The Kinks' 1965 US tour

| Tour by the Kinks | |

Poster promoting the band's 6 July concert at the Honolulu International Center | |

| Associated album | Kinks-Size |

|---|---|

| Start date | 18 June 1965 |

| End date | 10 July 1965 |

| No. of shows | 16 |

| The Kinks concert chronology | |

The English rock band the Kinks staged their first concert tour of the United States in June and July 1965. The sixteen concerts comprised the third stage of a world tour, following shows in Australasia, Asia and in the United Kingdom and before later stages in continental Europe. Initially one of the most popular British Invasion groups, the Kinks saw major commercial opportunity in the US, but the resultant tour was plagued with issues between the band, their management, local promoters and the American music unions. Promoters and union officials filed complaints over the Kinks' conduct, prompting the US musicians' union to withhold work permits from the band for the next four years, effectively banning them from US performance.

The programme was in the package-tour format typical of the 1960s, with one show per day, several support acts on the bill and the Kinks' set lasting around 40 minutes. Concerts were characterised by screaming fans and weak sound systems. The US press, which still largely viewed rock music as simple teenage entertainment, generally avoided reporting on the tour. Some shows were poorly attended, owing to a lack of advertising and promotion, leaving local promoters sometimes unable to pay the band the full amount they were due. A payment disagreement led to the band refusing to perform at the Cow Palace near San Francisco, and an argument over a union contract before a television appearance resulted in Ray Davies, the Kinks' bandleader, physically fighting with a union official.

The relationship between Ray and the Kinks' personal manager, Larry Page, was marked by continual friction. Bothered by Ray's behaviour, Page departed to England in the tour's final week, an action that the Kinks viewed as an abandonment. The band's subsequent efforts to dismiss Page led to a protracted legal dispute in English courts. Unable to promote their music in the US via tours or television appearances, the Kinks saw a decline in their American record sales. Cut off from the American music scene, Ray shifted his songwriting approach towards more overt English influences. Ray resolved the ban in early 1969, and the Kinks staged a comeback tour later that year, but they did not achieve regular commercial success in the country again until the late 1970s.

Background

[edit]In April 1965, the Kinks' personal manager Larry Page announced the band's intention to tour the United States. Initially planned to begin on 11 June, the tour would run for three weeks and would be the band's first in the country.[1] The shows formed the third leg of a world tour, following concerts in January and February in Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong and Singapore, and concerts in the United Kingdom in April and May.[2] Page began co-managing the Kinks in November 1963, around two months after the band's two other managers, Grenville Collins and Robert Wace.[3] The resulting three-manager set-up was complicated,[4][5] and it soon became a source of resentment for the Kinks when they saw much of their income going to other people.[6]

After witnessing the enormous commercial success experienced in the US by the Beatles in 1964, Page was hoping to break the Kinks into the American market before the Rolling Stones, who he felt had been underpromoted.[7][nb 1] Like their contemporaries, the Kinks were part of the British Invasion, a cultural phenomenon where British pop acts experienced sudden popularity in the US.[12][13] A second wave of British acts, including the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds and Them,[14] entered the American charts in early 1965,[15] and the Kinks were initially the most popular of these.[14] Two of their earliest US singles – "You Really Got Me" and "All Day and All of the Night", released in September and December 1964, respectively[16] – had each reached the top ten of the Billboard Hot 100 chart, while their first US album was moderately successful,[17] peaking at number 29 in the magazine's Top LPs chart in March 1965.[18] As the Kinks appeared to be on the verge of major American success,[19] the band and their management considered a US tour to be the next pivotal step in their career.[20][21]

From 10 to 14 February 1965, while returning to Britain from the first leg of their world tour, the Kinks visited the US for the first time.[22] The original plan had the band appearing on two musical variety programmes – Hullabaloo in New York and Shindig! in Los Angeles – along with two concert dates, but only the Hullabaloo appearance went ahead.[23] When the band appeared on the programme,[24] they angered trade union officials by initially refusing to sign paperwork with the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (AFTRA), the US performers' union.[23][25] Joining the union was a requirement of the Kinks' appearance,[23][25] but the band were not convinced that it was necessary.[26] Two weeks after the band's visit, their US label Reprise Records issued "Tired of Waiting for You" as a single in the US.[27] It subsequently reached number six on the Billboard Hot 100,[28] making it the Kinks' third consecutive top ten single in the US.[24] To capitalise on the nationwide publicity the band were experiencing,[24] Reprise rushed out a second album in late March, Kinks-Size,[29] which peaked at number 13 in the third week of June,[30] the same week the US tour commenced.[31]

By early 1965, the Kinks had developed a reputation for violence and aggression,[32][33] both on and off the stage.[34] The band's concerts were characterised by hysterical fans, whose swarming attempts occasionally left the group bruised, concussed and with torn clothing.[35][36] On 9 April, a concert in Copenhagen, Denmark, descended into a riot between fans and police;[37] the incident was covered by the Associated Press newswire and reported on in newspapers across the US.[38] The band sometimes broke into physical altercations during rehearsals, recording sessions and concerts; infighting was most common between the brothers Ray and Dave Davies and between Dave and the drummer Mick Avory.[39][40] Tensions within the group were more elevated than usual following a violent intra-band dispute on 19 May at a concert in Cardiff, Wales, where Avory struck Dave in the head with a hi-hat stand.[41] Dave was briefly hospitalised, and the four remaining dates of the band's UK tour were cancelled.[42][43] Britain's national press covered the Cardiff incident in detail, leading to hoteliers across the country imposing an unofficial ban on the Kinks.[44] The band initially considered replacing Avory with a different drummer, but their managers pressurised them into downplaying the incident, both to avoid police charges and to allow them to fulfil their commitments, including the imminent US tour.[20] After agreeing to regroup, the band performed one concert and made four British television appearances in the first week of June.[31]

Repertoire, tour personnel and equipment

[edit]

The US shows were in the package-tour format typical of the 1960s. The Kinks and the Moody Blues were set to be joint headliners,[45] but when the Moody Blues were unable to enter the country after having been denied US visas,[46][47] they were replaced with different acts at various stages of the tour, including the Supremes, the Dave Clark Five and Sonny & Cher.[45] Local groups and musicians performed as support acts, including Paul Peterson, Dick and Dee Dee, the Hollywood Argyles, the Rivieras and Dobie Gray, among others.[48] Rather than headlining at the shows in California on 3 and 4 July, the Kinks instead appeared as one of several support acts for the American rock band the Beach Boys.[49][50][51]

The shows ran for several hours,[52] the Kinks' set usually lasting for around 40 minutes.[53][54] On Page's recommendation, they based their shows around their first hit single "You Really Got Me". To generate anticipation, they played the opening bars of the song at the start of each concert before abruptly switching to a different number. They performed a complete version of the song midway through the set and repeated it during their encore.[53]

