Cybersex trafficking

Cybersex trafficking, live streaming sexual abuse,[1][2][3] webcam sex tourism/abuse[4] or ICTs (Information and Communication Technologies)-facilitated sexual exploitation[5] is a cybercrime involving sex trafficking and the live streaming of coerced[6][7] sexual acts and/or rape on webcam.[8][9][10]

Cybersex trafficking is distinct from other sex crimes.[8] Victims are transported by traffickers to 'cybersex dens',[11][12][13] which are locations with webcams[14][9][15] and internet-connected devices with live streaming software. There, victims are forced to perform sexual acts[7] on themselves or other people[16] in sexual slavery[7][17] or raped by the traffickers or assisting assaulters in live videos. Victims are frequently ordered to watch the paying live distant consumers or purchasers on shared screens and follow their commands.[10][18][19] It is often a commercialized,[20] cyber form of forced prostitution.[7][21] Women,[22][23][24] children, and people in poverty are particularly vulnerable[10][15][25] to coerced internet sex. The computer-mediated communication images produced during the crime are a type of rape pornography[26] or child pornography[27][28][29] that is filmed and broadcast in real time and can be recorded.[30]

There is no data about the magnitude of cybersex trafficking in the world.[31][32][33] The technology to detect all incidents of the live streaming crime has not been developed yet.[34] Millions of reports of cybersex trafficking are sent to authorities annually.[35][failed verification] It is a billion-dollar, illicit industry[28] that was brought on with the Digital Age[9][25] and is connected to globalization. It has surged from the world-wide expansion of telecommunications and global proliferation of the internet[10] and smartphones,[36][37][38] particularly in developing countries. It has also been facilitated by the use of software, encrypted communication systems,[39] and network technologies[40] that are constantly evolving,[20] as well as the growth of international online payment systems with wire transfer services[36][32][41] and cryptocurrencies that hide the transactor's identities.[42][43]

The transnational nature and global scale of cybersex trafficking necessitate a united response by the nations, corporations, and organizations of the world to reduce incidents of the crime;[16] protect, rescue, and rehabilitate victims; and arrest and prosecute the perpetrators. Some governments have initiated advocacy and media campaigns that focus on awareness of the crime. They have also implemented training seminars held to teach law enforcement, prosecutors, and other authorities, as well as NGO workers, to combat the crime and provide trauma-informed aftercare service.[44] New legislation combating cybersex trafficking is needed in the twenty-first century.[45][38]

Terminology

[edit]Cyber-, as a combining form, is defined as 'connected with electronic communication networks, especially the internet.'[46] Sex trafficking is human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation, including sexual slavery.[47] Victims of cybersex trafficking are trafficked or transported to 'cybersex dens,' which are rooms or locations with a webcam.[14] The cybercrime also involves the transporting or streaming of images of the victims' bodies and sexual assaults in real time through a computer with a webcam to other computers connected to the internet.[8][6][10] It thus occurs partly in the physical or real world, as the sexual assault is real,[48] and partly in cyberspace.[49]

Victims

[edit]Victims, predominantly women[50][51][18] and children,[22] are abducted,[7] threatened, or deceived.[10][18] Others are drugged.[52] They are held captive and locked up[18] in rooms with covered or no windows and a webcam.[10] They experience physical and psychological trauma.[10][28][44] Gang rape has occurred on webcam.[17][53] Some are coerced into incest.[31] Victims have been denied food,[17] deprived of sleep,[18] and been forced to perform when sick.[6] They have contracted diseases, including tuberculosis, while in captivity.[6] A number are assaulted[6][18] or tortured.[29][54]

Victims can be exploited in any location where the cybersex traffickers have a computer, tablet, or phone with internet connection.[9] These locations, commonly referred to as 'cybersex dens,'[11][12][13] can be in homes, hotels, offices, internet cafes, and other businesses, making them extremely difficult or impossible for law enforcement to identify.[10] The number of cybersex trafficking victims is unknown.[31][32] Some victims are simultaneously forced into prostitution in a brothel or other location.[55]

Rescues involving live streaming commercial sexual exploitation of children by parents often require a separation of the minors from the families and new lives for them in a shelter.[44]

Some victims are not physically transported and held captive, but rather victims of online sextortion. They are threatened,[56] webcam blackmailed,[57] or bullied to film themselves committing online sexual acts.[58] Victims have been coerced to self-penetrate, in what has been called 'rape at a distance.'[57] Others are deceived, including by phony romantic partners who are really rape or child pornography distributors, to film themselves masturbating.[59] The videos are live streamed to purchasers or recorded for later sale.[30]

