Atlantis

Atlantis (Ancient Greek: Ἀτλαντὶς νῆσος, romanized: Atlantìs nêsos, lit. 'island of Atlas') is a fictional island mentioned in Plato's works Timaeus and Critias as part of an allegory on the hubris of nations. In the story, Atlantis is described as a naval empire that ruled all Western parts of the known world,[1][2] making it the literary counter-image of the Achaemenid Empire.[3] After an ill-fated attempt to conquer "Ancient Athens," Atlantis falls out of favor with the deities and submerges into the Atlantic Ocean. Since Plato describes Athens as resembling his ideal state in the Republic, the Atlantis story is meant to bear witness to the superiority of his concept of a state.[4][5]

Despite its minor importance in Plato's work, the Atlantis story has had a considerable impact on literature. The allegorical aspect of Atlantis was taken up in utopian works of several Renaissance writers, such as Francis Bacon's New Atlantis and Thomas More's Utopia.[6][7] On the other hand, nineteenth-century amateur scholars misinterpreted Plato's narrative as historical tradition, most famously Ignatius L. Donnelly in his Atlantis: The Antediluvian World. Plato's vague indications of the time of the events (more than 9,000 years before his time[8]) and the alleged location of Atlantis ("beyond the Pillars of Hercules") gave rise to much pseudoscientific speculation.[9] As a consequence, Atlantis has become a byword for any and all supposed advanced prehistoric lost civilizations and continues to inspire contemporary fiction, from comic books to films.

While present-day philologists and classicists agree on the story's fictional nature,[10][11] there is still debate on what served as its inspiration. Plato is known to have freely borrowed some of his allegories and metaphors from older traditions, as he did with the story of Gyges.[12] This led a number of scholars to suggest possible inspiration of Atlantis from Egyptian records of the Thera eruption,[13][14] the Sea Peoples invasion,[15] or the Trojan War.[16] Others have rejected this chain of tradition as implausible and insist that Plato created an entirely fictional account,[17][18][19] drawing loose inspiration from contemporary events such as the failed Athenian invasion of Sicily in 415–413 BC or the destruction of Helike in 373 BC.[20]

Plato's dialogues

Timaeus

The only primary sources for Atlantis are Plato's dialogues Timaeus and Critias; all other mentions of the island are based on them. The dialogues claim to quote Solon, who visited Egypt between 590 and 580 BC; they state that he translated Egyptian records of Atlantis.[21] Plato introduced Atlantis in Timaeus, written in 360 BC:

For it is related in our records how once upon a time your State stayed the course of a mighty host, which, starting from a distant point in the Atlantic ocean, was insolently advancing to attack the whole of Europe, and Asia to boot. For the ocean there was at that time navigable; for in front of the mouth which you Greeks call, as you say, 'the pillars of Heracles,' there lay an island which was larger than Libya and Asia together; and it was possible for the travelers of that time to cross from it to the other islands, and from the islands to the whole of the continent over against them which encompasses that veritable ocean. For all that we have here, lying within the mouth of which we speak, is evidently a haven having a narrow entrance; but that yonder is a real ocean, and the land surrounding it may most rightly be called, in the fullest and truest sense, a continent. Now in this island of Atlantis there existed a confederation of kings, of great and marvelous power, which held sway over all the island, and over many other islands also and parts of the continent.[22]

The four people appearing in those two dialogues are the politicians Critias and Hermocrates as well as the philosophers Socrates and Timaeus of Locri, although only Critias speaks of Atlantis. In his works Plato makes extensive use of the Socratic method in order to discuss contrary positions within the context of a supposition.

The Timaeus begins with an introduction, followed by an account of the creations and structure of the universe and ancient civilizations. In the introduction, Socrates muses about the perfect society, described in Plato's Republic (c. 380 BC), and wonders if he and his guests might recollect a story which exemplifies such a society. Critias mentions a tale he considered to be historical, that would make the perfect example, and he then follows by describing Atlantis as is recorded in the Critias. In his account, ancient Athens seems to represent the "perfect society" and Atlantis its opponent, representing the very antithesis of the "perfect" traits described in the Republic.

Critias

According to Critias, the Hellenic deities of old divided the land so that each deity might have their own lot; Poseidon was appropriately, and to his liking, bequeathed the island of Atlantis. The island was larger than Ancient Libya and Asia Minor combined,[23][24] but it was later sunk by an earthquake and became an impassable mud shoal, inhibiting travel to any part of the ocean. Plato asserted that the Egyptians described Atlantis as an island consisting mostly of mountains in the northern portions and along the shore and encompassing a great plain in an oblong shape in the south "extending in one direction three thousand stadia [about 555 km; 345 mi], but across the center inland it was two thousand stadia [about 370 km; 230 mi]." Fifty stadia [9 km; 6 mi] from the coast was a mountain that was low on all sides ... broke it off all round about ... the central island itself was five stades in diameter [about 0.92 km; 0.57 mi].

In Plato's metaphorical tale, Poseidon fell in love with Cleito, the daughter of Evenor and Leucippe, who bore him five pairs of male twins. The eldest of these, Atlas, was made rightful king of the entire island and the ocean (called the Atlantic Ocean in his honor), and was given the mountain of his birth and the surrounding area as his fiefdom. Atlas's twin Gadeirus, or Eumelus in Greek, was given the extremity of the island toward the pillars of Hercules.[25] The other four pairs of twins—Ampheres and Evaemon, Mneseus and Autochthon, Elasippus and Mestor, and Azaes and Diaprepes—were also given "rule over many men, and a large territory."

Poseidon carved the mountain where his love dwelt into a palace and enclosed it with three circular moats of increasing width, varying from one to three stadia and separated by rings of land proportional in size. The Atlanteans then built bridges northward from the mountain, making a route to the rest of the island. They dug a great canal to the sea, and alongside the bridges carved tunnels into the rings of rock so that ships could pass into the city around the mountain; they carved docks from the rock walls of the moats. Every passage to the city was guarded by gates and towers, and a wall surrounded each ring of the city. The walls were constructed of red, white, and black rock, quarried from the moats, and were covered with brass, tin, and the precious metal orichalcum, respectively.

According to Critias, 9,000 years before his lifetime a war took place between those outside the Pillars of Hercules at the Strait of Gibraltar and those who dwelt within them. The Atlanteans had conquered the parts of Libya within the Pillars of Hercules, as far as Egypt, and the European continent as far as Tyrrhenia, and had subjected its people to slavery. The Athenians led an alliance of resistors against the Atlantean empire, and as the alliance disintegrated, prevailed alone against the empire, liberating the occupied lands.

But afterwards there occurred violent earthquakes and floods; and in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea. For which reason the sea in those parts is impassable and impenetrable, because there is a shoal of mud in the way; and this was caused by the subsidence of the island.[26]

The logographer Hellanicus of Lesbos wrote an earlier work entitled Atlantis, of which only a few fragments survive. Hellanicus' work appears to have been a genealogical one concerning the daughters of Atlas (Ἀτλαντὶς in Greek means "of Atlas"),[13] but some authors have suggested a possible connection with Plato's island. John V. Luce notes that when Plato writes about the genealogy of Atlantis's kings, he writes in the same style as Hellanicus, suggesting a similarity between a fragment of Hellanicus's work and an account in the Critias.[13] Rodney Castleden suggests that Plato may have borrowed his title from Hellanicus, who may have based his work on an earlier work about Atlantis.[27]

Castleden has pointed out that Plato wrote of Atlantis in 359 BC, when he returned to Athens from Sicily. He notes a number of parallels between the physical organisation and fortifications of Syracuse and Plato's description of Atlantis.[28] Gunnar Rudberg was the first who elaborated upon the idea that Plato's attempt to realize his political ideas in the city of Syracuse could have heavily inspired the Atlantis account.[29]

Interpretations

Ancient

Some ancient writers viewed Atlantis as fictional or metaphorical myth; others believed it to be real.[30] Aristotle believed that Plato, his teacher, had invented the island to teach philosophy.[21] The philosopher Crantor, a student of Plato's student Xenocrates, is cited often as an example of a writer who thought the story to be historical fact. His work, a commentary on Timaeus, is lost, but Proclus, a Neoplatonist of the fifth century AD, reports on it.[31] The passage in question has been represented in the modern literature either as claiming that Crantor visited Egypt, had conversations with priests, and saw hieroglyphs confirming the story, or, as claiming that he learned about them from other visitors to Egypt.[32] Proclus wrote:

As for the whole of this account of the Atlanteans, some say that it is unadorned history, such as Crantor, the first commentator on Plato. Crantor also says that Plato's contemporaries used to criticize him jokingly for not being the inventor of his Republic but copying the institutions of the Egyptians. Plato took these critics seriously enough to assign to the Egyptians this story about the Athenians and Atlanteans, so as to make them say that the Athenians really once lived according to that system.

