The Four Feathers (1939 film)

| The Four Feathers | |

|---|---|

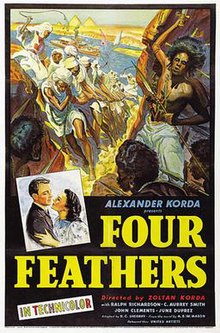

original 1939 movie poster | |

| Directed by | Zoltan Korda |

| Written by | R. C. Sherriff Lajos Bíró Arthur Wimperis |

| Based on | The Four Feathers 1902 novel by A.E.W. Mason |

| Produced by | Alexander Korda |

| Starring | John Clements June Duprez Ralph Richardson |

| Cinematography | Georges Perinal |

| Edited by | Henry Cornelius |

| Music by | Miklós Rózsa |

| Color process | Technicolor |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 130 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £216,275[1] or $1 million[2] or $300,000[3] £225,000 (UK)[4] |

| Box office | $1 million (rentals US)[3] |

The Four Feathers is a 1939 British Technicolor adventure film directed by Zoltan Korda, starring John Clements, Ralph Richardson, June Duprez, and C. Aubrey Smith. Set during the reign of Queen Victoria, it tells the story of a man accused of cowardice and his efforts to redeem his name. It is widely regarded as the best of the numerous film adaptations of the 1902 novel of the same name by A.E.W. Mason.

Plot

[edit]In 1895, the Royal North Surrey Regiment is called to active service to join the army of Sir Herbert Kitchener in the Mahdist War against the forces of the Khalifa. Forced into an army career by family tradition and fearful he might prove a coward in battle, Lieutenant Harry Faversham resigns his commission on the eve of its departure. As a result, his three friends and fellow officers, Captain John Durrance and Lieutenants Burroughs and Willoughby, show their contempt by each sending him a white feather—signifying cowardice—attached to a calling card. When his fiancée, Ethne Burroughs, says nothing in his defence, he bitterly demands a fourth from her. She refuses, but he plucks one from her fan.

Harry confides in an old mentor and former surgeon in his father's regiment, Dr. Sutton, that he now realises he did act out of cowardice and must attempt to redeem himself. He departs for Egypt. There, he disguises himself as a despised mute Sangali native, with the help of Dr. Harraz, to hide his lack of knowledge of the local languages.

During the army's advance, Durrance is ordered to take his company into the desert to lure the Khalifa's army away from the Nile so that Kitchener's army can sail past. Durrance is blinded by sunstroke, but hides it from his men. When the company is overrun, he is left for dead, while Burroughs and Willoughby are captured. Faversham takes the delirious Durrance across the desert and down the Nile to the vicinity of a British fort. As he is putting something into Durrance's wallet, Faversham is spotted and mistaken for a robber. He is placed in a convict gang, but escapes.

Six months later, the blind Durrance has returned to England. Out of pity, Ethne agrees to marry him. At dinner with Ethne, her father, and Dr. Sutton, Durrance relates the tale of his miraculous rescue. He pulls out a keepsake letter from Ethne, the only thing he had in his wallet during the "robbery". A white feather and his card drop out, revealing to the others that his rescuer was Faversham. Nobody has the heart to tell him.

Burroughs and Willoughby are thrown into a dungeon in Omdurman with other enemies of the Khalifa. Still playing the addled Sangali, Faversham surreptitiously gives them hope of escape and passes them a file, but arouses the suspicions of the guards. He is flogged and imprisoned with the others. He reveals his identity to his friends and organizes an escape during Kitchener's attack. Faversham leads the other prisoners in overpowering their guards and seizing the Khalifa's arsenal, which they hold until the arrival of Kitchener's forces.

Durrance learns of Faversham's deeds from a newspaper account and realises who saved him. He dictates a letter to Ethne, releasing her from their engagement on the fake pretext of going to Germany for a prolonged course of treatment to restore his eyesight. Later, Harry attends a dinner with his friends and Ethne. Ethne asks him what act of bravery will make her take back her feather. Faversham interrupts General Burroughs, Ethne's father, in the midst of his favourite war story about the Battle of Balaclava and corrects his embellishments (Faversham's father was there too); the general complains that he will never be able to tell that story again.

