March of Progress

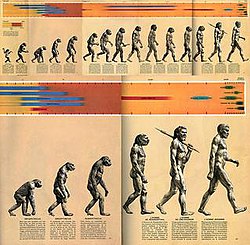

The March of Progress,[1][2][3] originally titled The Road to Homo Sapiens, is an illustration that presents 25 million years of human evolution. It was created for the Early Man volume of the Life Nature Library, published in 1965, and drawn by the artist Rudolph Zallinger. It has been widely parodied and imitated to create images of progress of other kinds.

Illustration

[edit]Context

[edit]The illustration is part of a section of text and images commissioned by Time-Life Books for the Early Man volume (1965) of the Life Nature Library, by F. Clark Howell.[4]

The illustration is a foldout entitled "The Road to Homo Sapiens". It shows a sequence of figures, drawn by natural history painter and muralist Rudolph Zallinger (1919–1995).[4] The 15 human evolutionary forebears are lined up as if they were marching in a parade from left to right. The first two sentences of the caption read "What were the stages of man's long march from apelike ancestors to sapiens? Beginning at right and progressing across four more pages are milestones of primate and human evolution as scientists know them today, pieced together from the fragmentary fossil evidence."[4]

Sequence of species

[edit]The 15 primate figures in Zallinger's image, from left to right, are listed below. The datings follow the original graphic and may no longer reflect current scientific opinion.

- Pliopithecus, 22–12 million year old "ancestor of the gibbon line"

- Proconsul, 21–9 million year old primate which may or may not have qualified as an ape

- Dryopithecus, 15–8 million year old fossil ape, the first such found (1856) and probable ancestor of modern apes

- Oreopithecus, 15–8 million years old

- Ramapithecus, 13–8 million year old ape and possible ancestor of modern orangutans (now considered a female Sivapithecus)

- Australopithecus, 2–3 million years old; then considered the earliest "certain hominid"

- Paranthropus, 1.8–0.8 million years old

- Advanced Australopithecus Homohabilis, 1.8–0.7 million year old

- Homo erectus, 700,000–400,000 years old, then the earliest known member of the genus Homo

- Early Homo sapiens, 300,000–200,000 years old; from Swanscombe, Steinheim and Montmaurin, then considered probably the earliest H. sapiens

- Solo Man, 100,000–50,000 years old; described as an extinct Asian "race" of H. sapiens (now considered a sub-species of H. erectus)

- Rhodesian Man, 50,000–30,000 years old; described as an extinct African "race" of H. sapiens (now considered either H. rhodesiensis or H. heidelbergensis and dated much earlier)

- Neanderthal Man, 100,000–40,000 years old

- Cro-Magnon Man, 40,000–5,000 years old

- Modern Man, 40,000 years to the present

Intention

[edit]Contrary to appearances and some complaints, the original 1965 text of "The Road to Homo Sapiens" reveals an understanding of the fact that a linear presentation of a sequence of primate species, all in the direct line of human ancestors, would not be a correct interpretation. For example, the fourth of Zallinger's figures (Oreopithecus) is said to be "a likely side branch on man's family tree". Only the next figure (Ramapithecus) is described as "now thought by some experts to be the oldest of man's ancestors in a direct line" (something no longer considered likely). That implies that the first four primates are not to be considered actual human ancestors. Likewise, the seventh figure (Paranthropus) is said to be "an evolutionary dead end".[4] In addition, the colored stripes, across the top of the figure, which indicate the age and duration of the various lineages clearly imply that there is no evidence of direct continuity between extinct and extant lineages and also, multiple lineages of the figured hominids occurred contemporaneously at several points in the history of the group.

Reception

[edit]

The image has frequently been copied, modified, and parodied.

It has also been criticized as "unintentionally and wrongly" implying that "evolution is progressive".[5] The image has been described as having a "visual logic" of linear progression.[1] The Lancet called it "proverbial, much quoted or adapted, familiar to multitudes who have never seen its original version or heard of its maker".[2] The image has become better-known than the science behind it.[3]

With regard to the way the illustration has been interpreted, the anthropologist and author of the section, F. Clark Howell, remarked:[6]

The artist didn't intend to reduce the evolution of man to a linear sequence, but it was read that way by viewers. ... The graphic overwhelmed the text. It was so powerful and emotional.[6]

Stephen Jay Gould (1941–2002) condemned the iconology of the image in several pages of his 1989 book, Wonderful Life, reproducing several advertisements and political cartoons that make use of the illustration to make their various points. In a chapter, "The Iconography of an Expectation", he asserted that[7]

The march of progress is the canonical representation of evolution – the one picture immediately grasped and viscerally understood by all. ... The straitjacket of linear advance goes beyond iconography to the definition of evolution: the word itself becomes a synonym for progress. ... [But] life is a copiously branching bush, continually pruned by the grim reaper of extinction, not a ladder of predictable progress.[7]

The intelligent design advocate Jonathan Wells wrote in Icons of Evolution: Science or Myth? (2002), "Although it is widely used to show that we are just animals, and that our very existence is a mere accident, the ultimate icon goes far beyond the evidence."[8] The book likens a selection of evolution theory textbook topics to the cover illustration thus qualified.

