The Gold-Bug

| "The Gold-Bug" | |

|---|---|

| Short story by Edgar Allan Poe | |

| |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Short story |

| Publication | |

| Published in | Philadelphia Dollar Newspaper |

| Media type | Print (Periodical) |

| Publication date | June 21, 1843 |

"The Gold-Bug" is a short story by American writer Edgar Allan Poe published in 1843. The plot follows William Legrand, who becomes fixated on an unusual gold-colored bug he has discovered. His servant Jupiter fears that Legrand is going insane and goes to Legrand's friend, an unnamed narrator, who agrees to visit his old friend. Legrand pulls the other two into an adventure after deciphering a secret message that will lead to a buried treasure.

The story, set on Sullivan's Island, South Carolina, is often compared with Poe's "tales of ratiocination" as an early form of detective fiction. Poe became aware of the public's interest in secret writing in 1840 and asked readers to challenge his skills as a code-breaker. He took advantage of the popularity of cryptography as he was writing "The Gold-Bug", and the success of the story centers on one such cryptogram. Modern critics have judged the characterization of Legrand's servant Jupiter as racist, especially because of his dialect speech.

Poe submitted "The Gold-Bug" as an entry to a writing contest sponsored by the Philadelphia Dollar Newspaper. His story won the grand prize and was published in three installments, beginning in June 1843. The prize also included $100 (equivalent to $3,270 in 2023), probably the largest single sum that Poe received for any of his works. An instant success, "The Gold-Bug" was the most popular and widely read of Poe's prose works during his lifetime. It also helped popularize cryptograms and secret writing.

Plot summary

[edit]

William Legrand has relocated from New Orleans to Sullivan's Island, South Carolina after losing his family fortune, and has brought his African-American servant Jupiter with him. The story's narrator, Legrand's friend and physician, visits him one evening to see an unusual scarab-like bug he has found. The bug's weight and lustrous appearance convince Jupiter that it is made of pure gold. Legrand has lent it to an officer stationed at the nearby Fort Moultrie, but he draws a sketch of it for the narrator, with markings on the carapace that resemble a skull. As they discuss the bug, Legrand becomes particularly focused on the sketch and carefully locks it in his desk for safekeeping. Confused, the narrator takes his leave for the night.

One month later, Jupiter visits the narrator on behalf of his master and asks him to come immediately, fearing that Legrand has been bitten by the bug and gone insane. Once they arrive on the island, Legrand insists that the bug will be the key to restoring his lost fortune. He leads them on an expedition to a particular tree on the mainland and has Jupiter climb it until he finds a skull nailed at the end of one branch. At Legrand's direction, Jupiter drops the bug through one eye socket and Legrand paces out to a spot where the group begins to dig. Finding nothing there, the three return to the tree and Legrand repositions the peg he had used to mark the spot where the bug landed. He paces out from it to a new area, which yields two skeletons and a chest filled with gold coins and jewelry when the group resumes digging. They estimate the total value at $1.5 million (equivalent to $49.1 million in 2023), but even that figure proves to be below the actual worth when they eventually sell the items.

Legrand explains that on the day he found the bug on the mainland coastline, Jupiter had picked up a scrap piece of parchment to wrap it up. Legrand kept the scrap and used it to sketch the bug for the narrator; in so doing, though, he noticed traces of invisible ink, revealed by the heat of the fire burning on the hearth. The parchment proved to contain a cryptogram, which Legrand deciphered as a set of directions for finding a treasure buried by the infamous pirate Captain Kidd. The final step involved dropping a slug or weight through the left eye of the skull in the tree; their first dig failed because Jupiter mistakenly dropped the bug through the right eye instead. Legrand muses that the skeletons may be the remains of two members of Kidd's crew, who buried the chest and were then killed to silence them.

