G-spot

| G-spot | |

|---|---|

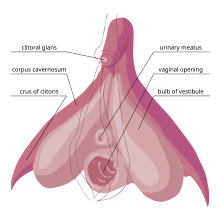

Drawing of the female internal sexual anatomy. The G-spot (6) is reportedly located 5–8 cm (2–3 in) into the vagina, at the side of the urethra with the paraurethral glands (10). | |

| Anatomical terminology |

The G-spot, also called the Gräfenberg spot (for German gynecologist Ernst Gräfenberg), is characterized as an erogenous area of the vagina that, when stimulated, may lead to strong sexual arousal, powerful orgasms and potential female ejaculation.[1] It is typically reported to be located 5–8 cm (2–3 in) up the front (anterior) vaginal wall between the vaginal opening and the urethra and is a sensitive area that may be part of the female prostate.[2][3]

The existence of the G-spot has not been proven, nor has the source of female ejaculation.[4][5] Although the G-spot has been studied since the 1940s,[2] disagreement persists over its existence as a distinct structure, definition and location.[4][6][7] The G-spot may be an extension of the clitoris, which together may be the cause of orgasms experienced vaginally.[7][8][9] Sexologists and other researchers are concerned that women may consider themselves to be dysfunctional if they do not experience G-spot stimulation, and emphasize that not experiencing it is normal.[5]

Theorized structure

Location

Two primary methods have been used to define and locate the G-spot as a sensitive area in the vagina: self-reported levels of arousal during stimulation, and stimulation of the G-spot leading to female ejaculation.[6] Ultrasound technology has also been used to identify physiological differences between women, and changes to the G-spot region during sexual activity.[10][11]

The location of the G-spot is typically reported as being about 50 to 80 mm (2 to 3 in) inside the vagina, on the front wall.[2][12] For some women, stimulating this area creates a more intense orgasm than clitoral stimulation.[11] The G-spot area has been described as needing direct stimulation, such as two fingers pressed deeply into it.[13] Attempting to stimulate the area through sexual penetration, especially in the missionary position, is difficult because of the particular angle of penetration required.[2]

Vagina and clitoris

Women usually need direct clitoral stimulation in order to orgasm,[15][16] and G-spot stimulation may be best achieved by using both manual stimulation and vaginal penetration.[2] A yoni massage also includes manual stimulation of the G-spot.[17]

Sex toys are available for G-spot stimulation. One common sex toy is the specially-designed G-spot vibrator, which is a phallic vibrator that has a curved tip and attempts to make G-spot stimulation easy.[18] G-spot vibrators are made from the same materials as regular vibrators, ranging from hard plastic, rubber, silicone, jelly, or any combination of them.[18] The level of vaginal penetration when using a G-spot vibrator depends on the woman, because women's physiology is not always the same. The effects of G-spot stimulation when using the penis or a G-spot vibrator may be enhanced by additionally stimulating other erogenous zones on a woman's body, such as the clitoris or vulva as a whole. When using a G-spot vibrator, this may be done by manually stimulating the clitoris, including by using the vibrator as a clitoral vibrator, or, if the vibrator is designed for it, by applying it so that it stimulates the head of the clitoris, the rest of the vulva and the vagina simultaneously.[18]

A 1981 case study reported that stimulation of the anterior vaginal wall made the area grow by fifty percent and that self-reported levels of arousal/orgasm were deeper when the G-spot was stimulated.[19][20] Another study, in 1983, examined eleven women by palpating the entire vagina in a clockwise fashion, and reported a specific response to stimulation of the anterior vaginal wall in four of the women, concluding that the area is the G-spot.[21][22] In a 1990 study, an anonymous questionnaire was distributed to 2,350 professional women in the United States and Canada with a subsequent 55% return rate. Of these respondents, 40% reported having a fluid release (ejaculation) at the moment of orgasm, and 82% of the women who reported the sensitive area (Gräfenberg spot) also reported ejaculation with their orgasms. Several variables were associated with this perceived existence of female ejaculation.[23]

Some research suggests that G-spot and clitoral orgasms are of the same origin. Masters and Johnson were the first to determine that the clitoral structures surround and extend along and within the labia. Upon studying women's sexual response cycle to different stimulation, they observed that both clitoral and vaginal orgasms had the same stages of physical response, and found that the majority of their subjects could only achieve clitoral orgasms, while a minority achieved vaginal orgasms. On this basis, Masters and Johnson argued that clitoral stimulation is the source of both kinds of orgasms,[24][25] reasoning that the clitoris is stimulated during penetration by friction against its hood.[26]