Riley Black, writing for Scientific American, argues that the idea of a "march of progress", as depicted in the 1965 Time-Life illustration, dates back to the medieval great chain of being and the 19th century idea of the "missing link" in the fossil record. In her view, to understand life and evolution, "step one involves casting out types of imagery which constrain rather than enlighten."[9] Writing in Wired, Black added that "There is perhaps no other illustration that is as immediately recognizable as representing evolution, but the tragedy of this is that it conveys a view of life that does not resemble our present understanding of life's history."[10]

Parodies and adaptations

[edit]The March of Progress has often been imitated, parodied, or adapted for commercial or political purposes.[7] The cover of the 1972 Doors album Full Circle references the March of Progress, as does the 1985 Supertramp album Brother Where You Bound, while the soundtrack CD for the 1992 movie Encino Man shows an ape evolving into a skateboarder.[11] The December 2005 issue of The Economist depicts hominids progressing up a flight of stairs to transform into a woman in a black dress holding a glass of champagne to illustrate "The Story of Man".[12] British rapper, Digga D, adapted a version of the image for the cover of his third mixtape, Noughty by Nature.[13] The game Yume 2kki also has an "Event" which takes place in an area called "Chess World," the Event starts off by walking through a corridor similar to another location in the game, after the corridor ends, you are taken to a singular room with a throne, sitting on this throne will then teleport you to the Event.[14]

Predecessors

[edit]

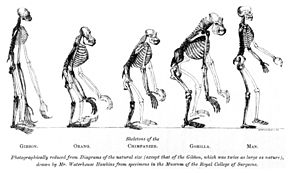

Thomas Henry Huxley's frontispiece to his 1863 book Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature was intended simply to compare the skeletons of apes and humans, but its unintentional left-to-right progressionist sequence has according to the historian Jennifer Tucker "become an iconic and instantly recognizable visual shorthand for evolution".[5]

An illustration, with the caption "Evolution", showing two sequences of four images, each illustrating a gradual transformation of an animal into a human, appeared in the 1889 edition[15] of Mark Twain's A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Shelley, Cameron (1 January 2001). "Aspects of visual argument: A study of the March of Progress". Informal Logic. 21 (2). University of Windsor Leddy Library. doi:10.22329/il.v21i2.2239. ISSN 0824-2577.

- ^ a b Lubbock, Tom (2008). "Art and evolution". The Lancet. 372: S14–S20. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61876-0. ISSN 0140-6736. S2CID 54266427.

- ^ a b Feteris, Eveline T.; Groarke, Leo; Plug, Jose (2011). "Strategic maneuvering with visual arguments in political cartoons: A pragma-dialectical analysis of the use of topoi that are based on common cultural heritage". In Feteris, Eveline T.; Garssen, Bart; Snoek Henkeamns, A. Francisca (eds.). Keeping in Touch With Pragma-Dialectics: in Honor of Frans H. Van Eemeren. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 67–69. ISBN 978-9027211811.

- ^ a b c d Howell, F. Clark and the Editors of Time-Life Books (1965), Early Man, New York: TIME-LIFE Books, pp. 41–45.

- ^ a b c Tucker, Jennifer (28 October 2012). "What our most famous evolutionary cartoon gets wrong". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ a b Barringer, David (2006) "Raining on Evolution’s Parade"; I.D. Magazine, March/April 2006.

- ^ a b c Gould, Stephen Jay (1989), Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. W.W. Norton & Company, pp 30–36.

- ^ Wells, Jonathan (2000). Icons of Evolution: Science or Myth?. Regnery Publishing. p. 211.

- ^ Black, Riley (3 December 2010). "Breaking our link to the 'March of Progress'". Scientific American. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ Black, Riley (11 April 2009). "The March of Progress has Deep Roots". Wired. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ Barringer (2006), Op. cit.

- ^ "The Story of Man". The Economist. 20 December 2005. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ^ Nast, C. (2022, April 28). Digga D: Noughty By Nature. Pitchfork. https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/digga-d-noughty-by-nature/

- ^ "Yume 2kki:Events". YumeWiki. 9 November 2024. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

- ^ Project Gutenberg text, search for second appearance of the word "crusher." Title page image shows "New York: Charles L. Webster & Company. 1889.

External links

[edit] Media related to March of Progress at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to March of Progress at Wikimedia Commons