The cryptogram

[edit]The story involves cryptography with a detailed description of a method for solving a simple substitution cipher using letter frequencies. The encoded message is:

53‡‡†305))6*;4826)4‡.)4‡);80 6*;48†8¶60))85;1‡(;:‡*8†83(88) 5*†;46(;88*96*?;8)*‡(;485);5*† 2:*‡(;4956*2(5*-4)8¶8*;40692 85);)6†8)4‡‡;1(‡9;48081;8:8‡1 ;48†85;4)485†528806*81(‡9;48 ;(88;4(‡?34;48)4‡;161;:188;‡?;

The decoded message with spaces, punctuation, and capitalization is:

A good glass in the bishop's hostel in the devil's seat

forty-one degrees and thirteen minutes

northeast and by north

main branch seventh limb east side

shoot from the left eye of the death's-head

a bee line from the tree through the shot fifty feet out.

Legrand determined that the "bishop's hostel" referred to a group of rocks and cliffs on the mainland, where he found a narrow ledge that roughly resembled a chair (the "devil's seat"). Using a telescope and sighting at the given bearing and elevation, he spotted something white among the branches of a large tree; this proved to be the skull through which a weight had to be dropped from the left eye in order to find the treasure.

Analysis

[edit]"The Gold-Bug" includes a simple substitution cipher. Though he did not invent "secret writing" or cryptography (he was probably inspired by an interest in Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe[1]), Poe certainly popularized it during his time. To most people in the 19th century, cryptography was mysterious and those able to break the codes were considered gifted with nearly supernatural ability.[2] Poe had drawn attention to it as a novelty over four months in the Philadelphia publication Alexander's Weekly Messenger in 1840. He had asked readers to submit their own substitution ciphers, boasting he could solve all of them with little effort.[3] The challenge brought about, as Poe wrote, "a very lively interest among the numerous readers of the journal. Letters poured in upon the editor from all parts of the country."[4] In July 1841, Poe published "A Few Words on Secret Writing"[5] and, realizing the interest in the topic, wrote "The Gold-Bug" as one of the few pieces of literature to incorporate ciphers as part of the story.[6] Poe's character Legrand's explanation of his ability to solve the cipher is very like Poe's explanation in "A Few Words on Secret Writing".[7]

The actual "gold-bug" in the story is not a real insect. Instead, Poe combined characteristics of two insects found in the area where the story takes place. The Callichroma splendidum, though not technically a scarab but a species of longhorn beetle (Cerambycidae), has a gold head and slightly gold-tinted body. The black spots noted on the back of the fictional bug can be found on the Alaus oculatus, a click beetle also native to Sullivan's Island.[8]

Poe's depiction of the African servant Jupiter is often considered stereotypical and racist. Jupiter is depicted as superstitious and so lacking in intelligence that he cannot tell his left from his right.[9] Poe scholar Scott Peeples summarizes Jupiter, as well as Pompey in "A Predicament", as a "minstrel-show caricature".[10] Leonard Cassuto, called Jupiter "one of Poe's most infamous black characters", emphasizes that the character has been manumitted but refuses to leave the side of his "Massa Will". He sums up Jupiter by noting, he is "a typical Sambo: a laughing and japing comic figure whose doglike devotion is matched only by his stupidity".[11] Poe probably included the character after being inspired by a similar one in Sheppard Lee (1836) by Robert Montgomery Bird, which he had reviewed.[12] Black characters in fiction during this time period were not unusual, but Poe's choice to give him a speaking role was. Critics and scholars, however, question if Jupiter's accent was authentic or merely comic relief, suggesting it was not similar to accents used by blacks in Charleston but possibly inspired by Gullah.[13]

Though the story is often included amongst the short list of detective stories by Poe, "The Gold-Bug" is not technically detective fiction because Legrand withholds the evidence until after the solution is given.[14] Nevertheless, the Legrand character is often compared to Poe's fictional detective C. Auguste Dupin[15] due to his use of "ratiocination".[16][17][18] "Ratiocination", a term Poe used to describe Dupin's method, is the process by which Dupin detects what others have not seen or what others have deemed unimportant.[19]

Publication history and reception

[edit]

Poe originally sold "The Gold-Bug" to George Rex Graham for Graham's Magazine for $52 (equivalent to $1,700 in 2023) but asked for it back when he heard about a writing contest sponsored by Philadelphia's Dollar Newspaper.[20] Incidentally, Poe did not return the money to Graham and instead offered to make it up to him with reviews he would write.[21] Poe won the grand prize; in addition to winning $100, the story was published in two installments on June 21 and June 28, 1843, in the newspaper.[22] His $100 payment from the newspaper may have been the most he was paid for a single work.[23] Anticipating a positive public response, the Dollar Newspaper took out a copyright on "The Gold-Bug" prior to publication.[24]

