraying Gus Grissom as a "bungling sort of coward", which was totally untrue.[47] In an interview, Schirra said: "It was the best book on space, but the movie was distorted and warped... All the astronauts hated [the movie]. We called it Animal House in Space."[48] In another interview, Schirra said: "They insulted the lovely people who talked us through the program - the NASA engineers. They made them like bumbling Germans".[45] Scott Carpenter said that it was a "great movie in all regards".[45] Alan Shepard harshly criticized both the movie and the book: "Neither Tom Wolfe nor [Philip Kaufman] had talked to any of the original seven guys, at any time... The Right Stuff [both the film and the book] is fiction... The movie assumed that Grissom had panicked, which wasn't true at all. The movie made him look like a bad guy for the whole movie. They were very hard on John Glenn's wife, who had a mild speech problem. They made Lyndon Johnson look like a clown. It was just totally fiction."[28]

Chuck Yeager said of his characterization: "Sam [Shepard] is not a real flamboyant actor, and I'm not a real flamboyant-type individual ... he played his role the way I fly airplanes".[4]

Robert Osborne, who introduced showings of the film on Turner Classic Movies, was quite enthusiastic about the film. The cameo appearance by the real Chuck Yeager in the film was a particular "treat", which Osborne cited. The recounting of many of the legendary aspects of Yeager's life was left in place, including the naming of the X-1, "Glamorous Glennis" after his wife and his superstitious preflight ritual of asking for a stick of Beemans chewing gum from his best friend, Jack Ridley.[Note 3]

Awards and nominations

[edit]Home media

[edit]On June 23, 2003, Warner Bros. Pictures released a two-disc DVD Special Edition that featured scene-specific commentaries with key cast and crew members, deleted scenes, three documentaries on the making of The Right Stuff including interviews with Mercury astronauts and Chuck Yeager, and a feature-length PBS documentary, John Glenn: American Hero. These extras are also included in the November 5, 2013 release of the 30th Anniversary edition, which also includes a 40-page book binding case, with the film in Blu-ray format. The extras are in standard DVD format.

In addition, the British Film Institute published a book on The Right Stuff by Tom Charity in October 1997 that offered a detailed analysis and behind-the-scenes anecdotes.

Soundtrack

[edit]Although an album mix had been prepared by Bill Conti in 1983 (and indeed the poster contains the credit "Original Soundtrack Available On Geffen Records"), the soundtrack album release was cancelled following the film's disappointing box office.[53] In 1986, Conti conducted a re-recording of selections from the score and from his music for North and South, performed by the London Symphony Orchestra and released by Varèse Sarabande[54] The original soundtrack was released by Varèse Sarabande on September 20, 2013, prepared from the 1983 album mix (as the original masters of the complete score were lost).[53]

| No. | Title | Artist | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Breaking The Sound Barrier" | Bill Conti | 4:46 |

| 2. | "Mach I" | Bill Conti | 1:23 |

| 3. | "Training Hard / Russian Moon" | Bill Conti | 2:17 |

| 4. | "Tango" | Bill Conti | 2:20 |

| 5. | "Mach II" | Bill Conti | 1:58 |

| 6. | "The Eyes Of Texas Are Upon You / The Yellow Rose Of Texas / Deep In The Heart Of Texas / Dixie" | Bill Conti | 2:50 |

| 7. | "Yeager and the F104" | Bill Conti | 2:26 |

| 8. | "Light This Candle" | Bill Conti | 2:45 |

| 9. | "Glenn's Flight" | Bill Conti | 5:08 |

| 10. | "Daybreak in Space" | Bill Conti | 2:48 |

| 11. | "Yeager's Triumph" | Bill Conti | 5:39 |

| 12. | "The Right Stuff (Single)" | Bill Conti | 3:11 |

| Total length: | 37:31[55] | ||

See also

[edit]- 1983 in film

- Ed Harris filmography

- Flight airspeed record

- History of post-WWII aviation

- Philip Kaufman filmography

- Sam Shepard filmography

- The Right Stuff (TV series)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Downtown San Francisco doubled for Lower Manhattan in the ticker-tape parade scene after John Glenn's return to Earth. The scene was shot at the intersection of California and Montgomery Streets in the Financial District, and the Pacific Stock Exchange on the corner of Sansome and Pine Streets can be spotted doubling for the New York Stock Exchange in the final part of the scene.[4]

- ^ Schirra proved that activating the hatch explosives would have left a large welt on any part of the body that came in contact with the trigger. He proved this on his Mercury flight when he intentionally blew the hatch on October 3, 1962 when his spacecraft was on the deck of the recovery carrier.[25]

- ^ This allusion to Beemans chewing gum was later included in The Rocketeer (1991).