The next sentence is often translated "Crantor adds, that this is testified by the prophets of the Egyptians, who assert that these particulars [which are narrated by Plato] are written on pillars which are still preserved." But in the original, the sentence starts not with the name Crantor but with the ambiguous He; whether this referred to Crantor or to Plato is the subject of considerable debate. Proponents of both Atlantis as a metaphorical myth and Atlantis as history have argued that the pronoun refers to Crantor.[33]

Alan Cameron argues that the pronoun should be interpreted as referring to Plato, and that, when Proclus writes that "we must bear in mind concerning this whole feat of the Athenians, that it is neither a mere myth nor unadorned history, although some take it as history and others as myth", he is treating "Crantor's view as mere personal opinion, nothing more; in fact he first quotes and then dismisses it as representing one of the two unacceptable extremes".[34]

Cameron also points out that whether he refers to Plato or to Crantor, the statement does not support conclusions such as Otto Muck's "Crantor came to Sais and saw there in the temple of Neith the column, completely covered with hieroglyphs, on which the history of Atlantis was recorded. Scholars translated it for him, and he testified that their account fully agreed with Plato's account of Atlantis"[35] or J. V. Luce's suggestion that Crantor sent "a special enquiry to Egypt" and that he may simply be referring to Plato's own claims.[34]

Another passage from the commentary by Proclus on the Timaeus gives a description of the geography of Atlantis:

That an island of such nature and size once existed is evident from what is said by certain authors who investigated the things around the outer sea. For according to them, there were seven islands in that sea in their time, sacred to Persephone, and also three others of enormous size, one of which was sacred to Hades, another to Ammon, and another one between them to Poseidon, the extent of which was a thousand stadia [200 km; 124 mi]; and the inhabitants of it—they add—preserved the remembrance from their ancestors of the immeasurably large island of Atlantis which had really existed there and which for many ages had reigned over all islands in the Atlantic sea and which itself had like-wise been sacred to Poseidon. Now these things Marcellus has written in his Aethiopica.[36]

Marcellus remains unidentified.

Other ancient historians and philosophers who believed in the existence of Atlantis were Strabo and Posidonius.[37] Some have theorized that, before the sixth century BC, the "Pillars of Hercules" may have applied to mountains on either side of the Gulf of Laconia, and also may have been part of the pillar cult of the Aegean.[38][39] The mountains stood at either side of the southernmost gulf in Greece, the largest in the Peloponnese, and it opens onto the Mediterranean Sea. This would have placed Atlantis in the Mediterranean, lending credence to many details in Plato's discussion.

The fourth-century historian Ammianus Marcellinus, relying on a lost work by Timagenes, a historian writing in the first century BC, writes that the Druids of Gaul said that part of the inhabitants of Gaul had migrated there from distant islands. Some have understood Ammianus's testimony as a claim that at the time of Atlantis's sinking into the sea, its inhabitants fled to western Europe; but Ammianus, in fact, says that "the Drasidae (Druids) recall that a part of the population is indigenous but others also migrated in from islands and lands beyond the Rhine" (Res Gestae 15.9), an indication that the immigrants came to Gaul from the north (Britain, the Netherlands, or Germany), not from a theorized location in the Atlantic Ocean to the south-west.[40] Instead, the Celts who dwelled along the ocean were reported to venerate twin gods, (Dioscori), who appeared to them coming from that ocean.[41]

Jewish and Christian

During the early first century, the Hellenistic Jewish philosopher Philo wrote about the destruction of Atlantis in his On the Eternity of the World, xxvi. 141, in a longer passage allegedly citing Aristotle's successor Theophrastus:[42]

... And the island of Atalantes [translator's spelling; original: "Ἀτλαντίς"] which was greater than Africa and Asia, as Plato says in the Timaeus, in one day and night was overwhelmed beneath the sea in consequence of an extraordinary earthquake and inundation and suddenly disappeared, becoming sea, not indeed navigable, but full of gulfs and eddies.[43]

The theologian Joseph Barber Lightfoot (Apostolic Fathers, 1885, II, p. 84) noted on this passage: "Clement may possibly be referring to some known, but hardly accessible land, lying without the pillars of Hercules. But more probably he contemplated some unknown land in the far west beyond the ocean, like the fabled Atlantis of Plato ..."[44]

Other early Christian writers wrote about Atlantis, although they had mixed views on whether it once existed or was an untrustworthy myth of pagan origin.[45] Tertullian believed Atlantis was once real and wrote that in the Atlantic Ocean once existed "[the isle] that was equal in size to Libya or Asia"[46] referring to Plato's geographical description of Atlantis. The early Christian apologist writer Arnobius also believed Atlantis once existed, but blamed its destruction on pagans.[47]

Cosmas Indicopleustes in the sixth century wrote of Atlantis in his Christian Topography in an attempt to prove his theory that the world was flat and surrounded by water:[48][page needed]

... In like manner the philosopher Timaeus also describes this Earth as surrounded by the Ocean, and the Ocean as surrounded by the more remote earth. For he supposes that there is to westward an island, Atlantis, lying out in the Ocean, in the direction of Gadeira (Cadiz), of an enormous magnitude, and relates that the ten kings having procured mercenaries from the nations in this island came from the earth far away, and conquered Europe and Asia, but were afterwards conquered by the Athenians, while that island itself was submerged by God under the sea. Both Plato and Aristotle praise this philosopher, and Proclus has written a commentary on him. He himself expresses views similar to our own with some modifications, transferring the scene of the events from the east to the west. Moreover he mentions those ten generations as well as that earth which lies beyond the Ocean. And in a word it is evident that all of them borrow from Moses, and publish his statements as their own.[49]

Modern

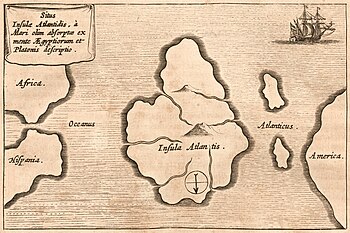

Aside from Plato's original account, modern interpretations regarding Atlantis are an amalgamation of diverse, speculative movements that began in the sixteenth century,[51] when scholars began to identify Atlantis with the New World. Francisco Lopez de Gomara was the first to state that Plato was referring to America, as did Francis Bacon and Alexander von Humboldt; Janus Joannes Bircherod said in 1663 orbe novo non-novo ("the New World is not new"). Athanasius Kircher accepted Plato's account as literally true, describing Atlantis as a small continent in the Atlantic Ocean.[21]

Contemporary perceptions of Atlantis share roots with Mayanism, which can be traced to the beginning of the Modern Age, when European imaginations were fueled by their initial encounters with the indigenous peoples of the Americas.[52] From this era sprang apocalyptic and utopian visions that would inspire many subsequent generations of theorists.[52]

Most of these interpretations are considered pseudohistory, pseudoscience, or pseudoarchaeology, as they have presented their works as academic or scientific, but lack the standards or criteria.

The Flemish cartographer and geographer Abraham Ortelius is believed to have been the first person to imagine that the continents were joined before drifting to their present positions. In the 1596 edition of his Thesaurus Geographicus he wrote: "Unless it be a fable, the island of Gadir or Gades [Cadiz] will be the remaining part of the island of Atlantis or America, which was not sunk (as Plato reports in the Timaeus) so much as torn away from Europe and Africa by earthquakes and flood... The traces of the ruptures are shown by the projections of Europe and Africa and the indentations of America in the parts of the coasts of these three said lands that face each other to anyone who, using a map of the world, carefully considered them. So that anyone may say with Strabo in Book 2, that what Plato says of the island of Atlantis on the authority of Solon is not a figment."[53]

Early influential literature

The term "utopia" (from "no place") was coined by Sir Thomas More in his sixteenth-century work of fiction Utopia.[54] Inspired by Plato's Atlantis and travelers' accounts of the Americas, More described an imaginary land set in the New World.[55] His idealistic vision established a connection between the Americas and utopian societies, a theme that Bacon discussed in The New Atlantis (c. 1623).[52] A character in the narrative gives a history of Atlantis that is similar to Plato's and places Atlantis in America. People had begun believing that the Mayan and Aztec ruins could possibly be the remnants of Atlantis.[54]

Impact of Mayanism

Much speculation began as to the origins of the Maya, which led to a variety of narratives and publications that tried to rationalize the discoveries within the context of the Bible and that had undertones of racism in their connections between the Old and New World. The Europeans believed the indigenous people to be inferior and incapable of building that which was now in ruins and by sharing a common history, they insinuated that another race must have been responsible.