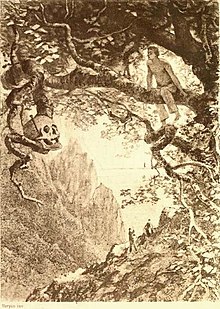

The story was republished in three installments in the Saturday Courier in Philadelphia on June 24, July 1, and July 8; the last two appeared on the front page and included illustrations by F. O. C. Darley.[25] Further reprintings in United States newspapers made "The Gold-Bug" Poe's most widely read short story during his lifetime.[22] By May 1844, Poe reported that it had circulated 300,000 copies,[26] though he was probably not paid for these reprints.[27] It also helped increase his popularity as a lecturer. One lecture in Philadelphia after "The Gold-Bug" was published drew such a large crowd that hundreds were turned away.[28] As Poe wrote in a letter in 1848, it "made a great noise."[29] He would later compare the public success of "The Gold-Bug" with "The Raven", though he admitted "the bird beat the bug".[30]

The Public Ledger in Philadelphia called it "a capital story".[24] George Lippard wrote in the Citizen Soldier that the story was "characterised by thrilling interest and a graphic though sketchy power of description. It is one of the best stories that Poe ever wrote."[31] Graham's Magazine printed a review in 1845 which called the story "quite remarkable as an instance of intellectual acuteness and subtlety of reasoning".[32] Thomas Dunn English wrote in the Aristidean in October 1845 that "The Gold-Bug" probably had a greater circulation than any other American story and "perhaps it is the most ingenious story Mr. POE has written; but... it is not at all comparable to the 'Tell-tale Heart'—and more especially to 'Ligeia'".[33] Poe's friend Thomas Holley Chivers said that "The Gold-Bug" ushered in "the Golden Age of Poe's Literary Life".[34]

The popularity of the story also brought controversy. Within a month of its publication, Poe was accused of conspiring with the prize committee by Philadelphia's Daily Forum.[26] The publication called "The Gold-Bug" an "abortion" and "unmitigated trash" worth no more than $15 (equivalent to $491 in 2023).[35] Poe filed for a libel lawsuit against editor Francis Duffee. It was later dropped[36] and Duffee apologized for suggesting Poe did not earn the $100 prize.[37] Editor John Du Solle accused Poe of stealing the idea for "The Gold-Bug" from "Imogine; or the Pirate's Treasure", a story written by a schoolgirl named Miss Sherburne.[38]

"The Gold-Bug" was republished as the first story in the Wiley & Putnam collection of Poe's Tales in June 1845, followed by "The Black Cat" and ten other stories.[39] The success of this collection inspired[40] the first French translation of "The Gold-Bug", published in November 1845 by Alphonse Borghers in the Revue Britannique[41] under the title, "Le Scarabée d'or", becoming the first literal translation of a Poe story into a foreign language.[42] In the French version, the enciphered message remained in English, with a parenthesized translation supplied alongside its solution. The story was translated into Russian from that version two years later, marking Poe's literary debut in that country.[43] In 1856, Charles Baudelaire published his translation of the tale in the first volume of Histoires extraordinaires.[44] Baudelaire was very influential in introducing Poe's work to Europe and his translations became the definitive renditions throughout the continent.[45]

Influence

[edit]

"The Gold-Bug" inspired Robert Louis Stevenson in his novel about treasure-hunting, Treasure Island (1883). Stevenson acknowledged this influence: "I broke into the gallery of Mr. Poe... No doubt the skeleton [in my novel] is conveyed from Poe."[46]

"The Gold-Bug" also inspired Leo Marks to become interested in cryptography at age 8 when he found the book in his father’s bookshop at 84 Charing Cross Road.[citation needed] Marks would go on to lead Britain’s code-breaking efforts during World War Two as a member of the Special Operations Executive (SOE).[citation needed]

Poe played a major role in popularizing cryptograms in newspapers and magazines in his time period[2] and beyond. William F. Friedman, America's foremost cryptologist, initially became interested in cryptography after reading "The Gold-Bug" as a child—interest that he later put to use in deciphering Japan's PURPLE code during World War II.[47] "The Gold-Bug" also includes the first use of the term cryptograph (as opposed to cryptogram).[48]