Researchers at the University of L'Aquila, using ultrasonography, presented evidence that women who experience vaginal orgasms are statistically more likely to have thicker tissue in the anterior vaginal wall.[11] The researchers believe these findings make it possible for women to have a rapid test to confirm whether or not they have a G-spot.[27] Professor of genetic epidemiology, Tim Spector, who co-authored research questioning the existence of the G-spot and finalized it in 2009, also hypothesizes thicker tissue in the G-spot area; he states that this tissue may be part of the clitoris and is not a separate erogenous zone.[28]

Supporting Spector's conclusion is a study published in 2005 which investigates the size of the clitoris – it suggests that clitoral tissue extends into the anterior wall of the vagina. The main researcher of the studies, Australian urologist Helen O'Connell, asserts that this interconnected relationship is the physiological explanation for the conjectured G-spot and experience of vaginal orgasms, taking into account the stimulation of the internal parts of the clitoris during vaginal penetration. While using MRI technology, O'Connell noted a direct relationship between the legs or roots of the clitoris and the erectile tissue of the "clitoral bulbs" and corpora, and the distal urethra and vagina. "The vaginal wall is, in fact, the clitoris," said O'Connell. "If you lift the skin off the vagina on the side walls, you get the bulbs of the clitoris – triangular, crescental masses of erectile tissue."[8] O'Connell et al., who performed dissections on the female genitals of cadavers and used photography to map the structure of nerves in the clitoris, were already aware that the clitoris is more than just its glans and asserted in 1998 that there is more erectile tissue associated with the clitoris than is generally described in anatomical textbooks.[12][25] They concluded that some females have more extensive clitoral tissues and nerves than others, especially having observed this in young cadavers as compared to elderly ones,[12][25] and therefore whereas the majority of females can only achieve orgasm by direct stimulation of the external parts of the clitoris, the stimulation of the more generalized tissues of the clitoris via intercourse may be sufficient for others.[8]

French researchers Odile Buisson and Pierre Foldès reported similar findings to those of O'Connell's. In 2008, they published the first complete 3D sonography of the stimulated clitoris, and republished it in 2009 with new research, demonstrating the ways in which erectile tissue of the clitoris engorges and surrounds the vagina. On the basis of this research, they argued that women may be able to achieve vaginal orgasm via stimulation of the G-spot because the highly innervated clitoris is pulled closely to the anterior wall of the vagina when the woman is sexually aroused and during vaginal penetration. They assert that since the front wall of the vagina is inextricably linked with the internal parts of the clitoris, stimulating the vagina without activating the clitoris may be next to impossible.[10][29][30][31] In their 2009 published study, the "coronal planes during perineal contraction and finger penetration demonstrated a close relationship between the root of the clitoris and the anterior vaginal wall". Buisson and Foldès suggested "that the special sensitivity of the lower anterior vaginal wall could be explained by pressure and movement of clitoris's root during a vaginal penetration and subsequent perineal contraction".[10][30]

Female prostate

In 2001, the Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology accepted female prostate as a second term for the Skene's gland, which is believed to be found in the G-spot area along the walls of the urethra. The male prostate is biologically homologous to the Skene's gland;[32] it has been unofficially called the male G-spot because it can also be used as an erogenous zone.[1][33]

Regnier de Graaf, in 1672, observed that the secretions (female ejaculation) by the erogenous zone in the vagina lubricate "in agreeable fashion during coitus". Modern scientific hypotheses linking G-spot sensitivity with female ejaculation led to the idea that non-urine female ejaculate may originate from the Skene's gland, with the Skene's gland and male prostate acting similarly in terms of prostate-specific antigen and prostate-specific acid phosphatase studies,[5][34] which led to a trend of calling the Skene's glands the female prostate.[34] Additionally, the enzyme PDE5 (involved with erectile dysfunction) has additionally been associated with the G-spot area.[35] Because of these factors, it has been argued that the G-spot is a system of glands and ducts located within the anterior (front) wall of the vagina.[13] A similar approach has linked the G-spot with the urethral sponge.[36][37]