Those who are of a lower class, discriminate race, minority, or other social disadvantages are at an increased risk of being victimized.[40] The cybersex trafficking and or non-consensual dissemination of sexual content involving women and girls, often involving threats, have been referred to as "digital gender violence" or 'online gender-based violence.'[60]

Victims, despite being coerced, continue to be criminalized and prosecuted in certain jurisdictions.[40]

Perpetrators

[edit]Traffickers

[edit]Perpetrators who transport victims to locations with webcams and live streaming software. They or assisting assaulters then commit and film sex crimes to produce real time rape pornography or child pornography materials that may or may not be recorded. Male and female[41][61][62] perpetrators, operating behind a virtual barrier and often with anonymity, come from countries throughout the world[32][36][28] and from every social and economic class. Some traffickers and assaulters have been the victim's family members, friends, and acquaintances.[10][15][28] Traffickers can be part of or aided by international criminal organizations, local gangs, or small crime rings or just be one person.[10] They operate clandestinely and sometimes lack coordinated structures that can be eradicated by authorities.[10] The encrypted nature of modern technology makes it difficult to track perpetrators.[32] Some are motivated by sexual gratification.[29] Traffickers advertise children on the internet to obtain purchasers.[33] Funds acquired by cybersex traffickers can be laundered.[39]

Overseas predators seek out and pay for live streaming or made-to-order services[36] that sexually exploit children.[9][15][31] They engage in threats to gain the trust of local traffickers, often the victims' parents or neighbors, before the abuse takes place.[44]

Consumers

[edit]The online audience who are often from another country, may issue commands to the victims or rapists and pay for the services. The majority of purchasers or consumers are men,[54][28] as women who engage in cybersex prefer personal consensual cybersex in chat rooms or direct messaging.[63]

There is a strong correlation between viewing/purchasing child cybersex materials and actually sexually abusing children; cybersex materials can motivate cybersex consumers to move from the virtual world to committing sex crimes in person.[64]

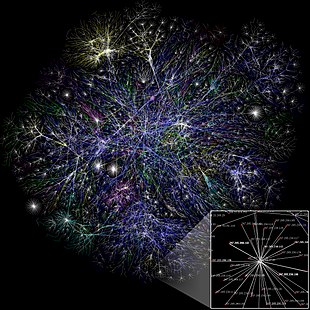

Internet platforms

[edit]

Cybersex trafficking is partly an internet-based crime.[17] Perpetrators use social media networks,[41] videoconferences, dating pages, online chat rooms, mobile apps,[48] dark web sites,[43][36] and other pages and domains.[65] They also use Telegram and other cloud-based instant messaging[57] and voice over IP services, as well as peer-to-peer (P2P) platforms, virtual private networks (VPN),[40] and Tor protocols and software, among other applications, to carry out activities anonymously.

Consumers have made payments to traffickers, who are sometimes the victim's family members, using Western Union, PayPal, and other electronic payment systems.[66]

Dark web

[edit]Cybersex trafficking occurs commonly on some dark websites,[43] where users are provided sophisticated technical cover against identification.[36]

Social media

[edit]Perpetrators use Facebook,[29][39][57] Instagram,[67] and other social media technologies.[36][41]

They use fake job listings in order to lure in victims.[68] They do this by creating fake job agencies to get victims to meet with the perpetrator.[69] These fake job listings can be things such as modeling gigs. Social media makes it easier for perpetrators to groom multiple people at once. They continuously send friend requests to increase their chances of getting a victim.[70] Social media gives perpetrators the platform to hide their identity. On social media, one can pretend to be anyone. Therefore, perpetrators use fake accounts to get victims attention. Most perpetrators pose as an attractive person who is living a lavish life.[69] This is used to attract vulnerable users who desire those luxuries. People who desperately desire a luxury living are the easiest targets. They fall for the manipulation that they too can live a life like ones depicted on fake accounts. Furthermore, younger people are more likely to be victims to cybersex on social media.[71] They are less aware and still learning how to use social media. In addition, adolescents are the more vulnerable on social media because they are exploring. Adolescents can use social media to explore their sexuality. This makes them more accessible to perpetrators.[72] Without guidance adolescents are at risk of falling for the tricks used to lure them into cybersex. In addition, they are less likely to detect when their security is at risk.[73] Perpetrators fake a romantic relationship with the victims on social media to exploit them.[74]