The band wore matching red jackets, frilly shirts, black trousers and Chelsea boots,[55] all of which were custom-ordered from Bermans & Nathans, a major theatrical costumier in London.[56] Page commissioned the outfits in April 1964 as part of his early efforts to rework the band's image,[57] providing them with a distinctive look, similar in effect to the collarless suits the Beatles wore in 1963.[56] Though not historically accurate to the Victorian era,[56] the look emphasised the band's Englishness, especially to an American audience who knew little about English culture.[58] The band were regularly taunted by Americans during the tour over their appearance, especially their long hair,[59][60] which, when paired with their outfits, gave them a more androgynous and less masculine appearance than that of other contemporary pop acts.[61][62][nb 2]

Sound quality at the band's shows was poor, as the often weak PA systems at the venues struggled to compete with the loud screams of fans. Drums were typically not miked, and Avory later recalled struggling to hear himself play at larger venues.[64] A local newspaper article describing a show at one of the smaller venues reported that the band's vocals were "lost in an array of electric guitars".[65]

Dave began the tour with his main guitar, a black Guild archtop electric with two Guild humbucking pick-ups and a Bigsby tailpiece,[66] a custom-built instrument originally meant for Beatle George Harrison.[67] The guitar was lost by an airline when the band flew to Los Angeles,[68] and because the band did not travel with spare guitars, Dave was obliged to find a replacement at a local music shop.[69] He bought a 1958 Gibson Flying V, which he debuted on Shindig! on 1 July.[49][70] Dave played the guitar at chest-height, placing his arm through the cut-out V shape at the guitar's base.[67][nb 3]

The Kinks were accompanied on tour by Page and road manager Sam Curtis, who was hired two months earlier, before the band's recent UK tour.[74] Page saw his own role as mainly promotional, dealing with stage management and public relations, while Curtis handled custodial duties, such as organising transport, meals and sleeping arrangements.[75] In the final week of the US tour, California businessman Don Zacharlini stood in as temporary tour manager in Page's place.[49] Collins and Wace, who generally focused on office work,[76] remained in the UK for the duration of the tour.[61][77] The band were regularly visited by their publisher Edward Kassner, who took time to promote Ray's songwriting catalogue; the band's publicist Brian Sommerville and booking agent Arthur Howes arrived three weeks before the start of the tour to perform advance work. The tour was booked through Ken Kendall Associates in New York City.[78]

Tour

[edit]Final preparations

[edit]After announcing the tour, Page made several changes to the itinerary. He announced different dates in press releases before delaying the start by a week to 17 June,[79] something necessitated by Dave's head injury in Cardiff.[80][81] Early plans included different locations, including a Canadian show, probably for Vancouver, on 11 July.[82] By 16 June, five of 16 finalised shows were cancelled, prompting the addition of hastily arranged concerts in downstate Illinois, Denver and Honolulu.[31]

We got the contracts sent from America. These were standard agency contracts. ... I went round to see Ray [Davies], sat there, showed him the contract and said, "Fine, you've got to countersign them with me". And I gave him a fountain pen and I watched him empty it on the floor. ... There was no way he wanted to put pen to paper to do the American tour ...[83]

– Larry Page, the Kinks' personal manager, 1982

The Kinks signed contracts for the tour on 16 June at Denmark Productions,[31] the London offices of Page and Kassner.[84] Among the forms were applications to join the American Federation of Musicians (AFM), the US musicians' union.[31][81] The union's main purpose was to regulate the movement and placement of professional musicians in America,[85] and joining was a requirement for working in the country.[86] Concerned that foreign workers would take away jobs from American citizens, the AFM in 1964 initially opposed allowing any British rock musicians to perform in the US.[87] British groups often found the regulations of the AFM and AFTRA overly complicated,[88] and some complained about the requirements to pay hundreds of dollars in fees for each visit.[89] Ray initially expressed reservations about signing the necessary paperwork;[90] after working a union job as a teenager, he had come to see trade unions as needlessly corrupt and militant.[91] Page instead ascribed Ray's hesitance to his tendency towards prima donna–like behaviour.[90]

Each of the Kinks had held romantic notions about the US since they were young,[26][92] but Ray was apprehensive about visiting the country, having become more cynical after the assassination of US President John F. Kennedy in November 1963.[93] He worried in part how American police would respond to the Kinks' sometimes violent intra-band disputes,[90] especially since only a month had passed since the incident in Cardiff.[93] He was further disappointed by the poor financial returns of the band's February visit and was unhappy about leaving his wife Rasa at home with their first-born child, who was born weeks earlier in mid-May.[94] Ray agreed to go after receiving assurances from his father that he would help Rasa take care of the baby.[95]

Arrival and first week

[edit]| External audio | |

|---|---|

The Kinks departed London at midday on 17 June and arrived in New York City early that afternoon. The same day of their arrival, the band appeared on The Clay Cole Show to promote their latest single "Set Me Free",[31][96] which entered the Hot 100 the week before and peaked a month later at number 23.[97] The tour's first show occurred the following day at the Academy of Music, a cinema in New York City.[31] The appearance was beset by issues; the band were disappointed by the old venue's facilities and the theatre's employees, who showed open contempt to those in the rock and roll business. The venue's marquee initially incorrectly advertised "The Kings", and a dispute arose when the Kinks, the Supremes and the Dave Clark Five realised that promoter Sid Bernstein had promised each group that they would be topping the bill.[98][99] Problems continued at the following day's performance in Philadelphia, where Page was arrested and briefly jailed for failing to pay a local tax as demanded by a union official.[54][100]

The wild, piercing sounds of the four long-haired Englishmen brought the crowd to a near frenzy as it screamed its approval and pushed towards the stage. The "Kinks," who gyrate on stage as if they were all flea bitten, had to be protected by a human barrier formed by Springfield policemen and security guards.[101]

– The State Journal-Register, 24 June

The Kinks' audience, many of whom were teenage girls, were prone to fanatical behaviour.[102][103] Curtis recalled women following the band throughout the tour out of sexual interest, especially for Dave.[104] Upon their arrival in New York, the band were unable to enter their hotel for about two hours owing to a large crowd; and on other nights fans clung to the side of their moving vehicle or smashed its windows with their fists.[103] After fans rushed the Kinks at the conclusion of their concert in Chicago, police and security guarded the stage at a show two nights later in Springfield, Illinois.[101] To keep the fans further at bay during the tour,[102] police escorted the band throughout the day and were posted at their hotel.[105][106]

Tensions among the Kinks remained high during the tour.[107][108] Since the incident in Cardiff, Dave and Avory had generally stopped speaking to one another,[108] and Page later recalled separating the group to prevent more fighting.[61][107] He further recalled that bassist Pete Quaife was generally a calming influence among his bandmates, but he remained hesitant to take sides.[107] Throughout the tour, Page experienced regular issues from Ray, who often pestered his manager to amuse himself.[109][110] Page described Ray as behaving like a prima donna, and Curtis suggested that Ray regularly sought to annoy anyone whose interest in him was entirely financial.[111] While the other Kinks went out to clubs, Ray spent much of his free time during the tour alone in his hotel room, disappointed he was not at home with Rasa and their newborn.[26]