In the middle and late nineteenth century, several renowned Mesoamerican scholars, starting with Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg, and including Edward Herbert Thompson and Augustus Le Plongeon, formally proposed that Atlantis was somehow related to Mayan and Aztec culture.

The French scholar Brasseur de Bourbourg traveled extensively through Mesoamerica in the mid-1800s, and was renowned for his translations of Mayan texts, most notably the sacred book Popol Vuh, as well as a comprehensive history of the region. Soon after these publications, however, Brasseur de Bourbourg lost his academic credibility, due to his claim that the Maya peoples had descended from the Toltecs, people he believed were the surviving population of the racially superior civilization of Atlantis.[56] His work combined with the skillful, romantic illustrations of Jean Frederic Waldeck, which visually alluded to Egypt and other aspects of the Old World, created an authoritative fantasy that excited much interest in the connections between worlds.

Inspired by Brasseur de Bourbourg's diffusion theories, the pseudoarchaeologist Augustus Le Plongeon traveled to Mesoamerica and performed some of the first excavations of many famous Mayan ruins. Le Plongeon invented narratives, such as the kingdom of Mu saga, which romantically drew connections to him, his wife Alice, and Egyptian deities Osiris and Isis, as well as to Heinrich Schliemann, who had just discovered the ancient city of Troy from Homer's epic poetry (that had been described as merely mythical).[57][page range too broad] He also believed that he had found connections between the Greek and Mayan languages, which produced a narrative of the destruction of Atlantis.[58]

Ignatius Donnelly

The 1882 publication of Atlantis: the Antediluvian World by Ignatius L. Donnelly stimulated much popular interest in Atlantis. He was greatly inspired by early works in Mayanism, and like them, attempted to establish that all known ancient civilizations were descended from Atlantis, which he saw as a technologically sophisticated, more advanced culture. Donnelly drew parallels between creation stories in the Old and New Worlds, attributing the connections to Atlantis, where he believed the Biblical Garden of Eden existed.[59] As implied by the title of his book, he also believed that Atlantis was destroyed by the Great Flood mentioned in the Bible.

Donnelly is credited as the "father of the nineteenth century Atlantis revival" and is the reason the myth endures today.[60] He unintentionally promoted an alternative method of inquiry to history and science, and the idea that myths contain hidden information that opens them to "ingenious" interpretation by people who believe they have new or special insight.[61]

Madame Blavatsky and the Theosophists

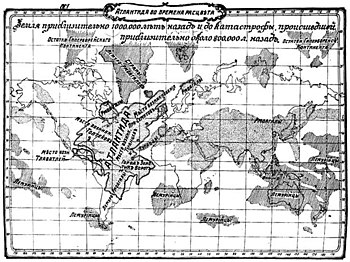

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, the founder of the Theosophists, took up Donnelly's interpretations when she wrote The Secret Doctrine (1888), which she claimed was originally dictated in Atlantis. She maintained that the Atlanteans were cultural heroes (contrary to Plato, who describes them mainly as a military threat). She believed in a form of racial evolution (as opposed to primate evolution). In her process of evolution the Atlanteans were the fourth "root race", which were succeeded by the fifth, the "Aryan race", which she identified with the modern human race.[54]

In her book, Blavatsky reported that the civilization of Atlantis reached its peak between 1,000,000 and 900,000 years ago, but destroyed itself through internal warfare brought about by the dangerous use of psychic and supernatural powers of the inhabitants. Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy and Waldorf Schools, along with other well known Theosophists, such as Annie Besant, also wrote of cultural evolution in much the same vein. Other occultists followed the same lead, at least to the point of tracing the lineage of occult practices back to Atlantis. Among the most famous is Dion Fortune in her Esoteric Orders and Their Work.[62]

Drawing on the ideas of Rudolf Steiner and Hanns Hörbiger, Egon Friedell started his book Kulturgeschichte des Altertums, and thus his historical analysis of antiquity, with the ancient culture of Atlantis. The book was published in 1940.

Nazism and occultism

Blavatsky was also inspired by the work of the 18th-century astronomer Jean-Sylvain Bailly, who had "Orientalized" the Atlantis myth in his mythical continent of Hyperborea, a reference to Greek myths featuring a Northern European region of the same name, home to a giant, godlike race.[63][64] Dan Edelstein claims that her reshaping of this theory in The Secret Doctrine provided the Nazis with a mythological precedent and a pretext for their ideological platform and their subsequent genocide.[63] However, Blavatsky's writings mention that the Atlantean were in fact olive-skinned peoples with Mongoloid traits who were the ancestors of modern Native Americans, Mongolians, and Malayans.[65][66][67]

The idea that the Atlanteans were Hyperborean, Nordic supermen who originated in the Northern Atlantic or even in the far North, was popular in the German ariosophic movement around 1900, propagated by Guido von List and others.[68] It gave its name to the Thule Gesellschaft, an antisemite Münich lodge, which preceded the German Nazi Party (see Thule). The scholars Karl Georg Zschaetzsch (1920) and Herman Wirth (1928) were the first to speak of a "Nordic-Atlantean" or "Aryan-Nordic" master race that spread from Atlantis over the Northern Hemisphere and beyond. The Hyperboreans were contrasted with the Jewish people. Party ideologist Alfred Rosenberg (in The Myth of the Twentieth Century, 1930) and SS-leader Heinrich Himmler made it part of the official doctrine.[69] The idea was followed up by the adherents of Esoteric Nazism such as Julius Evola (1934) and, more recently, Miguel Serrano (1978).

The idea of Atlantis as the homeland of the Caucasian race would contradict the beliefs of older Esoteric and Theosophic groups, which taught that the Atlanteans were non-Caucasian brown-skinned peoples. Modern Esoteric groups, including the Theosophic Society, do not consider Atlantean society to have been superior or Utopian—they rather consider it a lower stage of evolution.[70]

Edgar Cayce

The clairvoyant Edgar Cayce spoke frequently of Atlantis. During his "life readings", he claimed that many of his subjects were reincarnations of people who had lived there. By tapping into their collective consciousness, the "Akashic Records" (a term borrowed from Theosophy),[71] Cayce declared that he was able to give detailed descriptions of the lost continent.[72] He also asserted that Atlantis would "rise" again in the 1960s (sparking much popularity of the myth in that decade) and that there is a "Hall of Records" beneath the Egyptian Sphinx which holds the historical texts of Atlantis.

Recent times

As continental drift became widely accepted during the 1960s, and the increased understanding of plate tectonics demonstrated the impossibility of a lost continent in the geologically recent past,[73] most "Lost Continent" theories of Atlantis began to wane in popularity.

Plato scholar Julia Annas, Regents Professor of Philosophy at the University of Arizona, had this to say on the matter:

The continuing industry of discovering Atlantis illustrates the dangers of reading Plato. For he is clearly using what has become a standard device of fiction—stressing the historicity of an event (and the discovery of hitherto unknown authorities) as an indication that what follows is fiction. The idea is that we should use the story to examine our ideas of government and power. We have missed the point if instead of thinking about these issues we go off exploring the sea bed. The continuing misunderstanding of Plato as historian here enables us to see why his distrust of imaginative writing is sometimes justified.[74]

One of the proposed explanations for the historical context of the Atlantis story is that it serves as Plato's warning to his fellow citizens against their striving for naval power.[19]

Kenneth Feder points out that Critias's story in the Timaeus provides a major clue. In the dialogue, Critias says, referring to Socrates' hypothetical society:

And when you were speaking yesterday about your city and citizens, the tale which I have just been repeating to you came into my mind, and I remarked with astonishment how, by some mysterious coincidence, you agreed in almost every particular with the narrative of Solon. ...[75]

Feder quotes A. E. Taylor, who wrote, "We could not be told much more plainly that the whole narrative of Solon's conversation with the priests and his intention of writing the poem about Atlantis are an invention of Plato's fancy."[76]

Location hypotheses

Since Donnelly's day, there have been dozens of locations proposed for Atlantis, to the point where the name has become a generic concept, divorced from the specifics of Plato's account. This is reflected in the fact that many proposed sites are not within the Atlantic at all. Few today are scholarly or archaeological hypotheses, while others have been made by psychic (e.g., Edgar Cayce) or other pseudoscientific means. (The Atlantis researchers Jacques Collina-Girard and Georgeos Díaz-Montexano, for instance, each claim the other's hypothesis is pseudoscience.)[77] Many of the proposed sites share some of the characteristics of the Atlantis story (water, catastrophic end, relevant time period), but none has been demonstrated to be a true historical Atlantis.