Cast

[edit]- John Clements as Harry Faversham

- Ralph Richardson as Captain John Durrance

- C. Aubrey Smith as General Burroughs

- June Duprez as Ethne Burroughs

- Allan Jeayes as General Faversham

- Jack Allen as Lieutenant Thomas Willoughby

- Donald Gray as Peter Burroughs

- Frederick Culley as Dr Sutton

- Clive Baxter as Young Harry Faversham

- Robert Rendel as Colonel

- Archibald Batty as Adjutant

- Derek Elphinstone as Lieutenant Parker

- Hal Walters as Joe

- Norman Pierce as Sergeant Brown

- Henry Oscar as Dr. Harraz

- John Laurie as the Khalifa Abdullah

- Amid Taftazani as Karaga Pasha

Production

[edit]It was mostly filmed on location in the Sudan in Technicolor.[5]

Forty soldiers of the 1st Battalion, the East Surrey Regiment, were used in period uniforms for scenes in which they withstood the Dervish advance en masse.[6]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film earned £225,000 in the UK and $801,564 in the US and Canada.[7]

Critical

[edit]This version is widely considered the best of all the numerous film adaptations of the novel.[8][9][10] Critic Michael Sragow praises the "film's gritty magic", calling it "next to Lawrence of Arabia (1962), the most harrowingly beautiful of all desert spectaculars."[8] "They [the film crew] and the cast all do their jobs so well that the action becomes poetic."[8] The Time Out review cites its "superb Technicolor camerawork ... and solid performances all round."[10] It has a 100% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 10 reviews, and with an average rating of 7.9/10.[11]

It was one of the most popular films of the year in Britain.[12]

Nominations

[edit]The film was nominated for the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival and the Mussolini Cup at the Venice Film Festival.

Home media

[edit]It is available on DVD and Blu-ray from the Criterion Collection. It is also available on HBO Max.

See also

[edit]- Khartoum, a 1966 film dealing with the events leading up to General Gordon's death.

References

[edit]- ^ Chapman, Llewella. "'The highest salary ever paid to a human being': Creating a Database of Film Costs from the Bank of England". Journal of British cinema and television, 2022-10. Vol. 19, no. 4. Edinburgh University Press. p. 470-494 at 487.

- ^ "War Scar Palaver". Variety. 28 September 1938. p. 63.

- ^ a b "Steur, for Goldwyn, denies any action because of UA bonus split". Variety. 27 September 1939. p. 4. Retrieved 9 August 2024.

- ^ James Chapman ‘The Billings verdict’: Kine Weekly and the British Box Office, 1936–62' Journal of British Cinema and Television, Volume 20 Issue 2, Page 200-238, p 205

- ^ "The Four Feathers". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ Michael Langley. (1972). The East Surrey Regiment. Cooper. p. 80. Published Leo Cooper, London. 1972. ISBN 0-85052-114-9.

- ^ Chapman, Llewella. "'The highest salary ever paid to a human being': Creating a Database of Film Costs from the Bank of England". Journal of British cinema and television, 2022-10. Vol. 19, no. 4. Edinburgh University Press. p. 470-494 at 489.

- ^ a b c Michael Sragow (11 October 2011). "The Four Feathers: Breaking the British Square". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ Dennis Schwartz (5 August 2019). "Four Feathers, The". Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ a b "The Four Feathers". Time Out. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ "The Four Feathers (1939)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ Harper, Sue (1994). Picturing the past : the rise and fall of the British costume film. BFI Publishing. p. 28.

External links

[edit]- 1939 films

- Films based on The Four Feathers

- 1930s war adventure films

- 1930s color films

- British historical adventure films

- British war adventure films

- British epic films

- Films shot at Denham Film Studios

- Films scored by Miklós Rózsa

- Films directed by Zoltán Korda

- Films produced by Alexander Korda

- Films set in 1895

- Films set in 1898

- London Films films

- 1939 war films

- 1930s English-language films

- 1930s British films

- Films about the British Army

- Films based on works by A. E. W. Mason

- English-language action drama films

- English-language war adventure films