The Kinks' shows received little to no coverage in local newspapers, as most journalists viewed the band and rock music more broadly as simple teenage entertainment.[112] In contrast with the effective publicity work done by the Beatles and their management, the Kinks were aloof with the press in interviews.[113] Ray was apprehensive about his role as the band's frontman and he was typically nervous in front of cameras.[26] The band often tried to make interviewers look foolish or feel uncomfortable, something which regularly drew consternation from Page.[114][nb 4] Band biographer Jon Savage writes that compared to the British Invasion's "packaged pop groups", like the Dave Clark Five and Herman's Hermits, the Kinks instead presented as "brooding, dark, androgynous mutants" whose attitudes seemed anarchic to Middle America.[61] The band later described sometimes feeling resentment from Americans during the tour, especially as they proceeded into the American Midwest, where attitudes skewed more conservative.[105][117][nb 5] Ray further sensed disgust on the part of those in the American music business, whose unhappiness with disruption of their industry by British acts was compounded when the Kinks' appearances were drawing less money than originally expected.[121] A week before the band's 27 June show in Stockton, California, promoter Betty Kaye cancelled the concert because of poor advance-ticket sales,[105] an action she expected to lose her around US$3,500 (equivalent to US$34,000 in 2023).[122][123]

The Kinks were disappointed by the tour's early financial returns, which left them staying in inexpensive hotels and travelling mostly by coach.[26][nb 6] The band and their management experienced regular issues with local promoters, who often looked for reasons to avoid paying the full amount required by contract.[124] Having been hastily arranged only weeks earlier, the band's shows in downstate Illinois were poorly advertised and poorly run,[54] contributing to a growing feeling among the band that the tour was not meeting their original expectations.[54][125][nb 7] The band's 25 June concert in Reno, Nevada, was poorly attended because of both a lack of advertising and its conflicting with the opening day of the popular Annual Reno Rodeo. Kaye offered the band half of the agreed payment upfront, promising them the rest after the next night's performance in Sacramento, California.[64][100] In retaliation, Page threatened to sue her, and the Kinks only performed for 20 minutes rather than the 40 minutes originally contracted. At the Sacramento show, Kaye was further offended when the Kinks played for 45 minutes but filled much of their set with a prolonged version of "You Really Got Me".[105]

Promotional work

[edit]

From 27 June to 2 July, the Kinks had a week off from concerts, during which time they mostly did promotional work in Hollywood, California. The band lip-synched performances on the television programmes Shivaree, The Lloyd Thaxton Show, Shindig! and Dick Clark's variety show Where the Action Is. At the same time, Kassner promoted Ray's songwriting catalogue around Los Angeles. By the end of the week he had secured four agreements, including from Peggy Lee, who recorded "I Go to Sleep" as a single.[121][nb 8] The same week, Page met Cher as she finished sessions for her debut album at Gold Star Studios in Hollywood, and he convinced her to record "I Go to Sleep" as well.[121][nb 9]

Cher's recording inspired Page, who booked studio time for the Kinks at Gold Star on 30 June.[121] The band were normally produced by Shel Talmy, whose contract with Pye Records specified that he was to supervise all of their recording sessions. Talmy anticipated Page attempting to usurp his role and had filed a legal notice before the band left England advising them to not record in the US without him, but the session proceeded anyway.[130] The Kinks were enthusiastic at the prospect of recording in an American studio for the first time, especially after plans to do so the day before at Warner Brothers Studios failed to materialise. During the session, they recorded Ray's composition "Ring the Bells".[121] Page hoped to issue the recording as their next single,[131] but Talmy again served the band legal papers to prevent it, leaving the recording unissued.[121][nb 10]

The Kinks were the featured performers on Shindig! for the week of 1 July, and the band selected "Long Tall Shorty" to play as the show's closing number. Rather than have the band mime to the version they recorded for their first LP, AFM requirements dictated that a new backing track be made, which the show's house band the Shindogs recorded at a separate evening session on 30 June. The Kinks attended the session, but Dave was the only one of them who appeared on the recording, contributing rhythm guitar.[121] Among the Shindogs was lead guitarist James Burton, whom the Kinks were especially excited to meet, having known him for his guitar solos on many of Ricky Nelson's hits; Ray later recalled that getting to play with Burton was both "the biggest thrill" and "the only good thing" to happen during the tour.[121][nb 11]

On 2 July, the Kinks appeared at the Cinnamon Cinder club in North Hollywood for a daytime shoot of Where the Action Is.[49] While waiting beforehand in the band's dressing room,[136] Dave refused to sign a contract presented to the band by AFTRA.[49] The refusal prompted a union official to threaten to have the Kinks banned from ever playing in the US again.[49] After a further exchange of words, a physical altercation occurred between the official and Ray,[49] which ended when Ray punched him in the face.[137] Ray later said the worker taunted the Kinks by calling them "communists", "limey bastards" and "fairies".[137] He also recalled:

I remember a guy came down – they kept on harassing us for various reasons ... and this guy kept going on at me about, "When the Commies overrun Britain you're really going to want to come here, aren't you?" I just turned around and hit him, about three times. I later found out that he was a union official.[138]

Final week

[edit]

Ray's fight with the union official on 2 July marked a low point on the tour for him,[49] a depression exacerbated by the absence of Rasa.[139][140] The following day, after the afternoon soundcheck at the Hollywood Bowl, Ray informed Page that he was not going to perform the evening's show.[49] Advertised as "The Beach Boys Summer Spectacular",[49] the concert had the Kinks billed highest among the Beach Boys' ten support acts.[50][141] Page regarded the concert as the pinnacle of the tour and an opportunity to present the Kinks as a second Beatles, and he later recalled trying to convince Ray to perform: "I spent all day pleading, begging, grovelling – and this was after a very heavy tour ... it was totally degrading for me."[139] Ray demanded of Page that Rasa and Quaife's girlfriend Nicola be flown out to see them, and Page contacted Collins back in London to arrange the flight.[142] Ray agreed to perform,[49] and the concert proceeded as normal in front of around 15,000 concertgoers.[143][144] Rasa and Nicola arrived in Los Angeles after the show and joined the group for the remainder of the tour.[49][145]

After weeks of being agitated by Ray's behaviour, Page lost his patience at the Hollywood Bowl.[146] He abruptly departed back to London on the morning of 4 July.[49][139] In his place, he arranged for the band to be led by both Curtis and temporary tour manager Don Zacharlini, a local businessman who owned a chain of laundromats.[147] Page advised Dave, Quaife and Avory of his intentions but did not tell Ray, who learned of Page's absence later that day. Ray was incensed by what he saw as an abandonment of the band; after expressing his feelings to his bandmates, the group decided that they would extricate Page from their business dealings upon their return to the UK.[49]