In or near the Mediterranean Sea

Most of the historically proposed locations are in or near the Mediterranean Sea: islands such as Sardinia,[78][79][80] Crete, Santorini (Thera), Sicily, Cyprus, and Malta; land-based cities or states such as Troy,[81][page needed] Tartessos, and Tantalis (in the province of Manisa, Turkey);[82] Israel-Sinai or Canaan;[citation needed] and northwestern Africa,[83] including the Richat Structure in Mauritania.[84]

The Thera eruption, dated to the seventeenth or sixteenth century BC, caused a large tsunami that some experts hypothesize devastated the Minoan civilization on the nearby island of Crete, further leading some to believe that this may have been the catastrophe that inspired the story.[85][86] In the area of the Black Sea the following locations have been proposed: Bosporus and Ancomah (a legendary place near Trabzon).

Others have noted that, before the sixth century BC, the mountains on either side of the Laconian Gulf were called the "Pillars of Hercules",[38][39] and they could be the geographical location being described in ancient reports upon which Plato was basing his story. The mountains stood at either side of the southernmost gulf in Greece, the largest in the Peloponnese, and that gulf opens onto the Mediterranean Sea.

If from the beginning of discussions, misinterpretation of Gibraltar as the location rather than being at the Gulf of Laconia, would lend itself to many erroneous concepts regarding the location of Atlantis. Plato may have not been aware of the difference. The Laconian pillars open to the south toward Crete and beyond which is Egypt. The Thera eruption and the Late Bronze Age collapse affected that area and might have been the devastation to which the sources used by Plato referred. Significant events such as these would have been likely material for tales passed from one generation to another for almost a thousand years.

In the Atlantic Ocean

The location of Atlantis in the Atlantic Ocean has a certain appeal given the closely related names. Popular culture often places Atlantis there, perpetuating the original Platonic setting as they understand it. The Canary Islands and Madeira Islands have been identified as a possible location,[87][88][89][90] west of the Straits of Gibraltar, but in relative proximity to the Mediterranean Sea. Detailed studies of their geomorphology and geology have demonstrated, however, that they have been steadily uplifted, without any significant periods of subsidence, over the last four million years, by geologic processes such as erosional unloading, gravitational unloading, lithospheric flexure induced by adjacent islands, and volcanic underplating.[91][92]

Various islands or island groups in the Atlantic were also identified as possible locations, notably the Azores.[89][90] Similarly, cores of sediment covering the ocean bottom surrounding the Azores and other evidence demonstrate that it has been an undersea plateau for millions of years.[93][94] The area is known for its volcanism however, which is associated with rifting along the Azores triple junction. The spread of the crust along the existing faults and fractures has produced many volcanic and seismic events.[95]

The area is supported by a buoyant upwelling in the deeper mantle, which some associate with an Azores hotspot.[96] Most of the volcanic activity has occurred primarily along the Terceira Rift. From the beginning of the islands' settlement, around the 15th century, there have been about 30 volcanic eruptions (terrestrial and submarine) as well as numerous, powerful earthquakes.[97] The island of São Miguel in the Azores is the site of the Sete Cidades volcano and caldera, which are the byproducts of historical volcanic activity in the Azores.[98]

The submerged island of Spartel near the Strait of Gibraltar has also been suggested.[99]

In Europe

Several hypotheses place the sunken island in northern Europe, including Doggerland in the North Sea, and Sweden (by Olof Rudbeck in Atland, 1672–1702). Doggerland, as well as Viking Bergen Island, is thought to have been flooded by a megatsunami following the Storegga Slide of c. 6100 BC. Some have proposed the Celtic Shelf as a possible location, and that there is a link to Ireland.[100] In 2004, Swedish physiographist Ulf Erlingsson[101] proposed that the legend of Atlantis was based on Stone Age Ireland. He later stated that he does not believe that Atlantis ever existed but maintained that his hypothesis that its description matches Ireland's geography has a 99.8% probability. The director of the National Museum of Ireland commented that there was no archaeology supporting this.[102]

In 2011, a team, working on a documentary for the National Geographic Channel,[103] led by Professor Richard Freund from the University of Hartford, claimed to have found possible evidence of Atlantis in southwestern Andalusia.[104] The team identified its possible location within the marshlands of the Doñana National Park, in the area that once was the Lacus Ligustinus,[105] between the Huelva, Cádiz, and Seville provinces, and they speculated that Atlantis had been destroyed by a tsunami,[106] extrapolating results from a previous study by Spanish researchers, published four years earlier.[107]

Spanish scientists have dismissed Freund's speculations, claiming that he sensationalised their work. The anthropologist Juan Villarías-Robles, who works with the Spanish National Research Council, said, "Richard Freund was a newcomer to our project and appeared to be involved in his own very controversial issue concerning King Solomon's search for ivory and gold in Tartessos, the well documented settlement in the Doñana area established in the first millennium BC", and described Freund's claims as "fanciful".[108]

A similar theory had previously been put forward by a German researcher, Rainer W. Kühne, that is based only on satellite imagery and places Atlantis in the Marismas de Hinojos, north of the city of Cádiz.[99] Before that, the historian Adolf Schulten had stated in the 1920s that Plato had used Tartessos as the basis for his Atlantis myth.[109]

Other locations

Several writers, such as Flavio Barbiero as early as 1974,[110] have speculated that Antarctica is the site of Atlantis.[111][112][page needed] A number of claims involve the Caribbean, such as an alleged underwater formation off the Guanahacabibes Peninsula in Cuba.[113] The adjacent Bahamas or the folkloric Bermuda Triangle have been proposed as well. Areas in the Pacific and Indian Oceans have also been proposed, including Indonesia (i.e. Sundaland).[114][page needed] The stories of a lost continent off the coast of India, named "Kumari Kandam", have inspired some to draw parallels to Atlantis.[115][page needed]

Literary interpretations

Ancient versions

In order to give his account of Atlantis verisimilitude, Plato mentions that the story was heard by Solon in Egypt, and transmitted orally over several generations through the family of Dropides, until it reached Critias, a dialogue speaker in Timaeus and Critias.[116] Solon had supposedly tried to adapt the Atlantis oral tradition into a poem (that if published, was to be greater than the works of Hesiod and Homer). While it was never completed, Solon passed on the story to Dropides. Modern classicists deny the existence of Solon's Atlantis poem and the story as an oral tradition.[117]

Instead, Plato is thought to be the sole inventor or fabricator. Hellanicus of Lesbos used the word "Atlantis" as the title for a poem published before Plato,[118] a fragment of which may be Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 11, 1359.[119] This work only describes the Atlantides, the daughters of Atlas, and has no relation to Plato's Atlantis account.

In the new era, the third century AD Neoplatonist Zoticus wrote an epic poem based on Plato's account of Atlantis.[120] Plato's work may already have inspired parodic imitation, however. Writing only a few decades after the Timaeus and Critias, the historian Theopompus of Chios wrote of a land beyond the ocean known as Meropis. This description was included in Book 8 of his Philippica, which contains a dialogue between Silenus and King Midas. Silenus describes the Meropids, a race of men who grow to twice normal size, and inhabit two cities on the island of Meropis: Eusebes (Εὐσεβής, "Pious-town") and Machimos (Μάχιμος, "Fighting-town").[121]

He also reports that an army of ten million soldiers crossed the ocean to conquer Hyperborea, but abandoned this proposal when they realized that the Hyperboreans were the luckiest people on earth. Heinz-Günther Nesselrath has argued that these and other details of Silenus' story are meant as imitation and exaggeration of the Atlantis story, by parody, for the purpose of exposing Plato's ideas to ridicule.[122]

Utopias and dystopias

The creation of Utopian and dystopian fictions was renewed after the Renaissance, most notably in Francis Bacon's New Atlantis (1627), the description of an ideal society that he located off the western coast of America. Thomas Heyrick (1649–1694) followed him with "The New Atlantis" (1687), a satirical poem in three parts. His new continent of uncertain location, perhaps even a floating island either in the sea or the sky, serves as background for his exposure of what he described in a second edition as "A True Character of Popery and Jesuitism".[123]

The title of The New Atalantis by Delarivier Manley (1709), distinguished from the two others by the single letter, is an equally dystopian work but set this time on a fictional Mediterranean island.[124] In it sexual violence and exploitation is made a metaphor for the hypocritical behaviour of politicians in their dealings with the general public.[125] In Manley's case, the target of satire was the Whig Party, while in David Maclean Parry's The Scarlet Empire (1906) it is Socialism as practised in foundered Atlantis.[126] It was followed in Russia by Velimir Khlebnikov's poem The Fall of Atlantis (Gibel' Atlantidy, 1912), which is set in a future rationalist dystopia that has discovered the secret of immortality and is so dedicated to progress that it has lost touch with the past. When the high priest of this ideology is tempted by a slave girl into an act of irrationality, he murders her and precipitates a second flood, above which her severed head floats vengefully among the stars.[127]

