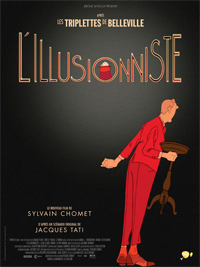

The Illusionist (2010 film)

| The Illusionist | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| French | L'Illusionniste |

| Directed by | Sylvain Chomet |

| Written by | Sylvain Chomet |

| Based on | The Illusionist by Jacques Tati |

| Produced by | Sally Chomet Bob Last |

| Starring | Jean-Claude Donda Eilidh Rankin |

| Edited by | Sylvain Chomet |

| Music by | Sylvain Chomet |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Pathé Distribution (France) Warner Bros. Entertainment UK (United Kingdom)[1] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 79 minutes[2] |

| Countries | France United Kingdom |

| Languages | French English Gaelic |

| Budget | $17 million[3] |

| Box office | $6 million[3] |

The Illusionist (French: L'Illusionniste) is a 2010 animated film written and directed by Sylvain Chomet. The film is based on an unproduced script written by French mime, director and actor Jacques Tati in 1956. Controversy surrounds Tati's motivation for the script, which was written as a personal letter to his estranged eldest daughter, Helga Marie-Jeanne Schiel, in collaboration with his long-term writing partner Henri Marquet, between writing for the films Mon Oncle and Play Time.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

The main character is an elderly version of Tati, with hints of his character Monsieur Hulot. The plot revolves around a struggling illusionist who visits an isolated community and meets a young lady who is convinced that he is a real magician.[10] Chomet relocated the film, originally intended by Tati to be set in Czechoslovakia, to Scotland in the late 1950s.[10][11] According to the director, "It's not a romance, it's more the relationship between a dad and a daughter."[12] Sony's US press kit declares that the "script for The Illusionist was originally written by French comedy genius and cinema legend Jacques Tati as a love letter from a father to his daughter, but never produced".[13] The film received acclaim from critics, and was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, losing to Pixar's Toy Story 3.

The Illusionist was the last film to be distributed by Pathé theatrically in the United Kingdom before being shut down in 2009[citation needed] and focusing as a solo production company on British films starting in 2013 up until their shut down in November 2023.

Plot

[edit]In 1959 Paris, an out-of-work illusionist packs his belongings, including an ill-tempered rabbit, and moves to London. Unable to compete with modern entertainment such as rock and roll, he plies his trade at smaller gatherings in bars, cafés, and parties. He accepts the invitation of a drunken party patron to visit a remote Scottish island, where he entertains the locals. Staying in a room above the pub, he meets a girl, Alice, who is captivated by his illusions and kindness, including a gift of red shoes.

Alice believes the downtrodden performer possesses genuine magical powers, and follows him to Edinburgh, where he performs at a modest theatre. They share a room in a run-down guest house favoured by other fading performers. The illusionist sleeps on a couch, and the girl keeps busy by cleaning and cooking food that she shares with the neighbours. The girl's affections even tame the rabbit, but the illusionist's increasingly meagre wages, spent on gifts for Alice, lead him to pawn his magic kit and secretly take on demeaning jobs.

Alice attracts the affection of a handsome young man. After the illusionist sees them walking together, he leaves her with money and a note stating "Magicians are not real". He also releases the rabbit on Arthur's Seat, where it soon meets other rabbits. As Alice moves in with her boyfriend, the illusionist departs on a train hauled by a locomotive bearing the number 4472. On the train, he performs one last simple magic trick for a child.

Production

[edit]According to the 2006 reading of the script at the London Film School introduced by Chomet, "The great French comic Jacques Tati wrote the script of The Illusionist and intended to make it as a live action film with his daughter".[14] Catalogued in the Centre National de la Cinématographie archives under the impersonal moniker "Film Tati Nº 4",[15] the script was passed to Chomet by the caretakers of Tati's oeuvre, Jérôme Deschamps and Macha Makeïeff after Chomet's previous film The Triplets of Belleville was premiered at the 2003 Cannes Film Festival.[16] Chomet has said that Tati's youngest daughter, Sophie Tatischeff, had suggested an animated film when Chomet was seeking permission to use a clip from Tati's 1949 film Jour de fête as she did not want an actor to play her father.[10] Sophie Tatischeff died on 27 October 2001, almost two years before the 11 June 2003 French release of The Triplets of Belleville.

