The Rainbow (1989 film)

| The Rainbow | |

|---|---|

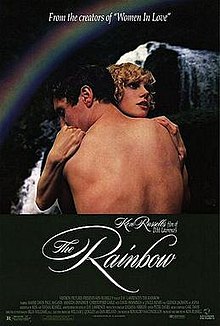

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ken Russell |

| Written by | D. H. Lawrence Ken Russell Vivian Russell |

| Produced by | Dan Ireland William J. Quigley |

| Starring | Sammi Davis Paul McGann Amanda Donohoe |

| Cinematography | Billy Williams |

| Edited by | Peter Davies |

| Music by | Carl Davis |

| Distributed by | Vestron Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 113 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5 million[1] |

| Box office | £100,856 (UK)[2] |

The Rainbow is a 1989 British drama film co-written and directed by Ken Russell[3] and adapted from the D. H. Lawrence novel The Rainbow (1915). Sammi Davis stars as Ursula, a sheltered young pupil, then schoolteacher, who is taken under the wing (sexually and otherwise) by the more sophisticated Winifred (Amanda Donohoe).

Russell's film was a companion to his 1969 adaption of Lawrence's second novel about the Brangwen sisters Women in Love (1920). Glenda Jackson appears as the mother of the character she played in Women in Love (1969). The film was entered into the 16th Moscow International Film Festival.[4]

Plot

[edit]Set during the final years of England's Victorian era, Ursula Brangwen is the eldest of several children of wealthy Derbyshire farmer Will Brangwen and his wife Anna. Since the age of 3, Ursula has had a fascination with rainbows, and after one rainstorm, she runs off with a suitcase hoping to look for a pot of gold at the end of it. Will tries to ease her fascination by making her a jam sandwich with several spreads of different flavoured jam resembling a rainbow.

During her teenage years, Ursula falls into a same-sex romance with her older swimming and gym teacher Winifred Inger, while at the same time, Ursula also begins having romantic feelings for Anton Skrebensky, a student at the nearby boys' high school who plans to enlist in the Army after graduation. Ursula and Winifred spend romantic weekends together at Winifred's house as well as hiking in the hills around the area. Winifred introduces Ursula to an artist friend of hers who encourages Ursula to model in the nude for his paintings, but she is thrown out after she refuses his sexual advances and demands her pay.

One weekend, Ursula brings along Winifred as her chaperone when she visits her father's wealthy older brother, Uncle Henry, who becomes smitten with Winifred and, after a short courtship, proposes marriage to her. Winifred accepts which creates jealousy in Ursula.

Feeling abandoned and alone after Winifred leaves her to marry Uncle Henry, and Anton goes off to fight in the Second Boer War in South Africa, Ursula decides to restart her life by becoming a schoolteacher. After graduation from high school, Ursula moves to London where she takes a job as a schoolmarm at a poor elementary school in the East End, where she becomes quickly appalled by the lack of discipline and hygiene among the impoverished children she is forced to teach (many of whom are illiterate child laborers). She also fends off sexual advances by the lecherous headmaster of the school, who uses physical discipline to settle unruly students. Ursula initially refuses to go to that level of physical punishment for her class. However, after being provoked a few too many times by one belligerent boy who uses a slingshot to pelt her with small stones, Ursula finally loses her temper and violently beats the child with a cane in full view of the class and school staff. While her violent outburst actually pacifies her students, and makes the headmaster stop making inappropriate passes at her, Ursula is guilt-ridden by her own actions and as a result, she quits her job when the school year ends.

Returning to her family farm a year-and-a-half later in the spring of 1901, Ursula is reunited with Anton who is back from war and wants to rekindle a romance with her. After having a casual reunion with Winifred, who is married to Uncle Henry and now has a baby, Ursula decides to consummate her romance with Anton. At the same time, Ursula also begins working with a local miners' union to help out unprivileged workers with salary and securities. When she learns that she may be pregnant, Anton proposes marriage to her, but she turns him down, wanting to follow her own path in life.

After Ursula learns that she is not pregnant, Anton leaves her for good. One day, Ursula is attacked while walking home alone by two mine workers who attempt to rape her, but she escapes and spends most of the day hiding out in a rain-soaked forest, but she makes it back to her farm. There she finds a telegram from Anton, who informs her he married another woman and has left the country with her for a military post in India.