A slightly later work, The Ancient of Atlantis (Boston, 1915) by Albert Armstrong Manship, expounds the Atlantean wisdom that is to redeem the earth. Its three parts consist of a verse narrative of the life and training of an Atlantean wise one, followed by his Utopian moral teachings and then a psychic drama set in modern times in which a reincarnated child embodying the lost wisdom is reborn on earth.[128]

In Hispanic eyes, Atlantis had a more intimate interpretation. The land had been a colonial power which, although it had brought civilization to ancient Europe, had also enslaved its peoples. Its tyrannical fall from grace had contributed to the fate that had overtaken it, but now its disappearance had unbalanced the world. This was the point of view of Jacint Verdaguer's vast mythological epic L'Atlantida (1877). After the sinking of the former continent, Hercules travels east across the Atlantic to found the city of Barcelona and then departs westward again to the Hesperides. The story is told by a hermit to a shipwrecked mariner, who is inspired to follow in his tracks and so "call the New World into existence to redress the balance of the Old". This mariner, of course, was Christopher Columbus.[129]

Verdaguer's poem was written in Catalan, but was widely translated in both Europe and Hispano-America.[130] One response was the similarly entitled Argentinian Atlantida of Olegario Víctor Andrade (1881), which sees in "Enchanted Atlantis that Plato foresaw, a golden promise to the fruitful race" of Latins.[131] The bad example of the colonising world remains, however. José Juan Tablada characterises its threat in his "De Atlántida" (1894) through the beguiling picture of the lost world populated by the underwater creatures of Classical myth, among whom is the Siren of its final stanza with

her eye on the keel of the wandering vessel

that in passing deflowers the sea's smooth mirror,

launching into the night her amorous warbling

and the dulcet lullaby of her treacherous voice![132]

There is a similar ambivalence in Janus Djurhuus' six-stanza "Atlantis" (1917), where a celebration of the Faroese linguistic revival grants it an ancient pedigree by linking Greek to Norse legend. In the poem a female figure rising from the sea against a background of Classical palaces is recognised as a priestess of Atlantis. The poet recalls "that the Faroes lie there in the north Atlantic Ocean/ where before lay the poet-dreamt lands," but also that in Norse belief, such a figure only appears to those about to drown.[133]

A land lost in the distance

The fact that Atlantis is a lost land has made of it a metaphor for something no longer attainable. For the American poet Edith Willis Linn Forbes, "The Lost Atlantis" stands for idealisation of the past; the present moment can only be treasured once that is realised.[134] Ella Wheeler Wilcox finds the location of "The Lost Land" (1910) in one's carefree youthful past.[135] Similarly, for the Irish poet Eavan Boland in "Atlantis, a lost sonnet" (2007), the idea was defined when "the old fable-makers searched hard for a word/ to convey that what is gone is gone forever".[136]

For some male poets too, the idea of Atlantis is constructed from what cannot be obtained. Charles Bewley in his Newdigate Prize poem (1910) thinks it grows from dissatisfaction with one's condition,

And, because life is partly sweet

And ever girt about with pain,

We take the sweetness, and are fain

To set it free from grief's alloy

in a dream of Atlantis.[137] Similarly for the Australian Gary Catalano in a 1982 prose poem, it is "a vision that sank under the weight of its own perfection".[138] W. H. Auden, however, suggests a way out of such frustration through the metaphor of journeying toward Atlantis in his poem of 1941.[139] While travelling, he advises the one setting out, you will meet with many definitions of the goal in view, only realising at the end that the way has all the time led inward.[140]

Epic verse narratives

A few late-19th century verse narratives complement the genre fiction that was beginning to be written at the same period. Two of them report the disaster that overtook the continent as related by long-lived survivors. In Frederick Tennyson's Atlantis (1888), an ancient Greek mariner sails west and discovers an inhabited island which is all that remains of the former kingdom. He learns of its end and views the shattered remnant of its former glory, from which a few had escaped to set up the Mediterranean civilisations.[141] In the second, Mona, Queen of Lost Atlantis: An Idyllic Re-embodiment of Long Forgotten History (Los Angeles CA 1925) by James Logue Dryden (1840–1925), the story is told in a series of visions. A Seer is taken to Mona's burial chamber in the ruins of Atlantis, where she revives and describes the catastrophe. There follows a survey of the lost civilisations of Hyperborea and Lemuria as well as Atlantis, accompanied by much spiritualist lore.[142]

William Walton Hoskins (1856–1919) admits to the readers of his Atlantis and other poems (Cleveland OH, 1881), that he is only 24. Its melodramatic plot concerns the poisoning of the descendant of god-born kings. The usurping poisoner is poisoned in his turn, following which the continent is swallowed in the waves.[143] Asian gods people the landscape of The Lost Island (Ottawa 1889) by Edward Taylor Fletcher (1816–97). An angel foresees impending catastrophe and that the people will be allowed to escape if their semi-divine rulers will sacrifice themselves.[144] A final example, Edward N. Beecher's The Lost Atlantis or The Great Deluge of All (Cleveland OH, 1898) is just a doggerel vehicle for its author's opinions: that the continent was the location of the Garden of Eden; that Darwin's theory of evolution is correct, as are Donnelly's views.[145]

Atlantis was to become a theme in Russia following the 1890s, taken up in unfinished poems by Valery Bryusov and Konstantin Balmont, as well as in a drama by the schoolgirl Larissa Reisner.[146] One other long narrative poem was published in New York by George V. Golokhvastoff. His 250-page The Fall of Atlantis (1938) records how a high priest, distressed by the prevailing degeneracy of the ruling classes, seeks to create an androgynous being from royal twins as a means to overcome this polarity. When he is unable to control the forces unleashed by his occult ceremony, the continent is destroyed.[147]

Artistic representations

Music

The Spanish composer Manuel de Falla worked on a dramatic cantata based on Verdaguer's L'Atlántida, during the last 20 years of his life.[148] The name has been affixed to symphonies by Jānis Ivanovs (Symphony 4, 1941),[149] Richard Nanes,[150] and Vaclav Buzek (2009).[151] There was also the symphonic celebration of Alan Hovhaness: "Fanfare for the New Atlantis" (Op. 281, 1975).[152]

The Bohemian-American composer and arranger Vincent Frank Safranek wrote Atlantis (The Lost Continent) Suite in Four Parts; I. Nocturne and Morning Hymn of Praise, II. A Court Function, III. "I Love Thee" (The Prince and Aana), IV. The Destruction of Atlantis, for military (concert) band in 1913.[153]

The opera Der Kaiser von Atlantis (The Emperor of Atlantis) was written in 1943 by Viktor Ullmann with a libretto by Petr Kien, while they were both inmates at the Nazi concentration camp of Theresienstadt. The Nazis did not allow it to be performed, assuming the opera's reference to an Emperor of Atlantis to be a satire on Hitler. Though Ullmann and Kiel were murdered in Auschwitz, the manuscript survived and was performed for the first time in 1975 in Amsterdam.[154][155][156]

Painting and sculpture

Paintings of the submersion of Atlantis are comparatively rare. In the seventeenth century there was François de Nomé's The Fall of Atlantis, which shows a tidal wave surging toward a Baroque city frontage. The style of architecture apart, it is not very different from Nicholas Roerich's The Last of Atlantis of 1928.

The most dramatic depiction of the catastrophe was Léon Bakst's Ancient Terror (Terror Antiquus, 1908), although it does not name Atlantis directly. It is a mountain-top view of a rocky bay breached by the sea, which is washing inland about the tall structures of an ancient city. A streak of lightning crosses the upper half of the painting, while below it rises the impassive figure of an enigmatic goddess who holds a blue dove between her breasts. Vyacheslav Ivanov identified the subject as Atlantis in a public lecture on the painting given in 1909, the year it was first exhibited, and he has been followed by other commentators in the years since.[157]

Sculptures referencing Atlantis have often been stylized single figures. One of the earliest was Einar Jónsson's The King of Atlantis (1919–1922), now in the garden of his museum in Reykjavík. It represents a single figure, clad in a belted skirt and wearing a large triangular helmet, who sits on an ornate throne supported between two young bulls.[158] The walking female entitled Atlantis (1946) by Ivan Meštrović[159] was from a series inspired by ancient Greek figures[160] with the symbolical meaning of unjustified suffering.[161]

In the case of the Brussels fountain feature known as The Man of Atlantis (2003) by the Belgian sculptor Luk van Soom, the 4-metre tall figure wearing a diving suit steps from a plinth into the spray.[162] It looks light-hearted but the artist's comment on it makes a serious point: "Because habitable land will be scarce, it is no longer improbable that we will return to the water in the long term. As a result, a portion of the population will mutate into fish-like creatures. Global warming and rising water levels are practical problems for the world in general and here in the Netherlands in particular".[163]

Robert Smithson's Hypothetical Continent – Map of Broken Clear Glass: Atlantis was first created as a photographical project in Loveladies, New Jersey, in 1969,[164] and then recreated as a gallery installation of broken glass.[165] On this he commented that he liked "landscapes that suggest prehistory", and this is borne out by the original conceptual drawing of the work that includes an inset map of the continent sited off the coast of Africa and at the straits into the Mediterranean.[166]

See also

Mythology:

Underwater geography:

Other:

Notes

- ^ Plato's contemporaries pictured the world as consisting of only Europe, Northern Africa, and Western Asia (see the map of Hecataeus of Miletus).