The same day as Page's departure, the Kinks arrived at the Cow Palace near San Francisco for an afternoon show as part of "The Beach Boys' Firecracker". The promoter, again Kaye, lost a significant amount of money when only 3,500 tickets were sold out of 14,000. The Kinks demanded to be paid upfront, but a lack of cash receipts meant that she was only able to offer a cheque. In light of their earlier pay disputes with her in Reno and Sacramento, the band refused to perform the San Francisco show.[49]

Despite the absence of Page,[77] the final week of the tour proceeded generally without incident.[148] The band arrived in Hawaii on 5 July and held two concerts in Honolulu the following day,[49] including a show for US Army troops at Schofield Barracks.[149] Ray had expected Hawaii to be overly commercialised, but he was charmed by the islands' quiet beaches; he later named it his best holiday ever,[112][150] and Rasa described her time there with Ray as like a second honeymoon.[151] After an off-day spent in Waikiki, the band flew to Washington state and held three concerts, concluding the tour in Seattle on 10 July.[112][nb 12]

Aftermath

[edit]Return to England and dismissal of Larry Page

[edit]

Quaife and Avory remained in the US for an extra ten days sightseeing southern California with Zacharlini;[112][155] Ray and Dave arrived home in London on 11 July and immediately conveyed their angry feelings about Page to Wace.[112] Page was initially unaware of the others' plans to oust him, and though Ray and Wace continued to be friendly in their interactions with him, the two met with a solicitor on 2 August to begin planning the separation.[156][157] The following day, Ray arrived unannounced at a Sonny & Cher recording session at which Page was present, angrily objecting to the duo recording one of his compositions,[156] "Set Me Free", while also expressing his wish for Page to terminate involvement with the Kinks.[129]

The Kinks resumed their world tour in Sweden on 1 September, accompanied only by Curtis.[158] The following day, Wace and Collins' firm Boscobel Productions served a legal notice advising Page and Kassners' firm Denmark Productions that the Kinks intended to terminate their existing contract.[159][160] Page filed litigation in November over his subsequent remuneration,[161][162] leading to a protracted legal dispute between the two parties in London's High Court in May and June 1967, followed by the Court of Appeal from March to June 1968.[163][164] Key aspects of each of the hearings centred on whether Page's departure to London in the final week of the US tour constituted a legal abandonment, something which generated disagreement among the three justices hearing the appeal.[165][166] Page was only partially successful, when both courts awarded him compensation up to 14 September 1965.[167][168] The management dispute ended on 9 October 1968, when a final appeal filed by Page was rejected.[169][nb 13]

American performance ban

[edit]Following the issues between the Kinks and Betty Kaye in Reno, Sacramento and San Francisco,[100][173] she filed a formal complaint with Local 6,[137] the San Francisco branch of the AFM.[174] Union officials in Los Angeles and likely San Francisco filed further complaints.[173][nb 14] In response, the AFM withheld future work permits from the Kinks,[147] in effect banning the band from future US performance.[177][nb 15]

The last tour we did in America was terrible. We played some dreadful places. If we go again I would want 100 per cent better organisation and facilities. I couldn't bear [another package tour] – really. There are two ways of promoting in the U.S. One is to do a monster tour of the whole country and the other is to do three or more major TV shows which are networked – that's the way I want to do it.[179][180]

– Ray Davies, June 1966

The AFM made no public statements regarding their action against the Kinks,[181] nor did they communicate to the band an explanation or possible duration.[177][181][nb 16] The Kinks hoped to return to the US soon after,[112][182] but four tours booked for between December 1965 and December 1966 were each cancelled a month beforehand after the band proved unable to obtain work visas.[183] Anticipating further visa issues, they declined an invitation to the Monterey International Pop Festival,[184][185] a June 1967 Californian music festival which elevated the American popularity of several acts.[186][187][nb 17] Plans to tour the US in December 1967 and December 1968 similarly fell through after more visa denials.[191]

The AFM's ban on the Kinks persisted for four years.[176] Ray negotiated with the union to lift it when he visited Los Angeles in April 1969.[192] As part of the agreement, the AFM required the Kinks and their management to write apologies to Kaye[193] and refrain from discussing the matter publicly.[194] Over ensuing decades, Ray, Dave and the band's management remained vague in explaining the situation in interviews.[195][nb 18] Asked for comment in December 1969 by Rolling Stone magazine, the union stated that it had no official paperwork regarding a ban on the Kinks but added that the reciprocity agreement between the AFM and the British Musicians' Union allowed either organisation to withhold permits from acts which "behave badly on stage or fail to show for scheduled performances without good reason".[182][198] Other AFM officials subsequently said that the Kinks were banned on the grounds of "unprofessional conduct".[199][nb 19] The biographer Thomas M. Kitts alternatively suggests that the AFM's sanctions against the Kinks were motivated by a desire "to make an example of some young English musicians who, the union believed, were taking work from Americans". Kitts adds that the Kinks proved an easier target than the Rolling Stones, who, despite their presentation as one of teenage rebellion, often remained on agreeable terms with officials and promoters.[147][199][nb 20]

The American ban had a profound effect on me, driving me to write something particularly English in a way which made me look at my own roots rather than American inspirations. I realised that I had a voice of my own that needed to be explored and drawn out.[204]

– Ray Davies, 2004

In later interviews, Ray regularly cited the ban as producing a pivot in his songwriting towards English-focused lyrics.[205] The situation left the Kinks comparatively isolated from American influence and changes in its music scene,[206] guiding the band away from their earlier blues-based riffing towards a distinctly English style.[207][208] While American songwriters explored the emerging drug culture and genre of psychedelia,[209] Ray focused on English musical influences like music hall.[208][210] Ray later suggested that visiting America ended his envy of the country's music,[112] leading him to abandon attempts to "Americanise" his accent while withdrawing into what he later termed "complete Englishness and quaintness".[211]

The American ban hampered the development of the Kinks' career. Unable to promote their music in the US via tours or television appearances, they saw a decline in their American record sales.[212][213] American groups covered Ray's compositions less often after 1965, and those that did generally restricted their selection to British Top Ten hits.[214] The band experienced continued success in the UK, but only two of their singles entered the top 30 of the Billboard Hot 100 while the ban remained active.[215][nb 21] By late 1967, after a string of poor performing singles, American record shops had generally stopped stocking the band's releases.[217] The band steadily lost American fans,[218][219] but they retained a cult following and received favourable coverage from America's nascent underground rock press.[177][217] After the ban was lifted, Reprise and Warner Bros. Records initiated a promotional campaign to re-establish the Kinks' commercial standing before their return tour, held from October to December 1969,[220][221] which the promotional campaign and some contemporary newspapers described as the band's first American tour.[222] Other than their single "Lola",[223] which reached number nine in the US in October 1970,[97] the Kinks did not achieve regular commercial success in the country again until the late 1970s.[224][225]