Animation

[edit]The film was made at Chomet's Edinburgh film studio, Django Films, by an international group of animators directed by Paul Dutton, including Sydney Padua, Greg Manwaring and Jacques Muller.[17][11] It was estimated to cost around £10 million and was funded by Pathé Pictures, but in a February 2010 press conference, Chomet said that it had ended up costing only $17 million (£8.5 million in early 2008).[3] The Herald says 180 creatives were involved, 80 of whom had previously worked on The Triplets of Belleville.[18] In The Scotsman, Chomet cites 300 people and 80 animators.[19] The film was primarily animated in Scottish Studios in Edinburgh (Django Films) and Dundee (ink.digital), with further animation done in Paris and London. The animation scenes set in Paris were executed at Neomis Animation studio, where the animation department was directed by Antoine Antin and the clean-up department by Grégory Lecocq. Around 5% of the work (mainly inbetweening and clean-up) was completed in South Korea.

Django Films was originally established with the intention to establish itself in the filmmaking scene with both animation and live action, however, the company is being dismantled. Django was beset with production difficulties, first losing funding for its first animated feature, Barbacoa. It then failed to secure funding for a BBC project that had been labelled "The Scottish Simpsons".[20] Chomet was then fired from the directorial duties of The Tale of Despereaux by Gary Ross.[21][22] Django Films were very far from employing the 250 artists that it would have been required for the project, an estimated figure reported by Scotland on Sunday in 2005.[23]

Motives for the script

[edit]Controversy has dogged The Illusionist,[24][25][26] with it being reported that "Tati was inspired to write the story in an attempt to reconcile with his eldest daughter, Helga Marie-Jeanne Schiel, whom he had abandoned when she was a baby. And although she's still alive today and may in fact be his only direct living relative, she is nowhere mentioned in the dedications, which has seriously annoyed some".[27]

In January 2010, The Guardian published the article "Jacques Tati's lost film reveals family's pain" stating, "In 2000, the screenplay was handed over to Chomet by Tati's daughter, Sophie Tatischeff, two years before her death. Now, however, the family of Tati's illegitimate and estranged eldest child, Helga Marie-Jeanne Schiel, who lives in the north-east of England, are calling for the French director to give her credit as the true inspiration for the film. The script of L'illusionniste, they say, was Tati's response to the shame of having abandoned his first child [Schiel] and it remains the only public recognition of her existence. They accuse Chomet of attempting to airbrush out their painful family legacy again."[28]

On 26 May 2010, renowned film critic Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times published a lengthy letter from Jacques Tati's middle grandson, Richard McDonald, that pinpointed historical events in the private life of Jacques Tati that the family believe were his remorseful, melancholy inspiration to write, yet never make, L'Illusionniste.[29]

Chomet has a different opinion about the film's origins, although acknowledging: "I never got to meet Sophie, or even speak to her about the script."[30][31] Chomet said, "I think Tati wrote the script for Sophie Tatischeff. I think he felt guilty that he spent too long away from his daughter when he was working."[32]

In a June 2010 interview for The National, Chomet gave his personal reasons for his attraction to the script: "I have two young children, a four-year-old and a two-year-old. But I also have a daughter who is 17 whom I don't live with because I separated from her mother. She was 12 when I started the project and you can feel things changing."[33] This appears to mirror the regret of a broken paternal relationship that Tati had with his own daughter Helga Marie-Jeanne Schiel. Of the story, Chomet commented that he "fully understood why [Tati] had not brought [The Illusionist] to the screen. It was too close to him, and spoke of things he knew only too well, preferring to hide behind the figure of Monsieur Hulot".[34]