Poe had been stationed at Fort Moultrie from November 1827 through December 1828 and utilized his personal experience at Sullivan's Island in recreating the setting for "The Gold-Bug".[49] It was also here that Poe first heard the stories of pirates like Captain Kidd.[50] The residents of Sullivan's Island embrace this connection to Poe and have named their public library after him.[51] Local legend in Charleston says that the poem "Annabel Lee" was also inspired by Poe's time in South Carolina.[52] Poe also set part of "The Balloon-Hoax" and "The Oblong Box" in this vicinity.[50]

O. Henry alludes to the stature of "The Gold-Bug" within the buried-treasure genre in his short story "Supply and Demand". One character learns that the main characters are searching for treasure, and he asks them if they have been reading Edgar Allan Poe. The title of Richard Powers' 1991 novel The Gold Bug Variations is derived from "The Gold-Bug" and from Bach's composition Goldberg Variations, and the novel incorporates part of the short story's plot.[53]

Adaptations

[edit]The story proved popular enough in its day that a stage version opened on August 8, 1843.[54] The production was put together by Silas S. Steele and was performed at the American Theatre in Philadelphia.[55] The editor of the Philadelphia newspaper The Spirit of the Times said that the performance "dragged, and was rather tedious. The frame work was well enough, but wanted filling up".[56]

In film and television, an adaptation of the work appeared on Your Favorite Story on February 1, 1953 (Season 1, Episode 4). It was directed by Robert Florey with the teleplay written by Robert Libott. A later adaptation of the work appeared on ABC Weekend Special on February 2, 1980 (Season 3, Episode 7). This version was directed by Robert Fuest with the teleplay written by Edward Pomerantz.[57] A Spanish feature film adaptation of the work appeared in 1983 under the title En busca del dragón dorado. It was written and directed by Jesús Franco using the alias "James P. Johnson".[58]

"The Gold Bug" episode on the 1980 ABC Weekend Special series starred Roberts Blossom as Legrand, Geoffrey Holder as Jupiter, and Anthony Michael Hall. It won three Daytime Emmy Awards: 1) Outstanding Children's Anthology/Dramatic Programming, Linda Gottlieb (executive producer), Doro Bachrach (producer); 2) Outstanding Individual Achievement in Children's Programming, Steve Atha (makeup and hair designer); and, 3) Outstanding Individual Achievement in Children's Programming, Alex Thomson (cinematographer). It was a co-production of Learning Corporation of America.[59]

References

[edit]- ^ Rosenheim 1997, p. 13

- ^ a b Friedman, William F. (1993), "Edgar Allan Poe, Cryptographer", On Poe: The Best from "American Literature", Durham, NC: Duke University Press, pp. 40–41, ISBN 0-8223-1311-1

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 152

- ^ Hutchisson 2005, p. 112

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 61

- ^ Rosenheim 1997, p. 2

- ^ Rosenheim 1997, p. 6

- ^ Quinn 1998, pp. 130–131

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 206

- ^ Peeples, Scott. The Afterlife of Edgar Allan Poe. Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2004: 97. ISBN 1-57113218-X

- ^ Cassutto, Leonard. The Inhuman Race: The Racial Grotesque in American Literature and Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997: 160. ISBN 978-0-231-10336-7

- ^ Bittner 1962, p. 184

- ^ Weissberg, Liliane. "Black, White, and Gold", Romancing the Shadow: Poe and Race, J. Gerald Kennedy and Liliane Weissberg, eds. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001: 140–141. ISBN 0-19-513711-6

- ^ Haycraft, Howard. Murder for Pleasure: The Life and Times of the Detective Story. New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, 1941: 9.

- ^ Hutchisson 2005, p. 113

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 130

- ^ Stashower 2006, p. 295

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 135

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 74

- ^ Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. The Literary History of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co., 1906: 239.