Perpetrators will convince victims to perform sexual acts. They can perform these sexual acts through tools such as webcams. More common on social media is to send pictures or videos. Victims send explicit pictures or videos because they trust the "friend" they have on social media. The victims will do it out of "love" or naiveness. Others do the performances out of fear. They can be threatened with information they previously shared with the perpetrator when they befriended them. However, it becomes an endless cycle when they perform the sexual acts once. After victims do these sexual acts, perpetrators use it as leverage. Perpetrators threaten them to do more sexual acts or they will share to their family and friends what they already have of them.[67]

Videotelephony

[edit]Cybersex trafficking occurs on Skype[75][37][36] and other videoconferencing applications.[76][32] Pedophiles direct child sex abuse using its live streaming services.[75][36][29]

Activities by region

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2020) |

Australia and Oceania

[edit]The Australian Federal Police (AFP) investigates cybersex trafficking crimes domestically and in the Asia-Pacific region.[38][75][32]

In 2016, Queensland Police Service officers from Task Force Argos In 2016, Queensland Police Service officers from Task Force Argos executed a federal search warrant at a 58-year-old Australian man's residence.[77] The Australian man pleaded guilty to numerous charges, including soliciting a child for sex and having sex with a child under 16 years of age outside of Australia.[78] Using Skype, the man conducted "live remote" sexual abuse, exploiting two young children in the Philippines while making payments to their mother.[77][78] The exploitation began when the children were only two and seven years old, and the abuse continued for nearly five years.[77] In May 2019, according to the Australian Federal Police (AFP), numerous cases were also uncovered related to Australians allegedly paying for and manipulating child sexual abuse.[79] In November 2019, Australia was alerted by Child Sexual Abuse live streaming when AUSTRAC filed legal action against Westpac Bank in relation to over 23 million suspected violations of the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 (Cth).[77]

Since 2017, IJM (International Justice Mission) Australia has been working on legal reforms to strengthen Australia's response to OSEC, commonly known as online sex trafficking of children.[80] On June 16, 2020, both houses of the Parliament of Australia enacted the Crimes Legislation Amendment (Sexual Crimes Against Children and Community Protection Measures) Bill 2019, which received royal assent on June 22, 2020.[80] Jacob Sarkodee, CEO of IJM Australia, noted that this new legislation recognizes the contribution of Australians to the growing demand for online sex trafficking of children.[80] According to 2020 Global OSEC report,[81] Australians are the third largest purchasers of cybersex trafficking of children in Philippines.[81][80] Under the proposal made by the IJM, the new legislation specifies that those who watch live streaming of child cybersex trafficking will receive the same penalties as those who manipulate and direct the sexual abuse of children themselves.[80]

East Asia

[edit]Cybersex trafficking occurred in the 2018–2020 Nth room case in South Korea.[82] In March 2020, South Korean news agencies reported some details about Nth room case: in crypto-messaging apps such as Telegram and Discord, "at least 74 women and 16 minors performed "sex shows" online for global audience of thousands who paid for cryptocurrency".[83] The victims were manipulated and tortured by viewers and were referred to as slaves. This case is related to the widespread availability and expansion of spy cameras (often referred to as "Molka") in South Korea.[citation needed]

North Korean women and girls have been subjected to penetrative vaginal and anal rape, groping, and forced masturbation in 'online rape dens' in China.[6][17][84]

In the trade for female North Koreans, cybersex trafficking is the small but rapidly growing element.[85] Girls as young as 9 years old were abused and exploited in "sex shows" that are broadcast live online to a paying audience, many of them are believed to be Korean men.[85][86]

According to Korea Future Initiative 2019, an estimated 60 percent of North Korean female refugees in China are trafficked into the sex trade,[85] of these, about 15 percent is sold into cybersex dens for exploitation by a global online audiences.[87] China's crackdown on undocumented North Koreans in July 2017 and a developing cybersex industry have fueled the rapid expansion of cybersex dens.[87]

Cybersex trafficking is thought to be extremely lucrative.[85] According to primary research, helpers experiences, and survivors testimonies, live streamed videos of cybersex featuring North Korean girls ages 9–14 can cost $60-$110, while videos featuring North Korean girls and women ages 17–24 can cost up to $90.[85] Offenders are believed to manipulate victims by the means of drugs and violence (physical and sexual).[87] In investigation conducted from February to September 2018, South Korean websites have been discovered to promote North Korean cybersex and pornography, even in the form of "pop-up" advertisements.[85] The high demand of North Korean cybersex victims is largely driven by South Korean man high involvement in searching Korean-language pornography.[87][85] In South Korea, compared to the penalties made for production and distribution of child sexual abuse imagery, the penalties for those who possess images of child porn are far below international standards.[88]