Having corresponded with Tati's grandson, former Tati colleague and Chicago Reader film reviewer Jonathan Rosenbaum published an article entitled "Why I can't write about The Illusionist" in which he wrote, "Even after acknowledging that Chomet does have a poetic flair for composing in long shot that's somewhat Tatiesque, I remain skeptical about the sentimental watering-down of his art that Chomet is clearly involved with, which invariably gives short shrift to the more radical aspects of his vision". With McDonald being quoted saying, "My grandmother and all his stage acquaintances during the 1930s/40s always maintained that [Tati] was a great colleague as a friend and artist; he unfortunately just made a massive mistake that because of the time and circumstances he was never able to correctly address. I am sure his remorse hung heavy within him and it is for this reason that I believe Chomet's adaptation of l'Illusionniste does a great discredit to the artist that was Tati."[35]

Release

[edit]The first footage from the film was shown at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival.[36] The film premiered at the Berlinale festival in February 2010.[37][38] The film opened the 2010 Edinburgh International Film Festival on 16 June.[39]

Pathé Distribution managed distribution for France and the UK, and distribution deals were secured for Lithuania (ACME Film), Japan (Klockworx), Italy (Cinema 11), Greece (Nutopia), the United States (Sony Pictures Classics), Benelux (Paradiso), Russia and the Middle East (Phars Film).[40][41] The first official trailer for the film was in Russian and was released on 13 March 2010.[42] The film was released in France on 16 May 2010.[43]

The Illusionist was then released on DVD by Pathé through 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment in 2011. As of 2021, Warner Bros. Home Entertainment UK is currently re-printing under licence from Pathé. It was also then released on Japanese home media by Walt Disney Studios Japan through the Ghibli Museum Library.[44]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film opened in 84 French cinemas. According to Box Office Mojo, the film released in France on 16 June 2010 entered the box office chart at #8, with a revenue of €485,030 ($600,099) in the first weekend.[45]

The Illusionist opened in the United Kingdom in 42 cinemas (August 2010). It entered the UK box office at #15, with revenue of £161,900 one place behind Disney's Tinker Bell and the Great Fairy Rescue, the chart dominated by Sylvester Stallone's The Expendables which grossed £3,910,596 in revenue in its first weekend of release.[46]

Critical response

[edit]As of October 2021[update], the film holds a 90% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 134 reviews with an average rating of 8/10. Its critical consensus states: "An engrossing love letter to fans of adult animation, The Illusionist offers a fine antidote to garish mainstream fare."[47] It also has a score of 82 out of 100 on Metacritic, based on 31 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[48]

In Télérama, Cécile Mury gave the film a rating of four stars out of five. Mury compared it to the director's previous feature film: "This Illusionist is as tender and contemplative as the Triplets were farcical and uneasy. But we find the oblique look, the talent that is particular of Sylvain Chomet. ... This world of yesterday fleets between realism and poetry."[49] Christophe Carrière of L'Express was not fully convinced by Chomet's directing, finding the story clever, but "blunted when Chomet lets himself be submerged by Tati's melancholy, delivering more of a homage to a master than a personal adaption. Nevertheless, it is otherwise a beautiful work, with impeccable graphics and provides some stunning sequences (based on carnivorous rabbit stew ...). One would have liked a little bit more, that's all."[50]

Jonathan Meville of The Scotsman wrote: "Edinburgh's skyline has never looked so good, and if the city didn't exist it would be hard to believe somewhere so beautiful was real: if locals aren't inspired to take a walk up North Bridge or down Victoria Street after this, they never will be."[51] Whilst also in The Scotsman Alistair Harkness commented that "Once you strip away the overwhelming wow factor of the film's design, the absence of strong characterisation ensures the end result is bleaker and less affecting than was probably intended".[52]

Tati's biographer, David Bellos, reviewing The Illusionist in Senses of Cinema was highly critical of Chomet's adaptation stating "the film is a disaster". "The great disappointment for me and I think for all viewers is that what Chomet does with the material is… well, nothing. The story he tells is no more than the sketchily sentimental plotline of L'Illusionniste. It's really very sad. All that artistry, all that effort, and all that money… for this".[53]