Critics and journalists often retrospectively identify the American ban as the critical juncture in the Kinks' career.[226] Commentators typically see the ban as essential in shaping the band's underdog and outsider image, especially when compared to most successful British Invasion bands.[227] According to the academic Carey Fleiner, the ban serves as a "rallying cry" for the band's fans when arguing why they do not enjoy the same long-term "multinational corporate brand" as the Beatles or the Rolling Stones.[228]

Set list

[edit]The Kinks played for around 40 minutes,[53][54] but no complete set lists from the US tour are known to band biographers.[48] Below are examples of set lists from the second and fifth legs of the world tour, roughly two months before and three months after the US tour, respectively:[229]

|

30 April 1965, Adelphi Cinema, Slough, UK |

1 October 1965, Hit House, Munich, West Germany

|

Tour dates

[edit]According to the band researcher Doug Hinman, except where noted:[48][nb 22]

| Date (1965) |

City | Venue |

|---|---|---|

| 18 June | New York | Academy of Music |

| 19 June | Philadelphia | Philadelphia Convention Hall |

| 20 June (2 shows) |

Peoria | Exposition Gardens |

| 21 June | Chicago | Arie Crown Theater |

| 22 June | Decatur | Kintner Gymnasium |

| 23 June | Springfield | Illinois State Armory |

| 24 June | Denver | Denver Auditorium Arena |

| 25 June | Reno | Centennial Coliseum |

| 26 June | Sacramento | Sacramento Memorial Auditorium |

(cancelled) |

Stockton | Stockton Memorial Civic Auditorium |

| 3 July | Los Angeles | Hollywood Bowl |

(cancelled) |

Daly City | Cow Palace |

| 6 July (2 shows) |

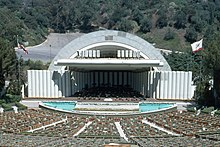

Honolulu | Conroy Bowl |

| Honolulu International Center | ||

| 8 July | Spokane | Spokane Coliseum |

| 9 July | Tacoma | Memorial Fieldhouse |

| 10 July | Seattle | Seattle Center Coliseum |

Note

- The above table includes neither those shows which were cancelled before the tour began nor those dates which were not finalised.[48] The cancelled shows were in Indianapolis, Louisville, Rockford, San Jose and San Diego, planned for 20, 22, 23 June and 2 and 5 July, respectively.[231] Tentative dates planned for 9–16 June but never finalised included Manchester, Wappingers Falls, Boston, Providence, New Haven, Bridgeport, Hartford and Youngstown, as well as Vancouver on 11 July.[31]

Notes

[edit]- ^ By May 1965, the Rolling Stones had toured the US three times,[8] but their only single to reach the US top ten was "Time Is on My Side", which peaked at number six in December 1964.[9] That same month, "Little Red Rooster" reached number one on the British charts,[10] but it was not given a US release.[11]

- ^ When the band appeared on Hullabaloo in February 1965, Ray and Avory angered the show's producers by performing an impromptu cheek-to-cheek dance.[23] Ray later suggested that the outrage stemmed from it being "the first time they had ever seen guys acting like queers on American television".[63]

- ^ The guitar sold poorly when first introduced, but its prime-time appearance with the Kinks generated interest.[71] Gibson resumed manufacturing two years later,[72] and the roughly 100 originals became super-rare as its popularity expanded.[73]

- ^ After it was announced on 11 June that the Beatles were to be awarded MBEs,[115] Ray joked in multiple interviews that he and his bandmates were to receive the medal as well but planned to return it,[114] a joke reported seriously by some American journalists.[104][116]

- ^ Ray recalled that in the tour's final week,[112] a waitress at Spokane's airport complained to police after he kissed his wife in public.[118][119] In a show of solidarity, the other Kinks responded by kissing one another in front of the waitress.[120]

- ^ The Kinks performed in front of 13,000 at the Philadelphia Convention Hall[54] but were only paid a flat fee of $1,000 (equivalent to US$10,000 in 2023), eliciting confusion from Ray.[26][123]

- ^ The Springfield show was organised by future serial killer John Wayne Gacy,[126] then vice-president of the local Jaycees chapter.[54] In 2000, Quaife recounted Gacy inviting the Kinks to his home,[127] a story dismissed by band biographers Nick Hasted and Doug Hinman.[54][128]

- ^ Bobby Rydell recorded "When I See that Girl of Mine" and the San Diego group the Cascades recorded both "I Bet you Won't Stay" and "There's a New World (That's Opening for Me)".[121]

- ^ Page and Sommerville signed with Sonny & Cher to become their European business manager and British publicist, respectively. Page oversaw the duo's first British promotional tour in the first two weeks of August 1965.[129]

- ^ Talmy and Page argued over the issue in public statements and interviews before resolving the disagreement in person on 12 July. "See My Friends" was issued as the band's next single on 30 July. The band re-recorded "Ring the Bells" with Talmy in August, and it appeared on the album The Kink Kontroversy in November.[132]

- ^ A month after the interaction, the Kinks started regularly covering the blues standard "Milk Cow Blues", styling their arrangement after Nelson and Burton's version.[133] Burton also inspired Dave's spontaneous guitar playing style on the band's 1965 single "Till the End of the Day",[134] which they recorded four months later.[135]

- ^ Ray wrote "Holiday in Waikiki" during the tour[152] and composed "I'll Remember" on a harmonica in Seattle.[112][153] Both songs appeared on the band's 1966 album Face to Face.[154]

- ^ Litigation persisted between Ray and Kassner,[169] who continued claim to Ray's songwriting publishing rights.[170] Ray's songwriting earnings from November 1965 on remained in escrow during the legal proceedings,[171] which persisted until the parties reached an out-of-court settlement in October 1970.[172]

- ^ Another formal complaint may have been filed by a Denver radio station's programme director, who characterised the band's behaviour during a record-shop autograph-session as "vulgar, rude, [and] disgusting".[175][176] He subsequently banned the band's songs from the station's airwaves.[175][176]

- ^ Most authors refer to the situation as a "ban", but band biographer Johnny Rogan writes that the withholding of permits is more readily described as a "universal blacklisting".[177] Academic Mark Doyle terms it a "blacklisting" as well.[178]

- ^ In a 2017 interview, Ray instead said that "a few weeks" after the tour, one of the band's agents sent a letter to Wace and Collins explaining that the Kinks had been banned from America and would "never get another work permit".[26]

- ^ Among those who saw increased success after Monterey Pop were the English rock band the Who,[186][187] a group who consciously styled their early music after the Kinks.[188][189] The Kinks were later embarrassed when, during their 1969 North American tour, they were forced to open for the Who.[190]

- ^ In November 1970, while working in an advisory role for Reprise,[196] Los Angeles Times columnist John Mendelsohn wrote that the Kinks had avoided returning to the US after they "made a somewhat less than positive impression" on the AFM.[197]

- ^ In a similar situation, the Kinks' refusal to go on-stage in Copenhagen, Denmark, on 28 September 1966 prompted the local union to ban them there as well.[200][201] The band did not return to Denmark until July 1969.[196]

- ^ Difficulties between the American unions and other British bands persisted;[199][202] the Fortunes and the Yardbirds each cancelled appearances in late 1965 over permit issues with the AFM and AFTRA.[203]

- ^ Though its release received no mention in Billboard,[216] "A Well Respected Man" reached number 13 in February 1966.[97] "Sunny Afternoon" reached number 14 that October.[97]

- ^ Hinman writes that the Kinks had a day off in Chicago on 22 June,[54] but contemporary articles in the Decatur Herald indicate that the band held a concert that night at Kintner Gymnasium in Decatur, Illinois.[65][230]

References

[edit]- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 53, 54.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 44, 45, 54.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 14, 16.