After a heartfelt talk with her father about life and what path it leads in life, Ursula decides to start all over again by taking another teaching position in a new town about two hours away. In the final scene, Ursula packs a suitcase and runs out of her house to chase another large rainbow that appears after a storm, just like her younger self used to in the opening scene.

Cast

[edit]- Sammi Davis as Ursula Brangwen

- Paul McGann as Anton Skrebensky

- Amanda Donohoe as Winifred Inger

- Christopher Gable as Will Brangwen

- David Hemmings as Uncle Henry

- Glenda Jackson as Anna Brangwen

- Dudley Sutton as MacAllister

- Jim Carter as Mr. Harby

- Judith Paris as Miss Harby

- Kenneth Colley as Mr. Brunt

- Glenda McKay as Gudrun Brangwen

- Mark Owen as Jim Richards

- Ralph Nossek as Vicar

- Nicola Stephenson as Ethel

- Molly Russell as Molly Brangwen

- Alan Edmondson as Billy Brangwen

- Rupert Russell as Rupert Brangwen

- Richard Platt as Chauffeur

- Bernard Latham as Uncle Alfred

- John Tams as Uncle Frank

- Zoe Brown as Ursula (aged 3)

- Amy Evans as Baby Gudrun

- Sam McMullen as Winifred's baby

Production

[edit]Russell wrote the script in the late 1970s after making Clouds of Glory (1978) for television. He collaborated with Viv Russell and felt it would be a relatively easy film to finance because Women in Love had been such a success.[5] Russell said he was "well pleased" with the script "mainly due to Viv's contribution."[6]

He focused on the last third of the novel, the story of Ursula. Russell called it "a timeless parable...about a girl who won't stay within the comforting womb of her family but goes off alone to find her own way in life...This film's about saying no I won't because I'm me and not you. And it's about a woman saying that in the days they weren't supposed to."[7]

"It's the same heroines," Russell said, "but they're in their teens rather than in their 20s. It's them growing up and battling all the things that females of all ages have had to do throughout history."[8]

Russell was optimistic about getting money. "I was back on home ground in Lawrence country. There was nude wrestling (a man and a woman this time) and stampeding animals (shire horses this time) all that lovely scenery and the usual horny miners."[9]

However, all the major studios in Hollywood passed. So too did David Puttnam, who Russell said thought the script was a "downer" and that Ursula was a "pain in the arse". Puttnam did say he would recommend it to Goldcrest Films, but the director heard nothing further from him.[10]

In 1983, it was reported that Russell had taken an option on the novel.[11] In January 1984, Russell said he was unable to get finance for the film. "It seems to me that as the last one did well commercially this would too. But I just can't sell it anywhere. Everyone says 'it's a beautiful script but it's not commercial.' Of course they'd be saying exactly the same thing about Women in Love if I were trying to sell that now. It's so hard to find anyone with the courage to say yes to anything today."[12]

In April 1987, Russell said he "had no luck with" raising funding for The Rainbow, though he was hopeful to make a movie of a Lawrence novella, St Mawr.[13]

However, Russell's film Gothic (1986) became a big success on video, and Vestron told Dan Ireland that if Russell could come up with a horror movie, they would finance The Rainbow. He signed a three-picture deal with Vestron that included Salome's Last Dance, Lair of the White Worm and The Rainbow.[14]

Russell says the film was budgeted at £2.5 million, but Vestron insisted he lose half a million from the budget. He rewrote the script to lose a dream sequence and a crowd sequence and decided to shoot the film in London and not the Lake District as originally planned. Russell later wrote these changes did not compromise the film: indeed, he felt they tightened the script.[15]

Vestron wanted names: they hoped Glenda Jackson would play the mother of one of the characters in Women in Love but she was on Broadway at the time. Russell offered the part to Julie Christie, who turned it down. Vestron wanted Doug Savant to play the English officer, but Russell did not think he was suitable. Russell wanted to work with Amanda Donohoe again, but Vestron pressed for a name; Kelly McGillis, Mariel Hemingway and Theresa Russell turned it down, while Catherine Oxenberg would not appear nude. Vestron agreed to Sammi Davis in the lead, as they had liked her in Lair of the White Worm. Charles Dance and Jeremy Irons turned down the role of Davis' father, enabling Russell to cast Christopher Gable.[16]