Clinical significance

G-spot amplification (also called G-spot augmentation or the G-Shot) is a procedure intended to temporarily increase pleasure in sexually active women with normal sexual function, focusing on increasing the size and sensitivity of the G-spot. G-spot amplification is performed by attempting to locate the G-spot and noting measurements for future reference. After numbing the area with a local anesthetic, human engineered collagen is then injected directly under the mucosa in the area the G-spot is concluded to be in.[13][38]

A position paper published by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists in 2007 warns that there is no valid medical reason to perform the procedure, which is not considered routine or accepted by the College; and it has not been proven to be safe or effective. The potential risks include sexual dysfunction, infection, altered sensation, dyspareunia, adhesions and scarring.[13] The College position is that it is untenable to recommend the procedure.[39] The procedure is also not approved by the Food and Drug Administration or the American Medical Association, and no peer-reviewed studies have been accepted to account for either safety or effectiveness of this treatment.[40]

Society and culture

General skepticism

In addition to general skepticism among gynecologists, sexologists and other researchers that the G-spot exists,[4][5][6][7] a team at King's College London in late 2009 suggested that its existence is subjective. They acquired the largest sample size of women to date – 1,800 – who are pairs of twins, and found that the twins did not report a similar G-spot in their questionnaires. The research, headed by Tim Spector, documents a 15-year study of the twins, identical and non-identical. According to the researchers, if one identical twin reported having a G-spot, it was more likely that the other would too, but this pattern did not materialize.[5][10] Study co-author Andrea Burri believes: "It is rather irresponsible to claim the existence of an entity that has never been proven and pressurise women and men too."[41] She stated that one of the reasons for the research was to remove feelings of "inadequacy or underachievement" for women who feared they lacked a G-spot.[42] Researcher Beverly Whipple dismissed the findings, commenting that twins have different sexual partners and techniques, and that the study did not properly account for lesbian or bisexual women.[43]

Petra Boynton, a British scientist who has written extensively on the G-spot debate, is also concerned about the promotion of the G-spot leading women to feel "dysfunctional" if they do not experience it. "We're all different. Some women will have a certain area within the vagina which will be very sensitive, and some won't — but they won't necessarily be in the area called the G spot," she stated. "If a woman spends all her time worrying about whether she is normal, or has a G spot or not, she will focus on just one area, and ignore everything else. It's telling people that there is a single, best way to have sex, which isn't the right thing to do."[44]

Nerve endings

G-spot proponents are criticized for giving too much credence to anecdotal evidence, and for questionable investigative methods; for instance, the studies which have yielded positive evidence for a precisely located G-spot involve small participant samples.[4][6] While the existence of a greater concentration of nerve endings at the lower third (near the entrance) of the vagina is commonly cited,[1][5][9][45] some scientific examinations of vaginal wall innervation have shown no single area with a greater density of nerve endings.[5][6]

Several researchers also consider the connection between the Skene's gland and the G-spot to be weak.[6][46] The urethral sponge, however, which is also hypothesized as the G-spot, contains sensitive nerve endings and erectile tissue.[36][37] Sensitivity is not determined by neuron density alone: other factors include the branching patterns of neuron terminals and cross or collateral innervation of neurons.[47] While G-spot opponents argue that because there are very few tactile nerve endings in the vagina and that therefore the G-spot cannot exist, G-spot proponents argue that vaginal orgasms rely on pressure-sensitive nerves.[4]

Clitoral and other anatomical debates

The G-spot having an anatomical relationship with the clitoris has been challenged by Vincenzo Puppo, who, while agreeing that the clitoris is the center of female sexual pleasure, disagrees with Helen O'Connell and other researchers' terminological and anatomical descriptions of the clitoris. He stated, "Clitoral bulbs is an incorrect term from an embryological and anatomical viewpoint, in fact the bulbs do not develop from the phallus, and they do not belong to the clitoris". He says that clitoral bulbs "is not a term used in human anatomy" and that vestibular bulbs is the correct term, adding that gynecologists and sexual experts should inform the public with facts instead of hypotheses or personal opinions. "[C]litoral/vaginal/uterine orgasm, G/A/C/U spot orgasm, and female ejaculation, are terms that should not be used by sexologists, women, and mass media", he said, further commenting that the "anterior vaginal wall is separated from the posterior urethral wall by the urethrovaginal septum (its thickness is 10–12 mm)" and that the "inner clitoris" does not exist. "The female perineal urethra, which is located in front of the anterior vaginal wall, is about one centimeter in length and the G-spot is located in the pelvic wall of the urethra, 2–3 cm into the vagina", Puppo stated. He believes that the penis cannot come in contact with the congregation of multiple nerves/veins situated until the angle of the clitoris, detailed by Georg Ludwig Kobelt, or with the roots of the clitoris, which do not have sensory receptors or erogenous sensitivity, during vaginal intercourse. He did, however, dismiss the orgasmic definition of the G-spot that emerged after Ernst Gräfenberg, stating that "there is no anatomical evidence of the vaginal orgasm which was invented by Freud in 1905, without any scientific basis".[48]