- ^ Kitts 2008, p. 33.

- ^ Fleiner 2017a, pp. 57, 171n57.

- ^ Fleiner 2017a, p. 57.

- ^ Rogan 1984, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Bonanno 1990, pp. 24–26, 30–31, 38–40.

- ^ "The Rolling Stones Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ^ "Little Red Rooster". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ^ Rogan 1984, p. 30.

- ^ Philo 2014, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Roberts 2014, p. 178.

- ^ a b Ward, Stokes & Tucker 1986, pp. 280, 285.

- ^ Hjort 2008, p. 31.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 31, 38.

- ^ Schaffner 1982, pp. 97–98, 111.

- ^ "Billboard Top LPs". Billboard. 6 March 1965. p. 42.

- ^ Ward, Stokes & Tucker 1986, p. 285.

- ^ a b Hinman 2004, p. 56.

- ^ Rogan 1984, p. 45.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 45–46, 48.

- ^ a b c d Hinman 2004, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Rogan 1984, p. 32.

- ^ a b Kitts 2008, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d e f g Alexander, Phil (5 May 2022). "'There is a bullet waiting for all of us.' How getting shot in New Orleans continued The Kinks' complex relationship with America". MOJO. The Collectors' Series: Mod Icons – Part Two: The Kinks – via Apple News+.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 48, 49.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 46, 48.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 51, 52.

- ^ "Billboard Top LPs". Billboard. 19 June 1965. p. 28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hinman 2004, p. 57.

- ^ Hasted 2011, p. 37.

- ^ Savage 2015, p. 55.

- ^ Fleiner 2017a, pp. 3, 52.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Jovanovic 2013, p. 84.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 52–53.

- ^

- Anon. (11 April 1965). "Teen-Ager Riot Puts Lock on Concert Hall". The Tennessean. p. 14-D. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Anon. (11 April 1965). "Tivoli Gardens Close and Teen-Agers Riot". St. Louis Post Dispatch. p. 22A. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Anon. (11 April 1965). "Beatniks Banned After Concert Riot". Oakland Tribune. p. 11. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jovanovic 2013, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Fleiner 2017a, p. 3.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 208–215.

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 55.

- ^ Jovanovic 2013, p. 89.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 208, 210, 213–214.

- ^ a b Hinman 2004, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Rogan 2015, p. 224.

- ^ Hasted 2011, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d Hinman 2004, pp. 57–61.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Hinman 2004, p. 60.

- ^ a b Hjort 2008, p. 42.

- ^ Anon. (12 July 1965). "Fourth of July Beach Boys' Fizzle!: Top Musical Talent Appears in Cow Palace Show Amid Desolation". KEWB: 30. p. 1.

- ^

- Anon. (22 June 1965). "'Kinks' Head Rock 'n' Roll Show Tonight". Decatur Herald. p. 3. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

... the three-hour concert ...

- Myers, Steve (24 June 1965). "Krazy Kids Krave Kooky Kinks". The State Journal-Register. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023 – via NewsBank.

The voices of the 'Kinks' could hardly be heard near the end of the 2½-hour concert as the audience seemed to be content just screaming and looking at the singers.

- Wilson, Marshall (11 July 1965). "Old-Timer Just Gets Buried: 10,000 Dig Rock 'n' Roll". Seattle Daily Times. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023 – via NewsBank.

This music must be good or the 10,000 young voices would have tired of cheering during the long, long hours of yesterday evening in the Seattle Center Coliseum.

- Anon. (22 June 1965). "'Kinks' Head Rock 'n' Roll Show Tonight". Decatur Herald. p. 3. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Rogan 1984, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hinman 2004, p. 58.

- ^ Rogan 2015, p. 141; Kitts 2008, p. 37 and Jovanovic 2013, p. 64: (look); Jackson 2015, p. 80: (worn during US tour).

- ^ a b c Kitts 2008, p. 37.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Fleiner 2017b, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Davies 1996, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Watson, Jean (24 July 1965). "Kinks Playful as Porpoises on California Visit". KRLA Beat. pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c d Savage 1984, p. 51.

- ^ Faulk 2010, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Davies 1995, p. 219, quoted in Faulk 2010, p. 112.

- ^ a b Hasted 2011, p. 52.

- ^ a b Schultz, Judith L. (23 June 1965). "Kinks Concert Draws Over 2,000". Decatur Herald. p. 3. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hunter 2017, p. 81: (began, archtop, pickups); Atkinson 2021, p. 121: (Bigsby).

- ^ a b Atkinson 2021, p. 121.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 59, 60.

- ^ Hunter 2017, p. 81.

- ^ Davies 1996, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Atkinson 2021, pp. 121, 123.

- ^ Atkinson 2021, p. 123.

- ^ Fjestad & Meiners 2007, p. 9.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 54, 56.

- ^ Rogan 1984, pp. 44, 53–54.

- ^ Rogan 1984, p. 44.

- ^ a b Rogan 1984, p. 54.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 56–57, 59.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 53–54, 56.

- ^ Rogan 2015, p. 225.

- ^ a b Hasted 2011, p. 47.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 57, 61.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Rogan 1984, p. 58.

- ^ Roberts 2010, p. 4.

- ^ Rogan 2015, p. 203.

- ^ Roberts 2010, pp. 5–7.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Hasted 2011, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Rogan 1984, p. 43.

- ^ Rogan 2015, p. 54.

- ^ Doyle 2020, p. 68.

- ^ a b Rogan 2015, p. 218.

- ^ Rogan 1984, p. 43: (financial); Hinman 2004, p. 56: (first-born).

- ^ Jovanovic 2013, p. 92.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 222–223.

- ^ a b c d "The Kinks Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Rogan 1984, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 223–224.

- ^ a b c Kitts 2008, p. 60.

- ^ a b Myers, Steve (24 June 1965). "Krazy Kids Krave Kooky Kinks". The State Journal-Register. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023 – via NewsBank.

- ^ a b Davies 1996, p. 81.

- ^ a b Anon. (25 June 1965). "Kinks Manager Arrested: Pete Quaife phones from U.S.". New Musical Express. p. 12.

- ^ a b Rogan 1984, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d Hinman 2004, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Hasted 2011, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Rogan 2015, pp. 224–225.