Reviewing The Illusionist in The New Yorker, Richard Brody commented "Sylvain Chomet (The Triplets of Belleville) has directed an animated adaptation of Jacques Tati's 1956 screenplay, with none of Tati's visual wit or wild invention". "Chomet reduces Tati's vast and bilious comic vision to cloying sentimentality. The result is a cliché-riddled nostalgia trip".[54]

Roger Ebert in his review wrote, "However much it conceals the real-life events that inspired it, it lives and breathes on its own, and as an extension of the mysterious whimsy of Tati". Calling it the "magically melancholy final act of Jacques Tati's career", he gave it four stars out of four.[55]

Accolades

[edit]The film won the 2010 European Film Awards[56] and was nominated at the 68th Golden Globe Awards[57] for Best Animated Feature Film. On 25 February 2011, The Illusionist won the first César Award for Best Animated Feature.

It was nominated for Best Animated Feature Film in the 83rd Academy Awards, but lost to Toy Story 3; and an Annie Award for Best Animated Feature, losing to How to Train Your Dragon.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Illusionist: Interview with Sylvain Chomet". August 2010. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "L'ILLUSIONNISTE (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. 26 May 2010. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ a b c The Illusionist at Box Office Mojo

- ^ "In the Works: A black and white doc about shades of grey" Archived 26 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine by Alison Willmore. 02-21-2007. The Independent Eye film blog

- ^ "Cut The Cute" by Ian Johns (17 February 2007) in The Times

- ^ FIC123. "Jacques Tati Deux Temps Trois Mouvements". Fic123cultuurbox.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Chomet Tackles Tati Script" Archived 11 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine Time Out. New York. Stefanou Eleni Stefanou (2007)

- ^ "La postérité de M. Hulot" Archived 16 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, David Bellos (2008-03-25)

- ^ "Jacques Tati Deux Temps Trois Mouvements" Archived 30 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Matthieu Orlean (8 May 2009). Cinémathèque Française

- ^ a b c Pendreigh, Brian (22 June 2007) "Chomet's Magic Touch Archived 7 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine." The Guardian.

- ^ a b Scots animation? That rings a belle (Scotland on Sunday)

- ^ Comic genius Tati returns to screen in cartoon version of lost screenplay The Times by Brian Pendreigh, 2004-04-23

- ^ "Sony Classics The Illusionist Press Kit, 2010" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ London Film School (LFS), Scenario 3 Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 2005-12-19

- ^ "Tati meets Chomet in The Illusionist". Theplayground.co.uk. 28 May 2012. Archived from the original on 5 August 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ Cuomo, Antonio (17 February 2010). "Sylvain Chomet racconta The Illusionist" [Chomet tells The Illusionist]. Movieplayer.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ IMDB Archived 23 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 6 November 2018

- ^ "Why Sylvain Chomet chose Scotland for the movie magic of The Illusionist" Archived 27 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Matheou, Demetrios. The Herald. 15 June 2010

- ^ "Interview: Sylvain Chomet, film director" Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Ramaswamy, Chitra. The Scotsman. 14 June 2010

- ^ unknown (17 December 2006). "Scotlands Simpsons The Clan". Martinfrost.ws. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ "Name Game: A Tale of Acknowledgment for "Despereaux" Cieply Michael and Solomon Charles (2008,09,27) | New York Times". The New York Times. 27 September 2008. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ Published on Thursday 18 February 2010 09:02 (18 February 2010). ""New animated film depicting Edinburgh in the 50s hailed as a masterpiece". Edinburgh News. 18 February 2010". Edinburghnews.scotsman.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Animation World Network (19 September 2005). ""Chomets' Studio Draws Animators to Scotland. DeMott Rick" (2005-09-19) Animation World Network". Awn.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ "Jacques Tatis ode to his illegitimate daughter". 2010-06-16 Daily Telegraph. Accessed 2010-08-19

- ^ Roger Ebert's Journal; "The secret of Jacques Tati" 2010-05. Accessed 2010-08-19 Archived 22 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Sylvain Chomet: the trials of making "The Illusionist Archived 27 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine, "Time Out Magazine. Accessed 2010-08-19

- ^ "Illusions of grandeur". Irish Independent. 21 August 2010.