Europe

[edit]The European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (Europol) investigates and spreads awareness about live streaming sexual abuse.[43] Europol's European Cybercrime Centre (EC3) is especially equipped to combat the cybercrime.[20]

The United Kingdom's National Crime Agency (NCA) investigates cybersex trafficking crimes domestically and abroad.[38][36][32]

Europe was the second largest source of "online enticement" CyberTipline reports.[89] According to Global Threat Assessment 2018, many customers of Online Sexual Exploitation of Children (OSEC) are centered in Europe, along with those who are traffickers and victims of OSEC.[90]

In 2019, Europe accounted for 14% of all sexual exploitation worldwide.[91] Minors are usually trafficked for the purpose of sexual exploitation to EU, and most of them are foreign female children from Nigeria.[91] In Europe, women and children exploited in the sex trade are increasingly being advertised online, with children are found being promoted as adults.[91]

The great Internet freedom[92] and low web hosting costs[93] make the Netherlands one of the countries with a major market for online sexual exploitation.[94] In the 2018 annual report,Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) has said that about 79 percent (82803 out of 105047) of the URLs for materials of child sexual abuse are in Europe, with the vast majority of them are Netherlands-based.[95] The material is produced from different countries in the globe, but they are all hosted on computer servers in the Netherlands.[92] IWF has reported that over 105,047 URLs were linked to illegal images of child sexual abuse, with the Netherlands hosting 47 percent of the content.[93][95]

North America

[edit]The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)[38][27] and Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), the investigative arm of the United States Department of Homeland Security, carry out anti-cybersex trafficking operations.[61] The United States Department of State Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (J/TIP) partners with agencies and organization overseas to rescue cybersex trafficked victims.[96]

Southeast Asia

[edit]The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) identified the Philippines as the global center of cybersex trafficking.[11] The Office of Cybercrime within the Philippines Department of Justice receives hundreds of thousands of tips of videos and images of sexually exploited Filipino children on the internet.[11] The Philippine National Police, along with its Women and Children Protection Center (WCPC), Philippine Internet Crimes Against Child Center (PICACC),[32] Philippine InterAgency Council Against Trafficking (IACAT, Department of Justice (Philippines), and Department of Social Welfare and Development[96] fight cybersex trafficking in the country.[13][61] Rancho ni Cristo in Cebu is a shelter devoted exclusively to rehabilitating children of live streaming sexual abuse.[44] Children in the shelter are provided food, medical care, counseling, mentoring and life skills training.

The Royal Thai Police's Internet Crimes Against Children (TICAC) task force combats cybersex trafficking in the nation.[59]

Combating the crime

[edit]Authorities, skilled in online forensics, cryptography, and other areas,[32] use data analysis and information sharing to fight cybersex trafficking.[75] Deep learning, algorithms, and facial recognition are also hoped to combat the cybercrime.[39] Flagging or panic buttons on certain videoconferencing software enable users to report suspicious people or acts of live streaming sexual abuse.[30] Investigations are sometimes hindered by privacy laws that make it difficult to monitor and arrest perpetrators.[36]

The International Criminal Police Organization (ICPO-INTERPOL) collects evidence of live streaming sexual abuse and other sex crimes.[40] The Virtual Global Taskforce (VGT) comprises law enforcement agencies across the world who combat the cybercrime.[20] The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) funds training for police to identify and address the cybercrime.[16]

Multinational technology companies, such as Google, Microsoft, and Facebook, collaborate, develop digital tools, and assist law enforcement in combating it.[39]

Led by Thorn, an organization that uses technology to combat child sexual exploration globally, a coalition of Big Tech companies including Facebook, Microsoft, Google, and Twitter have been developing ever more sophisticated tools to put in the hands of law enforcement worldwide to combat this issue at every level.

Education

[edit]The Ministry of Education Malaysia introduced cybersex trafficking awareness in secondary school syllabuses.[97]

Research shows that predators under 18 years old use coercion and threats to conceal abuse, but adult predators use psychological abuse. Adult predators use psychological abuse to trick the child into thinking that they actually consented to having sex with them or that the child is responsible for what happened to them.[98]

Teaching the risks of online chatting to children is important to reduce the risk of being a victim of cybersex. With online chatting, a predator might gain knowledge on what a child's hobbies and favorite items are by stalking their page or waiting to see what a child posts. After a predator gains this personal knowledge, he goes on to speak to this child, pretending to also be a child with the same interests to lure them in after gaining their trust. This plays a risk because the child may never really know who's on the other side of the screen and potentially become a victim of a predator.[99]