- ^ a b Rogan 1984, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Rogan 1984, pp. 46, 51–52, 54.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 224–225, 229–232.

- ^ Rogan 1984, pp. 52, 54.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hinman 2004, p. 61.

- ^ Rogan 2015, p. 223.

- ^ a b Rogan 1984, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 197.

- ^ Harada, Wayne (6 July 1965). "Kinks Foursome Believe Beatles Worthy of MBE". The Honolulu Advertiser. p. B5. Archived from the original on 5 March 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jovanovic 2013, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Jovanovic 2013, p. 99.

- ^ Davies 1995, pp. 257–258.

- ^ Fleiner 2017a, p. 92.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hinman 2004, p. 59.

- ^ Flynn, Helen (22 June 1965). "The Arts – Fine and Lively: Theme and Variations". Stockton Record. p. 17. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Rogan 1984, pp. 45–47.

- ^ Black, Johnny (5 May 2022). "The Early Days: Boys Own". MOJO. The Collectors' Series: Mod Icons – Part Two: The Kinks – via Apple News+.

- ^ Hasted 2011, p. 51.

- ^ Black, Johnny (September 2000). "The Kinks: Hellfire Club". MOJO. No. 82. Archived from the original on 22 May 2023 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Hasted 2011, pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b Hinman 2004, p. 62.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 17, 20, 59, 61.

- ^ Jovanovic 2013, p. 97.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 55, 61, 62, 72.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 59, 62, 350.

- ^ Rogan 1998, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 68, 70.

- ^ Rogan 1984, p. 51.

- ^ a b c Roberts 2014, p. 188.

- ^ Savage 1984, p. 52, quoted in Hinman 2004, p. 60.

- ^ a b c Rogan 1984, p. 52.

- ^ Hasted 2011, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Rau, Peggy (5 July 1965). "They Launch 1,000 Squeals". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. p. A9. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Rogan 2015, p. 231.

- ^ Hjort 2008, p. 42: "... attendance is 14,327".

- ^ Champlin, Charles (6 July 1965). "Critic – With Help – Tabs Beach Boys". Los Angeles Times. p. IV–13. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

More than 15,000 people, the vast majority of them youngsters ...

- ^ Hasted 2011, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Rogan 2015, p. 232.

- ^ a b c Kitts 2008, p. 61.

- ^ Rogan 2015, p. 234.

- ^ Rogan 2015, p. 233.

- ^ Fleiner 2017a, pp. 78, 176n54.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 233–234.

- ^ Fleiner 2017a, p. 78.

- ^ Rogan 2015, p. 294.

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 92.

- ^ Kitts 2008, p. 262n14.

- ^ a b Rogan 1984, p. 57.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 236–237, 240.

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 65.

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 66.

- ^ Rogan 1984, pp. 58, 90–94.

- ^ Rogan 1984, pp. 76, 90.

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 69.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 98–101, 112, 114, 116.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 240–241, 319–322, 340–342.

- ^ Rogan 1984, pp. 91–93.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 320–321, 340–342.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 340–342.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 116, 120.

- ^ a b Hinman 2004, p. 116.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 319, 321.

- ^ Miller 2003, p. 10.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 116, 120, 145.

- ^ a b Hinman 2004, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Miller 2012, pp. 116, 321, 323.

- ^ a b Unterberger, Richie (2014). "Dave Davies: Face to Face". Ugly Things. No. 38. pp. 5–21.

- ^ a b c Doyle 2020, p. 69.

- ^ a b c d Rogan 2015, p. 236.

- ^ Doyle 2020, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Altham, Keith (8 July 1966). "Kinks Calm Over No. 1 News". New Musical Express. p. 3 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 86: "Thursday, [June] 30th, [1966]: ... Earlier in the day Ray is interviewed by Keith Altham for NME ..."

- ^ a b Jovanovic 2013, pp. 107–108.

- ^ a b Alterman, Loraine (13 December 1969). "Who Let the Kinks In?". Rolling Stone. No. 48. p. 8.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 66, 69, 80, 85, 93.

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 96.

- ^ Philo 2014, p. 118.

- ^ a b Kitts 2008, p. 84.

- ^ a b Rogan 2015, p. 324.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 213–214.

- ^ MacDonald 2007, p. 165n2.

- ^ Kitts 2008, p. 147.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 107, 122.

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 128.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 59, 128.

- ^ McNeil, Legs (7 November 2017). "Ray Davies Never Wanted to Be a Singer". PleaseKillMe. Archived from the original on 27 November 2022.

Ray Davies: 'There were two or three issues that got intermingled and one I really cannot talk about that I think was the determining factor on the West Coast. ... I'm not angry about it, I just cannot talk about it, for legal reasons. It will emerge one day.'

- ^ Rogan 2015, p. 661.

- ^ a b Hinman 2004, p. 130.

- ^ Mendelsohn, John (8 November 1970). "Kinks Making Exceptional Noise". Los Angeles Times: Calendar. pp. 20–21, 59. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jovanovic 2013, p. 162.

- ^ a b c Roberts 2014, p. 189.

- ^ Rogan 2015, p. 292.

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 90.

- ^ Hjort 2008, p. 66.

- ^

- Roberts 2014, p. 189: (Fortunes);

- Hutchins, Chris (16 October 1965). "Music Capitals of the World". Billboard. p. 28. (Fortunes planning tour in late 1965);

- Russo 2002, pp. 50–51, 54: (Yardbirds);

- The editors of KRLA Beat (2 October 1965). "A Beat Ediorial: Unwanted Visitors". KRLA Beat. p. 2. (Yardbirds).

- ^ Miller 2004, p. 3, quoted in Doyle 2020, p. 70.

- ^ Field 2002, p. 66; Miller 2003, pp. 80–82; Hasted 2011, p. 123.

- ^ Fleiner 2017a, p. 122.

- ^ MacDonald 2007, p. 189n2.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Kinks Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ Rogan 2015, p. 294: (drug culture); Fleiner 2017a, p. 122: (psychedelia).

- ^ Sullivan 2002, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Davies 1995, p. 269, quoted in Hinman 2004, p. 61: ("Americanise"); Rogan 2015, p. 294: ("complete ...").

- ^ Rogan 1984, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Schaffner 1982, p. 98.

- ^ Fleiner 2017a, pp. 144, 191n8.

- ^ Schaffner 1982, p. 111.

- ^ Hinman 2004, p. 68.

- ^ a b Hinman 2004, p. 107.

- ^ Fleiner 2017a, p. 108.

- ^ Jovanovic 2013, p. 108.

- ^ Hasted 2011, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Rogan 2015, pp. 386–388.

- ^

- The Kinks (2014). The Anthology: 1964–1971: "Reprise US Tour Spot Promo" (CD). Sanctuary, Legacy. Event occurs at 0:39. 88875021542. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022.

After five years on Reprise, [the Kinks] arrive in person this fall for their first US tour.