- ^ Hale, John R. (2009). Lords of the Sea: The Epic Story of the Athenian Navy and the Birth of Democracy. New York: Penguin. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-670-02080-5.

Plato also wrote the myth of Atlantis as an allegory of the archetypal thalassocracy or naval power.

- ^ Welliver, Warman (1977). Character, Plot and Thought in Plato's Timaeus-Critias. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 42. ISBN 978-90-04-04870-6.

- ^ Hackforth, R. (1944). "The Story of Atlantis: Its Purpose and Its Moral". Classical Review. 58 (1): 7–9. doi:10.1017/s0009840x00089356. ISSN 0009-840X. JSTOR 701961. S2CID 162292186.

- ^ David, Ephraim (1984). "The Problem of Representing Plato's Ideal State in Action". Riv. Fil. 112: 33–53.

- ^ Mumford, Lewis (1965). "Utopia, the City and the Machine". Daedalus. 94 (2): 271–292. JSTOR 20026910.

- ^ Hartmann, Anna-Maria (2015). "The Strange Antiquity of Francis Bacon's New Atlantis". Renaissance Studies. 29 (3): 375–393. doi:10.1111/rest.12084. S2CID 161272260.

- ^ The frame story in Critias tells about an alleged visit of the Athenian lawmaker Solon (c. 638 BC – 558 BC) to Egypt, where he was told the Atlantis story that supposedly occurred 9,000 years before his time.

- ^ Feder, Kenneth (2011). "Lost: One Continent - Reward". Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology (Seventh ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 141–164. ISBN 978-0-07-811697-1.

- ^ Clay, Diskin (2000). "The Invention of Atlantis: The Anatomy of a Fiction". In Cleary, John J.; Gurtler, Gary M. (eds.). Proceedings of the Boston Area Colloquium in Ancient Philosophy. Vol. 15. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-90-04-11704-4.

- ^ "As Smith discusses in the opening article in this theme issue, the lost island-continent was – in all likelihood – entirely Plato's invention for the purposes of illustrating arguments around Grecian polity. Archaeologists broadly agree with the view that Atlantis is quite simply 'utopia' (Doumas, 2007), a stance also taken by classical philologists, who interpret Atlantis as a metaphorical rather than an actual place (Broadie, 2013; Gill, 1979; Nesselrath, 2002). One might consider the question as being already reasonably solved but despite the general expert consensus on the matter, countless attempts have been made at finding Atlantis." (Dawson & Hayward, 2016)

- ^ Laird, A. (2001). "Ringing the Changes on Gyges: Philosophy and the Formation of Fiction in Plato's Republic". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 121: 12–29. doi:10.2307/631825. JSTOR 631825. S2CID 170951759.

- ^ a b c Luce, John V. (1978). "The Literary Perspective". In Ramage, Edwin S. (ed.). Atlantis, Fact or Fiction?. Indiana University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-253-10482-3.

- ^ Griffiths, J. Gwyn (1985). "Atlantis and Egypt". Historia. 34 (1): 3–28. JSTOR 4435908.

- ^ Görgemanns, Herwig (2000). "Wahrheit und Fiktion in Platons Atlantis-Erzählung". Hermes. 128 (4): 405–419. JSTOR 4477385.

- ^ Zangger, Eberhard (1993). "Plato's Atlantis Account – A Distorted Recollection of the Trojan War". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 12 (1): 77–87. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.1993.tb00283.x.

- ^ Gill, Christopher (1979). "Plato's Atlantis Story and the Birth of Fiction". Philosophy and Literature. 3 (1): 64–78. doi:10.1353/phl.1979.0005. S2CID 170851163.

- ^ Naddaf, Gerard (1994). "The Atlantis Myth: An Introduction to Plato's Later Philosophy of History". Phoenix. 48 (3): 189–209. doi:10.2307/3693746. JSTOR 3693746.

- ^ a b Morgan, K. A. (1998). "Designer History: Plato's Atlantis Story and Fourth-Century Ideology". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 118 (1): 101–118. doi:10.2307/632233. JSTOR 632233. S2CID 162318214.

- ^ Plato's Timaeus is usually dated 360 BC; it was followed by his Critias.

- ^ a b c Ley, Willy (June 1967). "Another Look at Atlantis". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 74–84.

- ^ Plato. "Timaeus". Translated by R. G. Bury. Loeb Classical Library. Section 24e-25a.

- ^ "Atlantis—Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. 29 March 2023.

- ^ Also it has been interpreted that Plato or someone before him in the chain of the oral or written tradition of the report, accidentally changed the very similar Greek words for "bigger than" ("meson") and "between" ("mezon") – Luce, J.V. (1969). The End of Atlantis – New Light on an Old Legend. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 224.

- ^ The name is a back-formation from Gades, the Greek name for Cadiz.

- ^ Plato (360 BCE). "Timaeus". Translated by Benjamin Jowett. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Castleden 2001, p. 164

- ^ Castleden 2001, pp. 156–158.

- ^ Rudberg, G. (1917/2012). Atlantis och Syrakusai, 1917; English: Atlantis and Syracuse, 2012. ISBN 978-3-8482-2822-5

- ^ Nesselrath, HG (2005). 'Where the Lord of the Sea Grants Passage to Sailors through the Deep-blue Mere no More: The Greeks and the Western Seas', Greece & Rome, vol. 52, pp. 153–171 [pp. 161–171].

- ^ Plato. "Timaeus". Perseus Digital Library (in Ancient Greek). Section 24a. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

τὰ γράμματα λαβόντες

- ^ Cameron 2002[full citation needed]

- ^ Castleden 2001, p. 168

- ^ a b Cameron, Alan (1983). "Crantor and Posidonius on Atlantis". The Classical Quarterly. New Series. 33 (1): 81–91. doi:10.1017/S0009838800034315. S2CID 170592886.

- ^ Muck, Otto Heinrich, The Secret of Atlantis, Translation by Fred Bradley of Alles über Atlantis (Econ Verlag GmbH, Düsseldorf-Wien, 1976), Times Books, a division of Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co., Inc., New YorkISBN 978-0-671-82392-4

- ^ Proclus, Commentary on Plato's Timaeus, pp. 117.10–30 (=FGrHist 671 F 1), trans. Taylor, Nesselrath.

- ^ Strabo 2.3.6

- ^ a b Davis, J.L. and Cherry, J.F., (1990) "Spatial and temporal uniformitarianism in LCI: Perspectives from Kea and Melos on the prehistory of Akrotiri" in Hardy, D.A and Renfrew, A.C. (Eds)(1990) "Thera and the Aegean World III, Proceedings of the Third International Conference, Santorini, Greece, 3–9 September 1989" (Thera Foundation)

- ^ a b Castleden, Rodney (1998), "Atlantis Destroyed" (Routledge), p6

- ^ Fitzpatrick-Matthews, Keith. Lost Continents: Atlantis.

- ^ [1] Bibliotheca historica – Diodorus Siculus 4.56.4: "And the writers even offer proofs of these things, pointing out that the Celts who dwell along the ocean venerate the Dioscori above any of the gods, since they have a tradition handed down from ancient times that these gods appeared among them coming from the ocean. Moreover, the country which skirts the ocean bears, they say, not a few names which are derived from the Argonauts and the Dioscori."

- ^ T. Franke, Aristotle and Atlantis, 2012; pp. 131–133

- ^ "Philo: On the Eternity of the World". Earlychristianwritings.com. 2 February 2006. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Lightfoot, translator, The Apostolic Fathers, II, 1885, p. 84, Edited & Revised by Michael W. Holmes, 1989.

- ^ De Camp, LS (1954). Lost Continents: The Atlantis Theme in History, Science, and Literature. New York: Gnome Press, p. 307. ISBN 978-0-486-22668-2

- ^ "Church Fathers: On the Pallium (Tertullian)". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ "ANF06. Fathers of the Third Century: Gregory Thaumaturgus, Dionysius the Great, Julius Africanus, Anatolius, and Minor Writers, Methodius, Arn". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. 1 June 2005. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Cosmas Indicopleustes (2010). The Christian Topography of Cosmas, an Egyptian Monk: Translated from the Greek, and Edited with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-01295-9.