Puppo's belief that there is no anatomical relationship between the vagina and clitoris is contrasted by the general belief among researchers that vaginal orgasms are the result of clitoral stimulation; they maintain that clitoral tissue extends, or is at least likely stimulated by the clitoral bulbs, even in the area most commonly reported to be the G-spot.[7][9][31][49] "My view is that the G-spot is really just the extension of the clitoris on the inside of the vagina, analogous to the base of the male penis", said researcher Amichai Kilchevsky. Because female fetal development is the "default" direction of fetal development in the absence of substantial exposure to male hormones and therefore the penis is essentially a clitoris enlarged by such hormones, Kilchevsky believes that there is no evolutionary reason why females would have two separate structures capable of producing orgasms and blames the porn industry and "G-spot promoters" for "encouraging the myth" of a distinct G-spot.[49]

The general difficulty of achieving vaginal orgasms, which is a predicament that is likely due to nature easing the process of childbearing by drastically reducing the number of vaginal nerve endings,[1][4][45] challenge arguments that vaginal orgasms help encourage sexual intercourse in order to facilitate reproduction.[7][26] O'Connell stated that focusing on the G-spot to the exclusion of the rest of a woman's body is "a bit like stimulating a guy's testicles without touching the penis and expecting an orgasm to occur just because love is present". She stated that it "is best to think of the clitoris, urethra, and vagina as one unit because they are intimately related".[50] Ian Kerner stated that the G-spot may be "nothing more than the roots of the clitoris crisscrossing the urethral sponge".[50]

A Rutgers University study, published in 2011, was the first to map the female genitals onto the sensory portion of the brain, and supports the possibility of a distinct G-spot. When the research team asked several women to stimulate themselves in a functional magnetic resonance (fMRI) machine, brain scans showed stimulating the clitoris, vagina and cervix lit up distinct areas of the women's sensory cortex, which means the brain registered distinct feelings between stimulating the clitoris, the cervix and the vaginal wall – where the G-spot is reported to be.[29][51][52] "I think that the bulk of the evidence shows that the G-spot is not a particular thing," stated Barry Komisaruk, head of the research findings. "It's not like saying, 'What is the thyroid gland?' The G-spot is more of a thing like New York City is a thing. It's a region, it's a convergence of many different structures".[7]

In 2009, The Journal of Sexual Medicine held a debate for both sides of the G-spot issue, concluding that further evidence is needed to validate the existence of the G-spot.[5] In 2012, scholars Kilchevsky, Vardi, Lowenstein and Gruenwald stated in the journal, "Reports in the public media would lead one to believe the G-spot is a well-characterized entity capable of providing extreme sexual stimulation, yet this is far from the truth". The authors cited that dozens of trials have attempted to confirm the existence of a G-spot using surveys, pathologic specimens, various imaging modalities, and biochemical markers, and concluded:

The surveys found that a majority of women believe a G-spot actually exists, although not all of the women who believed in it were able to locate it. Attempts to characterize vaginal innervation have shown some differences in nerve distribution across the vagina, although the findings have not proven to be universally reproducible. Furthermore, radiographic studies have been unable to demonstrate a unique entity, other than the clitoris, whose direct stimulation leads to vaginal orgasm. Objective measures have failed to provide strong and consistent evidence for the existence of an anatomical site that could be related to the famed G-spot. However, reliable reports and anecdotal testimonials of the existence of a highly sensitive area in the distal anterior vaginal wall raise the question of whether enough investigative modalities have been implemented in the search of the G-spot.[7]

A 2014 review from Nature Reviews Urology reported that "no single structure consistent with a distinct G-spot has been identified".[53]

History

The release of fluids had been seen by medical practitioners as beneficial to health. Within this context, various methods were used over the centuries to release "female seed" (via vaginal lubrication or female ejaculation) as a treatment for suffocation ex semine retento (suffocation of the womb), female hysteria or green sickness. Methods included a midwife rubbing the walls of the vagina or insertion of the penis or penis-shaped objects into the vagina.[54] In the book History of V, Catherine Blackledge lists old terms for what she believes refer to the female prostate (the Skene's gland), including the little stream, the black pearl and palace of yin in China, the skin of the earthworm in Japan, and saspanda nadi in the India sex manual Ananga Ranga.[55]