Relation to other sex crimes

[edit]

Cybersex trafficking shares similar characteristics or overlaps with other sex crimes. That said, according to attorney Joshua T. Carback, it is "a unique development in the history of sexual violence"[8] and "distinct in several respects from traditional conceptions of online child pornography and human trafficking".[8] The main particularization is that involves victims being trafficked or transported and then raped or abused in live webcam sex shows.[8][100][41] The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime identified the cybercrime involving trafficked victims on webcam sex shows as an emerging problem.[101] The illegal live streaming shows occur in 'cybersex dens,' which are rooms equipped with webcams.[14] The cybercrime has sometimes been informally called 'webcam rape'.[102][103]

Non-governmental organizations

[edit]The International Justice Mission is one of the world's leading nonprofit organizations that carries out anti-cybersex trafficking initiatives.[25][15][10] End Child Prostitution, Child Pornography and Trafficking of Children for Sexual Purposes (ECPAT)[10][43] and the Peace and Integrity of Creation-Integrated Development Center Inc., a non-profit organization in the Philippine, support law enforcement operations against cybersex trafficking.[96]

The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children in the United States assists authorities in cybersex trafficking cases.[104] It provides CyberTipline reports to law enforcement agencies.[105]

Terre des hommes is an international non-profit that combats the live streaming sexual abuse of children.[36][28]

The Korea Future Initiative is a London-based organization that obtains evidence and publicizes violations of human rights, including the cybersex trafficking of North Korean women and girls in China.[51]

See also

[edit]- List of organizations that combat human trafficking

- Child pornography

- Hurtcore

- Livestreamed crime

- Andrew Tate

References

[edit]- ^ Brown, Rick; Napier, Sarah; Smith, Russell G (2020), Australians who view live streaming of child sexual abuse: An analysis of financial transactions, Australian Institute of Criminology, ISBN 9781925304336 pp. 1–4.

- ^ "Child Sex Abuse Livestreams Increase During Coronavirus Lockdowns". NPR. April 8, 2020.

- ^ "Philippines child slavery survivors fight to heal scars of abuse". Reuters. April 8, 2020.

- ^ Masri, Lena (December 31, 2015). "Webcam Child Sex Abuse". Capstones.

- ^ "Improving the regulation of cybersex trafficking of women and children through the use of data science and artificial intelligence" (PDF). Global Campus of Human Rights. October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "After Fleeing North Korea, Women Get Trapped as Cybersex Slaves in China". The New York Times. September 13, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "North Korean women 'forced into sex slavery' in China – report". BBC News. May 20, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Carback, Joshua T. (2018). "Cybersex Trafficking: Toward a More Effective Prosecutorial Response". Criminal Law Bulletin. 54 (1): 64–183.

- ^ a b c d e "Cybersex Trafficking". IJM. 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Cyber-sex trafficking: A 21st century scourge". CNN. July 18, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Senator warns of possible surge in child cybersex traffic". The Philippine Star. April 13, 2020.

- ^ a b "Duterte's drug war and child cybersex trafficking". The ASEAN Post. October 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Norwegian national, partner nabbed; 4 rescued from cybersex den". Manila Bulletin. May 1, 2020. Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ a b c "International Efforts by Police Leadership to Combat Human Trafficking". FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. June 8, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Child sex abuse live streams rising at 'alarming rate' amid surge in 'cybersex trafficking'". The Independent. November 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Safe from harm: Tackling online child sexual abuse in the Philippines". UNICEF Blogs. June 7, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Nicola; Farmer, Ben (May 20, 2019). "Oppressed, enslaved and brutalised: The women trafficked from North Korea into China's sex trade". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "These North Korean defectors were sold into China as cybersex slaves. Then they escaped". CNN. June 10, 2019.

- ^ "Man jailed in Sweden for ordering webcam rape in Philippines". The Telegraph. January 10, 2013. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Child Sexual Exploitation". Europol. 2020.

- ^ Greiman, Virginia & Bain, Christina (2013). "The Emergence of Cyber Activity as a Gateway to Human Trafficking". Journal of Information Warfare. 12 (2): 41–49. p. 43.

- ^ a b "Police rescue 4 women, child from Dumaguete cybersex den". Cebu Daily News. April 30, 2020.

- ^ "Australian arrested over alleged cybersex den". ABC News. April 19, 2013.

- ^ "In cybersex den: Dutchman nabbed, 8 women rescued". The Freeman. August 9, 2013.