- ^ Roger Pearse. "Cosmas Indicopleustes, Christian Topography (1897) pp. 374–385. Book 12". Tertullian.org. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ^ Donnelly, I (1882). Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, New York: Harper & Bros. Retrieved 6 November 2001, from Project Gutenberg p. 295.

- ^ Feder, KL. Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology, Mountain View, Mayfield 1999. ISBN 978-0-07-811697-1

- ^ a b c Hoopes, John W. (2011). "Mayanism Comes of (New) Age". In Joseph Gelfer (ed.). 2012: Decoding the Counterculture Apocalypse. London: Equinox Publishing. pp. 38–59. ISBN 978-1-84553-639-8.

- ^ Ortelius, Abraham (1596). "Gadiricus". Thesaurus Geographicus. Antwerp: Plantin. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ a b c Callahan, Tim; Friedhoffer, Bob; Pat Linse (2001). "The Search for Atlantis!". Skeptic. 8 (4): 96. ISSN 1063-9330.

- ^ Hoopes, John W. (2011). "Mayanism Comes of (New) Age". In Joseph Gelfer (ed.). 2012: Decoding the Counterculture Apocalypse. London: Equinox Publishing. pp. 38–59 [p. 46]. ISBN 978-1-84553-639-8.

- ^ Evans, R. Tripp (2004). Romancing the Maya: Mexican Antiquity in the American Imagination, 1820–1915. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-292-70247-9.

- ^ Evans, R. Tripp (2004). Romancing the Maya: Mexican Antiquity in the American Imagination, 1820–1915. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 141–146. ISBN 978-0-292-70247-9.

- ^ Brunhouse, Robert L. (1973). In Search of the Maya: The First Archaeologists. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8263-0276-2.

- ^ Donnelly 1941: 192–203

- ^ Williams, Stephen (1991). Fantastic Archaeology: The Wild Side of North American Prehistory. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-0-8122-8238-2.

- ^ Jordan, Paul (2006). "Esoteric Egypt". In Garrett G. Fagan. Archaeological Fantasies. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 23–46. ISBN 978-0-415-30593-8

- ^ Fortune, Dion. "Esoteric Orders and Their Work" (PDF). ourladyisgod.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ a b Edelstein, Dan (2006). "Hyperborean Atlantis: Jean-Sylvain Bailly, Madame Blavatsky, and the Nazi Myth". Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture. 35: 267–291 [p. 268]. doi:10.1353/sec.2010.0055. ISSN 0360-2370. S2CID 144152893.

- ^ Ratner., Paul (26 November 2018). "Why the Nazis were obsessed with finding the lost city of Atlantis". Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ Powell, The Solar System, pp. 25–26. (Ch. 36. "The second Atlantean sub-race: the Tlavatli".)

- ^ Powell, The Solar System, pp. 252–263. (Ch. 39. "Ancient Peru: A Toltec remnant".)

- ^ "Root races". Uranian Wisdom. 11 August 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ Joscelyn Godwin, Arktos: The Polar Myth in Science, Symbolism, and Nazi Survival, Kempton ILL 1996, pp. 37–78.

- ^ Alfred Rosenberg. "Excerpts from "The Myth of the Twentieth Century"". cwporter.com. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "The Theosophical Root Races". Kepher. Archived from the original on 1 September 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ See Tillett, Gregory John Charles Webster Leadbeater (1854–1934), a biographical study. Ph.D. Thesis. University of Sydney, Department of Religious Studies, Sydney, 1986 – p. 985 Archived 30 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Cayce, Edgar Evans (1968). Edgar Cayce on Atlantis. New York and Boston: Grand Central Publishing. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-446-35102-7.

- ^ Runnels, Curtis; Murray, Priscilla (2004). Greece Before History: An Archaeological Companion and Guide. Stanford: Stanford UP. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-8047-4036-4. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ^ J. Annas, Plato: A Very Short Introduction (OUP 2003), p. 42 (emphasis not in the original)

- ^ Timaeus 25e, Jowett translation.

- ^ Feder, KL. Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology, Mountain View, Mayfield 1999, p. 164 ISBN 978-0-07-811697-1

- ^ Collina-Girard, Jacques, L'Atlantide retrouvée: enquête scientifique autour d'un mythe (Paris: Belin – pour la science, 2009).

- ^ Valente Poddighe, Paolo. Atlantide Sardegna: Isola dei Faraoni (Atlantis Sardinia: Island of the Pharaohs). Stampacolor

- ^ Frau, Sergio. Le Colonne d'Ercole. Un'inchiesta. La prima geografia. Tutt'altra storia. Nur Neon 2002

- ^ Evin, Florence (15 August 2015). "Was Sardinia home to the mythical civilisation of Atlantis?". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Zangger, Eberhard (1993). The Flood from Heaven: Deciphering the Atlantis legend. New York: William Morrow and Company.

- ^ James, Peter; Thorpe, Nick (1999). Ancient Mysteries. New York City, New York: Ballantine Books. pp. 16–41. ISBN 978-0-345-43488-3.

- ^ "Plato's Atlantis in South Morocco?". Asalas.org. Archived from the original on 11 December 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ^ Price, Mark (22 July 2022). "Origin of surreal 'Eye of the Sahara' debated — yet again — after NASA shares photo". Miami Herald. Retrieved 6 November 2022.

- ^ Lilley, Harvey (20 April 2007). "The wave that destroyed Atlantis". BBC News. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Bruins, Hendrik J.; et al. (2008). "Geoarchaeological tsunami deposits at Palaikastro (Crete) and the Late Minoan IA eruption of Santorini" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (1): 191–212. Bibcode:2008JArSc..35..191B. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.08.017. hdl:11370/01bb92b9-dc59-47b2-bac7-63ad80afb745. S2CID 43944032. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Afonso, Leoncio (1980). "El mito de la Atlántida". Geografía física de Canarias: Geografía de Canarias (in Spanish). Editorial Interinsular Canaria. p. 11. ISBN 978-84-85543-15-1.

- ^ Rodríguez Hernández, María Jesús (2011). Imágenes de Canarias 1764–1927. Historia y ciencia (in Spanish). Fundación Canaria Orotava. p. 38. ISBN 978-84-614-5110-4.

- ^ a b Sweeney, Emmet (2010). Atlantis: The Evidence of Science. Algora Publishing. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-87586-771-7.

- ^ a b Vidal-Naquet, Pierre (2005). L'Atlantide: Petite histoire d'un mythe platonicien (in French). Belles Lettres. p. 92. ISBN 978-2-251-38071-1.

- ^ Menendez, I., P.G. Silva, M. Martín-Betancor, F.J. Perez-Torrado, H. Guillou, and S. Scaillet, 2009, Fluvial dissection, isostatic uplift, and geomorphological evolution of volcanic islands (Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain) Geomorphology. v. 102, no.1, pp. 189–202.

- ^ Meco J., S. Scaillet, H. Guillou, A. Lomoschitz, J.C. Carracedo, J. Ballester, J.-F. Betancort, and A. Cilleros, 2007, Evidence for long-term uplift on the Canary Islands from emergent Mio–Pliocene littoral deposits. Global and Planetary Change. v. 57, no. 3-4, pp. 222–234.

- ^ Huang, T.C., N.D. Watkins, and L. Wilson, 1979, Deep-sea tephra from the Azores during the past 300,000 years: eruptive cloud height and ash volume estimates. Geological Society of America Bulletin. vol. 90, no. 2, pp. 131–133.

- ^ Dennielou, B. G.A. Auffret, A. Boelaert, T. Richter, T. Garlan, and R. Kerbrat, 1999, Control of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and the Gulf Stream over Quaternary sedimentation on the Azores Plateau. Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série II. Sciences de la Terre et des Planètes. v. 328, no. 12, pp. 831–837.,

- ^ Ferreira, 2005, p. 4

- ^ Ting Yang, et al., 2006, p. 20

- ^ Carlos S. Oliveira; Ragnar Sigbjörnsson; Simon Ólafsson (1–6 August 2004). A Comparative Study on Strong Ground Motion in Two Volcanic Environments: Azores and Iceland (PDF). 13th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ^ G. Queiroz; J. L. Gaspar; J. E. Guest; A. Gomes; M. H. Almeida (16 September 2015). "Eruptive history and evolution of Sete Cidades Volcano, São Miguel Island, Azores". Geological Society, London, Memoirs. 44 (1). Geological Society of London: 87–104. doi:10.1144/M44.7. S2CID 131501147.