The 17th-century Dutch physician Regnier de Graaf described female ejaculation and referred to an erogenous zone in the vagina that he linked as homologous with the male prostate; this zone was later reported by the German gynecologist Ernst Gräfenberg.[56] Coinage of the term G-spot has been credited to Addiego et al. in 1981, named after Gräfenberg,[57] and to Alice Kahn Ladas and Beverly Whipple et al. in 1982.[21] Gräfenberg's 1940s research, however, was dedicated to urethral stimulation; Gräfenberg stated, "An erotic zone always could be demonstrated on the anterior wall of the vagina along the course of the urethra".[58] The concept of the G-spot entered popular culture with the 1982 publication of The G Spot and Other Recent Discoveries About Human Sexuality by Ladas, Whipple and Perry,[21] but it was criticized immediately by gynecologists:[2][59] some of them denied its existence as the absence of arousal made it less likely to observe, and autopsy studies did not report it.[2]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d See page 135 Archived 2020-12-10 at the Wayback Machine for prostate information, and page 76 Archived 2020-12-10 at the Wayback Machine for G-spot and vaginal nerve ending information. Rosenthal, Martha (2012). Human Sexuality: From Cells to Society. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0618755714. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Morris, Desmond (2004). The Naked Woman: A Study of the Female Body. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. pp. 211–212. ISBN 978-0-312-33852-7.

- ^ Diane Tomalty, Olivia Giovannetti et al.: Should We Call It a Prostate? A Review of the Female Periurethral Glandular Tissue Morphology, Histochemistry, Nomenclature, and Role in Iatrogenic Sexual Dysfunction. In: Sexual Medicine Reviews. Volume 10, Issue 2, April 2022, page 183–194.

- ^ a b c d e f Balon, Richard; Segraves, Robert Taylor (2009). Clinical Manual of Sexual Disorders. American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 258. ISBN 978-1585629053. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Greenberg, Jerrold S.; Bruess, Clint E.; Oswalt, Sara B. (2014). Exploring the Dimensions of Human Sexuality. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 102–104. ISBN 978-1449648510. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Hines T (August 2001). "The G-Spot: A modern gynecologic myth". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 185 (2): 359–62. doi:10.1067/mob.2001.115995. PMID 11518892. S2CID 32381437.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kilchevsky, A; Vardi, Y; Lowenstein, L; Gruenwald, I (January 2012). "Is the Female G-Spot Truly a Distinct Anatomic Entity?". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 9 (3): 719–26. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02623.x. PMID 22240236.

- "G-Spot Does Not Exist, 'Without A Doubt,' Say Researchers". The Huffington Post. January 19, 2012.

- ^ a b c O'Connell, H. E.; Sanjeevan, K. V.; Hutson, J. M. (October 2005). "Anatomy of the clitoris". The Journal of Urology. 174 (4 Pt 1): 1189–95. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000173639.38898.cd. PMID 16145367. S2CID 26109805.

- Sharon Mascall (June 11, 2006). "Time for rethink on the clitoris". BBC News.

- ^ a b c Sex and Society, Volume 2. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. 2009. p. 590. ISBN 9780761479079. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ a b c d See page 98 Archived 2020-12-10 at the Wayback Machine for the 2009 King's College London's findings on the G-spot and page 145 Archived 2016-05-09 at the Wayback Machine for ultrasound/physiological material with regard to the G-spot. Ashton Acton (2012). Issues in Sexuality and Sexual Behavior Research: 2011 Edition. ScholarlyEditions. ISBN 978-1464966873. Archived from the original on July 17, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ a b c Buss, David M.; Meston, Cindy M. (2009). Why Women Have Sex: Understanding Sexual Motivations from Adventure to Revenge (and Everything in Between). Macmillan. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-1429955225. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ a b c Sloane, Ethel (2002). Biology of Women. Cengage Learning. p. 34. ISBN 9780766811423. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Crooks, Robert; Baur, Karla (2010). Our Sexuality. Cengage Learning. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-0495812944. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ Pfaus, J. G.; Quintana, G. R.; Mac Cionnaith, C.; Parada, M. (2016). "The whole versus the sum of some of the parts: Toward resolving the apparent controversy of clitoral versus vaginal orgasms". Socioaffective Neuroscience & Psychology. 6. Figure 4 b. doi:10.3402/snp.v6.32578. PMC 5084726. PMID 27791968.