- ^ a b c "IJM Seeks to End Cybersex Trafficking of Children and #RestartFreedom this Cyber Monday and Giving Tuesday". PR Newswire. November 28, 2016.

- ^ "National Cyber Crime Reporting Portal". India India. 2020. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2020.

- ^ a b "Philippines Makes More Child Cybersex Crime Arrests, Rescues". VOA. May 12, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Philippine children exploited in billion-dollar webcam paedophilia industry". The Sydney Morning Herald. July 8, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "First paedophile in NSW charged with cybersex trafficking". the Daily Telegraph. March 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Study on the Effects of New Information Technologies on the Abuse and Exploitation of Children" (PDF). UNODC. 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Philippines targets cybersex trafficking but young victims are often left in limbo". South China Morning Post. May 6, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Global taskforce tackles cybersex child trafficking in the Philippines". Reuters. April 15, 2019.

- ^ a b "Surge in online sex trade of children challenges anti-slavery campaigners". Reuters. December 1, 2016.

- ^ "Internet child sex abuse contagion in PH: 8 out of 10 perpetrators related to victims". Inquirer. May 21, 2020.

- ^ "1st Session, 42nd Parliament, Volume 150, Issue 194". Senate of Canada. April 18, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Cheap tech and widespread internet access fuel rise in cybersex trafficking". NBC News. June 30, 2018.

- ^ a b "Former UK army officer jailed for online child sex abuse". Reuters. May 22, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Cybersex trafficking spreads across Southeast Asia, fuelled by internet boom. And the law lags behind". South China Morning Post. September 11, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Chasing Shadows: Can technology save the slaves it snared?". Thomson Reuters Foundation. June 17, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "No country is free from child sexual abuse, exploitation, UN's top rights forum hears". UN News. March 3, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Webcam slavery: tech turns Filipino families into cybersex child traffickers". Reuters. June 17, 2018.

- ^ "How the internet fuels sexual exploitation and forced labour in Asia". South China Morning Post. May 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Online child sex abuse rises with COVID-19 lockdowns: Europol". Reuters. May 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "'We didn't have much to eat': Poverty pushes some kids towards paid sex abuse in the Philippines". CNA. July 9, 2019.

- ^ Dushi, Desara (October 10, 2019), "Chapter 12: Combating the Live-Streaming of Child Sexual Abuse and Sexual Exploitation: A Need for New Legislation", in Hunsinger, Jeremy; Allen, Matthew M.; Klastrup, Lisbeth (eds.), Second International Handbook of Internet Research, Springer, pp. 201–223, ISBN 978-9402415537 pp. 201-203.

- ^ "cyber- combining form". Oxford Learners Dictionaries. 2020.

- ^ Kara, Siddharth (2009). Sex Trafficking: Inside the Business of Modern Slavery. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231139618.

- ^ a b "Children at risk of increased online sexual exploitation – Andrew Bevan". The Scotsman. May 29, 2020.

- ^ "Philippine court convicts American of online child abuse". WILX NBC. May 27, 2020.

- ^ "Sri Lankan made Filipina wife 'cybersex slave' and molested stepdaughter". PLN. July 12, 2019.

- ^ a b "China: Thousands of North Korean women forced into prostitution: report". Deutsche Welle. May 20, 2019.

- ^ "Drugged Pinays paid P300 for cybersex". Journal Online (Philippines). May 2, 2020. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ "Attackers broadcast woman's horrific gang rape on Facebook Live as webcam shows the moment police arrived to save the victim". The New Zealand Herald. January 24, 2017.

- ^ a b "Why Are Australian Telcos and ISPs Enabling a Child Sexual Abuse Pandemic?". ABC. July 6, 2017.

- ^ "8 kids rescued from cybersex den in Taguig". Rappler. June 11, 2015.

- ^ "Swedish man convicted over 'online rape' of teens groomed into performing webcam sex acts". The Independent. December 1, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Five years in jail for "rape at a distance" for online abuser". The Brussels Times. September 26, 2018.

- ^ "Nepal Failing to Protect Women from Online Abuse". Human Rights Watch. May 18, 2020.

- ^ a b "Thai police say cybersex traffickers targeting boys from wealthy families". Reuters. June 17, 2019.

- ^ "Lawmakers vow to thwart 'digital gender violence'". Taipei Times. May 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c "'Trapped with abusers,' 7 kids rescued from sex trafficker in Luzon". Rappler. April 25, 2020.

- ^ "Australia urged to punish child cybersex offenders watching Filipino abuse". The Sydney Morning Herlad. July 14, 2017.