References

[edit]- ^ The Right Stuff". Columbia-EMI Warner. British Board of Film Classification, November 29, 1983, Retrieved: October 16, 2013. Archived 2013-10-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Right Stuff at Box Office Mojo

- ^ "Library of Congress announces 2013 National Film Registry selections" (Press release). Archived 2016-06-10 at the Wayback Machine Washington Post, December 18, 2013. Retrieved: December 18, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ansen, David and Katrine Ames. "A Movie with All 'The Right Stuff'." Newsweek, October 3, 1983, p. 38.

- ^ Goldman 2001, p. 254.

- ^ Winkler, Irwin (2019). A Life in Movies: Stories from Fifty Years in Hollywood (Kindle ed.). Abrams Press. p. 1717/3917.

- ^ Goldman 2001, p 257.

- ^ Goldman 2001, p. 258.

- ^ a b c d Wilford, John Noble. "'The Right Stuff': From Space to Screen." Archived 2020-11-15 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, October 16, 1983. Retrieved: December 29, 2008.

- ^ a b Williams, Christian. "A Story that Pledges Allegiance to Drama and Entertainment." Washington Post, October 20, 1983, A18.

- ^ Newhan, Ross (November 13, 1985). "His Faith Produced Miracles : Munoz Needed It to Come Back and Excel in the NFL". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Farmer 1984, p. 34.

- ^ Farmer 1984, p. 41.

- ^ Note that Yeager's ejection was from the highly specialized NF-104 rocket jet, while the movie used a common unmodified F-104.

- ^ "Svec's Freefall, Check-Six.com". Archived from the original on 2016-08-18. Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- ^ Farmer 1983, p. 47.

- ^ Young, Dr. James.. "Mach Buster." Archived 2020-11-15 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Flight Test Center History Office, 2014. Retrieved: July 14, 2014.

- ^ "Chuck Yeager, in his our words, regarding his experience with the NF-104." Archived 2020-11-15 at the Wayback Machine Check-six.com, April 23, 2014. Retrieved: July 14, 2014.

- ^ Complete Video: Then Col. Chuck Yeager Crash In NF-104A Dec 10, 1963 At Edwards Air Force Base , Photography Branch Edwards Air Force Base, December 10, 1963, uploaded to YouTube by Edwards Air Force Base December 10, 2019.

- ^ "Jack Ridley." Archived 2020-11-15 at the Wayback Machine Nasa September 18, 1997. Retrieved: July 14, 2014.

- ^ "Famed aviator Scott Crossfield dies in plane crash." Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine The Seattle Times, April 19, 2006.

- ^ Gray, Tara. "Donald K. 'Deke' Slayton". Archived 2020-11-15 at the Wayback Machine NASA. Retrieved: July 14, 2014.

- ^ a b Zornio, Mary C. Virgil Ivan 'Gus' Grissom." Archived 2020-11-15 at the Wayback Machine NASA. Retrieved: July 14, 2014.

- ^ Gray, Tara. "L. Gordon Cooper, Jr." Archived 2020-11-15 at the Wayback Machine NASA. Retrieved: July 14, 2014.

- ^ a b Buckbee and Schirra 2005, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Buckbee and Schirra 2005, p. 72.

- ^ Cooper 2000, p. 33.

- ^ a b Alan Shepard's Interview to Charlie Rose, July 20, 1994.

- ^ a b Farmer 1983, p. 49.

- ^ a b c Farmer 1983, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Farmer 1983, p. 51.

- ^ Farmer 1984, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Farmer 1984, p. 66.

- ^ Morganthau, Tom and Richard Manning. "Glenn Meets the Dream Machine." Newsweek, October 3, 1983, p. 36.

- ^ a b Arnold, Gary. "The Stuff of Dreams." Washington Post, October 16, 1983, p. G1.

- ^ "1983 World Science Fiction Convention." Archived 2020-11-15 at the Wayback Machine fanac.org, 2012. Retrieved: September 5, 2012.

- ^ "The Right Stuff". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on February 21, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ "The Right Stuff Reviews". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1983). "The Right Stuff". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (December 25, 1983). "Movie year 1983: Box office was better than the films". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ "At the Movies-Best of 1983." Archived 2013-05-07 at the Wayback Machine Youtube. Retrieved: May 14, 2013.

- ^ Kael, Pauline. "The Sevens". The New Yorker, October 17, 1983.