- Hilburn, Robert (17 November 1969). "Kinks Rock Group Due From England". Los Angeles Times. p. IV–23. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

The new album and the group's first national tour may do much to bring the Kinks the recognition the group deserves.

- Johnson, Jared (13 September 1969). "Here's the Real Byrds Again". The Atlanta Constitution. p. 13–T. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

During [the Kinks'] first American tour in October ...

- The Kinks (2014). The Anthology: 1964–1971: "Reprise US Tour Spot Promo" (CD). Sanctuary, Legacy. Event occurs at 0:39. 88875021542. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 137, 142.

- ^ Fleiner 2017a, p. xiv.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 207, 208–209.

- ^ Fleiner 2017a, p. 150.

- ^ Fleiner 2017a, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Fleiner 2017a, pp. 191–192n11.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 54, 66.

- ^ Anon. (22 June 1965). "'Kinks' Head Rock 'n' Roll Show Tonight". Decatur Herald. p. 3. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hinman 2004, pp. 58, 60.

Sources

[edit]- Atkinson, Paul (2021). Amplified: A Design History of the Electric Guitar. Islington: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78914-274-7. Archived from the original on 5 March 2023 – via Google Books.

- Bonanno, Massimo (1990). The Rolling Stones Chronicle: The First Thirty Years. New York City: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-1301-6 – via the Internet Archive.

- Davies, Dave (1996). Kink: An Autobiography. New York City: Hyperion. ISBN 978-0-7868-6149-1 – via the Internet Archive.

- Davies, Ray (1995). X-Ray: The Unauthorised Autobiography. Woodstock, New York: Overlook Press. ISBN 978-0-87951-611-6 – via the Internet Archive.

- Doyle, Mark (2020). The Kinks: Songs of the Semi-Detached. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78914-254-9. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023 – via Google Books.

- Faulk, Barry J. (2010). British Rock Modernism, 1967–1977: The Story of Music Hall in Rock. Farnham: Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-4094-1190-1 – via the Internet Archive.

- Field, Elizabeth (2002). "Skin and Bone, Tea and Scones: Food and Drink Imagery in The Kinks' Music, 1964–1997". In Kitts, Thomas M. (ed.). Living on a Thin Line: Crossing Aesthetic Borders with The Kinks. Rumford, Rhode Island: Desolation Angel Books. pp. 61–67. ISBN 0-9641005-4-1.

- Fjestad, Zachary R.; Meiners, Larry (2007). Gibson Flying V. Bloomington, Minnesota: Blue Book Publications. ISBN 978-1-886768-72-7. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023 – via Google Books.

- Fleiner, Carey (2017a). The Kinks: A Thoroughly English Phenomenon. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-3542-7. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023 – via Google Books.

- Fleiner, Carey (2017b). "'Rosy, Won't You Please Come Home': Family, home and cultural identity in the music of Ray Davies and the Kinks". In Brooks, Lee; Donnelly, Mark; Mills, Richard (eds.). Mad Dogs and Englishness: Popular Music and English Identities. New York City: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 19–35. ISBN 978-1-5013-1127-7. Archived from the original on 1 March 2023 – via Google Books.

- Hasted, Nick (2011). The Story of the Kinks: You Really Got Me. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84938-660-9 – via the Internet Archive.

- Hinman, Doug (2004). The Kinks: All Day and All of the Night: Day-by-Day Concerts, Recordings, and Broadcasts, 1961–1996. San Francisco, California: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-765-3.

- Hjort, Christopher (2008). So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-by-Day 1965–1973. London: Jawbone Press. ISBN 978-1-906002-15-2.

- Hunter, Dave (2017). Ultimate Star Guitars: The Guitars That Rocked the World, Expanded Edition. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-5239-7. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023.

- Jackson, Andrew Grant (2015). 1965: The Most Revolutionary Year in Music. New York City: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4668-6497-9 – via the Internet Archive.

- Jovanovic, Rob (2013). God Save the Kinks: A Biography. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-671-0 – via the Internet Archive.

- Kitts, Thomas M. (2008). Ray Davies: Not Like Everybody Else. New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-97768-5 – via the Internet Archive.

- MacDonald, Ian (2007). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (Third ed.). Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-733-3 – via the Internet Archive.

- Miles, Barry (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8308-3. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023 – via Google Books.

- Miller, Andy (2003). The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society. 33⅓ series. New York City: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-8264-1498-4. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023 – via Google Books.

- Miller, Andy (2004). The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society (Liner notes). The Kinks. Sanctuary Records. SMETD 102.

- Miller, Leta E. (2012). Music and Politics in San Francisco: From the 1906 Quake to the Second World War. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26891-3. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023 – via Google Books.

- Philo, Simon (2014). British Invasion: The Crosscurrents of Musical Influence. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-8627-8. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023 – via Google Books.

- Roberts, Michael (January 2010). "A Working-Class Hero Is Something to Be: The American Musicians' Union's Attempt to Ban the Beatles, 1964". Popular Music. 29 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1017/S0261143009990353. ISSN 0261-1430. JSTOR 40541475. S2CID 159688258. Archived from the original on 4 March 2023 – via JSTOR.

- Roberts, Michael James (2014). Tell Tchaikovsky the News: Rock 'n' Roll, the Labor Question, and the Musicians' Union, 1942–1968. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-7883-9 – via Google Books.

- Rogan, Johnny (1984). The Kinks: The Sound and the Fury. London: Elm Tree Books. ISBN 0-241-11308-3.

- Rogan, Johnny (1998). The Complete Guide to the Music of the Kinks. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-6314-6.

- Rogan, Johnny (2015). Ray Davies: A Complicated Life. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-1-84792-317-2 – via the Internet Archive.

- Russo, Greg (2002). Yardbirds: The Ultimate Rave-Up (Fourth ed.). Floral Park, New York: Crossfire Publications. ISBN 978-0-9648157-8-0.

- Savage, Jon (1984). The Kinks: The Official Biography. London: Faber and Faber Limited. ISBN 978-0-571-13407-6 – via the Internet Archive.

- Savage, Jon (2015). 1966: The Year the Decade Exploded. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-27762-9 – via the Internet Archive.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1982). The British Invasion: From the First Wave to the New Wave. New York City: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-055089-6 – via Google Books.

- Sullivan, Patricia Gordon (2002). "'Let's Have a Go at It': The British Musical Hall and The Kinks". In Kitts, Thomas M. (ed.). Living on a Thin Line: Crossing Aesthetic Borders with The Kinks. Rumford, Rhode Island: Desolation Angel Books. pp. 80–99. ISBN 0-9641005-4-1.

- Ward, Ed; Stokes, Geoffrey; Tucker, Ken, eds. (1986). Rock of Ages: The Rolling Stone History of Rock & Roll. New York City: Fireside. ISBN 978-0-671-63068-3 – via the Internet Archive.

External links

[edit]- Premium High Resolution Photos of the Kinks in the US in 1965 at Getty Images