Russell said Davis "has exactly the same characteristics as the young Glenda Jackson: a totally instinctive ability to identify with the character she is playing, an emotional directness and that undefinable quality that makes the camera love her."[1]

Russell later said the character of Ursula was "a bit of a problem to bring off because she's a young woman who is fighting hard for her identity and she could be seen as grumbling all the time...but Sammi transcends all that."[7]

Vestron refused to green light to film without names. Viv suggested Elton John, who wanted to try acting, and he was sent a copy of the script. In June 1988, it was announced Elton John was to play Uncle Harry.[17] Glenda Jackson was able to make the movie and this led to Vestron agreeing to finance it.[18]

Filming started in July. The film was shot in London, Oxfordshire and the Lake District over seven weeks.[7]

During filming, John bowed out for "personal reasons".[19] Russell offered the role to Alan Bates and Oliver Reed, who both turned it down before David Hemmings accepted.[20]

Producer Ronaldo Vasconcellos called it "one of Ken's calmer films and I think the world is ready for it."[7]

The film came out a few months after a British TV version of the novel, which had a bigger budget. Davis had auditioned for the lead, but been turned down in favour of Imogen Stubbs.[7]

Sammi Davis said "Ken couldn't be normal. But he's the best director I ever worked with: full of energy, a brilliant sense of humor. And very demonstrative, not wordy-which I like, 'cause I'm not a wordy person. The reason people probably think he's crazy is because of his films. He picks such odd subjects."[21]

Davis appeared in the film naked in a few scenes. "Up till then I'd always said no," she says. "But (nudity) was so essential to this part. That's what Lawrence is about: nakedness, physically and mentally getting down to the core of the person. That's why I felt fine about doing it."[21]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Billington, Michael (30 April 1989). "Sammi Davis: Just Right for D.H. Lawrence: Like the heroine of 'The Rainbow,' the British actress needed to find escape and fulfillment. Sammi Davis on the Rise". New York Times. p. H17.

- ^ "Back to the Future: The Fall and Rise of the British Film Industry in the 1980s - An Information Briefing" (PDF). British Film Institute. 2005. p. 28.

- ^ James, Caryn (2007). "NY Times: The Rainbow". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- ^ "16th Moscow International Film Festival (1989)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 16 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ Russell p. 157

- ^ Russell p. 164

- ^ a b c d e Malcolm, Derek (18 August 1988). "Rainbow warrior: After twenty years Ken Russell films Lawrence again". The Guardian. p. 23.

- ^ At the Movies: [Review] Lawrence Van Gelder. New York Times 6 May 1988: C.8.

- ^ Russell p. 195

- ^ Russell p. 168

- ^ THE NUCLEAR "AFTERMATH" Welsh, James M. Literature/Film Quarterly; Salisbury Vol. 11, Iss. 4, (1983): 277.

- ^ MOVIES: KEN RUSSELL: OPERA HIGHS AFTER FILM LOWS Mann, Roderick. Los Angeles Times 22 January 1984: r14.

- ^ WHERE RUSSELL DIRECTS, CONTROVERSY FOLLOWS: [Home Edition] Mann, Roderick. Los Angeles Times 19 April 1987: 29.

- ^ Melville, Marty (15 May 2012). "Dan Ireland on The Lair of the White Worm". The Trailers From Hell! Blog. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ Russell p. 292-293

- ^ Russell p. 292-294

- ^ FIRE UP! . . .: [FINAL EDITION, C] Kathy O'Malley & Hanke Gratteau. Chicago Tribune 26 June 1988: 2.

- ^ Russell p. 296

- ^ PECKING ORDER, PART 2 . . Chicago Tribune 2 August 1988: 14.

- ^ Russell p. 305-306

- ^ a b Riding a `Rainbow': [Home Edition] ARKATOV, JANICE. Los Angeles Times 20 May 1989: 2.

External links

[edit]- The Rainbow at IMDb

- 1989 films

- 1989 drama films

- 1989 LGBTQ-related films

- 1980s British films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s historical drama films

- British historical drama films

- British LGBTQ-related films

- Films about female bisexuality

- Films based on British novels

- Films based on works by D. H. Lawrence

- Films directed by Ken Russell

- Films scored by Carl Davis

- Films set in the 1910s

- Lesbian-related films

- 1980s LGBTQ-related drama films

- Vestron Pictures films

- English-language historical drama films