- ^ Greenland, Colin (June 1984). "Fantasy Media". Imagine (review) (15). TSR Hobbies (UK), Ltd.: 43.

- ^ Goldman, William (1989). Adventures in the Screen Trade: A Personal View of Hollywood and Screenwriting (reissue ed.). Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 0-446-39117-4.

- ^ a b c Bumiller, Elisabeth and Phil McCombs. "The Premiere: A Weekend Full of American Heroes and American Hype." Washington Post, October 17, 1983, p. B1.

- ^ Slayton 1994, p. 317.

- ^ Colin Burgess, Sigma 7: The Six Mercury Orbits of Walter M. Schirra, Jr., Springer Praxis Books, 2016.

- ^ Vernon Scott, article "Schirra debunks notions about astronauts," The Tribune newspaper, San Diego, CA, 9 May 1985, p. D-12.

- ^ "The 56th Academy Awards (1984) Nominees and Winners." Archived 2017-11-02 at the Wayback Machine oscars.org. Retrieved: October 10, 2011.

- ^ "'The Right Stuff'." Archived 2020-11-15 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times. Retrieved: January 1, 2009.

- ^ "1984 Hugo Awards." Archived 2007-12-25 at the Wayback Machine thehugoawards.org. Retrieved: September 5, 2012.

- ^ "AFI's 100 YEARS…100 CHEERS". American Film Institute. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ a b Liner notes, The Right Stuff Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, VCL 0609 1095

- ^ "The Right Stuff/North and South." Archived 2020-11-15 at the Wayback Machine AllMusic. Retrieved: July 15, 2015.

- ^ "The Right Stuff Soundtrack." Archived 2020-11-15 at the Wayback Machine AllMusic. Retrieved: February 2, 2014.

Bibliography

[edit]- Buckbee, Ed and Walter Schirra. The Real Space Cowboys. Archived 2012-02-09 at the Wayback Machine Burlington, Ontario: Apogee Books, 2005. ISBN 1-894959-21-3.

- Charity, Tom. The Right Stuff (BFI Modern Classics). London: British Film Institute, 1991. ISBN 0-85170-624-X.

- Conti, Bill (with London Symphony Orchestra). The Right Stuff: Symphonic Suite; North and South: Symphonic Suite. North Hollywood, California: Varèse Sarabande, 1986 (WorldCat) Archived 2008-12-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- Cooper, Gordon. Leap of Faith. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2000. ISBN 0-06-019416-2.

- Farmer, Jim. "Filming the Right Stuff." Air Classics, Part One: Vol. 19, No. 12, December 1983, Part Two: Vol. 20, No. 1, January 1984.

- Glenn, John. John Glenn: A Memoir. New York: Bantam, 1999. ISBN 0-553-11074-8.

- Goldman, William. Which Lie Did I Tell?: More Adventures in the Screen Trade. New York: Vintage Books USA, 2001. ISBN 0-375-70319-5.

- Hansen, James R. First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. ISBN 0-7432-5631-X.

- Wolfe, Tom. The Right Stuff. New York: Bantam, 2001. ISBN 0-553-38135-0.

- Slayton, Deke and Michael Cassutt. Deke! U.S. Manned Space: From Mercury to the Shuttle. New York: Tom Doherty Associates, 1994. ISBN 0-312-85503-6.

External links

[edit]- 1983 films

- 1983 drama films

- 1980s American films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s historical drama films

- American aviation films

- American films based on actual events

- American historical drama films

- American space adventure films

- Cold War aviation films

- Cultural depictions of Dwight D. Eisenhower

- English-language historical drama films

- Films about astronauts

- Films about NASA

- Films about test pilots

- Films about the United States Air Force

- Films about the United States Marine Corps

- Films about the United States Navy

- Films adapted into television shows

- Films based on non-fiction books

- Films based on works by Tom Wolfe

- Films directed by Philip Kaufman

- Films produced by Irwin Winkler

- Films produced by Robert Chartoff

- Films scored by Bill Conti

- Films set in California

- Films set in 1947

- Films set in 1953

- Films set in 1957

- Films set in 1959

- Films set in 1961

- Films set in 1962

- Films set in 1963

- Films shot in San Francisco

- Films that won the Best Original Score Academy Award

- Films that won the Best Sound Editing Academy Award

- Films that won the Best Sound Mixing Academy Award

- Films whose editor won the Best Film Editing Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Philip Kaufman

- Project Mercury

- Science docudramas

- The Ladd Company films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Warner Bros. films

- Scott Carpenter

- Gordon Cooper

- John Glenn

- Gus Grissom

- Wally Schirra

- Alan Shepard

- Deke Slayton