- ^ Schneider, Jennifer P. (2000). "A Qualitative Study of Cybersex Participants: Gender Differences, Recovery Issues, and Implications for Therapists". Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 7 (4): 249–278. doi:10.1080/10720160008403700. ISSN 1072-0162. S2CID 145698198.

- ^ Buschman, Jos; Wilcox, Dan; Krapohl, Donald; Oelrich, Marty; Hackett, Simon (2010). "Cybersex offender risk assessment. An explorative study". Journal of Sexual Aggression. 16 (2): 197–209. doi:10.1080/13552601003690518. ISSN 1355-2600. S2CID 145780130.

- ^ "Senate to probe rise in child cybersex trafficking". The Philippine Star. November 11, 2019.

- ^ "Federal Way man gets nearly 20 years in prison for directing child rape over Internet". Q13 Fox News. August 3, 2015.

- ^ a b "Sextortion (webcam blackmail)". www.nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk. June 20, 2023. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2022.

- ^ "Traffickers use of the Internet" (PDF).

- ^ a b "The Offline Harm of the Online Human Sex Trafficking Industry" – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Social Media Based Traffickers on the Rise". December 29, 2016.

- ^ "The Relationship between Sextortion during COVID-19 and Pre-pandemic Intimate Partner Violence" (PDF).

- ^ Eleuteri, Stefano; Saladino, Valeria; Verrastro, Valeria (2017). "Identity, relationships, sexuality, and risky behaviors of adolescents in the context of social media". Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 32 (3–4): 354–365. doi:10.1080/14681994.2017.1397953. S2CID 149424592.

- ^ Fatokun, F B; Hamid, S; Norman, A; Fatokun, J O (December 1, 2019). "The Impact of Age, Gender, and Educational level on the Cybersecurity Behaviors of Tertiary Institution Students: An Empirical investigation on Malaysian Universities". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 1339 (1): 012098. Bibcode:2019JPhCS1339a2098F. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1339/1/012098.

- ^ Corral, Rubi A.; Hussein, Maryam; Zia, Mehmil. "Cyber-Trafficking in Mexico". The International Affairs Review. Archived from the original on July 24, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Australian cyber sex trafficking 'most dark and evil crime we are seeing'". ABC News. September 7, 2016.

- ^ "PHILIPPINES Even 2-month-old babies can be cybersex victims – watchdog". Rappler. June 29, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Rick; Napier, Sarah (February 19, 2020). Australians who view live streaming of child sexual abuse: An analysis of financial transactions. Australian Institute of Criminology. doi:10.52922/ti04336. ISBN 978-1-925304-33-6. S2CID 213463721.

- ^ a b Cormack, Lucy (June 15, 2019). "Convicted child sex offender behind bars again for illicit Skype relationship with Filipino children under the age of 12". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ Cormack, Lucy (June 15, 2019). "'Someday I will get found and locked up': Inside the global fight against online child sex abuse". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "MEDIA RELEASE: New Australian law to aid in global fight against the online sexual exploitation of children". IJM Australia. June 25, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ a b https://ijm.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Final_OSEC-Public-Summary_05_20_2020.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "What is 'Nth Room' case and why it matters". Korea Herald. April 24, 2020.

- ^ "South Korea reels from latest high-tech, online sex trafficking case". The World from PRX. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "North Korean Women "Uniquely Vulnerable" to Sex Trafficking in China: Report". Radio Free Asia. May 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hee-soon, Yoon (2019). Sex Slaves: The Prostitution, Cybersex & Forced Marriage of North Korean Women & Girls in China (PDF). London: Korea Future Initiative. p. 12.

- ^ Sang-Hun, Choe (September 13, 2019). "After Fleeing North Korea, Women Get Trapped as Cybersex Slaves in China". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Engstran, Erin; Flynn, Caitlin; Harris, Meg (2020). "Gender and Migration from North Korea". Journal of Public & International Affairs.

- ^ Jeong, Andrew; Kim, Na-Young (November 30, 2019). "Global Child-Porn Sting Puts Pressure on South Korea to Toughen Laws". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ International Justice Mission with 14 Implementing and Advisory Partners. (2020, May). Full Length Report: Online Sexual Exploitation of Children in the Philippines: Analysis and Recommendations for Governments, Industry, and Civil Society. International Justice Mission.

