Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers

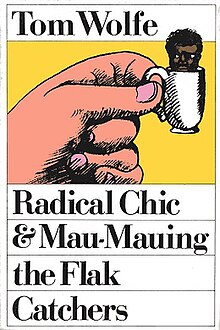

Cover of the first edition | |

| Author | Tom Wolfe |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | New Journalism |

| Publisher | Farrar, Straus & Giroux |

Publication date | 1970 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 153 |

| ISBN | 0-553-14444-8 |

| OCLC | 219920390 |

Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers is a 1970 book by Tom Wolfe. The book, Wolfe's fourth, is composed of two essays: "These Radical Chic Evenings", first published in June 1970 in New York magazine, about a gathering Leonard Bernstein held for the Black Panther Party, and "Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers", about the response of many minorities to San Francisco's poverty programs. Both essays looked at the conflict between black rage and white guilt.[1]

"Radical Chic"

[edit]The first piece is set in the duplex on Park Avenue in Manhattan inhabited by conductor Leonard Bernstein, his wife the actress Felicia Cohn Montealegre, and their three children. Bernstein assembled many of his wealthy socialite friends to meet with representatives of the Black Panthers and discuss ways to help their cause.[2] The party was a typical affair for Bernstein, a longtime Democrat, who was known for hosting civil rights leaders at such parties.[3]

The Bernsteins' usual staff of white South Americans served the party.[4] Some of the Bernsteins' typical friends in the arts and guests in journalism (including Oscar-nominated director Otto Preminger and television reporter Barbara Walters) are labeled the "radical chic," as Wolfe characterizes them as pursuing radical ends for social reasons, partially because organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People had become mainstream.[1] Wolfe's satire is implicitly a criticism of the general phenomenon of white guilt and armchair agitation becoming facets of high fashion.[5]

When Time magazine later interviewed a minister of the Black Panthers about Bernstein's party, the official said of Wolfe: "You mean that dirty, blatant, lying, racist dog who wrote that fascist disgusting thing in New York magazine?"[1]

"Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers"

[edit]The second part of Wolfe's book is set at the Office of Economic Opportunity in San Francisco, which was in charge of administering many of the anti-poverty programs of the time. Wolfe presents the office as corrupt, continually gamed by hustlers diverting cash into their own pockets. The essay centers on the irony of these failed programs fortifying not the diets but the resentment and contempt of the black, Chicano, Filipino, Chinese, Indian, and Samoan populations of San Francisco.[2]

Wolfe describes hapless city bureaucrats, the Flak Catchers, whose function has been reduced to taking abuse, or "mau-mauing" (in reference to the intimidation tactics employed in Kenya's anti-colonial Mau Mau Uprising), from militant young blacks and Samoans, who are depicted as reveling in the newfound vulnerability of "the Man". The Flak Catchers smile pathetically, allowing their tormentors to indulge themselves in abuse; the process is seen as a farcical but useful expedient, condescending toward the resentment of these communities. Wolfe describes one mau-mauer who would show up at the offices and hand over icepicks, switchblades and straight razors that he said were taken from gangs, in exchange for payments from the program. As a result, much of the money of these programs was not reaching its intended recipients, rendering the programs largely ineffective.[1]

Cultural impact

[edit]The phrase "radical chic" has entered into the political and cultural lexicon to describe the adoption of radical or quasi-radical causes by members of the wealthy high-society and celebrity class.[3] Both essays were later reprinted in Wolfe's collection The Purple Decades, indicating that he considered them among his best work.[5][6]

"Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers" is cited in David Foster Wallace's essay on "Joseph Frank's Dostoevsky", published in Consider the Lobster. Wallace recommends reading it comparatively with Dostoevsky's own account in House of the Dead to understand Dostoevsky's disillusionment as a young rich socialist when he met the dregs of Tsarist Russian society in prison camp.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Foote, Timothy (December 21, 1970). "Books: Fish in the Brandy Snifter". Time.

- ^ a b "Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers". Tomwolfe.com. Archived from the original on 2005-09-01. Retrieved 2007-07-22.

- ^ a b Donal Henahan (1990-10-15). "Leonard Bernstein, 72, Music's Monarch, Dies". The New York Times.

- ^ Lasch-Quinn, Elisabeth (1999). "How to Behave Sensitively: Prescriptions for Interracial Conduct from the 1960s to the 1990s". Journal of Social History. 33 (2): 409–427. doi:10.1353/jsh.1999.0064.

- ^ a b "Cry Wolfe; The Purple Decades by Tom Wolfe". Financial Times. 1983-04-09.

- ^ Jonathan Yardley (1982-11-07). "Tom Wolfe and His Dissecting Pen". The Washington Post.

- ^ David Foster Wallace (April 9, 1996). "Feodor's Guide: Joseph Frank's Dostoevsky". The Village Voice. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

If you want to get some idea of how Dostoevskian irony might translate into modern U.S. culture, try reading House of the Dead and Tom Wolfe's "Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers" at the same time.

External links

[edit]- "Radical Chic", the complete text—New York magazine

- "Radical Chic", a scan of the original article—New York magazine