- ^ Bittner 1962, p. 185

- ^ a b Sova 2001, p. 97

- ^ Hoffman, Daniel. Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe. Louisiana State University Press, 1998: 189. ISBN 0-8071-2321-8

- ^ a b Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 419

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 392

- ^ a b Meyers 1992, p. 136

- ^ Hutchisson 2005, p. 186

- ^ Stashower 2006, p. 252

- ^ Quinn 1998, p. 539

- ^ Hutchisson 2005, p. 171

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 420

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 567

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, pp. 586–587

- ^ Chivers, Thomas Holley. Life of Poe, Richard Beale Davis, ed. E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1952: 36.

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, pp. 419–420

- ^ Meyers 1992, pp. 136–137

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 421

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 422

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 540

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 298

- ^ Salines, Emily. Alchemy and Amalgam: Translation in the Works of Charles Baudelaire. Amsterdam-New York: Rodopi, 2004: 81–82. ISBN 90-420-1931-X

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 585

- ^ Silverman 1991, p. 320

- ^ Salines, Emily. Alchemy and Amalgam: Translation in the Works of Charles Baudelaire. Amsterdam-New York: Rodopi, 2004: 82. ISBN 90-420-1931-X

- ^ Harner, Gary Wayne (1990), "Edgar Allan Poe in France: Baudelaire's Labor of Love", in Fisher IV, Benjamin Franklin (ed.), Poe and His Times: The Artist and His Milieu, Baltimore: The Edgar Allan Poe Society, p. 218, ISBN 0-9616449-2-3

- ^ Meyers 1992, p. 291

- ^ Rosenheim 1997, p. 146

- ^ Rosenheim 1997, p. 20

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 98

- ^ a b Poe, Harry Lee. Edgar Allan Poe: An Illustrated Companion to His Tell-Tale Stories. New York: Metro Books, 2008: 35. ISBN 978-1-4351-0469-3

- ^ Urbina, Ian. "Baltimore Has Poe; Philadelphia Wants Him". The New York Times. September 5, 2008: A10.

- ^ Crawford, Tom. "The Ghost by the Sea Archived 2012-05-10 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- ^ "Genetic Coding and Aesthetic Clues: Richard Powers's 'Gold Bug Variations.'". Mosaic. Winnipeg. December 1, 1998.[dead link]

- ^ Bittner 1962, p. 186

- ^ Sova 2001, p. 268

- ^ Thomas & Jackson 1987, p. 434

- ^ ""ABC Weekend Specials" The Gold Bug (1980)". IMDb.

- ^ IMDb: En busca del dragón dorado

- ^ The Gold Bug. IMDB.

Sources

[edit]- Bittner, William (1962), Poe: A Biography, Boston: Little, Brown and Company

- Hutchisson, James M. (2005), Poe, Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 1-57806-721-9

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1992), Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy, Cooper Square Press, ISBN 0-8154-1038-7

- Quinn, Arthur Hobson (1998), Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-5730-9

- Rosenheim, Shawn James (1997), The Cryptographic Imagination: Secret Writing from Edgar Poe to the Internet, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-5332-6

- Silverman, Kenneth (1991), Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance, New York: Harper Perennial, ISBN 0-06-092331-8

- Sova, Dawn B. (2001), Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z, New York: Checkmark Books, ISBN 0-8160-4161-X

- Stashower, Daniel (2006), The Beautiful Cigar Girl: Mary Rogers, Edgar Allan Poe, and the Invention of Murder, New York: Dutton, ISBN 0-525-94981-X

- Thomas, Dwight; Jackson, David K. (1987), The Poe Log: A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe, 1809–1849, Boston: G. K. Hall & Co., ISBN 0-7838-1401-1

External links

[edit]- "The Gold-Bug" – Full text from the Dollar Newspaper, 1843 (with two illustrations by F. O. C. Darley)

- The Gold-Bug – Introduction to Cryptography – The story, how to solve it, and Poe's essay on secret writing, on Cipher Machines and Cryptology

- "The Gold-Bug" from the University of Virginia Library

- The Works of Edgar Allan Poe, Volume 1 at Project Gutenberg — includes "The Gold-Bug"

- "The Gold-Bug" with annotated vocabulary at PoeStories.com

- Publication history of "The Gold-Bug" at the Edgar Allan Poe Society

- William B. Cairns (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

The Gold-Bug public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Gold-Bug public domain audiobook at LibriVox