- ^ "Global Threat Assessment 2018: Working Together to End Sexual Exploitation of Children Online" (PDF). WePROTECT Global Alliance. 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c Bondi, Hannah (January 18, 2019). "Trafficked Women and Girls Sold Online". Young Feminist Europe. Archived from the original on January 28, 2019. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Gibbons, Katie (April 27, 2020). "71% of child sex abuse images are from Netherlands". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ a b "Netherlands 'hosts most child sex abuse images'". BBC News. April 23, 2019. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ Vienna (2020). Leveraging innovation to fight trafficking in human beings: A comprehensive analysis of technology tools. © 2020 OSCE/Office of the Special Representative and Co-ordinator for Combating Trafficking in Human Beings. OCLC 1194979832.

- ^ a b "2018 Annual Report". IWF. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ a b c "12 minors rescue in Butuan City cybersex den". SunStar. May 22, 2020. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ "Teo: Cybersex and human trafficking now part of school syllabus". The Star. October 2, 2019.

- ^ Dombrowski, Stefan C.; LeMasney, John W.; Ahia, C. Emmanuel; Dickson, Shannon A. (February 2004). "Protecting Children From Online Sexual Predators: Technological, Psychoeducational, and Legal Considerations". Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 35 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.35.1.65. ISSN 1939-1323. S2CID 144588913.

- ^ von Weiler, Julia; Haardt-Becker, Annette; Schulte, Simone (July 2010). "Care and treatment of child victims of child pornographic exploitation (CPE) in Germany". Journal of Sexual Aggression. 16 (2): 211–222. doi:10.1080/13552601003759990. ISSN 1355-2600. S2CID 144923379.

- ^ "Webcam child sex: why Filipino families are coercing children to perform cybersex". South china Morning Post. June 26, 2018.

- ^ "Thailand Toughens Rape Laws". VOA News. June 1, 2019.

- ^ "Swedish Court to issue verdict on the Filipino 'webcam rape'". ScandAsia. January 10, 2013.

- ^ "Sunderland paedophile jailed for US webcam 'rape'". The Northern Echo. July 31, 2009.

- ^ "Sheriff's investigator: Children increasingly victims of cyber sex trafficking". The Augusta Chronicle. February 28, 2020.

- ^ "Online sexual exploitation of children in PH tripled in 3 years – study". Rappler. May 21, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Brown, Rick; Napier, Sarah; Smith, Russell G. (February 2, 2020). Australians who view live streaming of child sexual abuse: An analysis of financial transactions. Australian Institute of Criminology. ISBN 9781925304336.

- Bryce, Jo (November 3, 2009). "Chapter 16: Online sexual exploitation of children and young people". In Jewkes, Yvonne; Yar, Majid (eds.). Handbook of Internet Crime. Routledge. pp. 320–342. ISBN 978-1843925248.

- Carback, Joshua T. (2018). "Cybersex Trafficking: Toward a More Effective Prosecutorial Response". Criminal Law Bulletin. 54 (1): 64–183. Abstract.

- Chibba, Michael (April 2014). "Contemporary issues on human trafficking, migration and exploitation". Migration and Development. 3 (2): 163–173. doi:10.1080/21632324.2014.885286. S2CID 153982821. Abstract.

- Dushi, Desara (October 10, 2019). "Chapter 12: Combating the Live-Streaming of Child Sexual Abuse and Sexual Exploitation: A Need for New Legislation". In Hunsinger, Jeremy; Allen, Matthew M.; Klastrup, Lisbeth (eds.). Second International Handbook of Internet Research. Springer. pp. 201–223. ISBN 978-9402415537.

- Greiman, Virginia & Bain, Christina (2013). "The Emergence of Cyber Activity as a Gateway to Human Trafficking". Journal of Information Warfare. 12 (2): 41–49. Abstract.

- Humphreys, Krystal; Le Clair, Brian & Hicks, Janet (2019). "Intersections between Pornography and Human Trafficking: Training Ideas and Implications". Journal of Counselor Practice. 10 (1): 19–39.

- Reed, T.V. (June 6, 2014). Digitized Lives: Culture, Power, and Social Change in the Internet Era. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415819312.

- "Study on the Effects of New Information Technologies on the Abuse and Exploitation of Children" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2015.

- Quayle, Ethel; Ribisl, Kurt M. (March 1, 2013). Understanding and preventing online sexual exploitation of children. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415689410.

External links

[edit]- International Justice Mission (IJM) Cybersex Trafficking Casework (in English)

- Korea Future Initiative Report (London, 2019) Sex Slaves: The Prostitution, Cybersex & Forced Marriage of North Korean Women & Girls in China (in English)

- The United Nations Correspondents Association (UNCA) Briefing on Combatting Cybersex Trafficking (in English)