- ^ Rosenthal, Martha (2012). Human Sexuality: From Cells to Society. Cengage Learning. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-0618755714. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ Kammerer-Doak, Dorothy; Rogers, Rebecca G. (June 2008). "Female Sexual Function and Dysfunction". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 35 (2): 169–183. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2008.03.006. PMID 18486835.

Most women report the inability to achieve orgasm with vaginal intercourse and require direct clitoral stimulation ... About 20% have coital climaxes...

- ^ Inari H. Hanel: Der G-Punkt in der Yoni-Massage Archived 2021-04-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Tristan Taormino (2009). The Big Book of Sex Toys. Quiver. pp. 100–101. ISBN 9781592333554. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ^ Addiego, F.; Belzer, E. G.; Comolli, J.; Moger, W.; Perry, J. D.; Whipple, B. (1981). "Female ejaculation: a case study". The Journal of Sex Research. 17 (1). Journal of Sex Research: 13–21. doi:10.1080/00224498109551094.

- ^ David H. Newman (2009). Hippocrates' Shadow. Simon & Schuster. p. 130. ISBN 978-1416551546. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ a b c William J. Taverner (2005). Taking Sides: Clashing Views On Controversial Issues In Human Sexuality. McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 79–82. ISBN 978-1429955225. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ Goldberg, DC; Whipple, B; Fishkin, RE; Waxman H; Fink PJ; Wiesberg M. (1983). "The Grafenberg Spot and female ejaculation: a review of initial hypotheses". J Sex Marital Ther. 9 (1): 27–37. doi:10.1080/00926238308405831. PMID 6686614.

- ^ Darling, CA; Davidson, JK; Conway-Welch, C. (1990). "Female ejaculation: perceived origins, the Grafenberg spot/area, and sexual responsiveness". Arch Sex Behav. 19 (1): 29–47. doi:10.1007/BF01541824. PMID 2327894. S2CID 25428390.

- ^ Federation of Feminist Women's Health Centers (1991). A New View of a Woman's Body. Feminist Health Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-9629945-0-0.

- ^ a b c Archer, John; Lloyd, Barbara (2002). Sex and Gender. Cambridge University Press. pp. 85–88. ISBN 9780521635332. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

- ^ a b Lloyd, Elisabeth Anne (2005). The Case Of The Female Orgasm: Bias In The Science Of Evolution. Harvard University Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780674017061. OCLC 432675780. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- ^ New Scientist. Vol. 197. New Science Publications (original from University of California). 2008. p. 6. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ New Scientist. New Science Publications (original from University of Virginia). 2008. p. 66. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ a b Pappas, Stephanie (April 9, 2012). "Does the Vaginal Orgasm Exist? Experts Debate". LiveScience. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ a b Buisson, Odile; Foldès, Pierre (2009). "The clitoral complex: a dynamic sonographic study". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 6 (5): 1223–31. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01231.x. PMID 19453931. S2CID 5096396.

- ^ a b Carroll, Janell L. (2013). Discovery Series: Human Sexuality (1st ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 103. ISBN 978-1111841898. Archived from the original on 2021-03-10. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ^ Lentz, Gretchen M; Lobo, Rogerio A.; Gershenson, David M; Katz, Vern L. (2012). Comprehensive Gynecology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 41. ISBN 978-0323091312. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ Komisaruk, Barry R.; Whipple, Beverly; Nasserzadeh, Sara; Beyer-Flores, Carlos (2009). The Orgasm Answer Guide. JHU Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-8018-9396-4. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ a b Bullough, Vern L.; Bullough, Bonnie (2014). Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 231. ISBN 978-1135825096. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- ^ Nicola Jones (3 July 2002). "Bigger is better when it comes to the G-Spot". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ a b Janice M. Irvine (2014). Disorders of Desire: Sexuality and Gender in Modern American Sexology. Temple University Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-1592131518. Archived from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ a b Rebecca Chalker (2011). The Clitoral Truth: The Secret World at Your Fingertips. Seven Stories Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-1609800109. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ Michael L. Krychman (2009). 100 Questions & Answers About Women's Sexual Wellness and Vitality: A Practical Guide for the Woman Seeking Sexual Fulfillment. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 98. ISBN 978-1449630775. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ Committee On Gynecologic Practice, American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists (September 2007). "ACOG Committee Opinion No. 378: Vaginal "rejuvenation" and cosmetic vaginal procedures". Obstet Gynecol. 110 (3): 737–8. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000263927.82639.9b. PMID 17766626.