- ^ a b Kühne, Rainer W. (June 2004). "A location for Atlantis?". Antiquity. 78 (300). ISSN 0003-598X. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Lovgren, Stefan (19 August 2004). "Atlantis "Evidence" Found in Spain and Ireland". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 20 August 2004.

- ^ Erlingsson, Ulf (11 July 2005). A geographic comparison of Plato's Atlantis and Ireland as a test of the megalithic culture hypothesis. Atlantis Conference. Milos.

- ^ "Swedish academic plays down Atlantis claims". The Irish Times. 19 August 2004. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Finding Atlantis". National Geographic Channel. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ^ Howard, Zach (12 March 2011). "Lost city of Atlantis, swamped by tsunami, may be found". Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Ivar Lissner (1962). The Silent Past: Mysterious and forgotten cultures of the world. Putnam. p. 156.

- ^ Zoe Fox (14 March 2011). "Science Lost No Longer? Researchers Claim to Have Found 'Atlantis' in Spain". Time. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Francisco Ruiz; Manuel Abad; et al. (2008). "The Geological Record of the Oldest Historical Tsunamis in Southwestern Spain" (PDF). Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia. 114 (1): 145–154. ISSN 0035-6883. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2012.

- ^ Owen, Edward (14 March 2011). "Lost city of Atlantis 'buried in Spanish wetlands'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Schulten, Adof (1927). "Tartessos und Atlantis". Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen (in German). 73: 284–288.

- ^ Polidoro, Massimo (November–December 2020). "Atlantis under Ice? Part 1". Skeptical Inquirer. Amherst, New York: Center for Inquiry. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ The Atlantis Blueprint: Unlocking the Ancient Mysteries of a Long-Lost Civilization. Delta; Reprint edition. 28 May 2002. ISBN 978-0-440-50898-4.

- ^ Earth's shifting crust: A key to some basic problems of earth science. Pantheon Books. 1958. ASIN B0006AVEEU.

- ^ Ballingrud, David (17 November 2002). "Underwater world: Man's doing or nature's?". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ Atlantis – The Lost Continent Finally Found Santos, Arysio; Atlantis Publications, August 2005, ISBN 0-9769550-0-8.

- ^ Ramaswamy, Sumathi (2005). The lost land of Lemuria: fabulous geographies, catastrophic histories. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24440-5.

- ^ Smith, O. D. (2016). "The Atlantis Story: An Authentic Oral Tradition?". Shima: The International Journal of Research into Island Cultures. 10(2): 10-17.

- ^ Mauro Tulli, "The Atlantis poem in the Timaeus-Critias", in The Platonic Art of Philosophy, Cambridge University 2013, pp. 269–282

- ^ "The following papyrus, 1359, which Grenfell and Hunt identified as also from the Catalogue, is regarded by C. Robert as part of a separate epic, which he calls Atlantis." Bell, H. Idris, "Bibliography: Graeco-Roman Egypt A. Papyri (1915–1919)", The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 6, No. 2 (Apr., 1920), pp. 119–146.

- ^ P.Oxy. 1359. See Carl Robert (1917): Eine epische Atlantias, Hermes, Vol. 52, No. 3 (Jul., 1917), pp. 477–79.

- ^ Porphyry, Life of Plotinus, 7=35.

- ^ Nesselrath, HG (1998). 'Theopomps Meropis und Platon: Nachahmung und Parodie', Göttinger Forum für Altertumswissenschaft, vol. 1, pp. 1–8.

- ^ Nesselrath, HG (1998). 'Theopomps Meropis und Platon: Nachahmung und Parodie', Göttinger Forum für Altertumswissenschaft, vol. 1, pp. 1–8.

- ^ Heyrick, Thomas (1687). The New Atlantis: A Poem, in Three Books. London: Privately printed. Retrieved 11 June 2024 – via Early English Books Online, University of Michigan Library Digital Collections.

- ^ "Archived online". 1709.

- ^ Nováková, Soňa, pp. 121–6 "Sex and Politics: Delarivier Manley's New Atalantis"

- ^ Online edition. Grosset & Dunlap. April 2022.

- ^ Boris Thomson, Lot's Wife and the Venus of Milo: Conflicting Attitudes to the Cultural Heritage in Modern Russia, Cambridge University 1978, pp. 77–8

- ^ Archived online

- ^ Robert Hughes, Barcelona, London 1992, pp. 341–3

- ^ Isidor Cònsul, "The translations of Verdaguer

- ^ Obras Poeticas, pp. 151–166; there is a translation of canto 8 by Elijah Clarence Hills

- ^ Los Trovadores de México (Barcelona, 1898), pp.383-4

- ^ Joensen, Leyvoy (2002). "Atlantis, Bábylon, Tórshavn: The Djurhuus Brothers and William Heinesen in Faroese Literary History". Scandinavian Studies. 74 (2): 181–204 [esp. 192–4]. JSTOR 40920372.

- ^ "Black Cat poems".

- ^ "Litscape".

- ^ "Poets.org". Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Google Books p. 11

- ^ Gary Catalano, Heaven of Rags, Sydney 1982, Australian Poetry Library Archived 23 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ""Atlantis"".

- ^ Bonnie Costello, "Setting out for Atlantis", from Auden at Work, Palgrave Macmillan 2015, pp. 133–53

- ^ In two parts at Black Cat Poems; part 1 and part 2

- ^ Dryden, J. L. (December 1998). Mona, Queen of Lost Atlantis. Health Research Books. ISBN 978-0-7873-0298-6.

- ^ Archived online, pp. 7–127

- ^ "Archived online". 1895.

- ^ Hathi Trust. The Brooks Company. 1897.

- ^ Pichler, Madeleine (2013). Atlantis als Motiv in der russischen Literatur des 20. Jahrhunderts (PDF) (M.A. thesis). Vienna University. pp. 27–30. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2016.

- ^ Pichler, pp. 37–40.

- ^ There is a performance on YouTube

- ^ Symphony 4, of which there is a performance on YouTube

- ^ Symphony 1, "Atlantis, the sunken city", recorded by the London Philharmonic Orchestra during the 1990s

- ^ A performance on YouTube

- ^ "Presto Classical".

- ^ The Heritage Encyclopedia of Band Music by William H. Rehrig, ed. by Paul Bierley. Westerville OH: Integrity Press, 1991. vol. 2, pp. 655–656

- ^ Beaumont, Antony (2001), in Holden, Amanda (Ed.), The New Penguin Opera Guide, New York: Penguin Putnam. ISBN 0-140-29312-4

- ^ Karas, Joža (1990). Music in Terezín, 1941–1945. Hillsdale, New York: Pendragon Press.

- ^ Unknown author (26 April 1977), "From the archive: Death takes a holiday", The Guardian (London), 26 April 1977; reprinted on 26 April 2014

- ^ Davidson, Pamela (2009). Cultural Memory and Survival: The Russian Renaissance of Classical Antiquity in the Twentieth Century. Studies in Russia and Eastern Europe. Vol. 6. London, UK: School of Slavonic and East European Studies, UCL. pp. 5–15.

- ^ "Flicker".

- ^ "View online".

- ^ Meštrović, Matthew, "Meštrović's American Experience", Journal of Croatian Studies, XXIV, 1983

- ^ "Meštrović Gallery".

- ^ "Brussels Pictures".

- ^ Kunstbus article quoting "Luk van Soom" Archived 16 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Hypothetical Continent – Map of Broken Clear Glass: Atlantis". Robert Smithson. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012.

- ^ "Dia Beacon Gallery". 27 July 2015.

- ^ "Artist's site". Archived from the original on 21 March 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

Further reading

Ancient sources

- Plato, Timaeus, translated by Benjamin Jowett at Project Gutenberg; alternative version with commentary.

- Plato, Critias, translated by Benjamin Jowett at Project Gutenberg; alternative version with commentary.

Modern sources

- Calvo, T., ed. (1997). Interpreting the Timaeus-Critias, Proceedings of the IV. Symposium Platonicum in Granada September 1995. Academia St. Augustin. ISBN 978-3-89665-004-7.

- Castleden, Rodney (2001). Atlantis Destroyed. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-24759-7.

- Forsyth, P. Y. (1980). Atlantis: The Making of Myth. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-0355-7.

- Gill, C. (1980). Plato, The Atlantis Story: Timaeus 17–27 Critias. Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 978-0-906515-59-4.

- Jordan, P. (1994). The Atlantis Syndrome. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3518-0.

- Ramage, E. S., ed. (1978). Atlantis: Fact or Fiction?. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-10482-3.

- Vidal-Naquet, Pierre (2007). The Atlantis Story: A Short History of Plato's Myth. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. ISBN 978-0-85989-805-8.