- ^ Vanessa Thorpe, arts and media correspondent (31 January 2010). ""Jacques Tati's lost film reveals family's pain". Guardian article 2010-01-31". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ The secret of Jacques Tati. "Roger Ebert's Journal; "The secret of Jacques Tati" 2010-05". Blogs.suntimes.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ The National article (UAE) "His master’s voice: a cartoon homage to Jaques Tati" 15 June 2010. Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2010-08-19

- ^ Edinburgh Film Festival article Archived 21 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 2010-08-19

- ^ "Why Sylvain Chomet chose Scotland over Hollywood". Gibbons, Fiachra. The Guardian. 10 June 2010. Accessed 2010-08-19

- ^ The National article Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 2010-08-19

- ^ BoDoi Comic blog (French) Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 2010-08-19

- ^ "Why I Can't Write about The Illusionist". Rosenbaum, Jonathan. 16 January 2011. Accessed 2011-01-16

- ^ Cannes to get glimpse of Studio Pathé's Illusionist Kemp, Stuart. The Hollywood Reporter. 13-05-2008 Archived 25 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Berlinale press release". Berlinale.de. Archived from the original on 24 January 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ "A Definite, Credible Premiere Date for 'The Illusionist'". Gather.com. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ "EIFF conjures up The Illusionist for Opening Gala". Edfilmfest.org.uk. Archived from the original on 11 April 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ Macnab, Geoffrey (23 February 2010). ""The Illusionist leads brisk EFM sales for Studio Pathé", Screen Daily. 23 February 2010". Screendaily.com. Archived from the original on 25 November 2024. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ (in Russian) Ружье, банк и разряд по бегу Archived 20 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Gazeta. 17 February 2010

- ^ L'illusionniste (4 June 2012). "Movie Trailer". Afisha.ru. Archived from the original on 22 March 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ "L'Illusionniste". AlloCiné. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ^ ""Illusionist" Japanese Site". Archived from the original on 20 January 2011. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "France Box Office, June 16–20, 2010". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 7 July 2010. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ^ UK film Council, 22 August 2010

- ^ "The Illusionist (2010)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ "The Illusionist". Metacritic.

- ^ Mury, Cécile (19 June 2010). "L'Illusionniste". Télérama (in French). Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ Carrière, Christophe (15 June 2010). "L'illusionniste, plus un hommage qu'une adaptation". L'Express (in French). Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ Meville, Jonathan (18 June 2010). "Film review: The Illusionist ****". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Harkness, Alistair (18 June 2010). "EIFF reviews: The Illusionist ****". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ The Illusionist by David Bellos Archived 3 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine. 2010-10-11. Senses of Cinema. Accessed 2010-10-11

- ^ Brody, Richard (26 December 2010) "The New Yorker Archived 30 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine"

- ^ "The Illusionist". Chicago Sun-Times. 12 January 2011. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (21 September 2010). "Three nominees for the Best Animated Feature Film prize". Cineuropa. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ "68th Golden Golbes". 16 January 2011. Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

External links

[edit]- Official website (US)

- Official website (Pathé)

- The Illusionist at IMDb

- The Illusionist at AllMovie

- The Illusionist at Box Office Mojo

- The Illusionist at Rotten Tomatoes

- Press conference with Chomet from Berlinale (main content starts at 5:35 in video)

- 2010 films

- 2010 animated films

- 2010 comedy-drama films

- 2010s American films

- 2010s British films

- 2010s English-language films

- 2010s French animated films

- 2010s French-language films

- Animated coming-of-age films

- Animated film controversies

- Animated films set in Edinburgh

- Animated films set in the 1950s

- British animated comedy films

- British animated drama films

- British comedy-drama films

- British coming-of-age films

- English-language comedy-drama films

- European Film Awards winners (films)

- Films about magic and magicians

- Films directed by Sylvain Chomet

- Films set in 1959

- Films set in hotels

- French animated comedy films

- French animated drama films

- French comedy-drama films

- French coming-of-age films

- Jacques Tati

- Pathé films

- Scottish Gaelic-language films

- Sony Pictures Classics animated films

- Warner Bros. animated films

- Warner Bros. films