- ^ Childs, Dan (2008-02-20). "G-Shot Parties: A Shot at Better Sex?". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2018-06-13. Retrieved 2010-01-17.

- ^ "BBC News - The G-spot 'doesn't appear to exist', say researchers". 2010-01-04. Archived from the original on 2017-11-29. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ "The real G-spot myth | Yvonne Roberts | Comment is free | guardian.co.uk". The Guardian. London. 2010-01-05. Archived from the original on 2018-06-13. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ Lois Rogers (January 3, 2010). "What an anti-climax: G-Spot is a myth - Times Online". The Times. London. Archived from the original on May 31, 2010. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ "BBC NEWS | Health | Female G spot 'can be detected'". html. 2008-02-20. Archived from the original on 2018-06-13. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ a b Weiten, Wayne; Dunn, Dana S.; Hammer, Elizabeth Yost (2011). Psychology Applied to Modern Life: Adjustment in the 21st Century. Cengage Learning. p. 386. ISBN 9781111186630. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ Santos, F; Taboga, S. (2003). "Female prostate: a review about biological repercussions of this gland in humans and rodents". Animal Reproduction. 3 (1): 3–18.

- ^ Babmindra, VP; Novozhilova, AP; Bragina, TA; et al. (1999). "The structural bases of the regulation of neuron sensitivity". Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 29 (6): 615–20. doi:10.1007/BF02462474. PMID 10651316. S2CID 9132976. Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ^ Vincenzo Puppo (September 2011). "Anatomy of the Clitoris: Revision and Clarifications about the Anatomical Terms for the Clitoris Proposed (without Scientific Bases) by Helen O'Connell, Emmanuele Jannini, and Odile Buisson". ISRN Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011 (ID 261464): 5. doi:10.5402/2011/261464. PMC 3175415. PMID 21941661.

- ^ a b Alexander, Brian (January 18, 2012). "Does the G-spot really exist? Scientist can't find it". MSNBC.com. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

- ^ a b Rob, Baedeker. "Sex: Fact and Fiction". WebMD. pp. 2–3. Archived from the original on January 12, 2014. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ Woodall, Camay (2014). Exploring the Essentials of Healthy Personality: What is Normal?. Vol. 2. ABC-CLIO. pp. 168–169. ISBN 978-1440831959. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ Komisaruk, B. R.; Wise, N.; Frangos, E.; Liu, W.-C.; Allen, K.; Brody, S. (2011). "Women's Clitoris, Vagina, and Cervix Mapped on the Sensory Cortex: fMRI Evidence". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 8 (10): 2822–30. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02388.x. PMC 3186818. PMID 21797981.

- Stephanie Pappas (August 5, 2011). "Surprise finding in response to nipple stimulation". CBS News.

- ^ Jannini, EA; Buisson, O; Rubio-Casillas, A (2014). "Beyond the G-spot: clitourethrovaginal complex anatomy in female orgasm". Nature Reviews Urology. 11 (9): 531–538. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2014.193. PMID 25112854. S2CID 13701675.

- ^ Blackledge, Catherine (2003). The Story of V: A Natural History of Female Sexuality. Rutgers University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-8135-3455-8.

history of v.

- ^ Blackledge, p. 201

- ^ Roeckelein, Jon E. (2006). Elsevier's Dictionary of Psychological Theories. Elsevier. p. 256. ISBN 9780444517500. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

The G-spot is not felt normally during a gynecological exam, because the area must be sexually stimulated in order for it to swell and be palpable; physicians, of course, do not sexually arouse their patients and, therefore, do not typically find the woman's G-spot.

- ^ Addiego, F; Belzer, EG; Comolli, J; Moger, W; Perry, JD; Whipple, B.]] (1981). "Female ejaculation: a case study". Journal of Sex Research. 17 (1): 13–21. doi:10.1080/00224498109551094.

- ^ Ernest Gräfenberg (1950). "The role of urethra in female orgasm". International Journal of Sexology. 3 (3): 145–148. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ^ "In Search of the Perfect G". Time. September 13, 1982. Archived from the original on May 24, 2007.